Brave, wise and stunningly beautiful, Esther and Judith have much in common. Both Jewish heroines live under foreign domination. Both risk their lives to save their people from oppression. One of the few differences between the two women is that Judith is openly pious and Esther is not. Indeed, God is not even mentioned in the Hebrew version of the Book of Esther. So why was the story of Esther included in the Hebrew Bible while the Book of Judith was left out?

The Book of Esther appears among those books of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) known as the Writings (Ketubim). It is considered canonical by Jews and Christians alike, although the Orthodox Church follows the version found in the Septuagint (a Greek translation of the Old Testament produced in Alexandria in the third to the first century B.C.E.) rather than the Hebrew text. The Roman Catholic Church includes the Hebrew version but appends to it additions to the story found only in the Greek Septuagint.

The book tells the story of a young Jewish orphan named Esther and her cousin and guardian Mordecai, who reside in the Persian capital of Susa. The Persian king Ahasuerus is searching for a new queen, his first wife, Vashti, having been deposed for disobedience. (Vashti refused the king’s commands to show off her physical charms to guests at a banquet.) The beautiful young virgins of the empire, including Esther, are brought to the palace harem, where they undergo a 12-month beautification program (six months with oil of myrrh, six with perfumes and cosmetics)a before being presented to the king. When at last Esther appears in court, she immediately wins Ahasuerus’s favor and is crowned queen. “The king loved Esther more than all the other women,” the text tells us (Esther 2:17). On her cousin Mordecai’s advice, Esther tells no one, not even her husband, that she is Jewish. Not long after the marriage, Mordecai, a royal courtier, overhears two palace guards plotting to kill the king and informs Esther. The king is saved.

Sometime later, Mordecai gets into a quarrel with the king’s second-in-command, Haman, for refusing to bow or do obeisance to Haman. Determined to get revenge on Mordecai, Haman arranges for the slaughter of all the Jews in the Persian empire. After casting lots (pur in ancient Babylonian) to determine the date, Haman requests that the king issue an edict permitting all Jews to be slaughtered on the date cast, the 13th of the month of Adar.

Once again, Mordecai approaches Esther, this time to ask her to use her influence with the king to save the Jews. At first reluctant, Esther explains to Mordecai that anyone who goes before the king unsummoned will be put to death. Mordecai insists that the threat to her people is real and she must act: “Do not imagine that you, of all the Jews, will escape with your life by being in the king’s palace…Who knows, perhaps you have attained to royal position for just such a crisis” (Esther 4:13–14). Finally, Esther agrees to help, exclaiming, “If I perish, I perish” (Esther 4:16).

Donning her finest apparel, Esther waits at the entrance to the king’s throne room. When Ahasuerus sees her, he is not angered, and extends to her his golden scepter. “What troubles you, Queen Esther?” the king asks. “And what is your request? Even to half the kingdom, it shall be granted you” (Esther 5:3).

Esther simply invites the king and Haman to a wine banquet. They accept. At the banquet, too, Esther remains silent about the impending destruction of the Jews. But she invites Ahasuerus and Haman to another banquet, where she will make her plea.

Later that night, the king reads in the old court records of how Mordecai once saved his life and decides to reward him. He asks Haman for advice: “What shall be done for the man whom the king wishes to honor?” (Esther 6:6). Haman assumes the king is referring to him and suggests that the honoree be paraded about Susa on the king’s horse. Little does he know that the king is really talking about his enemy, Mordecai. In the ensuing scene Haman is forced to bestow upon Mordecai the very honor he dreamed of for himself: Mordecai is arrayed in the king’s robes and mounted on the king’s horse, while Haman leads him through Susa proclaiming, “Thus shall it be done for the man whom the king wishes to honor!” (Esther 6:11).

In the evening, Haman and Ahasuerus attend Esther’s banquet, where she finally makes her request of the king: “Let my life be granted me as my wish, and my people as my request. For we have been sold, my people and I, to be destroyed, massacred, and exterminated” (Esther 7:3–4).

Enraged, the king demands, “Who is he and where is he who dared to do this?” (Esther 7:5). She replies, “The adversary and enemy is this evil Haman!” (Esther 7:6). The king orders Haman impaled and makes Mordecai his new chief counselor. He also issues a new proclamation that permits the Jews to “avenge themselves on their enemies” (Esther 8:13); within Susa, and throughout the provinces, the Jews fight and kill their enemies.

Through a series of skillful political maneuvers, Esther has brought about Haman’s downfall and saved the Jews. The book concludes with Mordecai charging all the Jews to commemorate these events each year with merrymaking during the festival of Purim, on the 14th and 15th of Adar.b

The Book of Judith, unlike the Book of Esther, is not part of the Jewish or Protestant canon. It appears instead in the Apocrypha, a group of books found only in the Greek Septuagint. These books are considered canonical by the Orthodox Church and deuterocanonical (belonging to the secondary canon) by the Roman Catholic Church.

Chronologically, the Book of Judith follows Esther. It was written later (in the mid-second century B.C.E.; whereas Esther was written in the late fourth or early third century B.C.E.) and the story is set later. In Judith, the Babylonian Exile has ended; the Jews have returned to Israel. But Israel, along with all the other nations of the eastern Mediterranean coast, is under attack for having refused to come to the aid of King Nebuchadnezzar of Assyria (not Babylonia!—more of this later) in putting down a rebellion. Holofernes, the chief general in the Assyrian army, has subdued the other nations of the Levant. The Jews alone have resisted, thanks in large part to the residents of the small town of Bethulia, in the hills somewhere outside Jerusalem. The Bethulians have barricaded the surrounding mountain passes so that the Assyrians cannot enter Jerusalem and desecrate the Temple. Achior, an Ammonite mercenary, informs Holofernes that he will never win unless the Israelites sin and their God turns away from them.

Holofernes is infuriated and commands that Achior be handed over to Bethulia so that he may be slain with the Jews. The Bethulians, however, welcome Achior among them. In response Holofernes’s army encamps beneath Bethulia and cuts off the town’s water supply. As the children of Bethulia become listless and the women and young men faint in the streets, the resolve of the people begins to crumble. They order their town magistrate, Uzziah, to surrender.

Enter Judith, a beautiful, wealthy widow who berates Uzziah and the town elders. “Do not try to bind the purposes of the Lord our God,” Judith tells them. “For God is not like a human being, to be threatened, or like a mere mortal, to be won over by pleading. Therefore, while we wait for his deliverance, let us call upon him to help us, and he will hear our voice, if it pleases him” (Judith 8:16–17). Judith promises her townspeople that she will save Israel from Holofernes, although she won’t tell them how. She simply instructs the town magistrate to let her sneak out the city gate that night.

That evening, bowing low and covering her head with ashes, Judith prays to God for his help and protection. She then removes her widow’s weeds, dresses to “astound the eyes of all the men who might see her” (Judith 10:4), and leaves Bethulia with her maid. She carries with her a bag of food so she needn’t eat with the enemy. When she meets enemy soldiers, she tells them she is fleeing the Hebrews.

Brought before Holofernes, Judith insists that the Hebrews are on the verge of sinning and thus of being destroyed by God. The Hebrews are in such want of food and water, Judith prevaricates, that they are planning to eat forbidden food and drink wine that had been devoted to the Temple.

Calling herself Holofernes’s slave, Judith promises to remain with the Assyrians. Each day, she will pray to find out when the Israelites will sin. Only then will she lead the Assyrians back to Bethulia, where they will triumph. The Assyrians succumb to Judith’s lies and invite her to stay.

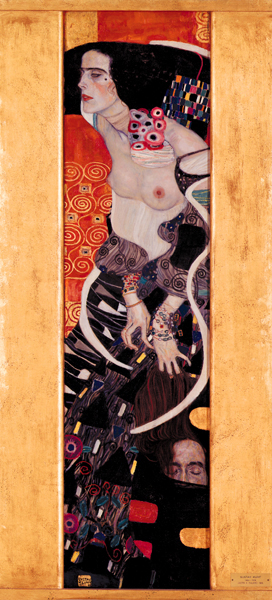

For three days, Judith remains in the camp, leaving only to purify herself in a spring and to pray each night. On the fourth night, Holofernes invites Judith to a banquet, where he hopes to seduce her. But Holofernes imbibes “much more than he had ever drunk in any one day since he was born” (Judith 12:20). When he passes out on the bed, Judith takes his sword from the bedpost, cries out “Give me strength today, O Lord, God of Israel” (Judith 13:7), and slices off his head. She returns in triumph to Bethulia, the head of Holofernes in her food bag.

The exultant Bethulians decimate the panicking enemy forces. The high priest of Jerusalem comes to thank Judith, who, like Miriam and Deborah before her, leads the women of Israel in a song of praise. The people of Bethulia travel to Jerusalem, where they spend three months feasting and sacrificing and giving thanks at the Temple. For the rest of her 105 years, Judith is celebrated as a great hero. She remains a widow, although, of course, “many desired to marry her” (Judith 16:22).

The similarities between the books of Esther and Judith are extensive, not the least of which being that, in both, a Jewish heroine uses her courage and resourcefulness to save her people from imminent destruction at the hands of gentiles.1

On the literary level, both books are Jewish novellas of historical fiction. Esther purports to be set in the Persian capital of Susa during the reign of Xerxes (Ahasuerus in Hebrew), who ruled from 486 to 465 B.C.E.c Although the character and events have not been corroborated in the historical record and in fact contradict what we do know of the reign of the historical Xerxes (for example, throughout his reign, he had one queen, named Amestris), the author’s subterfuge is so successful that debates about the historicity of Esther continue to this day.2 The fictional nature of Judith is much more apparent, since the book begins with a whopping historical blunder. The first verse identifies Nebuchadnezzar as the king of the Assyrians ruling from Nineveh after the Exile (Judith 1:1)! In fact, Nebuchadnezzar was a Babylonian emperor who ruled after the fall of the Assyrian empire and its capital, Nineveh. In 587 B.C.E., Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Jerusalem and its Temple and sent the Jews into exile. They would not be allowed to return until the Persians defeated Babylon in 539 B.C.E. The town of Bethulia is also an imagined place.

The structure of the two books is similar. As André LaCocque of the Chicago Theological Seminary points out, “The sequence [of both stories] is the same: life threat, deliverance, vengeance, triumph.”3 Both books contain lengthy introductory episodes involving rebellions. In Esther, Queen Vashti’s rebellion against the king sets in motion the whole story; Judith opens with an armed rebellion against King Nebuchadnezzar, which brings Holofernes to the Levant. The focus then narrows to the Jewish protagonists and their immediate associates. In both books the main conflict is resolved in a series of reversals, in which the victims become the victors and the ruled become the rulers.4 Each book’s main reversal occurs through the action of the heroine: Esther accuses Haman before the king, leading to his downfall and death (Esther 7:6); Judith beheads Holofernes (Judith 13:6–8).

At their introductions both Esther and Judith lead secluded lives; Esther in the royal harem and Judith in a tent on the roof of her dead husband’s house. Before leaving the relative security of these quarters to confront danger on behalf of the Jews, they perform beautification rituals. They are both charming, beautiful and seductive. They both achieve their ends at dinner parties, where they have plied the men with wine.

Because of Esther and Judith, the enemies of the Jews—Haman and 75,000 others in Esther, Holofernes and the Assyrian army in Judith—end up dead. At the end of both books, the Jews rejoice, with Esther and Judith playing leading roles at the celebrations. God never intervenes overtly in either book; both stories rely on the political acumen and bravery of their respective heroines.5

Both books rely heavily on humor and irony to convey their message. In Esther, Haman is forced to parade his enemy Mordecai through town. (The rabbis made the scene even more humiliating by adding the detail that Haman’s own daughter empties a chamber pot over her father’s head as he passes by!) Judith, being wined and dined in Holofernes’s tent as a prelude to seduction, makes a deeply ironic comment: “I will gladly drink, my lord, because today is the greatest day in my whole life” (Judith 12:18). Holofernes assumes she is referring to the prospect of having sex with him; we know she is actually referring to his imminent demise.

On the level of character, too, many parallels can be drawn. Esther is described as beautiful of face and figure (Esther 2:7), as is Judith (Judith 8:7). Esther is an orphan, Judith a widow; both are protected in Jewish society, but they are also marginalized through their lack of position in a family unit. This marginalized status, along with their secondary status as women in a patriarchal society, makes them role models for the Jewish community under alien domination.6

The sexuality of both characters is also prominent. Esther wins the king’s favor in what Michael Fox has characterized as a “sex contest.”7 Judith murders Holofernes after a banquet that is supposed to culminate in his sexual conquest of her. Both women use their appearance and sex appeal as weapons.

Both also have strong rhetorical skills. Esther’s speeches to Ahasuerus are masterpieces of a courtier’s skill, while Judith uses deceptive speech to lull Holofernes into a false sense of security. Before leaving for the Assyrian camp, Judith even prays that her lies will help her defeat the enemy: “Please, please God of my father…make my deceitful words bring wound and bruise on those who have planned cruel things against your covenant, and against your sacred house” (Judith 9:12–13; see also 9:10). In the Septuagint version of the Book of Esther, Esther also petitions God for “eloquent speech” before she appears before the king (Addition C, 14:13).

Many of the similarities between Esther and Judith have long been recognized. In the comments of the church fathers such as Clement of Rome, Clement of Alexandria, Athanasius of Alexandria and Augustine and in modern commentaries, the books of Esther and Judith are often grouped together, compared and contrasted. In the Septuagint, Judith immediately follows Esther. This pairing occurs even in the world of art, where we find that the same Renaissance painter, Artemesia Gentileschi, uses both women as subjects.

The similarities cannot be attributed to coincidence. Rather, the author of Judith clearly used Esther as a model.8 Yet, in defining what a great Jewish heroine should be (Judith’s name means “Jewess”), the author of Judith made some significant changes.

First, there are no equivalents to the characters of Vashti and Mordecai in the story of Judith. The contrast between Vashti’s disobedience and Esther’s obedience is critical to the portrayal of Esther. No female protagonist serves as a foil for Judith, however; Judith is unique.

Likewise, Mordecai is a unique character. As Esther’s guardian he at first controls her actions (“for Esther obeyed Mordecai just as when she was brought up by him,” Esther 2:20); Judith tells other people what to do. Mordecai sets the story in motion by refusing to obey Haman, which results in the danger to the Jews of Persia; the Jews of Bethulia, in contrast, put themselves in danger by refusing to capitulate in a war. Mordecai galvanizes Esther into action against Haman; Judith needs no urging from anyone. And finally, at the end of the Book of Esther, Mordecai becomes the king’s second-in-command; there is no equivalent in Judith.

Two other differences bear mentioning. The Book of Esther is set in Persia, in the Diaspora, and the concerns and interests of all the characters reside in the Diaspora. They display no interest in the biblical land of Israel or its institutions; the exile from Judah gets only a passing reference in Mordecai’s genealogy (Esther 2:6). Gentile rule is not a problem for the author of Esther as long as it is benevolent. Judith, however, is set in Israel (albeit in a fictional location), and displays a great interest in and concern for Jerusalem, the Temple and its institutions. The author of Judith envisions a Jewish community governed by a high priest from the Temple in Jerusalem. For the author of Judith, unlike the author of Esther, gentile rule is never benevolent and must be opposed.

The differences in geographical and political stance reflect the different dates of the books. Esther, written in the eastern Diaspora in the late fourth or early third centuries B.C.E., reflects the relatively benign rule of the Persians over their subject people. Foreigners could and did rise to prominence in the Persian court, as is witnessed in the Bible by Nehemiah, cupbearer to King Artaxerxes I (Nehemiah 1:11). Judith, however, was written around 150 B.C.E., the time of the Maccabean revolt. The Maccabees (also called the Hasmoneans) were a Jewish dynasty that successfully rose against their Greek Seleucid overlords in the 160s B.C.E. and founded, for the first time in 450 years, an independent Jewish state. They would rule until the Romans entered Judea in 63 B.C.E. For the Jewish author of Judith, writing during or immediately after the initial revolt, foreign rulers were the enemy.

The establishment of the Jewish festival of Purim in the Book of Esther also constitutes a major difference between the two books. The book’s raison d’être is the creation of this festival. As is stated in Esther 9:28, “These days should be remembered and kept throughout every generation, in every family, province and city; and these days of Purim should never fall into disuse among the Jews, nor should the commemoration of these days cease among their descendants.” In fact, Purim, since it was not a festival established by Moses in the Torah, did have trouble winning acceptance among all Jews. However, its popularity proved too strong in the end for it to be abolished.

The Book of Judith does not seek to establish a permanent festival, although the story of Judith, because of its connection with the Maccabean revolt, was later associated with the festival of Hanukkah, which commemorates this revolt. Hanukkah, too, was not established by Moses and therefore was not accepted by all Jews.

Most striking is the difference in the role that religion and piety play in the two stories. In the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible, God is never mentioned by name (a distinction shared with only one other biblical book, the Song of Songs).d Neither Esther nor Mordecai displays any concern for any of the laws of Judaism (Esther 3:8). They do not pray, make sacrifices or perform other acts of conventional religious piety.9 Instead Esther becomes the sexual partner and then the wife of a gentile; she lives in his palace and eats his food with no recognition of the laws of kashrut (Jewish dietary laws). Esther is apparently so assimilated that her husband Ahasuerus and his court have no idea that she is a Jew!

The Book of Judith remedies all the religious deficiencies of Hebrew Esther: God is central to the story, and Judith wears her piety openly. When she is first introduced, we learn that “no one…spoke ill of her, so devoutly did she fear God” (Judith 8:8). Throughout the book, the Law is observed, and Judith fasts, prays and offers sound theology to the leaders of Bethulia. When she ventures into the enemy camp, she apparently upholds the laws of kashrut by refusing all food from the gentile Holofernes and she undertakes a nightly purification ritual. Judith never has sexual intercourse with a gentile, or anyone else, for that matter, choosing to remain a widow for the rest of her life. At the end of the book, Judith dedicates all the spoil of Holofernes to the Temple (Judith 16:19). Clearly, the author of Judith has tried to create a more acceptable heroine for ancient Jewish society. Why, then, did the Book of Judith not become part of the Jewish canon?

Several reasons have been put forth for Judith’s exclusion.e One is the language: Although most scholars today agree that Judith was written in Hebrew and then translated into Greek, by the time the Jewish canon was being formed, the Hebrew original may have been no longer extant. Only Hebrew or Aramaic books became part of the Jewish canon; hence Greek Judith was excluded. (The language of the Septuagint was Greek, so Judith was included there.) Also, no books written later than the Persian period (538–332 B.C.E.)f were included in the Jewish canon; Judith was written in the second century B.C.E. (There was no such restriction for the Septuagint.) Other minor reasons for Judith’s exclusion include the book’s obvious historical errors; its support of the Hasmonean dynasty, which was out of favor with the rabbis; and its occasional deviation from rabbinic law (for example, Achior does not undergo the full rabbinic ritual of conversion after he arrives in Bethulia).

Esther’s ultimate acceptance into the Jewish canon is usually explained by the appeal of the story to a wide audience and the popularity of Purim. This seems to have been enough to overcome objections made in rabbinic circles in the first four centuries C.E. about the secular nature of the book and the non-Mosaic character of the festival of Purim.

I would like to suggest another reason why Esther was accepted and Judith was dropped without a fight: Esther always works within the system. Judith does not. The books of the Bible were written by men for men. Recent feminist scholarship has aimed to expose that reality and also to discover “between the lines” the voice of women from the biblical world. Esther has been a troubling figure for feminist critics, however. As Alice Laffey of Holy Cross College writes: “In contrast to Vashti, who refused to be men’s sexual object and her husband’s toy, Esther is the stereotypical woman in a man’s world.” Kristin de Troyer of Claremont Theological Seminary notes, “[The book of Esther] has a hidden agenda. Between the lines it transmits a code, a norm of behaviour for women. This code and the norm is delivered completely from the male point of view.”10 Although Esther acts with considerable skill and bravery to save the Jews from destruction, she leaves the patriarchal norms of ancient Jewish (and Persian) society intact.

First of all, Esther is married, as all young women should be. Her primary characteristic is her beauty, which only adds to the honor of the king who possesses her. She is also obedient. She respects the power of the man over his household. The importance of this is emphasized from the first chapter, in which Vashti defies Ahasuerus’s command to come before his guests during his banquet. So great is the threat that it must be countermanded by law: “All women will give honor to their husbands, high and low alike,” and “every man should be master in his own house” (Esther 1:20, 22).

Esther does not work publicly. She leaves the private quarters of the women only briefly; both her dinner parties take place in private. She herself does not slay Haman; Ahasuerus sentences him. When the king gives her Haman’s property, she turns its management over to Mordecai. She receives permission from the king to thwart the edict against the Jews, but it is Mordecai who writes the letters and gives the commands. As for the establishment of the festival of Purim, Mordecai writes the initial letter and Esther merely confirms it. Only one verse gives a hint that Esther actually exercises public power on her own: “The command of Queen Esther fixed those practices of Purim, and it was recorded in writing” (Esther 9:32). Finally, at the end of the book, Esther completely disappears, and all the adulation is reserved for Mordecai, “for he sought the good of his people and interceded for the welfare of all his descendants” (Esther 10:3).

How does Judith fare under the same scrutiny? According to Alice Bellis of Howard University, Judith is “perhaps the strongest Hebrew hero in all of biblical literature.”11 Unlike Esther, who allows the males around her to carry out the violence on her enemies, Judith herself wields the sword—a sword that belongs, not coincidentally, to a man.

This is not the only way in which Judith subverts her patriarchal society. She is introduced with her own genealogy, the longest of any woman in the Hebrew Bible. She is a rich, beautiful, presumably childless widow—all potential threats to the patriarchal order. Wealth is meant to be owned and controlled by men, as the Book of Esther demonstrates. Beauty is dangerous if not properly controlled, preferably through marriage. Widowhood was not a desirable state, especially for young women. There are other famous young biblical widows—Abigail, Bathsheba, Ruth—but they all remarry. Indeed Judith, as a young childless widow, is under an obligation to produce an heir for her deceased husband through the law of levirate marriage (her husband’s brother is required to marry her—Deuteronomy 25:5–10), but she shows no concern for this. Her husband has been dead for more than three years, and it seems she is enjoying her emancipated status!

Judith directly attacks her town leaders. She upbraids and orders about the elders and the town magistrate Uzziah, and then tells them that she will save the day.

In the all-male sphere of the enemy camp, Judith appears unprotected. Furthermore, she lies, albeit to Holofernes. In this, she can be compared to the “strange woman” of Proverbs, whose “seductive speech” leads men “like an ox to the slaughter” (Proverbs 7:21–23).

Even after the Assyrian threat has dissipated, Judith does not resubmit to the patriarchal norm. She remains a widow with control over her own inherited wealth. Several commentators, clearly disturbed by this, have tried to marry her off to Achior. But Judith will not be subsumed into the patriarchal order so easily. She is a dangerous woman, dangerous to men because she refuses to fulfill—and in fact subverts—the gender expectations of her society.

Why was the Book of Judith excluded when Esther, with all its theological problems, was included? Because Esther never threatened the status quo, but Judith was a dangerous woman who had the power to subvert Jewish society. Like Vashti before her, Judith had to go.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

According to Esther 9:15, the Jews in Susa had to fight a second day, Adar 14; therefore they rested and celebrated on Adar 15. Thus it became customary for Jews in walled cities like Susa to celebrate a second day. Even today in Jerusalem the festival lasts for two days.

See Michael Heltzer, “The Book of Esther: Where Does Fiction Start and History End?” BR 08:01; Carey A. Moore, “Eight Questions Most Frequently Asked About the Book of Esther,” BR 03:01; and Sidnie White Crawford, “Has Every Book of the Bible Been Found Among the Dead Sea Scrolls?” BR 12:05.

See Rachel B.K. Sabua, “The Hidden Hand of God,” BR 08:01.

For other theories, see Carey A. Moore, “Judith: The Case of the Pious Killer,” BR 06:01.

Endnotes

Unless otherwise noted, I am referring to the version of Esther found in the Hebrew Masoretic text, which is the text translated in most English Bibles.

See, for example, Timothy Laniak, Shame and Honor in the Book of Esther (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1998), who states: “I do not count myself among those who reject the Book of Esther as a source of history” (p. 3, n. 5).

André LaCocque, The Feminine Unconventional: Four Subversive Figures in Israel’s Tradition (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1990), p. 71.

See the excellent studies of Sandra Beth Berg, The Book of Esther (Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1979), and Toni Craven, Artistry and Faith in the Book of Judith (Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1983), on the literary structures of the two books.

This is not so in Septuagint Esther, where God intervenes to make the king sleepless (Addition D, 6:1) and causes the king to accept Esther when she appears unsummoned before him in the throne room (Addition D, 15:8).

See Sidnie Ann White, “Esther: A Feminine Model for Jewish Diaspora,” in Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel, ed. Peggy L. Day (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1989), pp. 161–177; and Carey Moore, Judith, Anchor Bible Series 40 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1985), p. 62.

Michael Fox, Character and Ideology in the Book of Esther (Columbia, SC: Univ. of South Carolina, 1991), p. 28.

I have argued elsewhere that another model for the author of Judith is the story of Jael and Deborah in Judges 4–5. Both Jael and Judith are heroines who kill an enemy of Israel single-handedly, with a blow to the head. In both cases God approves of their actions. There are erotic elements in both stories, and both men are killed when asleep, lulled into a false sense of security by the presence of the women. Both women display the bodies of the fallen warriors to male leaders (Barak, Uzziah and Achior). A triumphant hymn in praise of God and the women bring both stories to a close. For further comparison, see White, “In the Steps of Jael and Deborah: Judith as Heroine,” in No One Spoke Ill of Her, ed. James VanderKam (Atlanta: Scholars, 1992), pp. 5–16.

Mordecai does don ritual mourning garb when he hears Haman’s decree (Esther 4:1), and Esther orders all the Jews of Susa to fast for three days before she appears unsummoned before the king (Esther 4:15–16). However, the reason for the fast is unclear, and the purpose (to capture God’s attention?) is unspecified. I have argued elsewhere that there is an implied theology in Hebrew Esther which assumes a belief in God and God’s action in history, but the fact remains that this is only implied, not directly stated. See Sidnie White Crawford, “Esther,” in The New Interpreter’s Bible (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1999), vol. 3, pp. 866–870.

Alice Laffey, An Introduction to the Old Testament: A Feminist Perspective (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1988), p. 216; Esther Fuchs, “The Status and Role of Female Heroines in the Biblical Narrative,” in Women in the Hebrew Bible, ed. Alice Bach (New York/London: Routledge, 1999), p. 80; Kristin de Troyer, “An Oriental Beauty Parlour: An Analysis of Esther 2:8–18 in the Hebrew, the Septuagint and the Second Greek Text,” in A Feminist Companion to Esther, Judith and Susanna, ed. Athalya Brenner (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), p. 55.