Trude Dothan arrived at the Gaza checkpoint precisely at eight in the morning. She had left her Jerusalem flat before dawn, had driven westward down the umber Judean hills toward the coast, then headed south toward Ashkelon—3,000 years ago, a powerful city-state within the Philistine pentapolis—now, a thriving Israeli city. South of Ashkelon, there were fewer Israeli settlements to be seen, then none at all. Prof. Dothan approached the Gaza Strip with a mixture of trepidation and anticipation.

This was one appointment for which she did not want to be late. The military commander had said eight, and she was there on the dot. A convoy was awaiting her.

It was hardly a time to be wandering around the Gaza Strip looking for antiquities. In early 1968, less than a year after the Six Day War, Gaza was a hotbed of terrorism. Hand grenades were being lobbed through open car windows with disturbing regularity. No one was certain that all the Egyptian mine fields had been cleared. Non-resident Israeli civilians were barred from the Strip altogether.

An expert in ancient anthropoid coffins, Trude Dothan had studied them in the detached manner of a scholar. Now, as she passed through the Gaza checkpoint, she wondered to herself whether she might not end up buried in one prematurely.

The convoy was led by a heavy truck with mine-detecting equipment. The archaeologist and her colleagues followed, several vehicles behind, with rolled-up windows against grenade attacks, despite the increasing heat from the blazing Gaza sun. The convoy rumbled through Gaza city itself, past the Great Mosque which had been built by Crusaders as a church, re-using stones from earlier buildings, including an ancient synagogue. That is why a beautifully carved menorah can be seen in one of the columns of the Great Mosque of Gaza. The convoy did not stop to see it. South of the Arab city, the vehicles passed through the village of Deir el-Balach. From there, they followed what was less a road than a track in the sand.

Prof. Dothan forgot her fear. “I felt like an explorer in Egypt”, she recalls. “Sand dunes all around, beautiful orange groves heavy with fruit, little grass huts, clusters of Sudanese lined up to watch us—it was all very romantic.”

On the edge of an orange grove, the convoy stopped in an area from which the sand dunes had been bulldozed away. The earth beneath the dunes showed clear signs of illegal excavation. Prof. Dothan and the archaeologists who had come with her carefully surveyed the area. They picked up a number of pottery sherds scattered on the ground and in the holes the illegal diggers had left. Even from the sherds, the archaeologists could identify the styles and shapes of ancient Egyptian and Mycenaean potters. There was also Cypriote and local Palestinian pottery of the 14th and 13th century B.C. Then some potsherds were found that Prof. Dothan was able to identify as pieces of ceramic anthropoid coffins. That was the clincher. “I knew I had found the place.”

Prof. Dothan is a short, unpretentious, pretty woman. She reflects confidence, and, at the same time, a modesty, charm and enthusiasm that captivates her lecture audiences, as well as her students. She is one of the most popular teachers at Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology. Married to Archaeologist Moshe Dothan, Mrs. Dothan pursues her distinct archaeological interests.

Among those interests is Mycenaean and Cypriote pottery. She is one of Israel’s leading experts on the subject. That is why several sources in 1967 brought to her the news that a large number of ancient vessels in Mycenaean and Cypriote style were appearing on the Jerusalem antiquities market. Further investigation revealed that Egyptian pottery was also included. More than this, the market was offering a large inventory of jewelry—gold, beads, and semi-precious stones—, alabaster vessels and bronze weapons, Ushabti figurines and scarabs. All this was a clear sign that a new site had been discovered by someone who was secretly digging it and selling the finds illegally through the elaborate network of middlemen which ultimately reaches the Jerusalem antiquities market and private collectors.

It was obvious to the archaeologist that all of these finds were coming from a single site, most likely an ancient cemetery. Whole pottery vessels such as those that were reaching the market are rarely found in occupation sites. Most whole vessels—especially elegant ones like these—come from tombs. The jewelry, figurines, cosmetic bowls and goblets also suggested grave goods, strongly supporting the conclusion that an ancient burial ground of the 14th and 13th century had been found. (The absence of ordinary household pottery confirmed this analysis.)

But where was it? From several antiquities dealers came word that the burial site was in the Hebron area, but all efforts to locate it there failed. Then another artifact came on the market—an anthropoid coffin lid. Anthropoid coffins were shaped roughly like the human form they contained: flat on the base, and narrow at the feet; gradually widening for the body and shoulders, and rounded at the head—all in all, like a very large storage jar. On the lid a face and sometimes hands were applied. The form originated in Egypt where anthropoid coffins of stone (usually confined to royal burials), wood, cartonnage (molded linen and plaster), and pottery have been found. The anthropoid coffin lid that was brought to Prof. Dothan was made of pottery. It could be dated approximately to the same period as the pottery vessels and other artifacts which had been coming onto the market. Any doubt that these finds were coming from a cemetery quickly dissolved.

However, a careful examination of the coffin lid produced particles of sand—not the dirt that would have clung to the lid had it been buried in the Hebron area. A good guess was that it came from around Gaza. The great English archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie had excavated several rich sites near Gaza during the latter part of the 19th century with finds similar to those which had been appearing recently from the then-unknown cemetery site.

Prof. Dothan sent word through her undiscussable contacts in the antiquities market that the cemetery was in the Gaza area, not the Hebron area. Word came back that if she would like to see it, she could do so. She immediately contacted the army which agreed to take her in a convoy. That was how she happened to be riding through the sands of Gaza to the cemetery of Deir el-Balach.

Having found the site, Prof. Dothan’s natural inclination as an archaeologist was to excavate it. But this was out of the question because of security problems. She could do nothing but wait until things calmed down. For more than three years Prof. Dothan waited, and contented herself with tracing, photographing and cataloging the illegally excavated finds. These finds were scattered in private and museum collections both in Israel and abroad. The largest group of finds from Deir el-Balach is in the collection of Israeli General Moshe Dayan, the hero of the Six Day War and owner of Israel’s most extensive private archaeological collection. But many other collectors and museums have acquired pieces. These finds have proved so rich that Prof. Dothan is preparing a book about them.

Finally, in 1972, Prof. Dothan was permitted to return to Deir el-Balach to excavate. It was not, to say the least, “your usual dig.” First, the security situation still created a problem. Although the Gaza Strip was quieter than it had been in early 1968, an army helicopter hovered above the dig just to make sure. In addition, an army patrol with walkie-talkies and rifles guarded the excavators and the excavation. The archaeologists were billeted at army headquarters and were taken to the excavation each morning in army trucks. After four in the afternoon, the diggers were confined to quarters.

Even more confining than the security arrangements was the fact, as Prof. Dothan put it, that “We were at the mercy of the people who had conducted the illegal digging”. The director of an excavation normally likes to make his or her own decisions as to where to dig and how to proceed. But here these decisions were determined by what had already been dug and what had been found where. Only the illegal diggers had this information. Prof. Dothan decided “to use the cat to find the milk”. She hired the leader of the illegal dig as her chief of staff. Hamad was his name, and she refers to him good-naturedly as “the head robber”, “the chief archaeologist” and “my good friend”, depending on the context.

The excavation process also differed from the usual dig. Major effort was devoted to removing sand dunes with a bulldozer. Indeed, this was how the Arabs had found the cemetery. From the area adjacent to the orange grove, the villagers had been removing sand dunes which for millennia had covered the earth beneath. They wanted to plant the reclaimed land with orange trees. In the process, the cemetery was discovered. Now the Israelis were doing the same thing—removing sand dunes—which pleased the Arab villagers because afterward they would have more land for their orange trees.

Removing the dunes required no little effort. The dunes were between 20 and 30 feet high, the drifts of centuries. Each morning Hamad would direct the bulldozer where to work. “He acted”, says Prof. Dothan, “like the chief surgeon, dancing around with his hocus-pocus, exercising his expert judgment as to where and how to cut.”

At first, the results were poor—a few small burials, skeletons and jars, but no coffins. At the end of the day’s dig, Hamad would promise, “Tomorrow we will find a coffin”. When tomorrow also produced nothing, Prof. Dothan would say to him, “Hamad, what happened?” Hamad would reply, “Yom assal, yom bassal—one day it’s honey, one day it’s onions.”

Finally, the day of honey arrived. As the bulldozer removed one last bit of sand, exposing the earth beneath, a dark patch of earth about 5 feet by 10 feet appeared. Hamad, who had seen such patches many times before, recognized it immediately. At that point, the archaeologists knew that the next day they would be removing a coffin. Normally, the excavation of a coffin would take more than a day—to dig, record, photograph, and remove the artifacts. However, the archaeologists knew they would not be able to leave a partially exposed coffin overnight at this site. If they did, it would probably not be there in the morning.

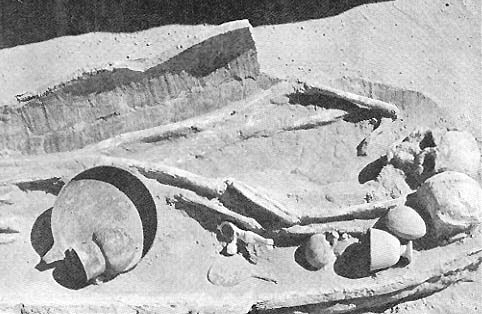

So at five the next morning the digging began. Word had spread through army ranks that a coffin had been found and half the brass in the Gaza Strip came to watch. Gradually, a beautiful example of an anthropoid sarcophagus appeared—complete. On top of it was an alabaster vase. It had not been touched since it had been laid there over 3,000 years ago. Prof. Dothan remembers it as one of the most exciting days of her life.

When the archaeologists removed the lid, they found among the rich cache of grave goods four skeletons—a man, a woman and two children. Obviously they had been placed in the coffin at the same time. This pattern was repeated in all the coffins excavated by the Israeli archaeologists, as well as those unearthed by the Arabs. None contained only a single skeleton. Were the wife and children killed when the husband died? No answer.

Anthropologists on the team determined the age of the couple by looking at the bones—they had barely reached middle age. Only when these experts announced the age of the people whose skeletons were found—by examining the condition of their bones—were the Arab diggers impressed with the ability of the Israeli archaeological team. Until then, the Israelis seemed only to be following directions.

The multiple burial in a single coffin is not the only thing that continues to puzzle the archaeologists. At the head of the coffin was a large jar, like a marker (see illustration). Why? Again no answer. On the bottom and sides of some of the coffins rows of small holes are pierced (see illustration). To allow the soul to be released? To allow moisture and body fluids to escape? Again no answer.

The first season of excavation at the cemetery of Deir el-Balach lasted only two weeks and only one anthropoid coffin was found. Prof. Dothan returned again several months later for another short season and this time she found two more anthropoid coffins. The coffin found in the first season was the key to finding the other two. From information supplied by the Arabs, who ultimately provided the Israelis with a crude map of their dig, it was clear that the anthropoid coffins were buried in groups of three or more, about 10 or 12 feet apart. All of the burials were oriented approximately to the west—to the Mediterranean Sea—a phenomenon the archaeologists have not yet been able to explain. However, with this information about the burial patterns, and with the Arabs’ assistance, the Israelis were able to locate with comparative ease two other coffins.

The last of the three coffins included the richest finds. The second of the three had been disturbed in antiquity. The third, like the first, had not been touched since it was buried there 3,200 years ago.

The day the third coffin was excavated—May 30, 1972—was a day charged with emotion. As is so often the case in Israel, neither the ancient past nor the harrowing present were far away. Here in Deir el-Balach one expected the past. But from the radio came the news that Japanese terrorists had gunned down a group of pilgrims at Lod Airport, killing 27. The archaeologists continued to dig. Quietly, peacefully, between sand dunes and orange groves, an ancient anthropoid coffin gradually appeared.

At the head of the coffin was the storage jar as marker. The coffin itself was without delineation of the head and shoulders. On the lid was a mask applied in low relief. The face was surrounded by rows of indentations meant to signify the curly hair of a wig. Below the face were stick-like arms which ended in clenched fists that almost met.

Removal of the lid revealed a dazzling sight. Inside lay two skulls almost touching one another (see illustration). Glistening through the sand that had seeped in through the cracks was golden jewelry, undimmed by the centuries. Twenty palmetto-shaped gold pendants that once graced the woman’s neck, together with gold and carnelian beads, lay beside the skulls. Five pairs of gold earrings were found in the coffin, some of solid gold crescents and others of braided gold loops with fruit-shaped elongated drops (see illustrations). On the finger bones of the female skeleton were two seal rings, one of gold and the other of dark red carnellian. Alongside the bones lay bronze and alabaster vessels. One alabaster goblet was shaped like a lotus flower, decorated with petals outlined in black paint and accentuated in red. An alabaster cosmetic spoon was shaped in the form of a nude “swimming girl”. The silvery surface of a bronze mirror was still visible where the patina had peeled off. Fourteen scarabs of faience, steatite and carnellian were found in the coffin, some with their silver and gold mountings still intact, bearing the names of such famous Pharaohs as Tuthmosis III and Ramesses II. It was a breathtaking sight.

Three coffins were all that the Israelis were able to excavate. This may seem an insignificant number compared to the 50 or more that have been traced to Hamad and his crew of diggers. But the three burials that were scientifically excavated allow the others to be placed in context as to date, provenance, and burial condition.

The coffins were made by building up coils of clay which were then shaped as desired, in the same way that large storage jars were made. When the clay was shaped and leather-hard, the lid was cut out; in that way, it fit the opening perfectly. The removable lids from Deir el-Balach extend only to the face or bust and not to the base, as do anthropoid coffin lids from some other sites. The facial features of a man, together with hair, arms and, in some cases, a beard, were applied to the lids.

After the coffin was fired, it was apparently painted. However, only a few traces of the paint have survived. On one lid, black paint was used to accentuate the hair, eyes, and nostrils; and traces of red can be seen on the cheeks and lips. Sometimes a heavy red slip covers the features; on others, a white, stucco-like slip provides a background. On one, a figure wears a lotus-petal collar which is painted yellow.

The coffins can be divided into two groups, based on their shape. In one, the head and shoulders are not delineated; the top of the coffin is simply rounded. In the other, the head and shoulders are shown, like a mummy. The first shape, with head and shoulders not delineated, is the most common shape of anthropoid coffins found in Egypt. It is the only shape that had hitherto been found in Palestine. But at Deir el-Balach, only about 10% of the coffins took this shape. The rest had head and shoulders delineated.

Anthropoid coffins developed from mummies and mummy-cases in the Egyptian Middle Kingdom. Before that, coffins were box-shaped. Burials in anthropoid coffins continued into the New Kingdom in Egypt and spread from the upper classes to other social strata, although overall the use of such coffins was not widespread.

Interestingly enough, there is no trace of mummification in the Deir el-Balach burials. Although traces of cloth from bags that held artifacts have survived, no mummification cloth has been found.

The faces on the lids are extremely varied. But they do tend to fall into groups. Some groups contain almost identical faces, indicating that they come from the same workman, or at least the same workshop, using the same pattern.

The faces can be classified according to the method by which they were applied to the coffin lid. In the first type, the faces were created as a mask complete with features indented, incised or painted. The mask was then applied to the lid. The outline of the face is thus quite distinct. Ears, wig or beard were added in applique. The result is a rather naturalistic appearance.

In the second type, the face is not separately delineated; there is no mask; and the eyes, eyebrows, nose, mouth, ears and beard were applied separately to the surface of the lid. The fact that there is no delineated facial outline gives the face a grotesque appearance, almost like a caricature of a man. One of these grotesque lids looks more like a lemur than a man (see illustration). Great saucer eyes dominate a small face which merges into a massive body. The very low-browed forehead is only faintly indicated. The head looks bald and the ears protrude from the side of the head. One might expect paws instead of the relatively naturalistic arms and hands which are placed on the chest of the coffin.

What can be said about the people buried in these strange coffins?

We know that they were Late Bronze Age people. The coffins date from the 14th to the end of the 13th century B.C. (The Exodus from Egypt was about 1250 B.C.) They are dated not only by typical pottery of the period, but also by other datable artifacts as well.

The grave goods indicate that these people were by no means poor peasants. At one time, it was thought that only the poorer classes used pottery anthropoid coffins because they could not afford mummification. According to this theory, the wealthier classes were not only mummified, but used coffins of stone, wood or cartonnage. The cemetery of Deir el-Balach destroys this theory. The poor were buried without a coffin, as the many skeletons at Deir el-Balach demonstrated. And the grave gifts such as those associated with these anthropoid pottery coffins with unmummified bodies could not have belonged to the poor.

The Deir el-Balach people were also very cosmopolitan (typical of the Late Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean), as evidenced by the Mycenaean and Cypriote pottery.

And if they were not actually Egyptian, they were surely under very heavy Egyptian influence. The anthropoid coffins themselves; the facial decorations with Egyptian wigs and Osiris beards; the scarabs with hieroglyphic writing mentioning a number of Pharaohs; Egyptian pottery and pottery forms (that is, local imitations); Ushabti figurines; lotus-flower shaped alabaster cups and jewelry; lotus-seed vessel pendants; Horus eyes; an embossed head of Hathor on a gold necklace; even Egyptian burial stelae—all reflect heavy Egyptian influence.

But who were these people?

Two theories have been proposed. One is that they were Egyptians, or more probably mercenaries, employed to administer the surrounding area which was then under Egyptian control, as was most of Canaan. That they were mercenaries employed by the Egyptians, rather than Egyptians themselves, is suggested by the fact that the artifacts differ in subtle ways from similar artifacts found in Egypt. Egyptologists who have looked at the Deir el-Balach materials say it looks Egyptian and yet is clearly not Egyptian. For example, in many cases the artist misunderstood Egyptian symbols. This has led Prof. Dothan to conclude that the people buried at Deir el-Balach were probably non-Egyptians employed as mercenaries, and under heavy Egyptian cultural influence.

This theory is consistent with the increasingly well-supported view that the Philistines originally came to Palestine as Egyptian mercenaries. According to this view, when Egyptian power waned, other Philistines joined the mercenaries to occupy the five coastal cities comprising the Philistine pentapolis.

According to wall-reliefs of Rameses III at Medinet Habu in Egypt, the Sea Peoples, including the Philistines, were defeated in 1190 B.C. by Rameses III in a great land and sea battle. Egyptians often impressed their defeated enemies into service as mercenaries to administer their far-flung territories. And, not long after their Egyptian defeat, the Philistines appear in Palestine using anthropoid pottery coffins and showing other Egyptian influence. At Beth Shean, on whose walls the Philistines hung the heads of King Saul and his three sons after their late 11th century defeat at Mount Gilboa (see 1 Samuel 31:8–13; 1 Chronicles 10:8–12), an anthropoid coffin was found in which the headdress on the face of the coffin is the same as the headdress on the defeated Philistines in the Egyptian wall-reliefs at Medinet Habu (see illustrations). The headdress consists of a strap around the forehead and a diadem of what appears to be feathers. Its appearance both at Medinet Habu and on the anthropoid coffin from Beth Shean is conclusive evidence of Philistine occupation of Beth Shean.

The anthropoid coffins from Deir el-Balach are the earliest anthropoid coffins which have yet been found in Canaan. If they belonged to Egyptian mercenaries, they represent the beginning of a tradition that was adopted by later Egyptian mercenaries, including the Philistines who arrived on the scene in the early 12th century.

The other theory as to who these people were focuses on the suggestion that Deir el-Balach may have served as a central burial ground for Canaanite dignitaries and wealthy caravaneers. The Bible seems to refer to the use of such central burial grounds when Jacob was returned to Canaan after being mummified (Genesis 50).

That is about as far as the archaeologists can go at this time. They could learn more about the people who were buried at Deir el-Balach if they could find and excavate their settlement. Dr. Dothan believes it is near the cemetery. If the settlement is not a city or a village, then at least there must be an installation for manufacturing the coffins. (Tests show that the coffins were locally manufactured. See “Using Neutron Activation Analysis to Determine the Provenance of Pottery,” elsewhere in this issue of the BAR.) Last summer, Prof. Dothan returned to the area to search for the occupation site associated with the cemetery. She thinks she has found it. Behind some sand dunes, she saw traces of mud brick, together with pottery sherds of the Late Bronze Age. Prof. Dothan hopes to go back next year for a full scale excavation.

“Perhaps then”, I suggested, “you will be able to find out who the people were who were buried at Deir el-Balach”.

“Inshallah”, she replied. “Do you know what that means? It’s Arabic—‘In the name of Allah’”.

We may close on a Biblical note. “Aron”, or coffin, is used only once in the Bible (Genesis 50:26)—in connection with Joseph’s burial. Joseph, a high-ranking minister in the Egyptian government was naturally buried in accordance with Egyptian rites, including mummification and a coffin. It is likely that his coffin resembled the anthropoid coffins unearthed at Deir el-Balach.

(For further details, see Trude Dothan, “Anthropoid Clay Coffins from a Late Bronze Age Cemetery near Deir el-Balah”, Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 22, p. 65 (1972) and Vol. 23, p. 129 (1973), Trude Dothan and Y. Bet-Arieh, “Rescue Excavations at Deir el-Balah”, Qadmoniot, Vol. 5, p. 26 (1972). Financial aid for the excavation and publication of the Deir el-Balach finds has been provided by Lionel and Sylvia Bauman and by the Samuel Ungerleider Fund.)