Excavating in Samson Country—Philistines and Israelites at Tel Batash

036

The period from the time of the Judges to the end of the Israelite monarchy is known in archaeological terms as the Iron Age. It is subdivided into Iron I, the time of the Judges from about 1200 to 1000 B.C., and Iron II, the United and Divided Monarchy, from about 1000 to 586 B.C., when the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem.

Throughout the Iron Age, Palestine was inhabited by several different ethnic groups who controlled shifting areas of the country. Although the Israelites inhabited most of the country, other peoples dominated certain regions and enclaves. These other peoples included the Canaanites (later known as the Phoenicians), the Philistines, the peoples of Transjordan and desert nomads.

One of the most challenging tasks of modern archaeological research in the Holy Land is to identify and clarify the various regional cultures of the country, to study their interrelationships and their mutual influence on one another. This is especially true when excavating in a buffer zone of one of these geopolitical regions; there the archaeologist has a special opportunity to study the interaction of various regional cultures.

The site we have been excavating for 11 years—Tel Batash is its modern name; Tella el-Batashi in Arabic (nobody knows what it means)—lies in just such a 037border zone. At various times, it was controlled by Canaanites, Philistines and Israelites, sometimes shifting back and forth among these different ethnic groups.

Our archaeological project was designed to explore the regional culture and the shifting ethnic influences that can be expected in such a buffer zone. Some of our most spectacular results and conclusions are presented here for the first time.1

We now identify Tel Batash with Biblical Timnah, 038which is a story in itself. We are in Samson country, as we shall see.

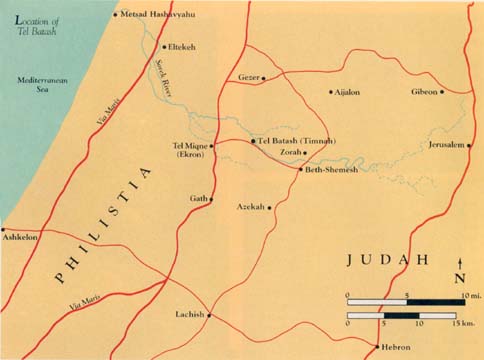

Tel Batash is located in the area known as the Shephelah,b the low hill country between the Mediterranean coastal plain and the higher, more rugged hills (the so-called hill country) of Judah. A number of broad fertile valleys traverse the Shephelah from east to west. One of these is the Sorek valley, which is drained by a small, perennial, spring-fed stream. Tel Batash stands in the Sorek valley beside this brook. It was discovered in 1871 by the eminent French scholar and Biblical archaeology pioneer, Charles Clermont-Ganneau, during a survey intended to locate the site of Biblical Gezer. Ultimately, Clermont-Ganneau was able to locate Gezer at Tell Jezer, near the village of Abu Susheh. Before doing so, however, while passing along the Sorek valley, he discovered a square mound called “Tell el-Batasheh.” Clermont-Ganneau thought it was a Roman or Byzantine military camp. After all, at this time, pottery was not yet used as a dating tool, so Clermont-Ganneau can be excused for failing to recognize the importance of the mound in Biblical times.

Tel Batash is, however, located near a number of important Biblical sites: six miles south of Gezer, five miles east of Tel Miqne (which we now know is Philistine Ekron) and five miles west of Beth Shemesh. Tel Batash is also only twenty miles west of Jerusalem. It is therefore somewhat astonishing that Tel Batash was neglected in the flurry of historical-geographical research of the country before World War II, despite its proximity to these Biblical sites. Only in 1942 did the Israeli scholar Yaakov Kaplan, followed by Benjamin Mazar, now the dean of Israeli Biblical archaeologists, recognize the importance of the mound. At first, however, Mazar suggested its identification with the Philistine city of Ekron. In the late 1950s the mound of Tel Miqne (Khirbet Muqanna) was identified as the largest Iron Age site in the entire region. Joseph Naveh first suggested that Miqne should be identified with Ekron. This identification has now been confirmed by excavations at Miqne under the direction of Trude Dothan of Hebrew University and Seymour Gitin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. If Tel Batash is not Ekron, the most logical conclusion is that it is Biblical Timnah.

The most important support for this identification is the Biblical description of the border between the tribes of Judah and Benjamin. In the Biblical description of Judah’s northern border, Timnah is mentioned as being between “Beth-Shemesh” and “north of Ekron” (Joshua 15:10–11); that is, along the brook of Sorek. Tel Batash is the only important mound along this line. So we can be reasonably confident that Tel Batash is indeed Biblical Timnah, especially because the results of our excavations are consistent with the Biblical references to Timnah.

Timnahc is frequently mentioned in the Bible. It was in Timnah that Samson’s unnamed first wife lived. Samson was born in the Israelite town of Zorah, identified with the ruined Arab village Sar’ah, on a ridge about five miles east of Tel Batash. Samson went down from Zorah to Timnah, where he met and fell in love with a Philistine woman:

“Once Samson went down to Timnah; and while in Timnah, he noticed a girl among the Philistine women. On his return, he told his father and mother, “I noticed one of the Philistine women in Timnah; please get her for me as a wife.” His father and mother said to him, “Is there no one among the daughters of your own kinsmen and among all our people, that you must go and take a wife from the uncircumcised Philistines?” But Samson answered his father, “Get me that one, for she is the one that pleases me.” His father and mother did not realize that this was the Lord’s doing: He was seeking a pretext against the Philistines, for the Philistines were ruling over Israel at that time. So Samson and his father and mother went down to Timnah” (Judges 14:1–5).

Samson’s exploits at Timnah are some of the most action-packed stories in the Bible. It was there, in the fields of Timnah, that Samson, the Danite, encountered a full-grown lion that came roaring at him (Judges 14:5). When the spirit of the Lord gripped him, he tore the 039lion “asunder with his bare hands” (Judges 14:6). Later, Samson came back to Timnah and found a swarm of bees and honey in the lion’s carcass. He scooped up the honey and ate it (Judges 14:8–9).

Samson, now married, made a feast in Timnah at which he propounded a riddle:

“Out of the eater came something to eat,

Out of the strong came something sweet.”Judges 14:14

When the people of Timnah could not guess the answer to the riddle, they prevailed on Samson’s wife to coax the answer out of him. “Then Samson’s wife harassed him with tears, and she said, “You really hate me, you don’t love me. You asked my countrymen a riddle, and you didn’t tell me the answer’” (Judges 14:16). She is ultimately successful and reveals the secret to her countrymen. Thus began a life of trouble for our Danite hero, growing out of his unsuccessful marriage to a Philistine bride. The townsmen of Timnah thus were able to solve the riddle with what may seem like another riddle:

“What is sweeter than honey,

And what is stronger than a lion?”Judges 14:18

The first part of this answer is a kind of rhetorical question implying that nothing is sweeter than honey and in effect saying that “honey” is the answer to the first part of Samson’s riddle; that is, honey came out of the lion’s head, “the eater.” The second part of the answer to Samson’s riddle is more complicated. If we ignore the fact that Samson had torn the lion limb from limb, the answer to the second part of Samson’s riddle would be the lion, the strong one out of whose head came something to eat (i.e., the honey). But Samson was stronger than the lion, and in a sense it was Samson’s killing of the lion out of which came the sweet honey. The second line of the answer to Samson’s riddle beautifully preserves this ambiguity. “What is stronger than a lion?” can imply, in a way parallel to the rhetorical question in the first line of the answer, that nothing is stronger than a lion and that therefore the answer to the second part of Samson’s riddle is a lion: Out of the strong (lion) came something to eat. Or “what is stronger than a lion?” can be understood to imply that the answer is Samson; indeed, Samson is stronger than a lion, having torn one limb from limb. Therefore the correct answer to the second part of the riddle may be Samson. Either interpretation is supportable by the text.

Samson responded to the townsmen’s successful solution to the riddle:

“Had you not plowed with my heifer,

You would not have guessed my riddle.”Judges 14:18

He clearly implies that they got the answer from his Philistine wife, perhaps even implying that they had sexual relations with her.

Samson then kills 30 Philistines at Ashkelon (one of 040the five major Philistine cities) and gives their clothing as a prize to the Timnahites who answered the riddle. Samson was in a rage, however (Judges 14:19).

Later, at the time of the wheat harvest, Samson returns to Timnah, but his father-in-law will not let him go into his wife’s chamber. “I was sure,” the father explains, “that you had taken a dislike to her, so I gave her to your wedding companion” (Judges 15:2).

Samson bursts out that the Philistines can no longer object to the harm he intends to do them. He catches 300 foxes, ties a torch between each pair of fox tails, and then lets loose in the wheat fields of Timnah the 150 pairs of foxes with burning torches. The fire consumes not only the standing grain, but also the stacked grain and the olive groves (Judges 15:3–5).

The Philistines then kill Samson’s wife and father-in-law. Samson swears revenge and gives the Philistines a thorough thrashing (Judges 15:6–8). The Philistines muster an army and confront Judah. To avoid the attack, 3,000 Judahites go to where Samson is hiding in a cave. Samson explains that “As they did to me, so I did to them.” But the Judahites bind Samson with two new ropes and deliver him to the Philistines (Judges 15:9–13).

When he is delivered to the Philistines, however Samson, gripped with the spirit of the Lord, breaks the ropes as if they had been burning flax. Then he takes the jawbone of an ass and slays a thousand Philistines (Judges 15:14–16)

Thus did Israelite tradition remember Timnah as a Philistine town during the time of the Judges, the center of tension and struggle between Israelites and Philistines.

Later, during the time of the monarchy, the Bible refers to Timnah as an Israelite town. In Joshua 19:43, it is mentioned in the list of cities allotted to the Tribe of Dan, together with other cities in this area and in the region of Jaffa.d Most scholars today believe that this list reflects conditions during the time of David and Solomon, the first time this territory was actually under Israelite control. Still later, Timnah is mentioned as having been taken by the Philistines from Judah during the time of King Ahaz (742–726 B.C.), when Judah’s military strength was diverted to its northern border by an attack of a coalition of the northern kingdom of Israel and the Arameans of Damascus (2 Chronicles 28:18).

According to this passage, the Philistines attacked and captured several cities in the Judean Shephelah at this time, including “Timnah and its villages [literally ‘daughters’e].” It appears that Timnah at this time was a prosperous urban center that even included suburbs.

Timnah is also mentioned once in an ancient source outside the Bible—on a clay prism covered with cuneiform writing, known to scholars as the Annals of Sennacherib, the Assyrian king who invaded Judah in 701 B.C. Among the cities Sennacherib boasts of having captured is Timnah.

What the town was called before the time of the Israelite judges—whether it was called Timnah or not—we have no way of knowing. But we do know there was a settlement at the site long before the Philistines settled it. Our excavations have shown that the city was founded during the Middle Bronze Age, probably in the 18th century B.C., on the level alluvial plain near the Sorek brook. From there it grew, level after occupational level. Today, Tel Batash is a superb example of an artificial mound resulting from human activity over a period of more than 1,300 years.

The original city, covering approximately six acres, was nestled within a huge artificial square crater formed by high earthen ramparts that the earliest settlers built for defensive purposes. This type of fortification is well known from other Middle Bronze Age cities in both Syria and Palestine. At Tel Batash, the plan of the Middle Bronze Age city determined the size of the city for generations to come.

We have identified 11 occupation levels in the mound, which we have numbered I to XI beginning from the top. The lowest six levels (XI–VI) represent successive occupational strata of the Canaanite city 041from the 18th century to the 13th century B.C., before the Israelites and the Philistines enter the picture.

The next four levels, reading up (strata V–II), represent cities of the Iron Age (1200–600 B.C.). These levels will be the principal focus of this article. The last level (stratum I) dates to the Persian period (sixth-fourth centuries B.C.).

We have tentatively identified the earliest Iron Age level (stratum V) as Timnah of the Philistines during the time of Samson. Until now, however, too little of this town has been uncovered to say much about its plan. Nevertheless, when the Philistines arrived, structures of the last Canaanite level were renovated and reused by the new settlers. The remains excavated thus far suggest a densely structured urban center very probably fortified by a city wall. Many of the houses are built of the typical mudbricks used in this area. We found the remains of a large building where a city gate would be built in subsequent periods. This building was probably a citadel or large fortified building of some kind.

The finds from this level V (1200–1000 B.C., the period archaeologists call Iron Age I) include painted pottery in the typical Philistine style, known from sites throughout Philistia, such as nearby Ekron.f The earliest Philistine pottery, locally made “Mycenaean III C” pottery, which is abundant at Ekron, is, however, missing at Timnah. This indicates that the Philistines occupied our site somewhat later than at Ekron. Tel Batash became Philistine only during an advanced phase of Philistine material culture, perhaps sometime between 1150–1100 B.C.

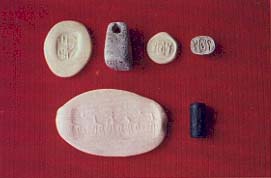

Among the special finds from this period is an interesting Philistine seal showing a schematic human figure seated and playing a lyre. Another important find was a bulla—a lump of clay bearing the stamped impression of a seal—that had been used to seal a papyrus document. Here is unquestionable evidence for writing on papyrus in Philistia during this period.g

Level V ends without a destruction. Moreover, there appears to be a gap in occupation between level V and the next level, level IV. It appears that the Philistine town at Timnah was abandoned around 1000 B.C., perhaps because of changes in the political and economic structure of the region.

As we have seen, the list of cities allotted to the 042Tribe of Dan in Joshua 19 reflects the Israelite expansion to the Mediterranean coast during the United Monarchy. Timnah obviously was taken from the Philistines and became an Israelite city. The occupational level from this period (stratum IV in our excavations) contains typical Israelite pottery of the tenth century B.C., including bowls and kraters covered with a thick red slip that was burnished by hand. This pottery resembles forms found at other Israelite sites of the same time, such as Lachish and Beth Shemesh.

The architectural remains from the tenth century indicate that the city was only partially built up. We discovered the remains of two solid towers that may have been part of the city gate. However, there was apparently no real defensive city wall. Limited security was provided by an outer belt of houses creating a defensive perimeter. Such a defensive system also has been found at other Israelite sites of this period. Inside this perimeter of houses, large open areas remained, as if the town never reached its potential development during this period. A similar situation characterizes Lachish and other sites at this time.

One of the most precious finds from this level is an incised inscription on a pottery bowl fragment. It includes the Hebrew name “[Be]n Hanan.” The letter forms closely resemble those in the famous Gezer calendar. Found at nearby Gezer, the calendar describes the agricultural year, month by month. It is generally considered the earliest Hebrew inscription of any significant length. Hebrew inscriptions from the time of David and Solomon are extremely rare, and we are pleased to add the name of “Ben Hanan” to this small corpus.

The name Hanan is especially interesting because it appears as a component of the place-name “Elon Beth Hanan” in the list of Solomonic districts relating to our region (1 Kings 4:9). Elon is mentioned before Timnah and Ekron in the list of the cities of Dan (Joshua 19:43). It thus may well be that the name Hanan in our inscription is related to the family of Hanan that dwelt in the region of Elon and Timnah during the tenth century B.C.

When Solomon died (c. 930 B.C.), the kingdom split in two—the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. Seriously weakened by this division and by the internal strife that accompanied the split, the Israelites soon became an Egyptian target. Five years after Solomon’s death, Pharaoh Shishak (Sheshonk in Egyptian records) invaded Judah. Toward the end of the tenth century B.C., Timnah was destroyed. From the description of Shishak’s campaign, written on the walls of his temple at Karnak, we know that Shishak was in this area. Yet he does not include Timnah in the list of cities he conquered, although he does list other cities in the region, such as Aijalon and Kiryath Ye’arim. It therefore seems likely that Shishak was also responsible for the destruction of Timnah at this time.

Timnah was rebuilt on a grand scale during the last two centuries of the Iron Age, the eighth-seventh centuries B.C. (levels III–II). At that time, it was a 043well-defended and superbly planned city. Our principal evidence comes from the last level (stratum II), which was heavily burnt about 600 B.C. during the Babylonian invasion under Nebuchadnezzar. Ironically, this destruction preserves and provides us with the best evidence of what the city was like at the time. Almost nothing was built after the Babylonian destruction, except a few buildings and installations of the Persian period.

In most areas of the mound, the remains of the burnt houses of the last Iron Age city appear just below surface soil. The stone and brick houses are comparatively well preserved. Under a three-foot layer of burnt debris, we found rich assemblages of pottery and other finds on the floors of the houses.

Thus, this final phase of the city was easy to uncover and clarify. It was much more difficult, however, to determine when this planned city was first built and what its history was from that time until its destruction by the Babylonians. After years of struggling with this problem, we have concluded that the basic plan of the 044city was established during the eighth century B.C. (our stratum III). At that time, the city wall and gate, the street system and many of the houses were built. We tentatively suggest that this occurred during the time of King Uzziah, who is said to have conquered parts of Philistia and built towns in it (2 Chronicles 26:6).

Earlier in this article, we referred to a passage in 2 Chronicles 28:18 that records the fact that the Philistines reconquered Timnah during the 16-year reign of King Ahaz. We found no evidence of this conquest, however.

We did find evidence of later conquest—by the Assyrian king Sennacherib in 701 B.C., thus confirming the account in the cuneiform prism we referred to earlier.

According to the Bible and the Assyrian records, Sennacherib’s invasion was a response to a revolt by Hezekiah, king of Judah, against Assyrian domination of his country. Hezekiah relied on the power of the Egyptians, with whom he allied himself. He also took precautions to secure his western frontier by forcing the Philistine city-state of Ekron to join the rebellion. Padi, the king of Ekron, opposed the rebellion, but he was soon arrested in Jerusalem and replaced by the elders of his city. Hezekiah’s policy did not pass without internal criticism, particularly from the prophet Isaiah, who warned Hezekiah that Egyptian support was a “broken reed” and that rebellion against the Assyrians was dangerous.

Hezekiah’s preparations for the Assyrian confrontation were extensive, including the fortification of the capital and the tunneling of an underground water conduit known as “Hezekiah’s Tunnel” to carry water from a spring outside Jerusalem’s city wall to a pool inside.

Other preparations included the mass production of thousands of distinctive storage jars, probably intended to transport food supplies to the Judean army during the war. Many of the handles of these jars were stamped with a royal seal including the word lamelech (belonging to the king) and thus are referred to as lamelech jars. Lamelech stamp seal impressions also contain the name of one of four cities in Judah. Seal impressions of officials related to Hezekiah’s military administration also are found on the handles of these jars.

At Timnah level III we found a storage building that was destroyed during Sennacherib’s invasion. On the floor of the building were the remains of at least 30 jars of the lamelech type. Eight had lamelech royal seal impressions of Judah. One handle was stamped with the seal of a royal official named Tsafan, son of Abimaats. Identical seal impressions have been found at Jerusalem and at Azekah, another important fortified city of Judah.

The jars at Timnah had been smashed, a human skeleton lay on the floor among the broken jars—mute but moving evidence of Timnah’s violent destruction by Sennacherib as he marched toward Jerusalem.

Similar royal jars and seal impressions (though with names of different officials) have been discovered at Lachish,2 in a context that strongly suggests that these jars were related to the Judean military organization 046preceding Sennacherib’s invasion. Both Lachish and Timnah are mentioned in the Assyrian documents as having been conquered by Sennacherib. In the Assyrian record, Timnah is mentioned after the description of a battle with Egyptian forces at Eltekeh, but before the Assyrians took the Philistine city of Ekron. Thus, Timnah appears to have been the forward line of defense of nearby Ekron. The Judean jars found in the destruction level at Timnah were probably brought there by a Judean garrison, or supplied that garrison, which arrived after Hezekiah forced Philistine Ekron to join the revolt against the Assyrians.

Our excavations suggest that after Sennacherib destroyed Timnah, it was rebuilt in the generations that followed (stratum II). Indeed, the archaeological evidence is that it flourished and enjoyed great economic prosperity until its final destruction in about 600 B.C. at the hands of the Babylonians. Excavations at nearby Ekron have revealed a contemporaneous city of similar prosperity. A comparison of the architecture, pottery and other cultural remains of the two cities demonstrates a nearly identical material culture that differs, however, from other areas of the country. The unique characteristics of the material culture of Timnah and Ekron allow us to define a distinct regional culture, quite different from nearby Judah.3

As a result of our extensive exposure of the seventh-century B.C., stratum II city (we uncovered approximately 12 percent of the entire city), Timnah is now one of the best-known cities of the Late Iron Age in the entire country. We have been especially fortunate because of the exceptionally well-preserved buildings and the large quantity of restorable pottery assemblages.

The fortification system of Timnah in the eighth-seventh centuries B.C. consisted of two defensive lines. Along the ridge of the mound, a city wall was built in the eighth century B.C. In the seventh century, this wall was reinforced to a thickness of over 12 feet. Encircling the mound one-third of the way up its steep slope, a retaining wall gave the appearance to enemies approaching the city of a second city wall. The surface of the slope between the two walls was reinforced against penetration and erosion by courses of stones, creating a glacis.

This double-walled fortification system provided an excellent defense against the battering ram, the major danger to fortified cities in the Iron Age. A similar double-wall system has been uncovered at Lachish, and this system may well have existed at other Iron Age cities in the country.

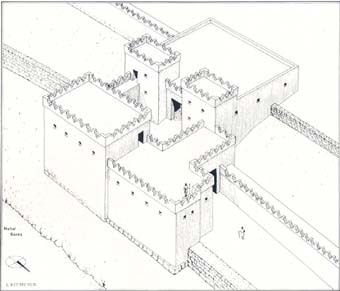

Access to the city was through a formidable gate complex, consisting of an outer and an inner gate structure. The gate complex, which faces the nearby Sorek brook, was approached by a ramp supported by retaining walls along the eastern slope of the mound. A massive tower, constructed on the alluvial plain at the foot of the mound, was an integral part of the outer gate complex. This tower’s solid stone foundation, which is all that has survived, is 75 feet long and over 25 feet wide. Its superstructure, probably built of mudbricks, could easily have reached a height of 25 feet. Passage through the outer gate led to a courtyard where a 90-degree right turn gave access to the inner gate and the town plaza beyond.

We found two building phases of this inner gate structure. In the earlier phase (the eighth century B.C., stratum III) a series of six piers and two towers flanked the central passageway, forming a gate structure with six guard chambers, three on each side. This was probably destroyed by Sennacherib. When it was replaced in the seventh century by a shorter inner gate, it was reconstructed with four guard chambers, two on each side.

The city-gate area was more than simply a fortified entrance to the city. A large square or piazza inside the city, adjacent to the gate, served as a marketplace and as a focal point of the city’s social life. We exposed part of this piazza in stratum II, the seventh-century city. It was paved with small pebbles from the riverbed at the base of the mound.

The public buildings of the eighth-century city were unfortunately not well preserved. Inside the city, near the gate, we discovered the remains of a large building, but its plan is still unclear. The fact that it contained a large rectangular hall indicates that it may have been the local governor’s palace. This is also suggested by the fact that its walls are 7 feet thick. After it was destroyed by Sennacherib in 701 B.C., it was replaced by dwellings and an industrial zone. A public building of the seventh-century city was located in the northeastern corner of the city, but it too was poorly preserved. Another building, of which only a small part was uncovered, had a row of monolithic pillars resembling Iron Age storehouses found elsewhere in the country, at such places as Beer-Sheva and Hazor.

In the northeastern part of the city, we uncovered a 10-foot-wide street that bordered the city wall. On the other side of the street was a row of houses typical of Iron Age dwellings. The wall bases are built of stone and have mudbrick superstructures. These houses contain an inner courtyard divided by a row of pillars (single, elongated, square-shaped stones). One house, to our surprise, had round pillars. This, however, is a unique feature, otherwise unknown in the many Iron Age houses that have been excavated all over the country.

The pillars supported a roof or second-story living quarters. Under this area, the courtyard was paved with cobblestones and was probably used to provide shelter for small domestic animals. On the other side of the pillars was an open courtyard paved with plaster. This area was probably used as a work and service area. Here food was prepared and cloth woven.

In one house we found three stone steps of a staircase leading to the second floor. Other houses may also have had such steps (or wooden ones), although they have not survived. Rooms adjoining the courtyard together with rooms on the upper floor provided living quarters for the family that occupied the typical house. All family dwellings appear to have served also for home 048industry. This is evident from two types of industrial installations found in the courtyards of the houses. One definitely can be identified as an oil press. The purpose of the other type has as yet to be determined.

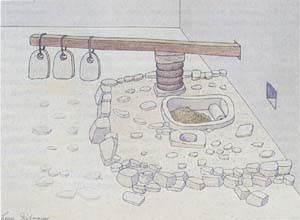

The oil presses are of the same basic design known to us from other contemporaneous Iron Age sites in the Shephelah, including Tell Beit Mirsim, Gezer, Beth Shemesh and particularly Ekron, where over 100 such oil presses have been discovered. Each olive oil installation consists of a crushing basin flanked by two pressing vats. The crushing basin was a shallow stone trough, where the olives were crushed with heavy stone rollers. The crushed olive mash was then transferred into relatively flat straw baskets that were stacked on the two pressing vats The latter were large, rounded or squared stones hollowed to form a container with a concave upper surface that directed oil oozing from the baskets toward a round central opening. These vats served as sediment containers from which the oil later was dipped for sale or for transport to storage.

Heavy stone weights suspended at the end of a long wooden beam anchored at the other end in a niche in the adjoining wall provided the pressure to squeeze the oil from the mash in the baskets. Such oil press installations are known in Hebrew as Beit Bad, “house of the beam,” an obvious reference to the large wooden beam used in the extraction process.

Although these olive oil presses are found in private homes both at Timnah and at other Iron Age sites, the prominence of oil presses here and especially at nearby Ekron indicates that oil production in the region was far greater than was needed for local consumption. 049Olive oil from this area must have been a major export product—to Egypt, Phoenicia and perhaps even to Greece (compare Ezekiel 27:17; Hosea 12:2). Oil production for export probably accounted for much of the region’s prosperity.

Another kind of home industry employed a deep stone vat and a shallow stone trough set into an exterior wall of the house near the entrance, possibly to facilitate drainage into the street. Unfortunately, we still don’t know what these installations were used for. They may have been part of a textile industry, where the flax or wool was dyed. Some process requiring disposal of liquid waste seems indicated. We do know that weaving was a common home craft at Timnah (as well as in other Iron Age sites), because we found several collections of clay loom weights in the houses we excavated.

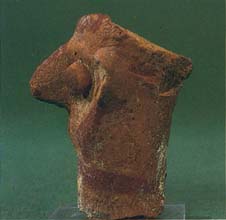

At the edge of a small piazza adjoining a residential area, we found what appears to be a local cult place. On a raised plastered platform built of mudbricks, we discovered two painted pottery chalices and, nearby, fragments of other cult objects (possibly standing stones). This cult place was founded in stratum II and therefore dates to the seventh century B.C. A cult place may well have existed here earlier, however, because nearby, in stratum III, we found three pottery molds for casting female figurines.

The city’s prosperity and thriving economy is reflected also in the large number of pottery vessels found on the floors of the houses, beneath debris from the destruction that befell the city in about 600 B.C. when Nebuchadnezzar marched through the land. We have completed a pottery restoration process that provides us with an excellent picture of the nature of the household wares in several individual houses. The number of pottery vessels in each house is quite astonishing. Over 100 vessels were found in each of two houses in the northern sector. The pottery assemblage includes bowls, kraters, storage jars, jugs, dipper juglets, bottles, lamps and drinking chalices. Most of the vessels are typical of this part of the Shephelah, known primarily from our excavation and from Ekron. Other vessels are typical of Judean ware, known from late Iron Age contexts at such sites as Jerusalem and Lachish. A few vessels reflect distant origins; among these vessels are several from Transjordan, some Phoenician imports and a few fragments of Greek pottery. The Greek pottery implies relations with Greece in the late seventh century B.C., a fact previously reflected only at a few sites along the eastern Mediterranean coast. One of these coastal sites, Metsad Hashavyahu, located near the mouth of the Sorek, is the terminal of the road passing through Timnah along the Sorek valley. The Greek wares were probably unloaded at a coastal site like Metsad Hashavyahu and then traded inland.

During most of the seventh century B.C., Assyrians ruled the entire Land of Israel, except for Judah. An Assyrian administrative center was located at Gezer, just six miles north of Timnah. The Assyrian influence is reflected at Timnah in local bowls and bottles that imitate Assyrian forms. One of these had been inscribed with the name of its owner. Unfortunately, only the first part of the name, “belonging to Maa,” was preserved.

Commercial relations in the seventh century B.C. were carried out by means of barter, or equivalent value in the form of precious metals, especially silver. Minted coins were introduced in this area only much later. The use of raw metal valued by weight required marked stone weights. A large assortment of such stone weights of well-known Judean types have been recovered at Timnah. They consist primarily of a shekel series. A special mark ( ) identifies the shekel, which had an average weight of 11.4 grams. Other marks identify the number of shekels of the particular weight (1, 2, 4 or 8). PYM was another weight unit used at the time and found at Timnah.

) identifies the shekel, which had an average weight of 11.4 grams. Other marks identify the number of shekels of the particular weight (1, 2, 4 or 8). PYM was another weight unit used at the time and found at Timnah.

It is not clear whether Timnah was part of the kingdom of Judah in the seventh century B.C. or was part of the independent city-state of Ekron. The latter situation is probably the correct one, though the Judean system of weights was used here.

The excavations of the seventh-century level at Timnah have revealed a new, previously unknown regional culture of the Iron Age. The recent excavations at Ekron complete the picture; together the two excavations provide a composite portrait of great economic prosperity in the seventh century B.C. in this region on the border of Judah. The production of olive oil and perhaps of flax or other textiles brought significant economic wealth to the cities of this region. The period of prosperity came to an abrupt and tragic end when the two main cities of the region—Ekron and Timnah—again suffered extensive damage in about 600 B.C. under circumstances that must be related to the Babylonian invasion of the region, which ultimately culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem a few years later, in 586 B.C.

The period from the time of the Judges to the end of the Israelite monarchy is known in archaeological terms as the Iron Age. It is subdivided into Iron I, the time of the Judges from about 1200 to 1000 B.C., and Iron II, the United and Divided Monarchy, from about 1000 to 586 B.C., when the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem. Throughout the Iron Age, Palestine was inhabited by several different ethnic groups who controlled shifting areas of the country. Although the Israelites inhabited most of the country, other peoples dominated certain regions and enclaves. These other peoples included the […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

By commonly accepted convention, “tell” is the spelling of the Arabic word, and “tel” (as in Tel Aviv) is the spelling of the same Hebrew word, meaning mound, an artificial hill formed by successive occupation levels of an ancient settlement.

Harold Brodsky, “Bible Lands: The Shephelah—Guardian of Judea,” Bible Review, Winter 1987.

Timnah in the Shephelah should not be confused with the copper mines of Timna, north of Eilat. The former has an h at the end, the latter an ayin. The name Timna appears as a place name in Edom (Genesis 36:40) and in modern times was tentatively given to the valley north of Eilat on the basis of phonetic resemblance to the Arabic name of the valley (Meneieh).

This same Biblical passage notes that “the territory of the Danites slipped from their grasp.” So the Danites migrated to the north, captured Leshem (called Laish in Judges 18:7ff), and renamed it Dan (Joshua 19:47).

Ian W. J. Hopkins; “The “Daughters of Judah” Are Really Rural Satellites of an Urban Center,” BAR 06:05.

Trude Dothan, “What We Know About the Philistines,” BAR 08:04.

This of course is a subject for an article in itself. Regrettably scholars have still not found any clear evidence of the language the Philistines used, nor have they succeeded in deciphering the two or three extremely short inscriptions that have been tentatively identified as Philistine. See Robert R. Stieglitz, “Did the Philistines Write?” BAR 08:04.

Endnotes

The archaeological project at Tel Batash (Timnah) was sponsored from 1977 to 1979 by the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary (with additional funding from Mississippi College and Louisiana College) and since 1981 by the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary at Fort Worth, Texas, both in collaboration with the Institute of Archaeology of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. George L. Kelm is expedition director and Amihai Mazar is archaeological field director. The permanent core staff included Osnat Misch-Brandl (1977–1979); Baruch Brandl (1982–1987), Thomas V. Brisco (1982–1984), Daniel Browning (1984–1986); Merilyn Copland (1983–1987), Moises Fleitman (1982–1987), Linda L. Kelm (recruitment and restoration) and Leen Ritmeyer (architect).

A permanent exhibit on the history and material culture of Timnah is housed in the Charles D. Tandy Archaeological Museum on the campus of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, Fort Worth, Texas.

For further reading, see: George L. Kelm and Amihai Mazar, “Three Seasons of Excavations at Tel Batash-Biblical Timnah,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (BASOR) 237 (1982), pp. 1–36; Kelm and Mazar, “Tel Batash (Timnah) Excavations, Second Preliminary Report (1981–1983),” in BASOR Supplement 23 (1985), ed. Walter E. Rast, pp. 93–120.

David Ussishkin, “Answers at Lachish,” BAR 05:06.