027

Minoans

J. Lesley Fitton

(London: British Museum, 2002) 224 PP., $45

Around the turn of the last century, a young Bostonian named Harriet Boyd wanted very much to dig at Corinth. She was a student at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, which in 1896 had begun important excavations in the ancient city. However, the school’s director, Rufus Richardson, would have none of it: Field archaeology, he believed, was not a suitable activity for a proper young woman. So Harriet Boyd ventured on to Crete, which then, as now, was a place beyond the realm of normal social convention. Between 1901 and 1904 she excavated at the coastal site of Gournia, uncovering what is still the only known town on Crete dating to the Late Minoan period (1600–1100 B.C.).

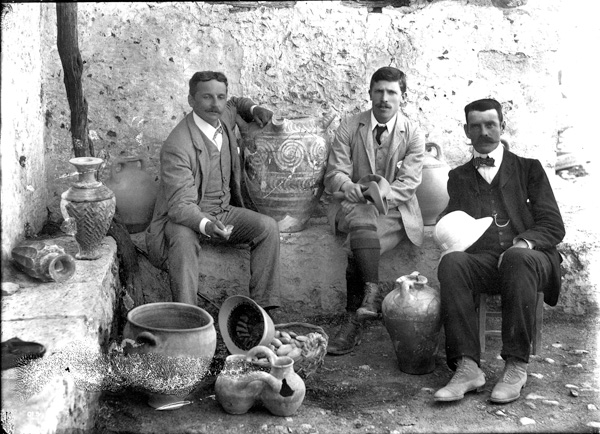

Boyd’s timing happened to be perfect. Minoan archaeology had begun in earnest just a year before she began work in Gournia—in 1900, when Sir Arthur Evans started excavating at Knossos. At this point, very little was known about the Minoans, who hadn’t even been named yet. When Boyd reached Crete, an entire ancient civilization was waiting to be discovered.

As it turned out, the field would be dominated by larger-than-life figures who imposed their ideas (and fantasies) upon generations of successors. The questions they tried to answer were tantalizing and elusive. Who were the Minoans? Where did they come from? How did they build such monumental palaces whose walls were decorated with vibrant, colorful frescoes? Was there really a King Minos, and was there any historical truth to the lurid stories of the labyrinth and the Minotaur, Theseus and Ariadne, and Daedalus and Icarus? How could such a brilliant civilization suddenly disappear?

In the archaeology of Crete, myth is almost inextricably entwined with fact—and that, in itself, is good reason to welcome an exciting yet sober new book by J. Lesley Fitton, assistant keeper of Greek and Roman antiquities at the British Museum. Her Minoans is the best general work on Minoan civilization ever published. It is concise, balanced, up to date and very well written. Anyone who reads Minoans will want to book the next flight to the Cretan capital of Heraklion.

A basic problem faces anyone who attempts to write about Minoan archaeology: the lack 028of archaeological publication. Very few excavated Minoan sites have received anything resembling a final excavation report. (Harriet Boyd was a rarity; she published her final report on Gournia in 1908, the first final report in the field of Aegean archaeology.) What has been published is often idiosyncratic. The Palace of Minos, for example, which Evans published in five volumes between 1921 and 1936, isn’t so much an excavation report as a series of impressionistic, interpretive essays. Evans’s views on Knossos and Minoan civilization are impressive in their sweep and verve, but little substance exists beneath the surface of his prose. That is why, in recent debates on subjects such as the date of Knossos’s Linear B tablets (Linear B is one of three scripts found on Crete; see the following article by Barry Powell), scholars have been forced to go back to the excavation day books and the notes taken by Evans’s assistant, Duncan Mackenzie, who, unlike Evans, was a trained excavator.a

029

Minoan archaeology has been dominated by three national archaeological schools. The British have excavated at Knossos, the French at Mallia, and the Italians at Phaistos.b Knossos has been excavated continually since the Second World War, but most of this work remains unpublished. The odd exception, paradoxically, is a structure called the Unexplored Mansion. This building, with its large pillared central hall and frescoes, was destroyed (no one quite knows how) before it was even finished in the 14th century B.C.

The second most important Minoan site on Crete is Phaistos, located in the island’s richest agricultural region. As Knossos is indelibly associated with Sir Arthur Evans, Phaistos is associated with Doro Levi (1898–1991), the director of the Italian School of Archaeology in Athens from 1947 until 1977. Of diminutive stature, and known for excavating in a white linen suit and a Panama hat, Levi produced a series of dazzling final reports on his excavations at Phaistos (1976–1988). But to plunge beneath the surface of these volumes is to enter into darkest night. Take any object from the site and try to put it back into its original context. It usually cannot be done. The details of a careful, stratigraphic excavation are simply lacking. They were never recorded. Levi knew how to run an excavation; he did not know how to excavate.

Sitting on the tip of a ridge, Phaistos is a picturesque but geologically unstable site. The initial palace at Phaistos collapsed due to this instability, and a second one was built after 1700 B.C. Very likely, the collapse of the Phaistos palaces, and the subsequent decline of Phaistos as a center of power, allowed for the rise to prominence of nearby Ayia Triadha in the 14th and 13th centuries B.C. (Although Ayia Triadha was not a palace site, some of our finest examples of Minoan art have come from there, including a painted limestone sarcophagus, the Chieftain’s Vase, the Boxers’ Vase and the Harvesters’ Vase. Ayia Triadha also has fine examples of Minoan wall painting, a form of decoration almost completely lacking in the palace at Phaistos.)

The last of Crete’s triumvirate of Minoan palace sites, Mallia, located on a coastal plain in southern Crete, flourished from about 2000 to 1700 B.C. Although Mallia was discovered and excavated by the Greek archaeologist Joseph Hazzidakis in 1915, excavation rights were turned over to the French School of Archaeology in Athens in 1922. Since then all work at the site has been carried out by French and Belgian archaeologists.c

But where, one might ask, were the Greeks? The Greek Archaeological Service in fact carried out many excavations on Crete, especially in the 1920s and 1930s, but it did not work on a palace site until 0301961, when Nicholas Platon, then Crete’s ephor (director) of antiquities, began digging at Zakros, on the far eastern coast of the island. Platon uncovered a new palace site with spectacular finds, including Linear A tablets, a rock-crystal rhyton (drinking horn) and a stone rhyton depicting a sanctuary in a rocky landscape. Platon described all these finds in a popular 1971 book, Zakros: The Discovery of a Lost Palace of Ancient Crete.

Unfortunately that is just about all that Platon ever published on Zakros. The site has become something of an object lesson on how not to conduct a major excavation. Platon went on digging year after year, taking all his finds to the museum in Heraklion at the end of each season. And there they sat. There was no preliminary study of the pottery from the site; indeed, the pottery was not even washed and restored. Following Platon’s death in 1992, his son Eleutherios inherited the excavation. He is now faced with the awesome task of working through all of this material to publish a series of final reports on the Zakros palace.

Here we come back to the problem of archaeological publication—or rather, the lack of it. Some of the most important excavations carried out by Greek archaeologists on Crete since the 1970s remain largely unpublished, with vast quantities of excavated material languishing in museum storerooms. This program of all excavation and no study has characterized Minoan digs at the sanctuary atop Mount Juktas, the administrative site of Monastiraki and the quasi-palatial site of Petras. The problem doesn’t just lie with the Greeks; many British and American archaeologists may also in the end fail to publish their research.

Things were not always this way. Joseph Hazzidakis, the discoverer of Mallia and the founder of the Heraklion Museum, excavated a major Late Minoan villa at Tylissos between 1909 and 1913, and published the results of his excavations in 1921. Stephanos Xanthoudides, a towering figure in the early days of Minoan archaeology, whose statue is right across the street from the Heraklion Museum, excavated a series of Early and Middle Minoan tholos tombs in the Mesara valley from 1904 to 1918. His final report, The Vaulted Tombs of Mesara, was published in 1924. It remains one of the most important books in the entire literature on Minoan archaeology.

The great Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos—perhaps best known for his excavations at Akrotiri, on the island of Thera (modern Santorini), in the late 1960s—published a series of detailed reports on all of his excavations on Crete in major Greek periodicals. Somehow, after Marinatos, things fell apart. In the island’s new museums at such places as Chania, Rethymnon, Ayios Nicholaos and Siteia, almost everything on display is unpublished. The situation is unacceptable, but no one seems to want to do anything about it. The longer things continue like this, of course, the more hopeless the situation becomes.

Fitton provides an excellent introduction to several complex issues that are, at present, at the very heart of Minoan scholarship. There is, to name one such issue, the controversy over the Late Bronze Age eruption of the volcano on the island of Thera/Santorini (about 80 miles northeast of Crete), an eruption many times more powerful than the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, which killed more than 36,000 people. The Thera eruption is now said to have been equal in magnitude to the 1816 eruption of Tambora (in Indonesia), the greatest volcanic eruption in the past 10,000 years.

Going back to his classic 1939 article in Antiquity, Spyridon Marinatos was always convinced that Thera held the key to understanding the collapse of Minoan 031civilization. He was sure that the volcanic eruption of Thera brought it all to a violent end, specifically that the physical events caused by the eruption (tidal wave, ejection of huge boulder-sized rocks, fallout of pumice and ash) resulted in the destruction of Crete’s splendid palaces. But Marinatos’s intriguing hypothesis needed to be tested in the field.

When the military junta took control of Greece in April 1967, Marinatos knew that his time had come. His politics matched those of the colonels now running the country, and Marinatos was appointed inspector general of antiquities. He promptly marshalled all the forces of the Greek Archaeological Service and began excavating at Akrotiri, on the southern coast of what was left of Thera. But as he and other scholars worked through the pottery from Akrotiri, it soon became clear that the correlation between the eruption and the end of Minoan civilization could not be sustained.

The palaces of Crete came to an end in a series of destructions associated with the end of a phase of Minoan pottery known as the Marine Style and equated with the chronological period known as Late Minoan IB (see chart). But the Theran volcano erupted toward the end of the Floral Style of Minoan pottery, associated with the chronological period known as Late Minoan IA. The end of Late Minoan IA is usually placed around 1500 B.C., and the end of Late Minoan IB is usually placed around 1450 B.C. The evidence of the pottery, then, puts the volcanic eruption on Thera at around 1520 B.C. But the Minoan New Palace period did not come to an end until 70 years later. According to Marinatos’s reasoning, the Theran eruption could not have destroyed the Minoan palaces of Crete.

The debate, however, was far from over. In the 1970s an argument was put forth (its leading proponent being Temple University archaeologist Philip Betancourt) that a sufficient number of radiocarbon dates from eruption contexts at Akrotiri seemed to cluster together, suggesting a date for the eruption of around 1620 B.C., one hundred years earlier than the traditional date. Climatic data from ice cores in Greenland and the tree rings being studied by archaeologist Peter Kuniholm in his dendrochronology lab at Cornell University appeared to support the earlier dating, indicating a serious deterioration of the climate in the 1620s that could only be explained by the Theran eruption.d

This has posed a difficult problem. If the Minoan chronology has to be refigured, with Late Minoan IA actually coming to an end around 1600 B.C., this would affect the entire chronology of the Late Bronze Age and thus our understanding of the archaeology of the eastern Mediterranean. As Fitton indicates, the problem seems unresolvable on the basis of the present evidence.e Until we learn more, we will simply have to live without knowing for certain whether the 034Theran eruption caused the destruction of the Minoan palaces on Crete.

Fitton largely ignores two very important Minoan sites: Kommos and Syme. Kommos is not a palace or a palatial site, not a villa or a town or a peak sanctuary or a shrine. Rather, Kommos was a seaside mercantile emporium, with massive, monumental stone architecture, elaborate harbor installations (including ship sheds) and a very impressive array of finds. Kommos has more Canaanite jars than any other site in the Aegean. It has Egyptian pottery, Italic pottery, Cypriot pottery and even Nuragic pottery from Sardinia. It has fragments of copper oxhide ingots, an exceptionally well-preserved Minoan pottery kiln and, from the post-Minoan period, an early Greek sanctuary with its own Phoenician temple. The temple contained Phoenician pottery going back to the tenth century B.C., as well as a Phoenician tri-pillared shrine.

Joseph and Maria Shaw have been excavating at Kommos since 1976, on behalf of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, and have managed to publish four massive final volumes (with more to come). Meanwhile, Angeliki Lebessi has been excavating at Syme, on behalf of the Greek Archaeological Society, since 1972. The Heraklion Museum has a very impressive display of finds from Syme, with magnificent bronze cut-out plaques with engraved decoration, bronze figurines of both humans and animals, bronze tripods and stands, and two extraordinary long bronze swords with delicately engraved decoration dating to the Late Minoan I period (1600–1450 B.C.). Despite these finds and several reports and articles documenting the site, few archaeologists know much about Syme.

One probable reason for this relative obscurity is the fact that no tourist ever makes it to the site. Syme is located some 3,700 feet up Mount Dikte, which lies to the southeast of Heraklion; no real road leads to the site, and no signs tell you where to go. Those who persevere are rewarded with one of the most spectacular sites in the Mediterranean world. No wonder that pilgrims from all over Crete made their way to Syme in antiquity to dedicate bronze votive offerings and make animal sacrifices.

Sites such as Kommos and Syme show that Minoan archaeology has more to offer than just palaces, wall paintings and reconstructed scenes of bull-leaping ceremonies. Some of the most exciting (and controversial) discoveries in Minoan archaeology during the past 30 years have taken place in non-palatial contexts.

Since 1964 Yannis Sakellarakis and his wife, Efi Sapouna-Sakellaraki, have been excavating in the general area of the village of Archanes, south of Heraklion. What they have uncovered is a complex of sites with spectacular finds that go back into the Early Minoan period (3200–2100 B.C.).

Fitton gives an excellent account of Early 036Minoan burials at the Phourni cemetery, on a hilltop near Archanes, but her main interest centers on the remarkable discoveries made in 1979 at the site of Anemospilia (Caves of the Wind, in Greek), at the northern end of Mount Juktas. At a freestanding tripartite shrine, unlike any other building in Minoan archaeology, evidence was found for the human sacrifice of an adult male, who had been bound and placed upon the shrine’s altar. Against the belly of the victim was found a massive spearhead of a type that must have been used in boar hunting. On one of the fingers of his left hand was a silver ring plated with iron.

The archaeologists explained this evidence in the following way: A man was about to be sacrificed to avert some imminent disaster. But a massive earthquake—the very one that put an end to the Old Palace period around 1700 B.C.—interrupted the ceremony. Another young man, who was about to leave the sacrificial chamber carrying a remarkable vase decorated with bulls (the vase was meant to hold the blood of the sacrificial victim), was crushed by tumbling blocks of stone.

This interpretation of the archaeological 037evidence captured worldwide attention, especially after the publication of a spectacular article in the February 1981 issue of National Geographic.

Such finds were totally without precedent in Minoan archaeology. Of course, human sacrifice is a common theme in later Greek mythology and in the literature based upon that mythology. Agamemnon, for example, sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia to bring about the favorable winds necessary for the Greek fleet to sail from Aulis to Troy.f But this was the stuff of myth—and weren’t the Minoans a peace-loving people, a community of sailors and artists?

Interestingly, the man about to be sacrificed at Anemospilia was trussed up just like the sacrificial bull shown on a painted limestone sarcophagus from Ayia Triadha. A vessel excavated at Anemospilia, probably intended to be used to collect the victim’s blood, is very similar to a vessel shown in the sacrificial scene on that sarcophagus. The evidence suggests that human sacrifice, while not a normal part of Minoan cult practice, was at least resorted to in times of emergency.

Also in 1979, an even more shocking discovery was made at a house in Knossos by Peter Warren of Bristol University, one of the senior members of the British School at Athens and a scholar involved in the excavation of Knossos for more than 30 years. Warren excavated the bones of four or five children, between the ages of 8 and 12, who had been sacrificed. From cut marks on the skeletons, Warren concluded that the flesh had been stripped from the children’s bones. (Because Warren was fully aware of the implications of what he was proposing, these bones were subjected to what was probably the most detailed physical examination of skeletal material in the history of Aegean archaeology.) According to Warren, the evidence suggested that the flesh was cooked with snails (though some evidence suggests the snails are modern) in a cannibalistic ceremony designed to ward off forthcoming disaster. Cooking human flesh was bad enough, but cooking it with snails gave the impression of a real banquet.

Fitton’s account of the finds at Knossos in the summer of 1979 is not up to the standard of the rest of the book. She clearly does not like the idea that the Minoans could have been capable, however extreme the circumstances, of such atrocities.

Nor is it surprising to find that Minoan archaeologists generally disagree with these interpretations of the evidence from Anemospilia and Knossos. Very few have even accepted the existence of a tripartite shrine at Anemospilia. The building was only partially excavated, they argue, and what was excavated has not been fully published. The same kind of argument is made regarding Peter Warren’s discovery: Although the children’s bones have been studied in great detail, the final report on the excavation has yet to appear. Our revulsion toward cannibalism is so strong that almost any other interpretation of the evidence is going to be given preference.

All in all, however, Fitton’s Minoans takes the relatively scant available material and produces a magisterial account. She is able, moreover, to communicate a passion for the Minoans, whom she describes as “a lively-minded people, with the outward-looking adventurous spirit of an island race.” Perhaps we can forgive her for finding it hard to think ill of them.

Around the turn of the last century, a young Bostonian named Harriet Boyd wanted very much to dig at Corinth. She was a student at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, which in 1896 had begun important excavations in the ancient city. However, the school’s director, Rufus Richardson, would have none of it: Field archaeology, he believed, was not a suitable activity for a proper young woman.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Susan Heuck Allen’s review of two books—Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of Minoan Myth (Hill and Wang, 2000) and Duncan Mackenzie: A Cautious Canny Highlander & the Palace of Minos at Knossos (Univ. of London, 1999)—in Archaeology Odyssey, September/October 2003, p. 60.

Although the Germans have never played any significant role in Cretan field archaeology, they have made major contributions to the study of Minoan art and architecture. The Americans got off to a great start in the first two decades of the 20th century, with Harriet Boyd and Richard Seager, who dug at Mochols, Pseira and Vasiliki. But they lost interest in Crete after 1920 and were not to return to the island for more than 50 years.

Mallia is, in many respects, the best published of all the Minoan palace sites, with 33 volumes of preliminary and final reports.

Dendrochronology involves counting the annual growth rings of trees, enabling scholars to study not only chronology but also climate. The nature of the annual growth ring formed by a tree reflects the climate during the growth year. Warm, wet years produce thick rings; cold, dry years produce thin rings.

For more on the subject, see Sturt W. Manning, A Test of Time: The Volcano of Thera and the Chronology and History of the Aegean and East Mediterranean in the Mid Second Millennium BC (Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 1999).

See Theodore H. Feder and Hershel Shanks, “Iphigenia and Isaac: Saved at the Altar,” Archaeology Odyssey, May/June 2002.