033

Moses Wilhelm Shapira is best known for the so-called Shapira Strips, narrow fragments of supposedly ancient parchment on which were inscribed a somewhat different version of the Ten Commandments from Deuteronomy than is known from the Bible. Said to have been found in the cliffs east of the Dead Sea, they were written in the ancient Semitic script used before the Babylonian Exile. Shapira sought to sell them to the British Museum for a million pounds. When he arrived in London in 1883, he allowed two of the 15 strips to be 034exhibited to the public. The crowds went wild. Even the British prime minister, the deeply religious William Gladstone, came to view the exhibit.

The Jerusalem antiquities dealer’s celebrity was to be short-lived, however. His nemesis, the French scholar Charles Clermont-Ganneau, denied access by Shapira to the 13 undisplayed strips, joined the crowds to examine the two displayed strips, dimly lit in a glass vitrine. This was enough for him to declare the strips forgeries. Soon thereafter the eminent British Old Testament scholar Christian David Ginsburg, who had access to all the strips, reached the same conclusion: They were fakes. Thus exposed, Shapira snuck out of London, leaving the strips behind. He wandered aimlessly about Europe for six months, ending up at the Hotel Bloemendaal in Rotterdam. There, on March 9, 1884, he put a pistol to his temple and pulled the trigger.

This is not the whole story, however. Shapira was, in fact, a master forger with a long history in the craft. Not that he was so skilled, but he knew the market and managed to fool some of the greatest experts in Europe.

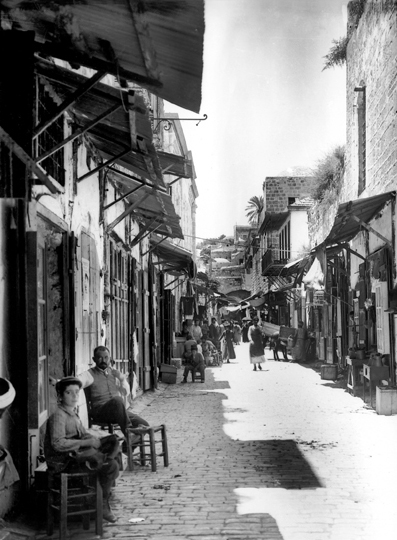

Moses Wilhelm Shapira was born in 1830 of Jewish parents in the part of Poland, Kamenets-Podolski (now in the Ukraine), that had been annexed by Russia. (Incidentally, the violinist Isaac Stern was also born there.) Shapira’s father was the first in the family to immigrate to the Holy Land. Some years later, at age 25, Shapira followed, traveling with his grandfather, who died on the trip. According to Shapira’s application for Prussian (German) citizenship, he spent five months in Bucharest on his way to Palestine. “My relationship with missionaries there convinced me of the truth of the Gospels,” he wrote, “and I was received into the Christian fold by holy baptism.” In Jerusalem, he became part of the community of Anglican converts and soon opened a small shop on Christian Quarter Road for pilgrims, where he sold dried flowers, olive-wood figurines and crosses, made-to-order olive-wood Bible covers, old books and manuscripts, as well as ancient pots and oil lamps brought to him by Arab farmers.

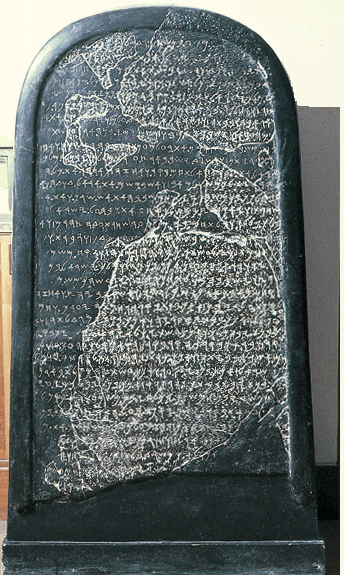

Shapira would probably have lived a quiet life as a poor antiquities dealer had it not been for a spectacular archaeological find that would change his life forever. In 1868, not long after Shapira opened his shop, some Bedouin showed a German medical missionary ministering in the land of Moab, east of the 036Jordan River, a black slab with ancient Semitic writing on it.a More than 3.5 feet tall and 2 feet wide, the stela soon became a prize for which the French, British and Germans competed. The French were represented by a young consular official and archaeological devotee named Charles Clermont-Ganneau—the same Clermont-Ganneau who would later figure in the saga of the Shapira Strips.b Since these Westerners were so interested in the stela, the Bedouin assumed that some treasure lay inside it.

At least that is one story.c What is uncontested, however, is that they broke the stela into pieces by alternately heating and cooling it. Most of the 38 pieces, including the larger fragments, were acquired by Clermont-Ganneau for the Louvre. The British graciously gave the Louvre the 18 small pieces they had acquired, as did the daughter of German scholar Konstantin Schlottmann, who owned one fragment of the stela, and who would later vouch for the authenticity of inscriptions on Shapira’s pottery collection. All in all, the Louvre has about two-thirds of the text; part of the missing third has been reconstructed from a copy of seven lines of text made before the stela was broken—interestingly, a copy made by Shapira’s assistant Salim al-Kari (or Selim el Gari), who figures importantly in our story.d

The text turned out to be the ninth-century B.C. Moabite king Mesha’s account of his revolt against the Israelites. Known as the Mesha Stela or Moabite Stone, it parallels the biblical account in 2 Kings 3, though it gives a slightly different version of events. In both accounts, King Mesha is portrayed as a rebellious vassal of the king of Israel. In the Bible, the Israelites successfully attack the Moabites and destroy their towns. In Mesha’s account, however, the Moabites, with the help of their god Chemosh, succeed in their rebellion: According to the stela, “Israel has perished forever.” Despite this discrepancy (and others), the stela was the first archaeological corroboration of events described in the Bible. The public excitement was enormous.

The significance of the find can only be understood in the context of biblical scholarship at the time. The Bible—or at least its literal interpretation—had already come under attack. In the first half of the 19th century, scholars were questioning the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch, the so-called Five Books of Moses, whose death is described at the end of a work he supposedly authored. In his history of Israel (three editions were published between 1843 and 1864), Heinrich Ewald argued that the Pentateuch was an amalgam of five or six separate works. The theory was further refined by another German scholar, Karl Graf, in the 1860s (followed by the still-classic exposition of the 037documentary hypothesis by Julius Wellhausen in the decades that followed).e

In this context, the Mesha Stela was taken as comforting proof that the history related in the Bible was indeed true. The biblical king Mesha was a historical person. There actually were Moabites, and they worshiped an idol named Chemosh. The Mesha Stela, in short, showed the doubters wrong.

It was into this world that Moses Shapira inserted himself. By creating an enormous number of fake Moabite artifacts, he almost single-handedly created Moabite culture and civilization. As Uri Katz has observed, “What differentiates Shapira from other antiquities forgers is his impressive success in generating, purely out of his own creative genius, an entire culture.” With the help of his factotum, Salim al-Kari, Shapira had a well-oiled workshop that produced clumsy fakes—clumsy in the eyes of any modern observer but not so obvious at a time when few authentic antiquities were available for comparison. Based on these fakes, different theories sprang up about Moabite culture that were discussed in both the scholarly and popular press. In the words of Haim Be’er, a contributor to the cataloguef that accompanied a recent Israel Museum exhibit of the Shapira fakes, “It is impossible not to marvel at the man’s 038brilliant ability to capitalize on the heady spin of the international antiquities market during this period and use it to his own advantage.”

The most popular of the Shapira fakes were large human heads—mostly male, though some were female—carved from stone. They have stylized facial features and foreheads that are often decorated with flowers. Archaeologists today know that large stone statues are not part of the cultural context of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. But this information was not available to collectors—or forgers—of the 19th century. In their ignorance, they carved “oriental style” stone heads, appending inscriptions in supposedly ancient Hebrew copied from the script of the Mesha Stela (the Mesha Stela is actually inscribed in Moabite, a language very similar to Hebrew). Shapira even copied the dots that served as word-dividers in the Mesha Stela. Some of the statues Shapira produced were peddled as the heads of the kings of Judah and Israel.

Shapira’s shop also created clay vessels bearing crude inscriptions, which were also copied from the Mesha Stela. These inscriptions, which cover the entire surface of the vessel, have no meaning, even if they occasionally combine to create a string of existing words.

Another category of objects produced by Shapira included clay figurines, often with inscriptions—just like the inscriptions on the clay vessels.

The authenticity of the Shapira collection was in question almost from the beginning. Writing in London’s Athenaeum, Clermont-Ganneau, who was ultimately to be Shapira’s undoing, declared:

My opinion on the subject was formed at the outset, and has never varied. The first papers printed in Germany on the subject of this inscribed pottery produced upon me the immediate impression that it was the work of a forger, while the drawings sent to London, and shown to me, served to confirm this first impression. Nevertheless, my judgment being based on indirect, and, so to speak, personal proofs, I did not think myself justified in pronouncing my opinion publicly … Before the verdict of scientific authority so considerable as that of Germany, I thought it wise to reserve an opinion which might have seemed rash, or even inspired by a sentiment of jealousy or envy.1

The judgment of the German scholars referred to by Clermont-Ganneau is also referred to in a Palestine Exploration Fund report to the British filed 039by a Lieutenant Claude Regnier Conder—an important figure in our story:

The talk of Jerusalem, and of the travellers then crowding in and around it, was the great Shapira collection … The collection has struggled through the first stage of disrepute and incredulity, and the German savans have distinguished this valuable and unique series from the clumsy forgeries so common in Palestine, ranking it with the Moabite Stone.2

Shapira himself defended the authenticity of the pottery collection. He even organized an archaeological expedition to Moab, where pieces resembling those in his collection were actually excavated—though we now know that they had been salted there by Shapira’s Bedouin henchmen.

The Germans, still smarting from losing the race for the Mesha Stela, hurried to acquire Shapira’s Moabite artifacts before they could be sold to the British or French. In 1873 the Berlin Museum acquired from Shapira 1,700 clay objects for the sum of 22,000 thaler (about $235,000 today), a portion of which was donated by the Kaiser himself. The Germans were not the only ones to be taken in. The Englishman Horatio Herbert Kitchener, later to distinguish himself as a military hero at Khartoum, purchased eight “Moabite” pieces from Shapira for the Palestine Exploration Fund.

With the sale to the Berlin Museum, Shapira became not simply a merchant but an expert in antiquities. The sale also enabled him to raise his standard of living. He moved from Jerusalem’s Old City and rented a large lovely house, then known as the Aga Rashid castle, outside the city walls. Along with his Lutheran wife and their two daughters, Shapira lived and worked at Aga Rashid during the latter part of his life. (Today it is known as Ticho House, after the ophthalmologist Albert Ticho and his wife, the artist Ann Ticho, who lived there for many years. Among other things, it is now a museum for the display of her works. Its refreshment garden is a popular refuge for Jerusalemites hoping to escape the stress of city life. In 2000, it was also the venue for an Israel Museum exhibit of Shapira’s Moabite fakes, which are now almost as valuable as actual antiquities.)

Despite this new-found fortune, the authenticity of Shapira’s collection continued to be a matter of intense 040debate. Clermont-Ganneau, for one, would not let the matter rest. He loudly proclaimed that the modern design of the items and the shapes of the letters in the inscriptions proved that they were fakes. From the beginning, Clermont-Ganneau suspected Salim, Shapira’s assistant. The clay in the pottery was identical to the clay used by Jerusalem potters, like Salim, at that time. As Clermont-Ganneau recounted, “Convinced that the pottery was the work of Selim el Gari, and that it was made at Jerusalem, I took measures to surprise him, la main dans le sac.”

First, he found Hassan ibn el Bitar, the Arab from whom Salim bought his clay, who told him how Salim placed letters on the pottery. He also explained that Salim made the vessels look ancient by soaking them, while still hot, in a cauldron of salt water—a “couche of saltpetre which was to be their brevet of authenticity,” in Clermont-Ganneau’s words.

An Arab referred to as Baki signed a statement saying that Salim and his father had commissioned him to “make for them large and small pots, and to take from me clay, and make it into images, and write upon them … They called them ‘Antika,’ and they used to make of it hundreds of different objects.”

At this point, the story begins to have elements of low comedy. A deputation consisting of Clermont-Ganneau, Conder, Charles Tyrwhitt-Drake (another representative of the Palestine Exploration Fund) and a German pastor who had been on Shapira’s “Moabite excavation” questioned Hassan, who stated under oath that Clermont-Ganneau had “locked him up [in Clermont-Ganneau’s house], beaten him, and threatened him with death, to force him to repeat the lesson that [Clermont-Ganneau] had taught him.”

Salim, too, was examined. He testified before the deputation that “M. Ganneau, meeting me two months ago in the street of the Christians, under the Arch, near the Greek convent, told me that he would give me a hundred pounds if I would affirm that the Shapira pottery was false, and was fabricated by Shapira and myself.”

Shapira, of course, defended the authenticity of his pottery:

All the witnesses on whom M. Ganneau relies have been found utterly worthless … [The deputation consisting of] four gentlemen of the highest character, one of whom is an Englishman … have by a severe cross-examination of several days’ duration … not been able to produce the slightest evidence against the genuineness of my collection, nor has the sudden search of Selim, the suspected forger’s house, brought anything to light to warrant the accusation.

Clermont-Ganneau shot back:

The matter … admits of only one way of looking at it:—(1) Either I have devised this black plot. (2) Or these men are either hardened scoundrels, or else poor devils telling their story from fear or interest, and under pressure of the kind that they pretend me to have exercised on them …

We have brought ourselves face to face with a dilemma. Either I am myself an illustrious impostor, or the pseudo-Moabite pottery must be definitely banished from that scientific domain into which it should never have been allowed to enter …

Those who do me the honour of supposing me incapable of the basest, the most odious, and at the same time the most stupid machination, may say with me—habemus confitentem reum [we have the confession of the accused].”

Clearly the pieces were fakes. In the end, even Shapira could no longer defend them. The question, however, remains: Was Shapira a party to the duplicity? Or was he taken in by Salim? Today it seems obvious that he must have known. Yet at the time those who questioned the authenticity of the pieces were careful to absolve Shapira himself and put the blame elsewhere. Even Clermont-Ganneau, at the height of the controversy, blamed Salim: The culprit was “the principal agent employed by M. Shapira … whose good faith, I hasten to say at once, I have no intention of suspecting, and who appears … to be the first dupe, and the accomplice, of this colossal deception.”

Tyrwhitt-Drake, who represented the Palestine Exploration Fund, expressed the same confidence in Shapira’s probity: “The forger proceeded to dupe this energetic collector [Shapira], of whose honesty and good faith in the matter I have no doubt.”

It seems clear, however, that Shapira knew. After all, as an antiquities dealer, Shapira would have recognized the clay used by Jerusalem potters—and, indeed, his career depended on his being able to distinguish a fake from an authentic piece. Then, as now, forgeries were flooding the market and Shapira 041was certainly alert to the possibility.

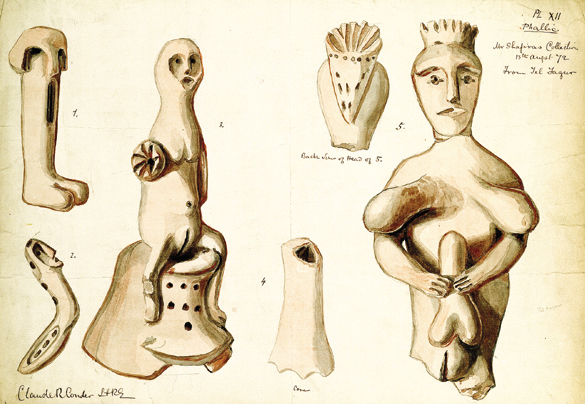

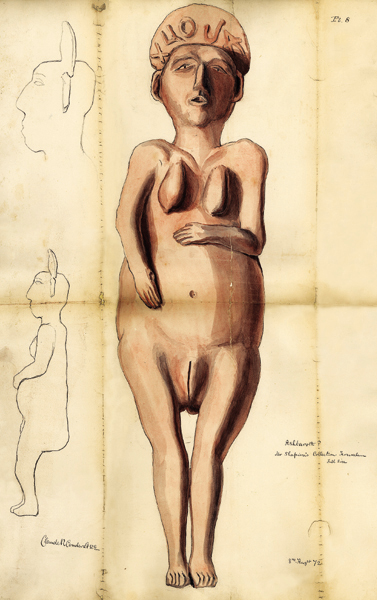

Another mystery concerns the existence of some erotic—or rather pornographic, for they are not at all erotic—fakes that were part of Shapira’s pottery collection. Unlike the rest of the pottery collection, the whereabouts of all of the pornographic pieces is unknown. We have no idea whether some of them still exist in private collections. We know of them only from drawings made by Conder (only one of which was displayed in the recent Jerusalem exhibit of the Shapira fakes) and Tyrwhitt-Drake. These drawings are now in the archives of the Palestine Exploration Fund in London, which has kindly made them available for this article. They portray a number of grotesque genitals, male and female, and figurines with distorted exposed genitals.

Claude Regnier Conder was in fact a talented artist. His paintings of people and places of the Holy Land are quite impressive. Conder arrived in Palestine at age 25 in July 1872 to direct the Palestine Exploration Fund’s survey of western Palestine. In 1874 Conder appointed one of his friends, the 24-year-old Lieutenant Horatio Herbert Kitchener, as his deputy. Conder’s work in Palestine ended in 1875 when he and Kitchener were seriously injured in an attack on the survey by Arabs, but he returned in 1881 to continue working in Transjordan and Syria.

Conder made his drawings of the pornographic pieces in the latter half of 1872, after Shapira had arranged the expedition to Moab to excavate the salted fakes. Whether these pornographic pieces were among the expedition’s finds is not known. In any event, it is clear that Conder (and Tyrwhitt-Drake) believed them to be genuine. His drawings are dated and labeled as part of “Mr. Shapira’s Collection.” The drawings of the pornographic pieces were among more than 200 drawings and watercolors that Conder sent back to London. The drawings were deemed offensive, however, and they were never exhibited.

By 1883 Conder, like everyone else who had vouched for the authenticity of the collection, must have realized that he had been badly duped. Perhaps he, too, thought that Shapira was innocent and had been, like himself, deceived. In any event, when Shapira arrived in London in 1883, Conder, by then the doyen of British archaeology, was a member of the British team that examined the strips for the British Museum. An account of the meeting from the memoirs of the secretary of the Palestine Exploration Fund, Walter Besant, indicates that the meeting lasted “about three hours,” though Shapira had left immediately after unveiling the strips to the excited scholars.

Conder quickly came to the same conclusion regarding the strips as did Clermont-Ganneau, who “condemn[ed] this supposed recension of Deuteronomy as a forgery.”3 For Shapira, this was the final blow. Before departing from London, he wrote a letter to another member of the examination team, Christian David Ginsburg, who was also a convert from Judaism. Ginsburg and Shapira had long worked together in connection with the many Hebrew manuscripts that Ginsburg helped the British Museum acquire from Shapira between 1877 and 1882. Shapira wrote to Ginsburg: “I do not think that I will be able to survive this shame, although I am not yet convinced that the ms is a forgery.”

Exposed once again as a forger, a distraught Shapira committed suicide.

Moses Wilhelm Shapira is best known for the so-called Shapira Strips, narrow fragments of supposedly ancient parchment on which were inscribed a somewhat different version of the Ten Commandments from Deuteronomy than is known from the Bible. Said to have been found in the cliffs east of the Dead Sea, they were written in the ancient Semitic script used before the Babylonian Exile. Shapira sought to sell them to the British Museum for a million pounds. When he arrived in London in 1883, he allowed two of the 15 strips to be 034exhibited to the public. The crowds went […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Siegfried H. Horn, “Why the Moabite Stone Was Blown to Pieces,” BAR 12:03.

The British representative was Captain Charles Warren, an engineer who surveyed the Holy Land on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. The Germans were represented by the Prussian consul J. Heinrich Petermann. Whether Shapira was also involved in the German negotiations is not known.

The remainder of the text has been reconstructed from a squeeze, unfortunately itself in seven pieces, made for Clermont-Ganneau by a certain Ya’qub Karavaca (see Horn, “Moabite Stone”).

According to the documentary hypothesis, the first five books of the Bible (the Torah or Pentateuch) consist of at least four discrete textual strands, labeled with the letters J, E, P, D. In strand J, God is referred to as “Yahweh” (or “Jahweh” in German), while in E, God is referred to as “Elohim.” P, which stands for Priestly Code, makes up much of Leviticus, and D, or Deuteronomist, largely consists of the Book of Deuteronomy.

See Truly Fake: Moses Wilhelm Shapira, Master Forger (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2000). The following description of the fakes is taken largely from the essay by Irit Salmon, “The Life and Times of Moses Wilhelm Shapira,” in the catalogue. Ms. Salmon, who was also the curator of the exhibition held in the summer of 2000 at Ticho House, in Jerusalem, has graciously reviewed the manuscript. The responsibility for all errors, of course, is the author’s.