Ossuary Update

Final Blow to IAA Report

Flawed Geochemistry Used to Condemn James Inscription

038

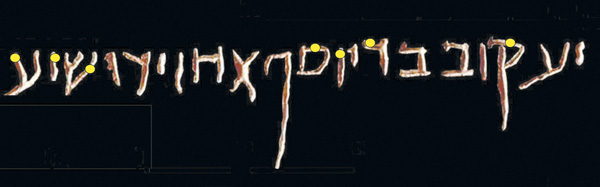

Sorbonne paleographer André Lemaire recently analyzed in these pages the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) report that declared the James ossuary inscription (“James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”) to be a modern forgery.a Lemaire considered various aspects of the IAA report, such as paleography and orthography, and convincingly found the report deeply flawed.

As Lemaire is not a geologist, however, his analysis naturally excluded the part of the IAA report dealing with the geological aspects of the ossuary and its inscription. And, in fact, the individual statements of the committee members clearly show that most of them were driven to their conclusion by the evidence put forward 039by the two scientists on the committee.

I have examined this evidence to the extent that it is available. (Both scientists specifically point out that their statements are not final reports and that they will publish their complete findings later in a professional journal; in the meantime, we can only work with what information is available.) Like Lemaire, I too find the evidence relied on does not support the conclusion that the inscription is a forgery.

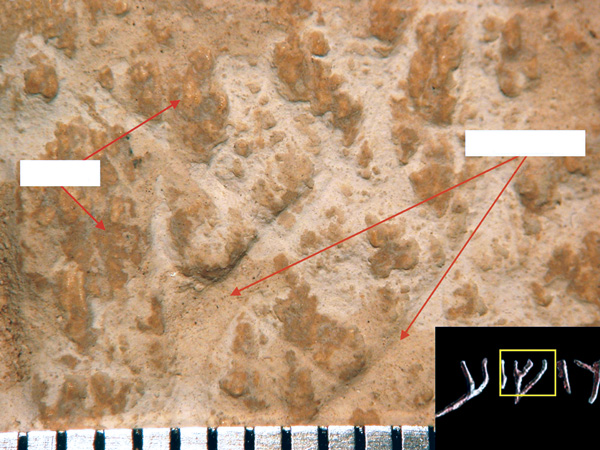

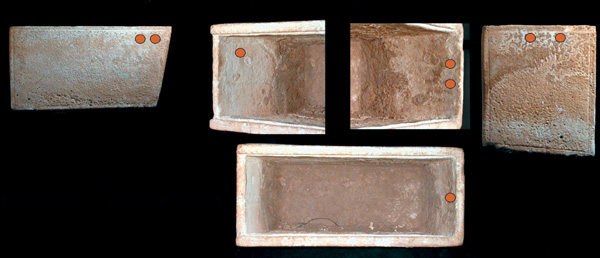

The geological evidence is based on the work of Professor Yuval Goren, a specialist in the microanalysis of archaeological materials at Tel Aviv University, and Dr. Avner Ayalon, a geochemist with the Geological Survey of Israel. Professor Goren reported the presence of a hard, brownish patina that occurs on all parts of the ossuary. He and others acknowledge that both this patina and the ossuary itself are ancient. Goren also identified an anomalous, soft, grayish coating found only within and immediately around the ossuary inscription. Dr. Ayalon performed an isotopic analysis of this inscription coating and also of the brownish ancient patina, and found that the former “could not have formed naturally in conditions of temperature and typical water composition in the Judean Hills in the last 2,000 years.” This conclusion was the basis of the committee’s finding that the inscription was a forgery, although Ayalon himself did not use the term “fake” or “forgery” in his statement.

To understand the geological argument requires a short introduction to the geochemistry of oxygen isotopes. The primary constituent of the limestone that the James ossuary is carved from is the mineral calcite (CaCO3). As the formula indicates, oxygen is one of the elements in calcite, along with calcium and carbon. Ayalon assumed (but did not demonstrate) that calcite is the primary, if not the only, mineral in both the ancient patina and the inscription coating. The analysis of oxygen atoms in the calcite formed the basis of Ayalon’s results.

There are three different kinds of oxygen atoms, which geochemists call oxygen-16 (16O), oxygen-17 (17O) and oxygen-18 (18O). These are the three isotopes of oxygen. The numbers refer to their atomic mass, which is the number of protons in their nucleus (8) plus the number of neutrons (either 8, 9 or 10; see sidebar).

All three isotopes are found in every substance containing oxygen. Oxygen-16 is by far the most abundant isotope and is also the lightest. Oxygen-18 is the second most common isotope and is the heaviest.

In oxygen isotope studies, geochemists measure the ratio of the two most abundant isotopes (18O/16O) in 040samples. This is combined in a formula with the 18O/16O ratio of a standard (with known, fixed amounts of 18O and 16O) to calculate a value called “delta oxygen-18, ” or simply, “d18O,” which is expressed in units of parts per thousand (also referred to as “per mil”). As the amount of 18O in a sample decreases relative to 16O, the d18O value decreases (becomes more negative).

Ayalon first sampled the patinas of three other ancient limestone ossuaries from the Jerusalem area (provided to him by the IAA; he assumed them to be representative) to give him a standard for comparison purposes. These produced d18O values between –4 and –5. Nearly the same d18O values (–4 to –6) are observed for patinas forming on natural limestone outcrops near Jerusalem.

Ayalon compared these results with eight samples of brownish patina on the non-inscriptional parts of the James ossuary. These had similar d18O values of –4 to –6 and thus confirm the patina’s antiquity.

He then took seven samples of the grayish coating from different letters of the inscription. All but one of these samples produced d18O values between –7.5 and –10.2. These results are markedly different from those for the ancient patinas on the James and other ossuaries.

The seventh sample of inscription coating, however, produced a d18O of –5.8. This was clearly within the range of results for the ancient patina on the James ossuary (–4 to –6).

What is the significance of these results? Assuming the ancient patinas and inscription coating consist only of calcite that crystallized in water typical of the Jerusalem area, then the more negative the d18O value, the higher the water temperature.

Given the d18O values for the natural ancient patina on the James ossuary as well as one sample of the inscription coating (–4 to –6), the temperature of the water, as calculated by Ayalon, would be between 64 and 68 degrees F. For the other six samples of inscription coating, the d18O values of –7.5 to –10.2 indicate that the calcite crystallized in water of up to 122 degrees F.

Since, Ayalon says, water temperature up to 122 degrees F does not occur in the Jerusalem area, the inscription coating was not created by natural processes over the past 2,000 years. Given this, he concluded that the inscription coating is artificial and therefore modern. He also concluded that the inscription itself, because of its close association with the coating, must also be modern.

How then was this inscription coating made? Ayalon suggests the following: First, limestone, possibly from the James ossuary itself, was ground to a powder and dissolved in hot water. Second, the hot paste so 041produced was smeared over the inscription. The purpose of the hot water, he says, was to insure good adhesion of the coating.

Ayalon also suggests an alternative scenario: A cold, wet paste of ground limestone was smeared over the inscription and the entire ossuary was then warmed in an oven.

It is clear from the statements of IAA committee members that they were strongly influenced by Ayalon’s conclusions. This is unfortunate because there are three serious flaws in his reasoning:

First, ground calcite will not dissolve in hot water.

Second, undissolved calcite immersed in hot water will not exchange oxygen isotopes with the water and so will not have a d18O value reflecting the water’s temperature.

Third, heating calcite in an oven will not change its d18O value.

Ayalon’s interpretation is therefore based on flawed chemistry.

For Ayalon’s hot-water scheme to work, the limestone would have to be dissolved in a hot acid-water solution and then the calcite crystallized by evaporating the solution. However, a coating made in this way would have an acid residue and so give away its origin. To test for this possibility, the inscription coating needs to be chemically analyzed, but this has not yet been done.

There is yet another reason why we should not trust Ayalon’s interpretation. He implicitly assumes that both the ancient patina and inscription coating are pure calcite. However, if the actual compositions are even a little different, the d18O values will have a different meaning; that is, they will reflect variations in composition as well as temperature. The ancient patina is clearly not pure calcite—its brownish color must be due to either iron oxides, clay minerals and/or organic matter, all of which contain oxygen. The inscription coating also may not be pure calcite.

The conclusion to be drawn from Ayalon’s misinterpretation of his own data is that something else is causing the inscription coating to have very negative d18O values. If it is not temperature, it must be some chemical residue from another substance. It could have been produced either by a fake patina or by some cleaning product. Interestingly enough, Goren recognizes this by stating, as Lemaire pointed out, that “the inscription was engraved (or at least, completely cleaned) in modern times.”

One other point: Ayalon dismisses out of hand the one sample of inscription coating whose d18O value fell within the range of the ancient patina. He disregards this result because he attributes it to an accidental mixing of the ossuary limestone (with a d18O of +1 to –2) and the inscription coating, resulting in an intermediate d18O value. He may be correct in this, but he is showing his bias by not allowing for the other possibility: that the word Jesus (where the sample came from) is truly ancient. This, plus the fact that one member of the IAA committee observed traces of ancient patina in the “brother of Jesus” part of the inscription, provide two solid pieces of evidence supporting the inscription’s antiquity.

On any additional testing of the James ossuary, we should naturally do more isotopic analyses to confirm Ayalon’s measurements. More important, however, we should also perform comprehensive chemical and mineralogical analyses on the inscription coating, including carbon isotope, elemental (microprobe) and x-ray diffraction analyses. Thin section petrography would also be helpful, but unfortunately this would require destruction of small fragments taken from the inscription. Oxygen isotope analyses of other limestone ossuaries from the Jerusalem area are also desirable to better establish the normal range of d18O values for natural patinas.

Finally, we should also conduct experiments to reproduce the physical and chemical characteristics of the inscription coating. Only through experiments will the origin of the coating be known with a high degree of certainty.

For the moment, all we can say is that the oxygen isotope results are equally consistent with two possible interpretations:

1. The inscription is a modern forgery that was coated with a faked patina; OR

2. The inscription is ancient but was cleaned in modern times with the coating produced either inadvertently as a result of cleaning or intentionally to disguise the cleaning.

The IAA’s acceptance of the first possibility above is not required by the currently available data.

Sorbonne paleographer André Lemaire recently analyzed in these pages the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) report that declared the James ossuary inscription (“James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”) to be a modern forgery.a Lemaire considered various aspects of the IAA report, such as paleography and orthography, and convincingly found the report deeply flawed. As Lemaire is not a geologist, however, his analysis naturally excluded the part of the IAA report dealing with the geological aspects of the ossuary and its inscription. And, in fact, the individual statements of the committee members clearly show that most of them were driven […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

“Ossuary Update; Israel Antiquities Authority’s Report on the James Ossuary Deeply Flawed,” BAR, November/December 2003.