The search for the historical patriarchs of Genesis has taken some dizzying turns in the last half-century. From the 1940s through the 1960s, scholars proclaimed that the patriarchal age of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph had been found among the mass of new archaeological data recovered from the second millennium B.C.E. In the 1970s and 1980s, the tide turned, and the patriarchal age was lost again, as the arguments of the previous decades were shown to be over-interpretations of the data, compounded with wishful thinking. Nowadays the patriarchs, for many scholars, are no more than a “glorified mirage” concocted by the Pentateuchal writers, as Julius Wellhausen argued over a century ago.1

Turning against this tide of minimalism, Kenneth Kitchen boldly argues in the March/April BARa that the maximalist position can be maintained,b indeed strengthened, on the basis of our current understanding of the Bible and of the ancient Near Eastern data. While Kitchen agrees that the criticisms advanced during the 1970s by John Van Seters,2 Thomas Thompson,3 Donald Redford4 and others were appropriate, and that faulty comparisons and arguments had been made by earlier scholars, he maintains that a re-examination of the data supports the existence of the patriarchal age in the first half of the second millennium B.C.E., the period archaeologists call the Middle Bronze Age. Kitchen pursues his task with characteristic erudition, apparently demonstrating that the facts and the Bible match up in a number of different areas.

Is Kitchen right? Are the minimalists proven wrong? Since this is such an important issue for students of the Bible, I believe that a careful consideration of Kitchen’s arguments is in order. I mean no disrespect to Professor Kitchen in subjecting his arguments to examination—in fact, quite the reverse. I believe that Kitchen has constructed as strong a case for the maximalist position as can be made at the present time. If his position withstands close examination, then it should be accepted. If it has flaws, then these need to be shown. Such is the process of historical scholarship—a conversation over the facts and over how to understand them.

In the sidebar “Dating the Patriarchal Age: Where Kitchen Erred,” I outline some of the flaws in Kitchen’s arguments. To summarize, his arguments simply do not work. In each instance the relationship between the Biblical texts and the extra-Biblical data is sufficiently loose that no historical conclusions can be drawn concerning a patriarchal era. If my criticisms are sound, are we then left with the minimalists’ claim that the patriarchs are a “glorified mirage” concocted by the Pentateuchal writers? I think not—because the minimalists are wrong, too. Among the wreckage of past scholarship there are bits of data and historical arguments that show the antiquity of at least some aspects of the patriarchal traditions.

I will try to untangle and refine the best of these arguments to show that some patriarchal traditions clearly predate the major Biblical writings concerning the patriarchs (J, E and P),c and that some traditions clearly predate the formation of Israel in about the 12th century B.C.E. (Iron Age I). First let me clarify the nature of this historical task. I am not trying to prove or disprove the patriarchal narratives the Bible presents in Genesis 12–50. Rather, I am trying to clarify the relationship between the patriarchal narratives and ancient Near Eastern history. In this relationship we are not limited to the simple contrast between true and false, history and fiction. The actual relationship is somewhere between the two, where history and imagination intermingle. In my understanding of the text and the historical facts, the patriarchal narratives of Genesis are a composite of historical memory, traditional folklore and narrative brilliance. To inquire into the historical memory in the stories is to address something other than their folklore or literary art. Yet each of these dimensions of the patriarchal narratives—the historical, the folkloric and the literary—is needed to appreciate and understand the whole. When we address historical questions we need to realize that we are, at least for a time, neglecting the other dimensions of the text, and that a full investigation will bring all the dimensions together. History is necessary, but it is not sufficient; it is only the first step toward a modern understanding and appreciation of the patriarchal narratives.

Having indicated the limitations of our historical inquiry, we may ask what is to be gained by such an inquiry. If we can find clear indications of historical memories of events or milieux that antedate the Biblical writers, then we have falsified the basic claim of the minimalists that everything is late and fictional. If we find clear evidence that these stories preserve at least traces of ancient traditions, then we can better understand the nature of the historical element in Israelite culture. We gain insights into the relationship between tradition and writer in the creation of Biblical texts. We can even better appreciate the ways in which the Biblical stories, as a common inheritance, articulated a national, religious and ethnic identity for the Israelites. We may also better perceive the sacral quality of the stories, as directly relating to the religious life of the people.

But do we find the historical patriarchs or the patriarchal era? I don’t think so. In the present state of the evidence, historical arguments bear only on the underlying nature of the patriarchal stories and traditions. We still have no clear evidence concerning the original Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph or the rest of the cast of Genesis. We do not know when or if any of these characters ever existed. All we can say is that traditions concerning these figures existed long after the figures themselves were supposed to have lived and that we can date some of these traditions.

But let me first make one other important point: Even if a historical Abraham did exist and we could verify his existence, this fact would not solve any other of the historical questions of the patriarchal stories. We still would not know if the historical Abraham did any of the things recounted in the stories. This is a common situation in narrative traditions: even when the protagonist is historical, as with Gilgamesh, King Arthur or George Washington, this fact doesn’t tell us whether the story is historically true or preserves authentic historical memories. The story of George Washington and the cherry tree is a classic American example (historians say it never happened). The same caution must extend to the Biblical patriarchs.

If we cannot find the patriarchs or the patriarchal era, then let us try to find at least the patriarchal traditions in history. Do they predate the major Biblical writers? Do they predate the era of Israelite society (beginning in about 1200 B.C.E.)? How can we tell?

Three bodies of evidence show that some aspects of the traditions are old, extending in some instances to the mid-second millennium B.C.E. This is not to say that all aspects of the tradition are that old. The patriarchal stories, as with other narrative traditions, consist of elements of varying antiquity. The minimalists have emphasized the late elements. Let us consider the more ancient ones.

In about 925 B.C.E., the Egyptian Pharaoh Sheshonq I (Biblical Shishak) mounted a military expedition into the recently divided states of Judah and Israel that replaced the United Monarchy. Sensing a moment of weakness, Sheshonq’s forces devastated the land. The Biblical accounts only begin to suggest the extent of the destruction:

In the fifth year of King Rehoboam, King Shishak of Egypt marched against Jerusalem. He carried off the treasures of the House of Yahweh and the treasures of the royal palace; he carried off everything. He even carried off all the golden shields that Solomon had made.

1 Kings 14:25–26

According to the fuller account in 2 Chronicles 12:2–12, Shishak’s invading army had 1,200 chariots, 60,000 horsemen and innumerable troops. They “captured the fortified towns of Judah and advanced on Jerusalem,” where Rehoboam apparently averted disaster by giving Shishak the Temple treasury.

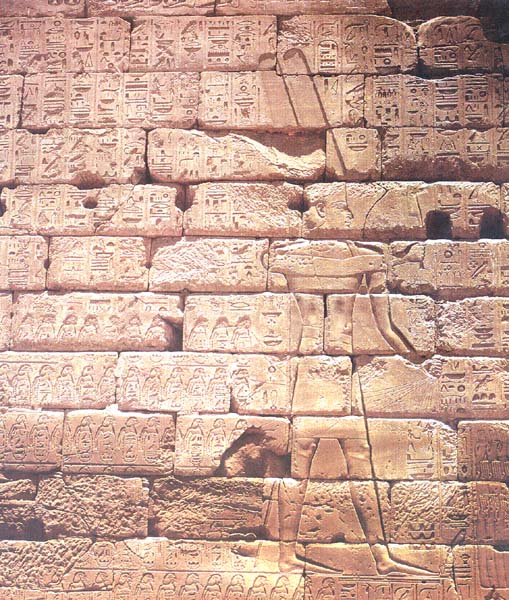

Upon his triumphant return to Egypt, Sheshonq had a victory stela carved into a wall of the Temple of Amun in the city of Karnak.5 On this stela were carved the names of perhaps 150 sites (many now eroded or illegible) in Judah and Israel that Sheshonq’s army conquered. Roughly 70 of these sites are in the Negev. One of these Negev sites is called, in Egyptian syllabic writing:

The first Egyptian sign in this place-name is “the”; the word that follows means either “fort, fortified” (from Hebrew

Who is the Abram of Fort Abram? There are two possibilities. Either it is the Abram famous from the Biblical stories of the patriarchs,e or it is another Abram whom we have never heard of. The minimalists prefer the second option. For example, John Van Seters, in his important book Abraham in History and Tradition, notes the existence of the name Abram in this tenth-century B.C.E. place-name, but argues: “There is no reason to suspect that the name has any connection with the patriarch.”8 This is a possible position. But is it plausible? Let us consider the other possibility, that Fort Abram was named after the patriarch Abram. Are there any reasons to prefer this possibility? The answer is yes.

Geography. The place-name Fort Abram is found on Sheshonq’s list of sites in the Negev. The Biblical Abram lived in the Negev and southern Judah. Therefore, Fort Abram was located in a region that the Bible associates with the patriarch Abram.

Chronology. Fort Abram existed in the tenth century B.C.E., shortly after the United Monarchy divided following the death of Solomon. The site probably existed during the United Monarchy. Numerous scholars have found indications in the Bible of Davidic-Solomonic ideology in the stories of Abram, such as Yahweh’s unconditional promises—of land, descendants and greatness—to Abram (Genesis 12:1–3; 13:14–17; 15 et al.) and David (2 Samuel 7:8–16; Psalm 89:4, 29–37).9 It makes sense that a fortified site in the Negev, probably during the United Monarchy, would be named by royal officials after the father of the nation, whose stature would glorify the Davidic king.

Archaeology. Excavations in the Negev have revealed a high density of sites during the tenth century, in accord with the numerous Negev sites listed in Sheshonq’s stela.10 Only a few sites can be clearly identified with place-names in Sheshonq’s list, such as Arad, which in the stela is called “The Fort of Great Arad.” Most of these Negev sites were fortified by casemate walls enclosing the area, hence the probable sense of the word

A further possible argument under the heading of archaeology was suggested by Yohanan Aharoni, the excavator of Arad, Beersheba and other Negev sites. Aharoni noted that Arad is mentioned in Sheshonq’s list, but Beersheba is not. This omission is strange, since Beersheba was a prominent site in the region at the time. He suggested, therefore, that Fort Abram was the term the Egyptians used to refer to Beersheba.11 In Biblical traditions Beersheba was founded by Abraham (see Genesis 21:22–33), so the identification of Fort Abram with the unlisted site of Beersheba is a very real possibility.

All this leads us to think that the tenth-century B.C.E. Negev site called Fort Abram was named for the patriarch Abram. The place is right, the time is right, the political setting is right, and the archaeological data from the region are right. True, we cannot prove that Fort Abram is testimony to the traditions of Abram. But it is a reasonable historical argument that simply and elegantly explains the facts. If we weigh the reasons for and against, the identification of Fort Abram with Biblical Abram is extremely probable. In this case, we seem to have good extra-Biblical evidence for the vitality of ancient traditions of Abram in the tenth century B.C.E.

Two other sets of evidence, both consisting of names, take us back before the tenth century B.C.E., to the period preceding Israel’s emergence as a nation or people.

The first body of evidence consists of the patriarchal names in Genesis in the aggregate. The important point to note is the absence of the divine name Yahweh as an element in any of these names. Commonly, ancient Semitic names were compounded with the name of a god. But in Genesis the only god-name found in personal names is El (for example, Ishmael, Israel, Bethuel)—never Yahweh. Names compounded with Yahweh are not found until Exodus (Joshua [Yehoshua], Jochebed [with a “Y” in Hebrew; Moses’ mother]). This is a striking difference that deserves an explanation.

The great early 20th-century German scholar Albrecht Alt suggested that the absence of Yahweh-names in the patriarchal narratives indicates a pre-Yahwistic origin for the patriarchal traditions.12 Not a bad argument, but I would go even further. As earlier noted, the patriarchal narratives, according to the documentary hypothesis, consist of three authorial strands, designated J, E and P, with the earliest strand being the J (Yahwist or, in German, Jahwist) source. For E (Elohist source) and P (Priestly source), we should not be surprised at the absence of Yahweh-names, since according to these sources the name Yahweh was not known to the patriarchs. But in Genesis, there are no Yahweh-names at all, not even in J.f This directly contradicts J’s view that Yahweh was indeed known to the patriarchs. Therefore, we must ask why there is no Yahweh-name in J’s Genesis narrative. It must be because, in fact, there weren’t any in the tradition that J inherited.

Let me unpack this argument a bit: In both E and P, the patriarchs call their god El or Elohim (with various titles or epithets). In both sources the name Yahweh is first revealed only in the time of Moses (see Exodus 3 [E]; Exodus 6 [P]). Therefore, it is consistent with the views of E and P that the patriarchal names not be compounded with Yahweh. If some patriarchal names had actually been Yahweh-names, E and P might have changed these names to fit their theory, so it is not surprising that we find no Yahweh-names in E and P.

But J holds a different theory. According to the J narrative, the name Yahweh was known from the time of Enosh, son of Seth (Genesis 4:26), and was known to all the patriarchs. So why are there no Yahweh-names in the J narrative in Genesis? The fact that the patriarchal names exclude the divine name Yahweh contradicts J’s understanding of the history of the divine name; for J to list El-names but no Yahweh-names goes against the writer’s own intentions. Unlike the case with E and P, there can be no question of J’s manufacturing patriarchal names to delete the Yahweh-element. What J doesn’t seem to realize is that the absence of Yahweh in the patriarchal names seems to falsify his theory that the patriarchs called their God Yahweh.

In light of this problem in J, the absence of Yahweh-names from the patriarchal names in Genesis is evidence of the validity, or at least antiquity, of the theory shared by E and P, that the patriarchs did not call their God Yahweh. According to E and P, the patriarchal God was called El—which is corroborated by the evidence of names in Genesis.

This analysis of the Biblical evidence correlates with the historical and archaeological data from Canaanite religion and culture of the pre-Israelite period. The evidence, from Ugarit in the north to Sinai in the south, testifies that during the second millennium B.C.E. the high god of various local Canaanite pantheons was named El.13

Accordingly, the implication of the patriarchal names is historically accurate: The tradition accurately remembered (as evidenced by the names in the patriarchal narratives) that there was a period sometime in the second millennium B.C.E. when there was an El religion. The people who venerated El apparently later became part of Israel (another El-name). In other words, the El religion of the patriarchs preserves authentic pre-Yahwistic historical memories.14

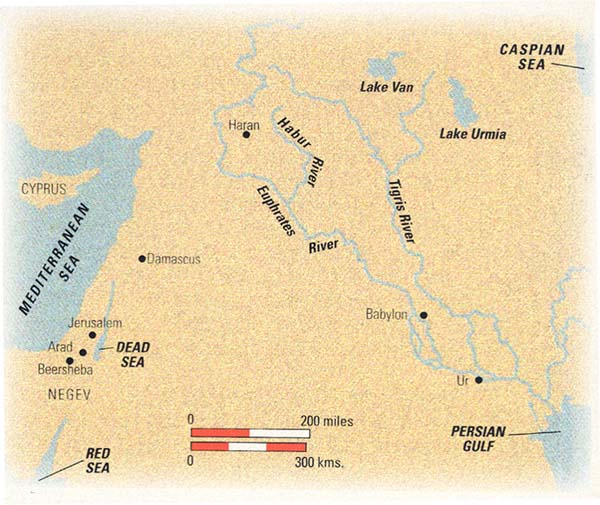

The next body of evidence that takes us to the pre-Israelite period consists of the names of Abram’s close kin and the place they settle. As scholars have long noted, there is a durable link between Abram’s kin and the region of Syro-Mesopotamia between the Euphrates and Habur rivers15 Abram’s great-grandfather is named Serug. His grandfather is named Nahor (as is his brother). His father is named Terah. All of these personal names correspond with place-names in the Euphrates-Habur region of Syro-Mesopotamia. As place-names, they are known in various forms from texts of the second and first millennia B.C.E. Tell (

Haran (H

Even the name Abrum, listed in Old Assyrian texts, is a place somewhere around this area, though its precise location is uncertain.18 These extra-Biblical place-names seem to agree with the Biblical evidence in associating Abram’s lineage with this region of Syro-Mesopotamia. Why?

The historical answer to this geographical linkage is far from clear. The problem is that during the Israelite period this area was Aramean. In Genesis this region is identified as Aramean by the terms Aram-Naharaim (“Aram of the two rivers,” Genesis 24:10 [J]) and Paddan-Aram (“Plain of Aram,” Genesis 28:6–7 [P]). But as the Biblical text amply testifies, the Arameans were enemies of the Israelites from the time of David.19 Why would this be the ancestral homeland if it is the home of enemies after the 11th century?

Yet this is the ancestral region where Abraham’s kin live, where Abraham sends for a wife for Isaac, where Rebekah instructs Jacob to flee and where Jacob marries. These marriages, in kinship terms, are endogamous (literally, “marriage within”) alliances within the patriarchal lineage. The importance of kinship ties in the patriarchal narratives is clear. Elsewhere in the Bible this region is also tied to the patriarchs, as in the famous prayer beginning “My father was a wandering (or perishing) Aramean” (Deuteronomy 26:5).20 But why would the patriarchs be identified with the hated Arameans if the geographical link were not historically accurate?

The only plausible solution to this problem is to look at the Bronze Age of the second millennium B.C.E., when this region was not Aramean but Amorite. It is entirely possible, some scholars have argued, that there is a historical connection between the patriarchal traditions and the Amorite culture of Syro-Mesopotamia during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages.21 As we can gather from the cuneiform texts recovered from Mari and Terqa, Amorite culture was primarily non-urban and tribal.22 The language they used was an early form of Northwest Semitic, the language group that includes Hebrew. A number of cultural traits common to the Amorite tribes and the later Israelite tribes have been noted, including numerous social forms and religious customs.23 The key point is that the region around Haran and the upper Euphrates was part of the Amorite heartland in this period. This is the place so strongly associated with Abram’s lineage.

It seems likely then, that the names of Abram’s lineage and the geographical location of the patriarchal home refer to the Amorite homeland in this area during the second millennium B.C.E. Why does the Bible identify this area as Aramean? Because it was Aramean during the time of the nation of Israel. In other words, the patriarchal traditions were updated to reflect then-current geographical and ethnic realities (even though these revisions introduced a problem), tracing the patriarchal origins to the hated Arameans. The patriarchs became “wandering” Arameans because the ancestral land was now Aramean. But we know that the original ethnic identity of this region was Amorite. In other words, the Biblical terms identifying the ethnic affiliation of this area as Aramean are a first-millennium updating of a second-millennium tradition.24

In this understanding of the facts, the confession “My father was a wandering (or perishing) Aramean” makes sense, as do the patrilineal marriages in Syro-Mesopotamia. It is the Aramean dress that makes the references confusing and problematic.25 If these references were modernizations of ancient memories of the Amorite homeland, then the problems disappear. In short, the Biblical authors who traced the lineage of the patriarchs to the Syro-Mesopotamian heartland appear to have drawn on an historically authentic tradition. I do not mean to suggest that we have made our case beyond a reasonable doubt; but the facts do cohere best with this understanding, and some long-standing problems are resolved. As a historical theory, it has scope and simplicity, and it fits the facts.

So what’s in a name? In the case of the patriarchal traditions, the names of certain persons and places provide the best evidence for tracing the historical roots of the patriarchal traditions. Fort Abram in the Negev of the tenth century is good evidence for the power of tradition already at that time. The absence of Yahweh in the patriarchal names in Genesis, even in the J narrative, indicates a second millennium date for at least some features of the patriarchal worship of the god El. The geographical references in the lineage of Abram and the other references to the patriarchal homeland in Syro-Mesopotamia preserve traces of Amorite kinship bonds from the mid-second millennium B.C.E. These are the best clues we have for the history and origins of the patriarchal traditions.

Is it plausible that the patriarchal narratives, written down probably no earlier than the ninth or eighth centuries B.C.E. (the probable time of J), could preserve memories of pre-Yahwistic religion? Is it plausible that they recall the kinship ties of at least some early Israelites to the old Amorite homeland in Syro-Mesopotamia? This is another matter that the minimalists would dispute, claiming that oral tradition can preserve historical memories no longer than 150 years.26 Is it possible that some memories in the patriarchal narratives are over 500 years old?

The answer is yes. A striking example illustrating the potential memory of oral tradition is found in Amos 9:7, as Abraham Malamat has astutely noted.27 Amos states that Yahweh brought the Israelites out of Egypt, just has he brought the Philistines from Caphtor (Crete and the Aegean region) and the Arameans from Qir (probably in the Middle Euphrates region).28 Extensive archaeological evidence demonstrates that for the Philistines this historical memory is accurate.g In the early 12th century B.C.E., the Philistines did arrive from the Aegean region. This accurate historical memory was 400 years old at the time Amos recited it. A century and a half later Jeremiah also recalled this tradition of Philistine origins (Jeremiah 47:4). This is a good Biblical parallel for the occasional longevity of historical memory in oral traditions. Similar examples from other cultures are numerous.29

Our conclusion is that the Biblical traditions of the patriarchs do carry some ancient memories, stretching back to pre-Israelite times in the second millennium. From these ancient roots, the patriarchal stories grew and changed, were adapted and embellished by storytellers of each age, until they came to be written in brilliant form by the Biblical authors. We can perceive the antiquity of these traditions only occasionally, but the power and authority of the past pervades the stories.

What, then, is the patriarchal era? In the most obvious sense it is the time forever recreated in the Biblical narratives of Genesis 12–50. This era consists of memory and myth, mingled in a way far more compelling than ordinary history. It is an era in sacred time.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Kenneth A. Kitchen, “The Patriarchal Age: Myth or History?” BAR 21:02. See also his Ancient Orient and Old Testament (Chicago: InterVarsity Press, 1966), pp. 41–56; The Bible in Its World (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1978), pp. 56–74; and “Genesis 12–50 in the Near Eastern World,” in R. S. Hess, P. E. Satterthwaite and G. J. Wenham, eds., He Swore an Oath: Biblical Themes from Genesis 12–50 (Cambridge: Tyndale House, 1993), pp. 67–92.

On the use of the terms “minimalist” and “maximalist,” see James K. Hoffmeier in Queries & Comments, BAR 21:02.

Modern critical scholars have divided the Pentateuch into four authorial strands, designated J (the Yahwist or, in German, Jahwist source), E (the Elohist source), P (the Priestly source) and D (the Deuteronomist source, whose contribution to the Pentateuch is confined to Deuteronomy). The narratives of J, P and E are intertwined in the first four books of the Bible.

Compare the variations of Abner (1 Samuel 14:51 et al.) with Abiner (1 Samuel 14:50), and of Abshalom (2 Chronicles 11:20–21) with Abishalom (1 Kings 15:2, 10).

In Genesis 17:5, God changes Abram’s name to Abraham; in origin, these two names are probably dialectal variations from different regions of Israel.

In J’s narrative, although the patriarchs address God as “Yahweh” (rather than “Elohim,” as in E and P), their names do not incorporate the name Yahweh.

See the following articles in BAR: Trude Dothan, “Ekron of the Philistines, Part 1: Where They Came From, How They Settled Down and the Place They Worshiped In,” BAR 16:01; Lawrence Stager, “When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR 17:02; Itamar Singer, “How Did the Philistines Enter Canaan? A Rejoinder,” BAR 18:06.

Endnotes

Anthony Giddens, Social Theory and Modern Sociology (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1987), p. 357. Recent research on this topic is summarized and assessed in Gordon Wenham, Genesis 16–50, Word Biblical Commentary 2 (Dallas: Word Books, 1994), pp. xx–xxviii; the best recent study is P. Kyle McCarter,

See Thomas L. Thompson, The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1927).

On the Shishak stela, see Kenneth A. Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 B.C.) (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1986), pp. 294–300, 432–447; Benjamin Mazar, The Early Biblical Period: Historical Studies (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1986), pp. 139–50; and Yohanan Aharoni, The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1979), pp. 323–330.

James E. Hoch, Semitic Words in Egyptian Texts of the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period (Princeton: Princeton Univ.), pp. 18, 205, 235–237, 568.

See, recently, Moshe Weinfeld, The Promise of the Land (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), pp. 222–264.

See Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, 10,000–586 B.C.E. (New York: Doubleday, 1990), pp. 390–397.

This point is stressed by Albrecht Alt, “The God of the Fathers,” in Alt, Essays on Old Testament History and Religion (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968; German original 1929), p. 7.

See Frank M. Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel (Cambridge: Harvard Univ., 1973), pp. 1–75; and John Day, “Ugarit and the Bible: Do They Presuppose the Same Canaanite Mythology and Religion?” in G.J. Brooke, A.H.W. Curtis, and J.F. Healey, eds., Ugarit and the Bible: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Ugarit and the Bible (Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 1994), pp. 35–52.

For other archaic aspects of patriarchal religion, see Cross, Canaanite Myth, pp. 1–75, 177–186. Compare the minimalist position of John Van Seters, “The Religion of the Patriarchs in Genesis,” Biblica 61 (1980), pp. 220–233; and Rainer Albertz, A History of Israelite Religion in the Old Testament Period, vol. 1 (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 1994), pp. 28–29.

In referring to this region as Syro-Mesopotamia, I follow Giorgio Buccellati’s emphasis that during the Bronze Age there was a cultural continuum in this region encompassing the rural Syrian steppeland west of the Euphrates (see Buccellati, “The Kingdom and Period of Khana,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 270 [1988], pp. 43–61; see also his article, “From Khana to Laqé: The End of Syro-Mesopotamia,” in O. Tunca, ed., De la Babylonie à la Syrie, en passant par Mari: Mélanges offerts à J.R. Kupper [Liège, 1990], pp. 229–253). For the Biblical data, see the still valuable treatment by Roland de Vaux, The Early History of Israel (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1978), pp. 193–200.)

See Barry J. Beitzel, “The Old Assyrian Caravan Road in the Mari Royal Archives,” in Gordon D. Young, ed., Mari in Retrospect (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1992) pp. 36, 38, 52.

On Aramean-Israelite relations, see Wayne T. Pitard, Ancient Damascus: A Historical Study of the Syrian City-State from Earliest Times Until Its Fall to the Assyrians in 732 B.C.E. (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1987) and his remarks on this issue on p. 86.

See especially J. Tracy Luke, “‘Your Father Was an Amorite’ (Ezek 16:3, 45): An Essay on the Amorite Problem in OT Traditions,” in H.B. Huffmon, F.A. Spina, and A.R.W. Green, eds., The Quest for the Kingdom of God: Studies in Honor of George E. Mendenhall (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1983), pp. 221–237; and William G. Dever, “The Patriarchal Traditions: Palestine in the Second Millennium B.C.E.: The Archaeological Picture,” in J. H. Hayes and J. M. Miller, Israelite and Judaean History (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1977), pp. 102–120.

See Giorgio Buccellati, “The Kingdom and Period of Khana,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 270 (1988), pp. 43–61; see also his article, “From Khana to Laqé: The End of Syro-Mesopotamia,” in O. Tunca, ed., De la Babylonie à la Syrie, en passant par Mari: Mélanges offerts à J.R. Kupper (Liège, 1990), pp. 229–253. In “From Khana to Laqé” (pp. 248–249), Buccellati suggests that the pastoral world of the patriarchal traditions may be a reminiscence—perhaps “an ideological manifesto”—from the “pastoralist revolution” of Khana (Amorite) culture. This is an intriguing possibility.

See Abraham Malamat, Mari and the Early Israelite Experience (Oxford: Oxford Univ., 1989). Malamat identifies these common features as at least typologically relevant for comparison, and possibly historically related to the patriarchal traditions (see pp. 27–30).

The names of the descendants of Nahor in Genesis 22:20–24, including Aram and Chesed (the Chaldeans), are another indication of first-millennium updating; in the case of the Chaldeans, the updating reflects conditions known from the ninth and eighth centuries B.C.E.

Note, for example, the difficulties Van Seters finds in accounting for “this feeling of kinship with the Arameans of Northwestern Mesopotamia” (Abraham in History, p. 34). He appeals, among other things, to the Assyrian mass deportations of Israelites to this region and to the importance of the trade route through Haran during the Neo-Babylonian period as factors encouraging a sense of kinship with Arameans. These factors, however, do not seem adequate to explain the relationship in the Biblical text, as the tentativeness of Van Seters’s discussion seems to acknowledge.

See Patricia G. Kirkpatrick, The Old Testament and Folklore Study (Sheffield, England: Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Press, 1988), pp. 108–114.

Abraham Malamat, “The Proto-History of Israel: A Study in Method,” in C.L. Meyers and M. O’Connor, eds., The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth: Essays in Honor of David Noel Freedman (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1983), p. 306.

A recently published Akkadian text from Late Bronze Age Emar describes king Pilsu-Dagan of Emar as “king of the people of the land of Qiri,” perhaps the land recalled by Amos as the Aramean homeland; for this interpretation, see Ran Zadok, “Elements of Aramean Pre-History,” in Mordechai Cogan and Israel Eph’al, eds., Ah, Assyria … Studies in Assyrian History and Ancient Near Eastern Historiography Presented to Hayim Tadmor (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1991), p. 114.

For example, the reminiscences of Mycenean society in the Homeric epics; see Emily Vermeule, Greece in the Bronze Age (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago, 1972), pp. 309–312. For examples of historical memories preserved for several hundreds of years in African and Eskimo oral traditions, see Jan Vansina, Oral Tradition (Middlesex: Penguin, 1973), p. 209, n. 48.