First “Dead Sea Scroll” Found in Egypt Fifty Years Before Qumran Discoveries

Solomon Schechter presages later Essene scholarship

038

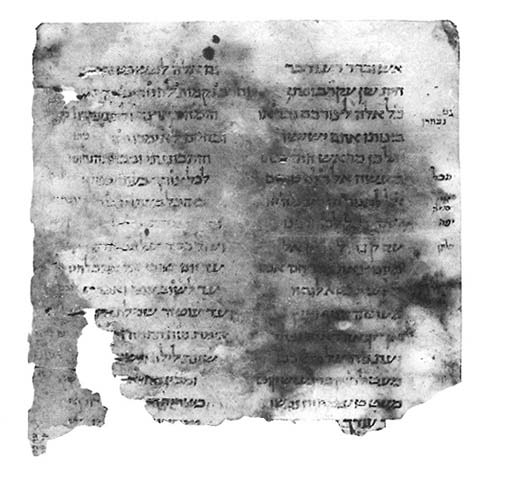

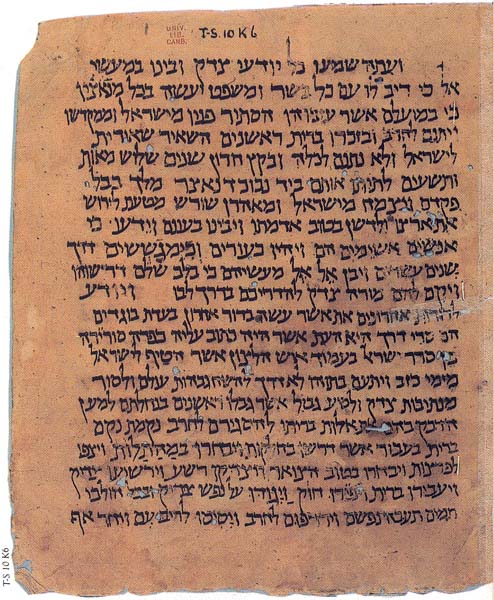

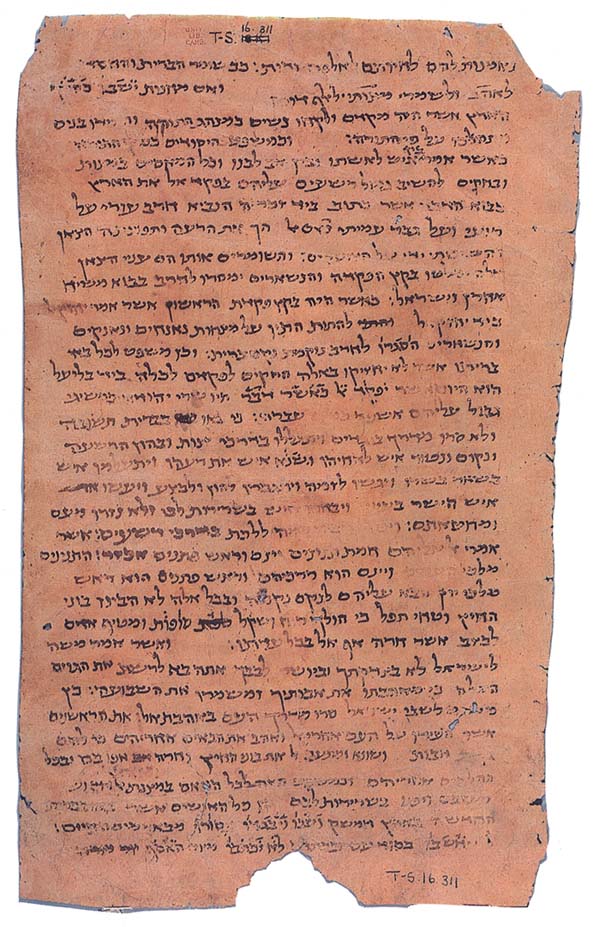

Some call it the first Dead Sea Scroll—but it was found in Cairo and not in a cave. It was recovered in 1897 in a Genizah, a synagogue repository for worn-out copies of sacred writings. The gifted scholar who had found it, Solomon Schechter, gave it with a hoard of other ancient Hebrew manuscripts to Cambridge University, where it still remains today.

Of course no one called it the first Dead Sea Scroll in 1897. That was fifty years before the momentous discovery on the actual Dead Sea Scrolls, in 1947, in the caves of Qumran on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea. The manuscript Schechter received its nickname only after the Dead Sea Scroll scholars realized that it was a copy of a document that belonged to, and described, the sect whose hidden library had been discovered at Qumran.

Today, the “Damascus Document” (or “Zadokite Fragment”), as this Genizah manuscript is known to scholars, is considered to be the most important document in existence for understanding the history of the Essenes, the people who produced and subsequently hid the scrolls in the Qumran caves. And from its tattered pages, Schechter, who never dreamed of Qumran and died before its discovery, was able to give us out first recognizable portrait of the Qumran sect.

The picture he painted was a astonishing one, as was, for a long time, unexplainable. “the annals of Jewish history,” Schechter wrote, “contain no record of a Sect agreeing in all points with the one depicted … ”1

Schechter’s account told of a strange, highly structured and unknown Jewish brotherhood of Second Temple times, given to fierce piety, the communal ownership of property and a belief in a messiah. Their doctrinal differences with established Judaism, he surmised, “led to a complete separation … form the bulk of the Jewish nation.”2

039

Schechter’s report of the brotherhood’s history and laws contained most of the mysterious and intriguing characters, places and events that give the story of the Dead Sea scroll sect its special flavor. In his pioneering study of the Cairo Genizah documenta published in 1910, Schechter told us of the sect’s unknown leader, “The Teacher of Righteousness ,” and his terrible enemy, “The Man of Scoffing.”

He told us also of the sect’s “flight to Damascus” (hence the scholarly designation, “Damascus Document”) to escape persecution at home, and of its adoption there of a “New Covenant.” Finally, he told us that although the Teacher of Righteousness died, the sect believed that by remaining true to his teachings, the Teacher would return as a messiah.

These, of course, are the very personnae and occurrences that have emerged from such Dead Sea Scrolls as the Habakkuk Commentary and the Manual of Discipline. Numerous scholars since Schechter’s time have sought to date and identify the actual people referred to in the Scrolls and to clarify the historical content of the events described. But to Schechter must go the credit for first bringing to the world’s attention this intriguing chapter in our common history.

How Solomon Schechter came to the Cairo Genizah is an exciting story in itself. In 1896, when he set out for Cairo, Schechter was Reader in Talmud and rabbinical literature at Cambridge University. Born in a small Jewish community in Rumania, he showed early brilliance as a student and was sent to a series of yeshivot (rabbinical 040seminaries). Later he went to Vienna and Berlin where he supplemented his rabbinical studies with secular subjects including the new “Judische Wissenschaft,” the scientific study of Jewish history.

In 1882, Claude Goldsmid Montefiore, wealthy scion of two great English-Jewish families, asked Schechter to be his tutor in rabbinics and brought him to London. Schechter was delighted with England and stayed. English Jews enjoyed many freedoms unknown to Jews in Germany, and the famous collections of Hebrew manuscripts and books in the British Museum and the Bodleian Library at Oxford were an additional enticement for Schechter.

In 1890, Schechter was appointed Lecturer in Talmud at Cambridge. By then he had acquired something of a reputation as a scholar and essayist, and at the University his wit and abilities soon brought him warm friends. One of them was Dr. Charles Taylor, mathematician, eminent Christian Hebraist and Master of St. John’s College.

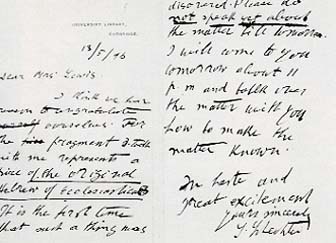

Then two remarkable women entered the story: Mrs. Agnes Smith Lewis and Mrs. Margaret Dunlop Gibson, twin sisters who were “incredibly learned … unbelievably eccentric … and wholly inseparable.”3 Both women were wealthy Scottish widows who were devoted to Biblical scholarship, travel and the collection of early manuscripts. Other Victorian women might stay at home as they were expected to, but the “Giblews” had already made three daring trips on camels from Cairo to St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mt. Sinai to study and photograph the ancient writings in the library there. In May 1896 they returned to Cambridge from yet another Near Eastern trip, this time to Palestine and Egypt. There they had purchased ancient leaves of Hebrew writings which they asked Schechter to examine.

To his astonishment, Schechter recognized one leaf as part of the long-lost Hebrew text of the Book of Ben Sira, a Jewish writing of the second century B.C., also known as Ecclesiasticus. Considered part of the Bible by Catholics, and part of the Apocrypha by Protestants and Jews, “The Wisdom of Ben Sira” had not been seen in its Hebrew version for about a thousand years. It had been dropped from the Old Testament canon by Jews as not truly Biblical, but it had been preserved in the Greek and other translations by the early Christian Church.

Schechter’s discovery established for the first time that Ecclesiasticus had indeed been written originally in Hebrew. (In 1964, fragments of an original Hebrew text of Ben Sira were found at Masada by Yigael Yadin. They showed that Schechter’s leaf, although inscribed in the Middle Ages, was the authentic Hebrew text and not a translation from Greek into Hebrew as some skeptics had suggested.)

Mrs. Lewis now reported Schechter’s discovery to the press. This prompted others to search for additional Ben Sira material. Soon two Oxford scholars announced that they had found more Ben Sira leaves among recent acquisitions of the Bodleian. Suddenly a flurry of fresh press reports told of other Bible-related pieces that had been recently acquired by English libraries. As Schechter personally examined many of these, he came to suspect what no one else had yet realized: Most of this new material was coming from a single source, and in all likelihood that source was the Genizah of the thousand-year old Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fostat, Old Cairo.

Fostat had once been a major center of Jewry, especially in the 11th and 12th centuries, when Egypt, along with much of the Near East, North Africa and parts of Europe, was under Islamic rule. Its thriving Jewish community had had close connections with sister communities in Babylonia, Palestine, Spain and other Mediterranean lands. Prominent Jewish scholars and religious leaders, like Saadia Gaon (882–942), Yehuda Halevi (1075–1141) and the renowned theologian and philosopher, Moses Maimonides (1135–1204) either lived in Fostat or stopped off there in their travels.

Schechter hardly dared to dream of what the Fostat synagogue Genizah might contain. He knew that he must go to Cairo to try to “empty” the Genizah and bring the mass of its contents back to Cambridge for scholars to study. Supported by colleagues, he took his plan to the Cambridge authorities and won their approval. His friend, Dr. Taylor, provided the funds for the expedition out of his personal means. In December 1896, Schechter sailed for Egypt armed with an impressive letter of recommendation from Cambridge University to Cairo’s Jewish leaders, and another to Cairo’s Grand Rabbi from the Chief Rabbi of Britain.

Contrary to popular belief, Schechter did not discover the Cairo Genizah and took pains to disclaim that he had. Its existence, as well as that of other genizahs in Europe and Asia, had been known, more or less, to several generations of travelers, manuscript hunters and scholars. Considerable misfortune, however, supposedly awaited those who attempted to remove the Cairo Genizah’s contents. One legend told of a great snake that protected the entrance to the Cairo Genizah and attacked would-be collectors. Such stories may have played a part in preserving the Genizah’s contents over the centuries.

041

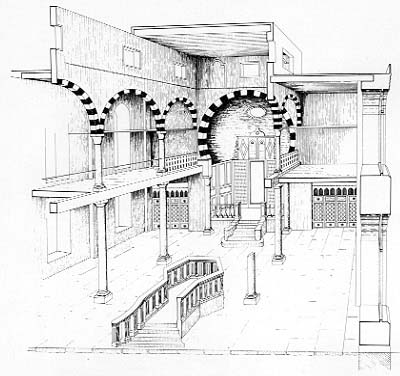

Still another deterrent may have discouraged would-be collectors: the real difficulties they would encounter in trying to enter and search the Genizah proper. It was a kind of attic chamber—dark, airless and windowless. The entry was a hole reached by climbing a high, shaky ladder which stood against the end-wall of the synagogue’s women’s gallery. Jacob Saphir, a 19th-century scholar and traveler, entered the Genizah in 1864, but he left after two days without retrieving anything of importance; he was defeated by the dust, the dirt and the hordes of insects.

From the middle of the 19th century, however, despite deterrents, Cairo Genizah material found its way into the hands of individuals and institutions in England, Palestine and elsewhere. Cambridge University acquired its first manuscript fragment from the Cairo 3 Genizah in 1891. Fragments were generally secured from Cairo’s dealers in “antikas,” and their real source went unrecognized. As for the dealers, they had discovered that baksheesh, liberally extended to the keepers of the Synagogue, overcame many obstacles.

At least two visitors to the Ben Ezra Synagogue who preceded Schechter managed to secure significant amounts of Genizah material on their own. Both are remembered as among the most industrious and successful collectors of Hebrew manuscripts of their times.

One was Abraham Firkowitch (1786–1874), who appears 043to have reached Cairo in the late 1860’s. Firkowitch was a Karaite rabbi from the Crimea who was especially interested in finding material that supported the Karaite rejection of talmudic Judaism. Two large collections amassed by Firkowitch are now part of the important Hebraica holdings of the Saltykov-Scherin Public State Library in Leningrad. The second collection is reported to hold valuable items that probably came from the Genizah.

The second earlier manuscript hunter was Elkan Nathan Adler (1861–1946), London lawyer, bibliophile and world traveler, who acquired a vast Hebrew library that included approximately 5,000 Hebrew manuscripts and fragments, now owned by the Jewish Theological Seminary of New York. In January 1896, Adler was permitted to take away from the Cairo Genizah as much material as he could carry in an old Torah mantle. Schechter talked briefly with Adler before leaving for Cairo.

It remained for Schechter, however, to penetrate the fabled storeroom and to empty it more or less. This feat required every bit of his considerable persuasive powers, his patience, his scholarship and, important as everything, his sheer physical stamina. It also required considerable baksheesh to mollify the synagogue’s custodians. After all, with every fragment he took, he was depriving them of their “fringe benefits”—the items they could sell surreptitiously to visitors and dealers.

The incomplete record suggests that Schechter spent six to eight weeks in securing his prize. He left for Egypt in mid-December 1896. By the latter part of January 1897, he wrote from Cairo that the work was done “thoroughly” and that he intended to send the results back to England. He added his frequent complaint: “People steal fragments and sell them to dealers.”4

Jews, since ancient times, have buried worn out or defective copies of sacred texts to keep them from desecration. Normally, a genizah attached to a synagogue, as in Cairo, served as a temporary storage place until its contents could be buried in consecrated ground. No one knows why the contents of the Cairo Genizah were permitted—fortunately—to accumulate for centuries. But Schechter’s proposal to the Grand Rabbi and the lay heads of the Cairo Jewish community to “empty” the Genizah and to take away its “almost” buried works must have struck them at first as an unthinkable profanation.

Here Schechter’s vast knowledge of Jewish law and tradition undoubtedly stood him in great stead—and provided the assurances that, on the contrary, the transfer to a great university would mean the respected preservation of the Genizah’s manuscripts and texts.

In due time the Grand Rabbi drove with Schechter to the Ben Ezra synagogue and showed him around. Schechter wrote: “The Rabbi introduced me to the beadles of the synagogue, who are at the same time the keepers of the Genizah, and authorized me to take from it what, and as 044much as, I liked.”5 Armed with this critical endorsement which the keepers could hardly ignore, he was at last able to climb into the storeroom. He described what he found:

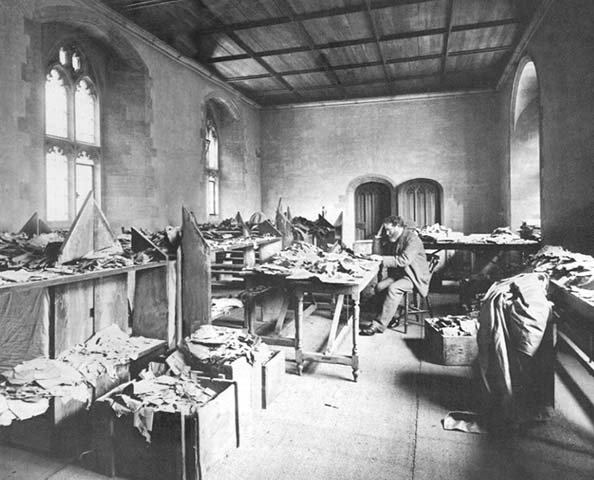

“It is a battlefield of books, and the literary productions of many centuries had their share in the battle, and their disjecta membra are strewn over the area. Some of the belligerents have perished outright, and are literally ground to dust in the terrible struggle for space, whilst others are squeezed into big, unshapely lumps, which … can no longer be separated without serious damage.”6

Inside the Genizah, Schechter also found a serious threat to his health. Every move stirred up the dust of centuries—dust which got into his eyes, throat, every pore. He felt threatened with suffocation, but he persisted. To get the job done, he reluctantly accepted the help of the synagogue’s keepers, who declined regular payment but asked for baksheesh. Later, he noted drily that baksheesh “besides being a more dignified kind of remuneration, also has the advantage of being expected for services not rendered.”7 Schechter also bought, from a dealer in “antikas” in Cairo, some items that especially interested him—items which quite apparently had just come from the Genizah.

Schechter more or less confined his search to securing manuscript material. He chose few printed works, dismissing them as “parvenus.” In a few weeks he had some 30 large bags crammed with his finds. When he ran into difficulties trying to export his material to Liverpool, he turned for help to the Office of the British Agent. The difficulties promptly vanished. Lord Cromer, the British Agent, was a Greek scholar who could readily appreciate the fact that Schechter’s fragments would add to England’s cultural treasures. He was also the virtual ruler of Egypt.

By early spring—after his only visit to Palestine—Schechter went back to Cambridge. He plunged at once into the enormous task of examining, classifying, 045conserving and storing his great haul. He estimated that he had secured 100,000 fragments and texts. But today at Cambridge, the collection is counted at 140,000 pieces.b It has taken eight decades to preserve, classify and house all the pieces so they can be readily studied by scholars.

News of Schechter’s scholarly exploit spread quickly. Soon he was something of a celebrity. Learned men came to visit him in his workroom in the university library and to get a glimpse of what he had brought back from Cairo. Dr. Taylor came by almost daily to help look for more Ben Sira leaves and to examine, with considerable enjoyment, any new finds.

In June 1898, the senate of Cambridge University was advised that Dr. Taylor and Dr. Schechter had offered the university on certain conditions, “the valuable collection of manuscripts … brought back from the Genizah of Old Cairo with the consent of the heads of the Jewish community.” The offer was duly accepted on November 10, 1898, thereby establishing the now famous Taylor-Schechter Genizah Collection of Cambridge University Library.

Schechter’s first hope had been to “empty” the Genizah. He did do a splendid job of taking away its oldest material, but he did not empty it, and others finished the task. Today, though there are other important collections of Genizah material (secured both before and after Schechter’s expedition) in Oxford, London, New York, Leningrad and other centers, none matches the collection at Cambridge either in size or in the volume of significant findings.

Until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Taylor-Schechter Genizah collection easily represented the most important recovery of ancient Hebrew manuscript material in modern times. For some, because it has furnished so many fresh insights into forgotten centuries of Jewish life and thought, it still is.

Schechter himself left Cambridge in 1902 to become the President of the Jewish Theological Seminary of New York, a post he held until his death in 1915. In the United States, he helped to build the then struggling Conservative movement into a major institution of contemporary Judaism. He came to New York hoping to initiate studies in a number of areas suggested by some of the Genizah 046fragments he had just examined. But the demands of his post soon made this impractical and he began to encourage others at the Seminary to undertake such studies.

He did, however, continue to work on two unusual writings he had found in the Cairo Genizah. In 1910 he published the results, a two-volume work entitled Documents of Jewish Sectaries. Volume II was called Fragments of the Book of Commandments by Anan. Anan is regarded as the eighth century founder of Karaism, a Jewish schism based on the literal interpretation of Scripture, rejecting the Talmud or Oral Tradition. Karaism still exists and has a small number of followers. (See accompanying article on “Essene Origins—Palestine or Babylonia,” BAR 08:05.) Volume I contained Schechter’s Fragments of a Zadokite Work and was devoted to the now-famous “Damascus Document,” which would one day be referred to as the first Dead Sea Scroll.

The Damascus Document (CD is its scholarly abbreviation) is a codex—a book. It consists of two partially overlapping and incomplete manuscripts. The first (A) dates to the 10th century, and the second and shorter manuscript (B) dates to the 12th century. The language of both is Biblical Hebrew and reflects none of the later developments in the Hebrew language which took place after Jerusalem fell to the Romans in 70 A.D. From this Schechter correctly concluded that the original text of his two medieval manuscripts must have been written before the Roman destruction of the Temple.

The Damascus Document reveals the history of a Jewish sect that saw itself as the True Israel and was in bitter opposition to the Jewish religious leaders in Jerusalem. The sect’s beginnings are traced to an “Age of Wrath” which occurred in about 196 B.C., 390 years after the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. During the “Age of Wrath,” the document indicates, pious people groped for the way to righteousness. A “Teacher of Righteousness” sent by God arose to guide them. But a powerful enemy arose also, in the person of “The Man of Scoffing.” Accordingly, the “Teacher” and his faithful followers fled from Judea to “the Land of Damascus.” There they adopted a “New Covenant,” and there too the Teacher was “gathered in.” He was expected to arise again as a Messiah “in the end of the days.”

The second section of the Damascus Document contains the laws of the sect. These reflect a highly structured organization. The sectaries were divided into priests (who were called “b’nei Zadok“—the sons of Zadok), Levites, Israelites and proselytes. The laws also reflect the sect’s own interpretation of certain Biblical injunctions, and include among other matters, strict observance of the Sabbath, 049strict monogamy without divorce, and rigid rules of cleanliness as a part of religious observance. The sect also followed a heterodox calendar of 12 months of 30 days each, plus 4 intercalary days.

From the fact that the priests were called the “sons of Zadok” and other evidence, Schechter advanced the hypothesis that the people of his manuscripts were the same mysterious “Sect of the Zadokites” referred to in the little-known early writings of the Karaites.

Zadok, to whom the Damascus Document makes direct reference, was King David’s chief priest and the founder of the line from which the High Priest of the Temple was always chosen until the second century B.C. Then, under the ruling Greeks, the High Priest’s office went to the highest bidder, and under the later Maccabees, the Hasmonaeans themselves occupied the office. But to “The Teacher of Righteousness” and his followers, such High Priests were illegitimate. The members of the sect apparently saw themselves as the inheritors of Zadokite tradition and practice and thus the true upholders of Jewish religious belief.

Schechter could only offer a hypothesis about the identity of the sect. But he made a number of observations about their way of life which are startling to read today because his descriptions border, so it seems, on prophecy.

Noting several references to their then-unknown works, he writes: “The Sect must also have been in possession of some Pseudepigrapha now lost.” A little later he writes: “This might suggest that the Sect was in possession of some sort of manual containing the tenets of the Sect, and perhaps a regular set of rules of discipline.”8

Fifty years later, with the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, many of the lost Pseudepigrapha began to make their reappearance. Included was one scroll with “a regular set of rules of discipline,” (now known as The Community Rule–1QS).

The publication of the Damascus Document anticipated the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in still another way. Shortly after the scrolls were found, exaggerated claims appeared about their relationship to early Christianity. Some even identified the Teacher of Righteousness in the scrolls as Jesus. Others saw the Qumran sect as a direct forerunner of Christianity, led possibly by John the Baptist. These same assertions had all been made before, shortly 050after Schechter published the Damascus Document. On Christmas Day, 1910, a front-page news story in The New York Times carried the following explosive headlines:

JEWISH MANUSCRIPT

ANTEDATING GOSPELS

Dr. Schechter Finds a Writing of

The First Century of the

Christian Era

REFERS TO “NEW COVENANT”

Describes Personages Believed to be

Christ, John the Baptist, and

the Apostle Paul

One had to read the story very carefully to discover that it was not Schechter who had linked the Damascus Document with the beginnings of Christianity. The headline catching theory had been advanced by Dr. George Margoliouth, Custodian of Hebrew Manuscripts of the British Museum. Reviewing Schechter’s publication, Margoliouth had announced his own conclusions regarding the Damascus Document.

According to Margoliouth, the text originated in a “primitive Judeo-Christian body that … strove to combine full observance of Mosaic Law with the principles of the ‘New Covenant.’” As Margoliouth read the Damascus Document, the sect had two Messiahs. The first, a priestly Messiah descended from Aaron, was John the Baptist. The other, “The Teacher of Learning” (or Teacher of Righteousness), was surely Jesus! As for the “Man of Scoffing,” he was none other than Paul, whom the sect abhorred as a Christian Hellenizer.

051

The Times continued to exploit this story of a “Hebrew Gospel earlier than the Gospels of the New Testament” by devoting a full page feature to it a week later in its Sunday magazine. Schechter himself largely ignored this sensational interpretation which he had done nothing to encourage. Margoliouth, however, continued to bark his theory at Schechter’s heels for several years.

In late 1947 and early 1948, the world had not yet heard of the extraordinary discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. But in the tense city of Jerusalem, scholars were examining the first of the newly uncovered scrolls—seven in all. They had been found in a cave near Qumran by Bedouin tribesmen and brought to a dealer in Bethlehem. (See “How the Dead Sea Scrolls Were Found,” BAR 01:04, for the story of the discovery.)

The distinguished scholar-archaeologist E. L. Sukenik (father of Yigael Yadin) immediately saw the connection between the Damascus Document and the Dead Sea Scrolls when he examined the three scrolls he had purchased in late 1947 for the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

In March 1948, Millar Burrows, Director of the American Schools of Oriental Research, independently recognized the relationship. With two young scholars, John C. Trever and William H. Brownlee—both now famous for their Dead Sea Scroll research—Burrows examined the four remaining scrolls which were then owned by the Metropolitan Samuel, head of the Syrian Orthodox monastery of St. Mark. The Metropolitan had bought them from the same dealer who had sold the first three scrolls to Dr. Sukenik.

The scrolls included both the Habakkuk Commentary (1QpHab) and the Manual of Discipline (or The 052Community Rule–1QS), the two works most clearly related to Schechter’s Damascus Document. Burrows, looking at the Habakkuk Commentary, was struck by the similarity of its details to the strange document that he recalled had been recovered years before in the Cairo Genizah. The three scholars immediately secured Schechter’s publication “Fragments of a Zadokite Work” from the school’s library.

“The similarity of the contents was unmistakable,” Burrows wrote later. “I remember Brownlee’s enthusiasm when he found the Teacher of Righteousness and other characters of the Habakkuk Commentary in the Damascus Document.“9 Now it was clear. The sect of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the sect of the Damascus Document were the same.

The relationship between the Qumran sect and the sect described in the Damascus Document was soon to be pinned down beyond any doubt. In September 1952, Bedouin tribesmen discovered what are now known as Qumran Caves IV and VI. Archaeologists found little in the way of fragments in Cave VI, but that little included small bits of a copy of the Damascus Document! These bits have been dated to about 754–30 B.C.

Qumran Cave IV contained nearly 15,000 scroll fragments representing some 400 manuscripts. From these, scholars eventually identified fragments of no fewer than seven copies of the Damascus Document!

J. T. Milik, one of the editors of the Dead Sea Scrolls, has studied all of the Damascus Document fragments found at Qumran. He has concluded, as Schechter had earlier, that the Genizah text is incomplete and lacks both its beginning and ending. These lacunae have now been partly restored 053by the Qumran fragments. The same fragments have supplied additional regulations by which the Scroll Sect was governed. Milik has al so shown that the paging in Manuscript A of the Genizah text is out of order and he has corrected it.

With the fragments from Qumran, scholars have reestablished what the complete Damascus Document said. But the new fragments only supplement, they do not supplant, the manuscripts which Solomon Schechter found in the Genizah. From the Genizah documents, Schechter gave us our first picture of the people of the scrolls—somewhat blurred, but recognizable—well before the scrolls were discovered at Qumran. And from all the rediscovered writings, today’s scholars have extracted new insights into who the scroll people really were.

BAR wishes to thank the Syndics of Cambridge University Library and Dr Stefan C. Reif, Director of the Taylor-Schechter Genizah Research Unit, for permission to publish the photographs that accompany this article.

Some call it the first Dead Sea Scroll—but it was found in Cairo and not in a cave. It was recovered in 1897 in a Genizah, a synagogue repository for worn-out copies of sacred writings. The gifted scholar who had found it, Solomon Schechter, gave it with a hoard of other ancient Hebrew manuscripts to Cambridge University, where it still remains today. Of course no one called it the first Dead Sea Scroll in 1897. That was fifty years before the momentous discovery on the actual Dead Sea Scrolls, in 1947, in the caves of Qumran on the northwest […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Schechter titled his study “Fragments of a Zadokite Work” because the sect that wrote the document followed the Zadokite tradition, calling their priests the sons of Zadok, descendents of King David’s high priest.

Endnotes

S. Schechter, Documents of Jewish Sectaries: Fragments of a Zadokite Work (C.U.P., Cambridge, 1910), Introduction, p. xviii.

Norman Bentwich, Solomon Schechter, A Biography (The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1938), p. 130.

S. Schechter, Studies in Judaism: Second Series (The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1908), p. 6.

S. Schechter, Documents of Jewish Sectaries: Fragments of a Zadokite Work, Introduction, pp. xv, xvi.