The Second Jewish Revolt against Rome, also known as the Bar Kokhba Revolt after its almost legendary leader, lasted from 132 to 135 C.E. Like the First Jewish Revolt of 66–70 C.E., it was brutally crushed. But, unlike the First Revolt (in which the Temple was destroyed), there was no Josephus to record its history. For an account of the Second Jewish Revolt, we are dependent almost entirely on archaeology.

We are still not sure of its direct cause, the geographical extent of Bar Kokhba’s command, whether his territory included Jerusalem, or the magnitude of the Roman reaction.

What we do know of the Second Jewish Revolt was sparked in a curious way by the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947. The scrolls discovered at that time and in the years thereafter produced texts from the fourth century B.C.E. to 68 C.E., when the Romans destroyed Qumran on their way to Jerusalem. The treasures of these caves, however, naturally led to the exploration, both by Bedouin and by scholars, of other caves north and south of Qumran, especially caves in wadis that lead into the Dead Sea.

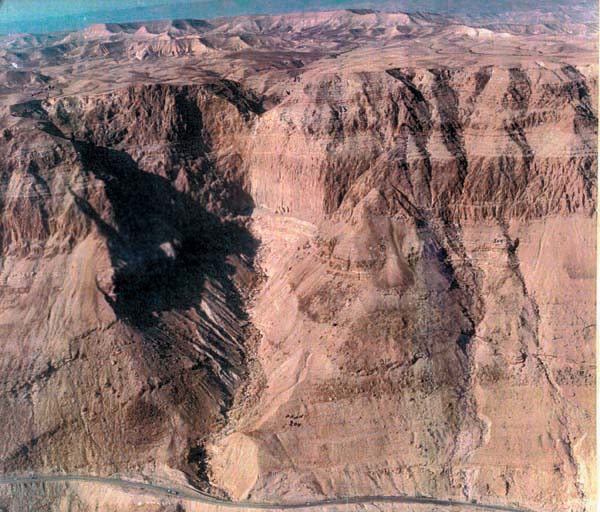

In the early 1950s, in a cave in the Wadi Murabba’at, the first letters were found with direct reference to Bar Kokhba himself. In 1960, Israeli academic institutions joined with the Israel Defense Forces to systematically explore caves in four wadi systems. The highlight of this project was the discovery in the so-called Cave of Letters in Nahal Hever of 15 letters sent by Bar Kokhba to his officers at Ein Gedi. In 1961, an archive of personal documents hidden by a woman named Babatha was found in the same cave.

From these and other caves and other finds, it became clear that these were refuge caves where Judeans had fled to escape from the Romans during the revolt. Barely hinted at in written sources, the refuge caves moved to center stage of Second Revolt research.

Between 1947 and 1965, more than a thousand ancient documents were discovered in the Judean Desert from before both the First Revolt and the Second Revolt, culminating in the excavation of Masada, where the rebels held out for another three or four years after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 C.E.

As a result of the Six-Day War in 1967, other sites in Samaria and Judea that featured in the Second Revolt became available to Israeli archaeologists. At a number of sites, hiding complexes and tunnels were discovered. At the end of the 1970s, hiding complexes that were part of the preparation for the revolt were discovered adjacent to or underneath domestic buildings in the Judean Shephelah.

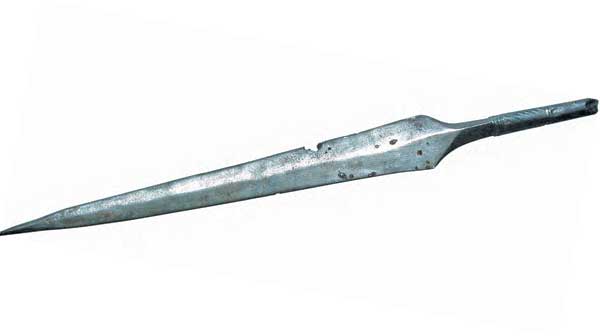

In the 1980s, the Israel Cave Research Center joined the search. Now part of the Hebrew University, the Israel Cave Research Center is a nonprofit archaeological research center that has made great contributions to the field of refuge-cave research. In 2001, the Archaeological Institute of Bar-Ilan University teamed up with the Cave Research Center to continue the search. Together, they have located more than 350 caves containing weapons, food remains (olive and date pits, barley kernels, pomegranate peels, etc.), ropes, baskets, fragments of sandals, pottery, glass, arrowheads, a large spearhead and other artifacts. Four caves contained coins from the Bar Kokhba period. In one cave two papyrus documents dating from this period were found.

Especially rich were the caves around Ein Gedi. A refuge cave about 7 miles north of Ein Gedi, called the Cave of the Spear after a rare weapon of the revolt that was found there, was more than 100 feet long and contained three substantial halls. The iron spear was found at the entrance to this cave.

In another cave (the Zabar Cave) the survey discovered a Bar Kokhba tetradrachm depicting the façade of the Jerusalem Temple. This is only the second Bar Kokhba tetradrachm ever retrieved in a scientifically controlled excavation. Along with it were six Roman dinars and two additional Roman dinars that had been overstruck as Bar Kokhba dinars. The value of this coin hoard was more than the value of a house then, in the third year of the revolt.

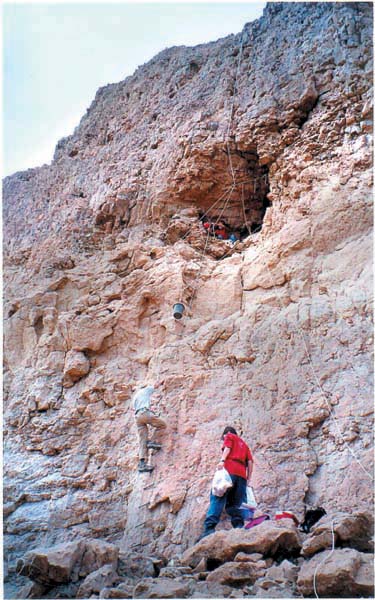

In 2004, while surveying caves in the Wadi Arugot adjacent to Ein Gedi, the survey team was told that that summer, Bedouin from the Rashaidah tribe had found four small fragments of a parchment scroll in a small, nearly inaccessible cave in the wadi. Members of the survey team were taken by the Bedouin to the supposed find spot—the easternmost of a group of four small caves on the southern bank of the wadi, under the large waterfall. These caves also yielded pottery and textiles of the period of the Bar-Kokhba Revolt.

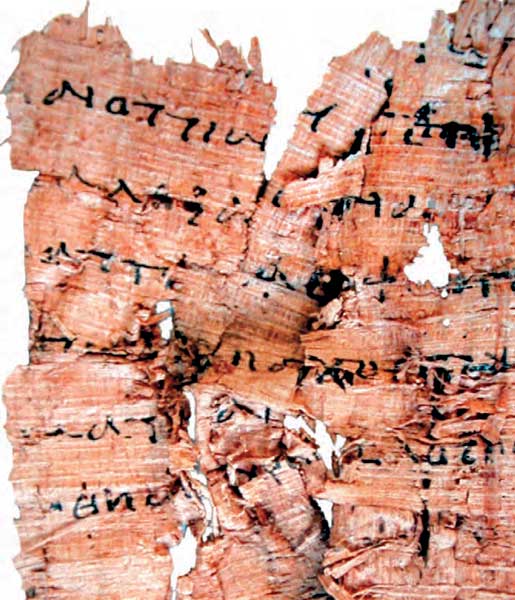

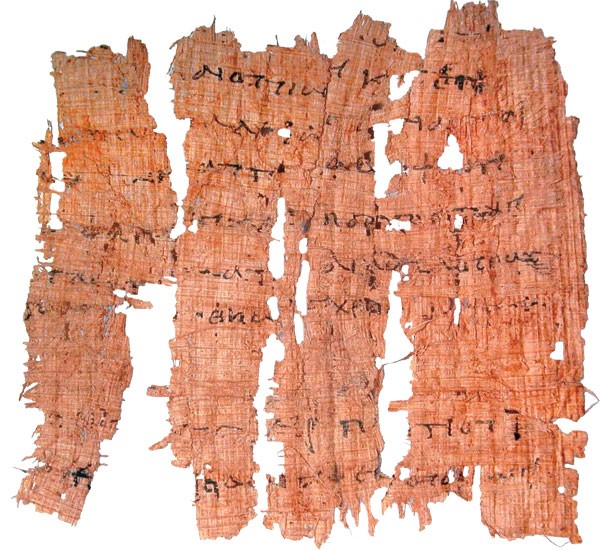

The scroll fragments include parts of verses of Leviticus 23 and 24. The scroll was written in two columns, with 36 lines to a column. This suggests that the scroll included only the Book of Leviticus, because in scrolls that contain the entire Pentateuch there are between 44 and 45 lines per column; while scrolls that had only one book have between 30 and 41 lines to a column.

In August 2004, while the fragments were still in possession of the Bedouin and before they were cleaned, the fragments were photographed. A preliminary report was published in Meghillot Volume 3 (2005) on the basis of these photographs.

In February 2005, we were told that two of the fragments were covered with glue and deteriorating. Fearful that they would find their way to the international antiquities market and be lost to scholarship, we purchased the fragments from the Bedouin with $3,000 supplied by our university. The fragments were subsequently turned over to the State of Israel.

These fragments are similar to the 14 other Bar Kokhba scrolls found in the Judean desert between 1951 and 1962. Until now, fragments of the four other books of the Pentateuch had been found from the Bar Kokhba period, but not Leviticus. This is the first time that a copy of Leviticus from this period has been found.

Together, these pentateuchal fragments indicate that the process of creating a single authorized text had already begun at this time. This is in contrast to the Biblical texts found at Qumran from the period before the destruction of the Temple. The Biblical texts there vary widely, representing different textual traditions—for example, the tradition of the Greek translation known as the Septuagint, as well as the standard Jewish textus receptus known as the Masoretic Text. The scrolls from the Bar Kokhba caves, however, reflect conformity to the Masoretic Text. By that time, a single standardized text was beginning to emerge.

Moreover, the discovery of these fragments demonstrates that there is still a chance to find additional scrolls in the Judean Desert caves despite the widespread plundering that has occurred since the first scrolls were unearthed at Qumran in 1947. The search should continue.

Photos courtesy of the authors.