For some, opportunities for adventure come once in a lifetime; for BAR readers, they come every year in the annual list of digs. Thousands of volunteers, of all ages and backgrounds, from all around the world, boldly set off for excavation sites known to them, perhaps, only as names from the Bible. These volunteers learn the rudiments of archaeology while they sift for the remains of ways of life long past.

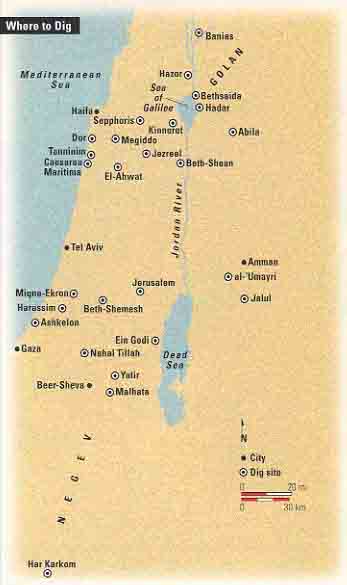

This issue provides essential information about digs needing volunteers. Descriptions of each site’s historical significance and Biblical connection begin below.

As the grins of the volunteers pictured in this section show, the work—while neither glamorous nor easy—provides an immense satisfaction that you won’t find at summer camp or at the beach. Make history come alive this summer—join a dig.

Abila

One of the cities of the Decapolis—a federation of ten cities in eastern Palestine (Matthew 4:25; Mark 5:20, 7:31)—Abila appears in the works of several ancient writers such as Polybius, Pliny the Elder and the geographer Ptolemy. It is located about 9 miles from Irbid, in northern Jordan.

Nine seasons of survey and excavation have revealed evidence of human habitation during every period from the Neolithic (8300–4500 B.C.) onward. The site’s highlights include an inscription with the name of the city; five churches—two of them large Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) basilicas; a life-size marble statue of Artemis (or Diana), the Greek (Roman) goddess of the hunt; a cache of early glass lamp fragments; an extensive Roman-Byzantine cemetery; several painted tombs; and an extensive underground aqueduct system.

In the coming season, dig director W. Harold Mare (Covenant Theological Seminary) will search for more of the Bronze Age (3150–1200 B.C.) and Iron Age (1200–586 B.C.) cemetery; further excavate the aqueducts, public bath and church ruins; and probe for more of the Bronze Age settlement.

The site is open to visitors all year. Guided tours are available during the excavation season.

El-Ahwat

Located on a high hill 9 miles east of Caesarea, el-Ahwat is the site of the northwestern-most Israelite settlement in the region of Manasseh. The first three seasons of excavation revealed a large, heavily fortified village of the Iron I Age (1200–1000 B.C.), with a city wall, towers and gate. Excavations also uncovered cylinder seals, Egyptian scarabs, several bronzes and pottery. During the coming season, dig director Adam Zertal (Univ. of Haifa) expects to unearth the fortifications and determine the site’s Biblical background.

The site is open to visitors by appointment during excavations. Guided tours are available.

Ashkelon

Ashkelon was a major seaport of the Canaanites and Philistines from 3000 to 604 B.C. The Bible frequently mentions the Philistine city at the site. Samson went there in a rage and killed 30 men (Judges 14:19); David lamented, “Proclaim it not in the bazaars of Ashkelon,” when he learned of the deaths of Saul and Jonathan, slain by the Philistines at the Battle of Gilboa (2 Samuel 1:20); and the prophet Jeremiah, in his oracle against the Philistines, declared that “Ashkelon has perished” and that “the sword of the Lord,” in the hands of King Nebuchadnezzar and his army, was drawn “against Ashkelon and against the seashore” (Jeremiah 47:5–7).

Previous work at this large seaside site, located in a National Park, uncovered the world’s oldest arched gateway, featured on the

In 1996, director Lawrence E. Stager (Harvard Univ.) will continue to expose the massive city gateway and the architecture of the major residential zone and will interpret and expose the stratigraphy of the port-side.

The site is open to visitors by appointment. Guided tours must be arranged in advance.

(See Lawrence Stager, “The Fury of Babylon—Ashkelon and the Archaeology of Destruction,” in this issue, and the following 1991 BAR articles by Stager: “When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR 17:02; “Why Were Hundreds of Dogs Buried at Ashkelon?” BAR 17:03; “Eroticism and Infanticide at Ashkelon,” BAR 17:04.)

Banias

Lying at the foot of Mount Hermon, Banias overlooks the Jordan Valley’s fertile northern end, an area of lush vegetation and abundant opportunities to walk and swim. A large, nearby spring gushes from the mouth of the famous Cave of Pan, a rural sanctuary established when the region fell under the rule of the Ptolemies in the third century B.C. and mentioned by many ancient writers. As the Greek historian Polybius tells, Antiochus the Great defeated Egypt in an important battle at Banias in about 200 B.C. Jesus visited the area (Matthew 16:13; Mark 8:27), and many important Roman buildings were erected here. Flavius Josephus, the first-century A.D. Jewish historian, records that Herod the Great built a temple to Augustus at Banias and that Herod’s son Philip enlarged and beautified the city, which he renamed Caesarea Philippi.

Two separate excavations are working at Banias, one at the site of the ancient city and the other at the Hellenistic-Roman cult site in the grotto of Pan. The excavation of the city, under the direction of Vassilios Tzaferis (Israel Antiquities Authority), has brought to light the remains of a monumental first-century A.D. Roman city (including an early Roman basilica) and building remains from the Byzantine (324–640 A.D.), Crusader (1099–1291 A.D.) and Mamluk (1250–1516 A.D.) periods. In the coming season, Tzaferis plans to continue excavation of a large early Roman building, tentatively identified as a health and recreation center.

The excavation of the religious sanctuary in the grotto of Pan, directed by Zvi U. Ma‘oz (Israel Antiquities Authority) and Andrea M. Berlin (Univ. of Illinois), has uncovered Herod’s temple to Augustus, as well as other temples and shrines; life-size marble heads of Athena, Zeus and Aphrodite; marbles depicting hands holding Pan pipes; and Greek and Latin inscriptions. Next season, Ma‘oz and Berlin will unearth the temple to Augustus and probe Hellenistic structures beneath the Roman temples on the site’s terrace.

The excavation is open to visitors all year by appointment, and guided tours are available.

Bethsaida

The Gospels mention Bethsaida more often than any other town except Jerusalem and Capernaum. In this birthplace of the apostles Peter, Andrew and Philip, Jesus restored a blind man’s sight (Mark 8:22–26) and fed the multitude (Luke 9:10–17). In addition, Josephus led forces that clashed with the Romans here during the First Jewish Revolt (66–70 A.D.).

Located on the east side of the Jordan River, just north of the Sea of Galilee, Bethsaida has yielded a residential quarter dating to Jesus’ time; a delicate statuette of the Egyptian god Pataekos, featured on the

The site is open to visitors, primarily during the excavation season, by appointment. Guided tours are available.

(See Rami Arav, “An Iron Age Amulet from the Galilee,” BAR 21:01.)

Tel Beth-Shean

After Saul and his sons were slain on Mount Gilboa, the Philistines displayed Saul’s body on the city wall of Beth-Shean (1 Samuel 31:8–10). The site of Beth-Shean marks one of the longest, essentially unbroken occupations in Palestine, stretching from the fifth millennium B.C. to the Byzantine period (324–640 A.D.). The city served as an Egyptian stronghold during Egypt’s domination of the region in the Late Bronze Age, and it resisted the Israelite attack during the Canaanite occupation. King David, however, eventually conquered the city when he expanded his kingdom northward (1 Kings 4:12).

The tell, overlooking the dramatic Roman remains in the later city, is especially noted for its Canaanite temples and for the abundance of cult objects unearthed by previous digs. The expedition, led by Amihai Mazar (Hebrew University), has uncovered a 15th-century B.C. Canaanite temple and an Egyptian residence from the 12th century B.C. In the coming season, work will continue on the Bronze Age and Iron Age occupation levels.

The site is open to visitors all year.

Tel Beth-Shemesh

Once a major Canaanite city-state and later an Israelite royal administrative center, Beth-Shemesh has strong Biblical associations. Located in the Shephelah about 16 miles from Jerusalem, it stood on the western border of the kingdom of Judah, facing powerful Philistine neighbors. The area was the scene of Samson’s struggles, and when the Philistines gave back the Ark of the Covenant, which had plagued them for months after its capture at the battle of Ebenezer, they returned it to Beth-Shemesh (1 Samuel 6). Beth-Shemesh became an important part of King Solomon’s administrative organization (1 Kings 4:9) and one of the few centers assigned to priestly families (Joshua 21:16). The site retained its importance throughout the period of the Judahite Monarchy and was the site of the battle in which King Jehoash of Israel defeated and captured the overly ambitious King Amaziah of Judah (2 Kings 14:11). During the time of King Ahaz of Judah (731–715 B.C.), “The Philistines had taken Beth-Shemesh … and settled there” (2 Chronicles 28:18). The Assyrian emperor Sennacherib (701 B.C.) destroyed Beth-Shemesh during his violent military campaign, and, thereafter, the site’s importance dwindled.

Excavations have revealed massive fortification systems and domestic and public structures from the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.) and Iron Age (1200–586 B.C.). Other discoveries include one of the earliest known olive-oil production centers, a unique rock-cut reservoir and many metal artifacts, pieces of jewelry, and seals and tablets. In 1996, directors Zvi Lederman (Ben-Gurion Univ.) and Shlomo Bunimovitz (Bar-Ilan Univ.) will uncover the final destruction of the Canaanite city, expose parts of the fortification system and city gate from the early Biblical period, reveal a large water system from the time of King Hezekiah (ruled 727–698 B.C.) and excavate the newly discovered Iron Age village.

Caesarea Maritima

A marvel of ancient engineering, Caesarea’s harbor could hold an entire Roman fleet. Herod the Great built the city and harbor between 22 and 10 B.C. on the site of an earlier Phoenician and Hellenistic trading station known as Strato’s Tower. A major port for over 1,000 years, Caesarea reached its zenith during the Byzantine period (324–640 A.D.), when it was the largest city in Palestine. Pontius Pilate resided in the city, and an inscription bearing his name has been found here. Peter’s conversion of the Roman centurion Cornelius (Acts 10:1–48) and Paul’s brief imprisonment (Acts 23–25) also occurred in Caesarea.

One of the largest and richest sites in Israel, Caesarea has an early Christian church, well-preserved ancient aqueducts, a warehouse district, a Roman-Byzantine bath complex, a public latrine, administrative buildings, a hippodrome, King Herod’s royal palace, a Roman theater in use once again for summer music and dance performances, and imposing fortifications from Crusader times. Underwater excavations have uncovered remains of ancient harbor breakwaters and shipwrecks. Excavations last summer revealed King Herod’s temple to Roma and Augustus. A cache of 200 intact glass, ceramic and copper vessels discovered on the temple platform dates to the Islamic period (640–1516 A.D.).

In 1996, directors Kenneth G. Holum (Univ. of Maryland), Avner Raban (Univ. of Haifa) and Joseph Patrich (Univ. of Haifa) will continue to uncover Herod’s temple. They also plan to open a new excavation area in the Old City, where they hope to uncover a dwelling quarter from the time of saints Peter and Paul. Underwater excavations of the harbor breakwater will also continue.

A national park, the site is open daily to visitors during regular park hours. Guided tours may be arranged through travel agents and hotels.

(See the following BAR articles: “Caesarea Maritima Yields More Treasures,” BAR 20:01; Barbara Burrell, Kathryn Gleason and Ehud Netzer, “Uncovering Herod’s Seaside Palace,” BAR 19:03; Kenneth G. Holum, “From the Director’s Chair: Starting a New Dig,” BAR 17:01; Lindley Vann, “Herod’s Harbor Construction Recovered Underwater,” BAR 09:03; Robert L. Hohlfelder, “Caesarea Beneath the Sea,” BAR 08:03; Robert J. Bull, “Caesarea Maritima—The Search for Herod’s City,” BAR 08:03.)

Tel Dor

A major Mediterranean port from the Bronze Age through the Roman period, Dor was one of the Canaanite cities defeated by Joshua (Joshua 12:23). Today Tel Dor is the site of one of Israel’s largest excavations.

Founded by the Canaanites as early as 1900 B.C., Dor fell to the Sikils—a Sea People tribe—in 1200 B.C. The Phoenicians reconquered the city in 1050 B.C. and dominated its culture for the next 800 years. Politically, however, Dor came under Israelite control and became the capital of one of Solomon’s administrative districts. After its conquest by Tiglath-Pileser III in 732 B.C., it served as an Assyrian administrative center. Dor became a major fortress in the Hellenistic Age. In 137 B.C., the Syrian king Trypho took refuge there and withstood a siege by Antiochus VII before managing to escape (1 Maccabees 15:10–14, 25, 37–39). The excavations have uncovered slingstones from that siege. Dor continued to thrive in the Roman period. A Crusader fortress in the 13th century was the last occupation of the site.

Past excavations at this beautiful site have revealed the main street, forum, sanctuaries, bathhouse, purple-dye works, a stoa, basilicas and aqueduct of the Roman city, as well as gates and fortifications from the Hellenistic, Persian and Iron Age cities. Archaeologists have also found two Iron I destruction levels with Philistine pottery, early Phoenician artifacts, a skeleton crushed beneath a fallen wall and a cow’s collarbone with a sailing scene and a dedicatory inscription.

In 1996, directors Andrew Stewart (Univ. of California, Berkeley) and Howard Goldfried (California State Univ., Sacramento) will continue to excavate the Roman and Hellenistic cities, including the public buildings and a Roman villa; expand work on the Persian and Phoenician occupations; and further explore the Israelite city.

The site is open Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to noon. Guided tours are available by appointment, but arrangements for groups must be made with Dr. Goldfried before the season begins.

(See the following BAR articles by Ephraim Stern: “Priestly Blessing of a Voyage,” BAR 21:01; “The Many Masters of Dor,” in three parts, in “The Many Masters of Dor,” BAR 19:01, “The Many Masters of Dor, Part 2: How Bad Was Ahab?” BAR 19:02, “The Many Masters of Dor, Part 3: The Persistence of Phoenician Culture,” BAR 19:03.)

Ein Gedi

Watered by a perennial spring, this lush oasis on the western shore of the Dead Sea lies about 20 miles south of Qumran, in the Judean desert. Pliny describes the site as “second only to Jerusalem in the fertility of its land and in its groves of palm-trees” (Natural History 5.73). In Ecclesiasticus (24:12, 14), Lady Wisdom praises herself: “I took root among the people whom the Lord had honored [and] … I grew like a date-palm at Ein Gedi.” In the Second Temple period (ending with the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 A.D.), the semitropical vegetation—in particular the local balsam tree, with its aromatic oil—brought prosperity to the Ein Gedi residents. In the Roman and Byzantine periods, Ein Gedi was home to a flourishing Jewish community. The fourth-century A.D. church father Eusebius described Ein Gedi as “a large village of Jews.”

Excavations in the 1970s uncovered the remains of a magnificent Byzantine synagogue. This building’s mosaic floor incorporates numerous inscriptions, including one that appears to hint that the village’s wealth resulted from the cultivation of plants used in medicine and perfume.

In 1997, director Yizhar Hirschfeld will systematically expose the settlement around the synagogue to determine the components of the village in the Talmudic period. Although he expects to discover glass, ceramics and papyri, more precise goals will not be known until the first season of excavation is completed in January 1996.

Tel Hadar

The Bible refers to the area east of the Sea of Galilee as Geshur, an Aramean kingdom (2 Samuel 15:8) that fell under the military control of King David (2 Samuel 8:3–8). Absalom, David’s son by a Geshurite princess, fled to Geshur and spent three years there after having his brother Amnon killed for the rape of their sister (2 Samuel 13:1–39).

A part of the Land of Geshur Regional Project, which is conducting the first excavations of the Biblical period in the Golan, Tel Hadar was a Geshurite stronghold in the late 12th to late 11th centuries B.C. The site features an 11th-century B.C. palace that may have belonged to Talmai, King David’s father-in-law (2 Samuel 3:3). The Canaanites also occupied the site as early as the 16th century B.C. Other finds at Tel Hadar include an intact granary with one room still filled with wheat, a building with a pillared hall, massive basalt fortifications, a Late Bronze (1550–1200 B.C.) circular tower with five rooms containing pottery, and Aramean inscriptions and figurines.

In the coming season, directors Moshe Kochavi (Tel Aviv Univ.) and Ira Spar (Ramapo College) will expand work on the Late Bronze excavation, complete work on the tower and begin excavating the early Iron I (1200–1000 B.C.) gate.

The site is open to visitors by appointment. Guided tours are available.

(See Moshe Kochavi, Timothy Renner, Ira Spar and Esther Yadin, “Rediscovered! The Land of Geshur,” BAR 18:04.)

Tel Harassim

The Shephelah, the hilly region bounded on the east by the Judean Plateau and on the west by the Coastal Plain, which extends to the Mediterranean Sea, was the stage for many events in the life of David. As a youth he defeated Goliath here (1 Samuel 17), and, after he became king, David used his knowledge of the local climate and terrain to defeat the Philistines (2 Samuel 5:22–25). In the center of the Shephelah lies Harassim (Kefar Menachem), a Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.) city destroyed and later rebuilt by the Israelites.

Past excavations have revealed a three-roomed house from the Late Bronze city and a public building (either a temple or palace) and a large fortress from the Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.).

In 1996, dig director Shmuel Givon (Bar-Ilan Univ.) will finish excavating the public building and will cut through the Iron Age strata.

The site is open to visitors in the summer.

Har Karkom

Boasting 40,000 petroglyphs—the largest concentration of rock art in the Negev—and 892 archaeological sites, the 75-square-mile survey in the vicinity of Har Karkom provides a rich field for exploration. Subject of a heated debate in BAR, Har Karkom is identified by archaeologist and dig director Emmanuel Anati (Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici) as a holy site from the time of the Exodus, perhaps even Mt. Sinai; but in the view of archaeologist Israel Finkelstein, it was simply a popular gathering place for nomads over the millennia. Whoever is right, the site has abundant pottery, altars, standing stones, campsites and tumulus gravesites dating from about 3000 to 2000 B.C.

In 1992, the expedition found a site believed to be a sanctuary from the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic Age, about 30,000 years ago. This site included approximately 40 large flint boulders with quasi-anthropomorphic shapes, numerous flint implements from the Near Eastern Aurignacian culture, 220 human- and animal-shaped pebbles bearing evidence of human modification, and drawings formed by arrangements of pebbles on the ground. The discovery of this Paleolithic site suggests that Har Karkom acquired its sacred quality far earlier than previously believed, perhaps as early as the first appearance of Homo sapiens.

In 1996, Anati will continue to survey the site, record the rock art and explore the caves. The site is open to visitors by appointment during the excavation season. Guided tours are available.

(See the following BAR articles: “30,000-Year-Old Sanctuary Found at Har Karkom,” BAR 19:01; Emmanuel Anati, “Has Mt. Sinai Been Found?” BAR 11:04; and Israel Finkelstein, “Raider of the Lost Mountain,” BAR 14:04.)

Hazor

Located in northern Galilee, Hazor was the site of an important dig and the subject of a popular book by the late Yigael Yadin, one of Israel’s most famous archaeologists. For its “enormous size and peculiar features,” Yadin said, “Hazor is unparalleled by any other site in the country.”

Hazor played an important role in Joshua’s conquests. Its king, Jabin, gathered together a league of kings to oppose Joshua. Consequently, when Joshua defeated them, he singled out Hazor and burned it (Joshua 11:1–13). Jabin also appears in the prose story of the battle between Deborah and Sisera (Judges 4). Solomon apparently rebuilt the city (1 Kings 9:15), which finally disappears from the Biblical record after its conquest by the Assyrian ruler Tiglath-Pileser III in 732 B.C. (2 Kings 15:29). Excavators at Hazor recently discovered a fragment of a royal letter addressed “To Ibni,” a name similar in derivation to Jabin. Extra-Biblical references to Hazor include the Egyptian Execration Texts (c. 19th–18th centuries B.C.), which curse Hazor as an enemy of Egypt; and tablets from the royal archive at the Mesopotamian city of Mari, one of which notes that Hammurabi, the king of Babylon (1792–1750 B.C.), had ambassadors residing in Hazor.

The site contains temples and fortifications from the Canaanite period and administrative buildings, a citadel and an underground water system from the Israelite period. A basalt statue discovered last season in the courtyard of a Canaanite royal palace is the largest Bronze Age (3150–1200 B.C.) deity statue ever discovered in Israel. In 1996 director Amnon Ben-Tor (Hebrew Univ.) will examine the remnants of the early Israelite site, dating back to the tenth century B.C.; the Canaanite palace; and the architectural context of a Canaanite bamah.

The site, located in a national park, is open to visitors daily, from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

(See the following BAR articles: “Babylonian Tablet Confirms Biblical Name,” BAR 20:05; Hershel Shanks, “Ben-Tor, Long Married, Will Return to Hazor,” BAR 16:01;

Israel Archaeological Society

If you are torn between joining a real archaeological excavation and just touring the Near East, this private organization has a solution for you. The Israel Archaeological Society offers volunteers the opportunity to join a dig in Jerusalem’s Old City and to visit sites throughout Israel, Syria, Jordan and Egypt. Directed by the Israel Antiquities Authority, the Jerusalem dig is located beside the western wall, built by Herod the Great as part of his massive expansion of the Temple Mount platform.

Tall Jalul

Occupied as far back as the Early Bronze Age (3150–2200 B.C.), this Jordanian site lies 20 miles south of Amman. The city’s ancient name and historical background remain unknown.

Two seasons of excavation have uncovered abundant ash deposits indicating a massive destruction during Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.); two superimposed pavements from Iron II (1000–586 B.C.), which lead to a gate; a late Iron II pillared building; and scores of later burials.

In 1996, director Randall W. Younker (Andrews Univ.) will continue to expose areas from all periods represented at the site.

The deadline for submission of security forms is March 15.

The site is open to visitors on weekdays during the season, but an appointment is preferred. Guided tours are available.

(See Larry G. Herr, “What Ever Happened to the Ammonites?” BAR 19:06 and “The Search for Biblical Heshbon,” BAR 19:06.)

Tel Jezreel

Either King Omri (reigned 882–871 B.C.) or King Ahab (reigned 871–852 B.C.) and his wife Jezebel built Jezreel as a second capital of the northern kingdom of Israel. Standing on a spur of Mount Gilboa, at the edge of the Jezreel Valley, it served primarily as a winter residence for the royal family. Here Naboth was framed by Jezebel and executed so that Ahab could take possession of Naboth’s vineyard; as a result, Elijah cursed Ahab and Jezebel (1 Kings 21). Later, during his coup d’état in 842 B.C., Jehu took over Jezreel and there killed Jezebel and King Jehoram, Ahab’s son.

Excavators have revealed the eastern tower of the enclosure, reached the bottom of the moat, located the city gate and exposed a Crusader church. In 1996, dig director John Woodhead (British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem) will determine whether the site had a four- or six-chambered gate.

The site is open to visitors all year. Tours are possible with prior arrangement.

Kinneret

Located on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Kinneret has a long history beginning in the Early Bronze Age (3300–2200 B.C.). Joshua 19:35 mentions it as a fortified city of the tribe of Naphtali.

Excavations at this site have uncovered a city from the time of King David (10th century B.C.) and a lion bowl in the Assyrian style of the eighth century B.C. Dig director Volkmar Fritz (German Protestant Institute of Archaeology, Jerusalem) plans to spend the coming season exposing Early Bronze, Middle Bronze (2000–1550 B.C.) and Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.) remains.

The site is open to visitors, and guided tours are available.

Tel Malhata

The Biblical name of this important site in the Negev remains a mystery despite the discovery of Iron Age (1200–586 B.C.) city walls, buildings and related artifacts. Past suggestions have included Moladah, Hormah and even Arad. The site was occupied from the Middle Bronze Age (2200–1550 B.C.) through the Roman period (37 B.C.–324 A.D.).

In the coming season, directors Bruce Cresson (Baylor Univ.) and Itzhaq Beit Arieh (Tel Aviv Univ.) will continue to excavate the Iron Age city.

The site is closed to visitors.

Megiddo

Surrounded by mighty fortifications, equipped with sophisticated water installations and adorned with impressive palaces and temples, Megiddo features some of the most elaborate Iron Age (1200–586 B.C.) architectural remains found in Israel. Its location in the Jezreel Valley, near important military and trade routes, ensured its role as an international battleground in ancient times.

The Song of Deborah (Judges 5) describes a battle won on the outskirts of Megiddo, but in Joshua 17 it is listed among the Canaanite cities not conquered by the tribe of Manasseh. Megiddo became the center of a royal province (1 Kings 4:12) during the reign of King Solomon (965–928 B.C.), who left his stamp on its architecture (1 Kings 9:15). Pharaoh Shishak conquered the city during his campaign against Israel in the days of King Rehoboam (928–911 B.C.); previous excavations found part of a stele that he erected at the site. In 609 B.C., King Josiah of Judah was slain in a battle against Pharaoh Necho’s forces at Megiddo (2 Kings 23:29). The Book of Revelation (16:12–16) aptly reflects Megiddo’s long martial history by designating Armageddon (The Mount of Megiddo) as the site where, at the end of days, the demons will gather the hosts of the nations for the ultimate battle against the forces of God.

In 1996, dig directors Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin (both of Tel Aviv Univ.) plan to investigate the stratigraphy and chronology of the Early Bronze (3150–2200 B.C.) temples, to explore monumental buildings in the lower city during the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.), to study Iron Age stratigraphy and to examine the Assyrian palaces on top of the mound.

The site, a national park, is open daily to visitors for a fee. Guided tours are available.

(See the following BAR articles: Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” BAR 20:01; John D. Currid, “Puzzling Public Buildings,” BAR 18:01; Valerie M. Fargo, “Is the Solomonic City Gate at Megiddo Really Solomonic?” BAR 09:05; Dan Cole, “How Water Tunnels Worked,” BAR 06:02; Yigael Yadin, “In Defense of the Stables at Megiddo,” BAR 02:03.)

Tel Miqne-Ekron

One of the largest Iron Age sites in Israel, Tel Miqne is identified with Biblical Ekron, one of the five capital cities of the Philistines. When the Philistines captured the Ark, they carried it to a number of their cities, including Ekron (1 Samuel 5:10). A powerful, independent city-state, Ekron threatened the indigenous Canaanites and the newly settled Israelites in the early 12th century B.C. For most of the ensuing 600 years, Ekron was a major Philistine political and commercial center. It came under the shadow of the kingdom of Judah in the tenth century B.C., however, and had become a vassal city-state of the Neo-Assyrian empire by the seventh century B.C. In 603 B.C., the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Ekron and with it the last vestiges of Philistine culture.

Excavations under the direction of Trude Dothan (Hebrew Univ.) and Seymour Gitin (Albright Institute), and sponsored by 22 other North American and Israeli institutions, have shed new light on four dramatic chapters in Ekron’s history. The first was the Canaanite settlement of the second millennium B.C.; the second, a large fortified city founded by the Sea Peoples/Philistines in the 12th and 11th centuries B.C., which contained metal and other industries, a large palace and cultic rooms with Aegean affinities. The third occurred in the tenth through eighth centuries B.C., when the city was reduced in size and conquered by the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II in 712 B.C. The fourth took place when the city expanded and became one of the most important olive-oil production centers in the ancient Near East. Excavations of this period have yielded more than 3,000 restorable vessels, a unique assemblage of four-horned altars, inscriptions to the goddess Asherah, five caches of jewelry and silver ingots, and a unique assemblage of Egyptian artifacts, including a golden cobra and a carved ivory tusk with the image of a goddess.

The 1996 season will focus on investigating the development of the Philistine town plan and the growth of Ekron as a major border city in the Iron Age.

Guided tours of the site and of the Miqne Museum are conducted throughout the year by members of the kibbutz.

(See “Prize Find—Golden Cobra From Ekron’s Last Days,” in this issue; Trude Dothan and Seymour Gitin, “Ekron of the Philistines,” in two parts: “Ekron of the Philistines, Part 1: : Where They Came From, How They Settled Down and the Place They Worshiped In” BAR 16:01, and “Ekron of the Philistines, Part 2: Olive-Oil Suppliers to the World,” BAR 16:02; and “Buried Philistine Treasures Unearthed at Tel Miqne-Ekron,” BAR 19:01.)

Nahal Tillah

Located in southern Israel about 15 miles north of Beer-Sheva, the Nahal Tillah project explores Egyptian and Canaanite interaction during the Early Bronze I period (3150–2850 B.C.). Preliminary excavations have already uncovered epigraphic evidence for trade between the two lands, including a clay seal impression and a piece of inscribed pottery with an archaic hieroglyph called a serekh, depicting a temple facade, a falcon and the name of the Egyptian king Narmer (c. 3100–3050 B.C.) In 1996, directors Thomas Levy (Univ. of California, San Diego) and David Alon (Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion) will continue the broad exposure of the Early Bronze I (3150–2850 B.C.) settlement and the examination of the site’s monumental architecture.

The site is open to visitors year round.

Sepphoris

The traditional birthplace of Mary, mother of Jesus, Sepphoris has been continuously occupied from the Iron Age (1200–586 B.C.) to the present. Although the city is not mentioned in the Bible, it is often referred to by ancient Jewish writers, including the first-century A.D. historian Josephus, who testified to the city’s beauty, calling it “the ornament of all Galilee.” The Sepphoris Josephus knew was built in grand style by Herod Antipas (ruled 4 B.C.–39 A.D.). After the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 A.D.), the city became for a time the seat of the Sanhedrin, the central legal and spiritual council of the Jewish people. In about 200 A.D., Sepphoris resident Rabbi Judah Hanasi (Judah the Prince) compiled the Mishnah, the first major collection of rabbinical legal rules and the core of the Talmud. The city continued to serve as an important regional capital until the invasion of the Arabs in 640 A.D.

Finds at Sepphoris include a Roman villa, reservoir, aqueduct and theater; a ritual bath for Jewish inhabitants (dating from the first to fourth centuries A.D.); and a peristyle building with beautiful mosaics (also from the first to fourth centuries A.D.). In 1995, director James F. Strange (Univ. of South Florida) will finish excavating the peristyle structure (possibly a market building) and its associated bath and glassmaking installation.

A national park, the site is open to visitors for a fee from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. daily, and tours are available.

(See the following BAR articles: Ehud Netzer and Zeev Weiss, “New Mosaic Art from Sepphoris,” BAR 18:06; Richard A. Batey, “Sepphoris—An Urban Portrait of Jesus,” BAR 18:03; and “Mosaic Masterpiece Dazzles Sepphoris Volunteers,” BAR 14:01.)

Tanninim

Although Tanninim was occupied from the middle Persian period (fifth century B.C.) to the late Byzantine period (seventh century B.C.), much about this Mediterranean coastal site, which lies 3 miles north of Caesarea Maritima, remains unknown. Only a brief salvage dig has been conducted here, in 1979.

In 1996, director Robert R. Stieglitz (Rutgers Univ.) will initiate this dig by mapping the site’s stratigraphy and determining the extent of large structural remains on the surface of the tell.

Tall al-‘Umayri

When Jephthah subdued the Ammonites, “he smote them … as far as Abel-keramim” (Judges 11:33), whose ruins today constitute Tall al-‘Umayri, a site in Jordan, about 7 miles south of Amman. Occupied from about 3000 B.C. to nearly 500 B.C., the site has been linked with the Ammonite king Baalis (Jeremiah 40:14) and with Pharaoh Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 B.C.). During the Biblical period, the Ammonites used the city as an administrative center near their southern border with the Moabites.

In past seasons, excavators have found an Early Bronze I (3150–2850 B.C.) megalithic tomb; an Early Bronze Age III (2650–2350 B.C.) jar containing more than 4,000 chick-peas; a jar handle stamped with the cartouche of Thutmose III; an 11th-century B.C. casemate defense system with a moat; a late Iron Age (1000–586 B.C.) acropolis and citadel; a Persian administrative complex; and a sixth-century B.C. impression bearing Baalis’s name. Next season, director Larry G. Herr (Canadian Union College) will continue excavating the early Iron Age (1200–1000 B.C.) defenses and settlement and the Persian administrative complex. He will also expand the use of sophisticated technologies, such as advanced sub-surface mapping techniques, the Global Positioning Satellite system (originally used by pilots to locate their aircraft in flight), and the Geographic Information System, which allows researchers to process hundreds of environmental and archaeological facts in seconds.

The deadline for submission of security forms is March 15.

The site is open to visitors on weekdays during the season, but an appointment is preferred. Guided tours are available.

(See Larry G. Herr, “What Ever Happened to the Ammonites?” and BAR 19:06 “The Search for Biblical Heshbon,” BAR 19:06.)

Yatir

After defeating the Amalekites, David shared the spoils with the elders of Judah, including one in Yatir (1 Samuel 30:27). In Joshua 15:48, Yatir is allotted to Judah. The Bible also identifies the site as a Levite town, assigned, along with its pastures, to Aaron and his descendants (Joshua 21:14).

Located among rolling hills about 12 miles southwest of Hebron, Yatir was occupied from the Iron Age through the Middle Ages. Previous excavations have uncovered a Byzantine church and Iron Age pottery. Next season, directors Hanan Eshel (Bar-Ilan University) and Eli Shenhav (Jewish National Fund) will excavate the Iron Age tell and the Byzantine church and will search for remains from the Second Jewish Revolt (132–135 A.D.).