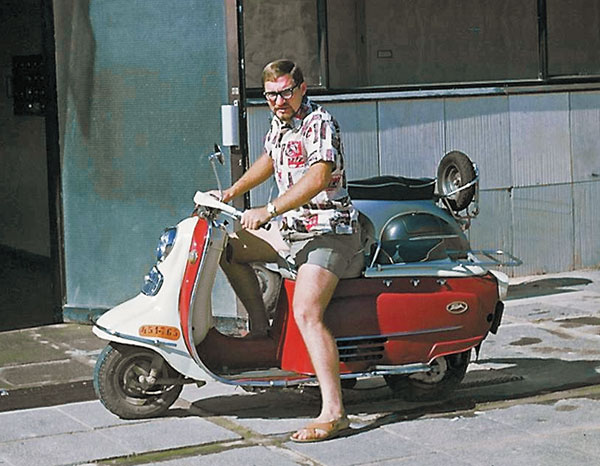

From Vespa to Ashkelon

BAR Interviews Lawrence Stager

050

Lawrence Stager is the Dorot Professor of the Archaeology of Israel at Harvard University and director of its Semitic Museum. Since 1985 he has led the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon. Professor Stager sat down with BAR editor Hershel Shanks to talk about how the field has changed over the past 35 years and what the future holds for Biblical archaeology.

Hershel Shanks: You and I go back to the early 1970s, Larry. When I first met you, you were riding a motorcycle around Jerusalem.

Lawrence Stager: It was a motor scooter—a little thing called a Vespa.

When did you first come to Israel?

1965 was my first year over there. I went with the American Friends of Hebrew University. The classes were partly in English, but we had to go to ulpan [Hebrew classes largely for new immigrants]. We learned ’ivrit qala, simple Hebrew. I found the classes rather boring, so I went to some of the more elevated lectures by Yigael Yadin and other archaeologists. Even when I couldn’t grasp all the Hebrew, from the slides I knew what was going on. So I met some of 052the more famous Israeli archaeologists. Having been a protégé of G. Ernest Wright as an undergraduate here at Harvard gave me an entrée into places I wouldn’t have been able to go otherwise.

In 1972 when you and I met, I’d already been digging at Tell Gezer for five years. It was there that I really got to know field archaeology.

That’s 35 years ago. What have been the big changes in archaeology over the past 35 years?

One of the big changes—and it happened gradually—is that we collect things that were previously neglected or thrown out. For example, fauna, nonhuman bones—what most people call animal bones (but since Darwin, humans should be classified as animals, so “animal bones” is not a very accurate definition of fauna): Fauna are now collected even through fine sieving.

Botanical samples are another example. In the Mediterranean zone they have to be charred to be preserved. But even if you find a charred sample, you have to figure out a method to collect it systematically. An archaeologist in Illinois, Stuart Struiver, working in the state’s archaeology program, developed a water-flotation method that causes a lot of these botanical remains to float to the top; you can then skim them off. But he had nearby rivers and streams for water. We didn’t have that luxury [when I was digging in the desert]. At Tell el-Hesi, we even had to bring in water for drinking. So how were we going to use the flotation method? Robert Stewart, who has worked in Iraq with Robert Braidwood, adapted the plant flotation method to arid environments, first at Tell el-Hesi.

Collecting fauna and botanical samples was a major change in trying to understand the environment in which these ancient people were living: What were their preferences for food? How did they go about processing it? In some cases, this has even helped with cultural interpretation. For example, in the case of the Philistines, it’s now pretty obvious that during the first two centuries after they arrived in the southern part of Canaan, they had a preference for pig. When you go outside the Philistine homeland, you find that’s extremely rare. There you find mostly sheep, goat and cattle.

It isn’t simply whether you have a lot of pig in one region and not a lot in another. What is the explanation for the difference? Some anthropologists want to give it an ecological explanation: Where you have pig, you have to have shade or swampy areas where they can lie in the mud, because they don’t pant and they don’t sweat. (I don’t know where we got the idea of “sweat like a pig”; it seems to be quite the opposite.) So the two best areas for pigs are these coastal areas where you have a certain amount of swampiness and, second, the highlands where the early Israelites lived. There you have evergreen oak, and the evergreen oak is important because it yields the acorn that is a favorite food of pigs. If the explanation for the differential pig consumption were ecological, you would expect to find pig in the highland home of the Israelites. It is ideal for pig raising. That’s why I don’t think the ecological argument works too well. The difference must be cultural.

If I understand correctly, you’re expressing disagreement with your own faunal experts Brian Hesse and Paula Wapnish.

Well, that’s permissible. They’ve done the really hard work of identifying these pigs and their percentages [of total bones]. But I don’t think they’ve dealt with the cultural explanation quite well enough. I think the difference in pig consumption reflects a cultural difference.1

There are other cultural differences between the Philistine areas and the areas of early Israelite settlement. You have locally made Aegean-style monochrome pottery in Philistine areas but not in Israelite areas, even though they are geographically quite near one another. Why doesn’t Lachish have any Philistine monochrome pottery even though it’s only 20 miles from Philistia? Why doesn’t Lachish have pig? It’s because they’re different groups, different cultures.

The collection of this faunal and botanical material enables you to refine your cultural reconstruction of the past. How about the “historical” as opposed to “cultural” reconstruction of the past? Is there a movement in archaeology away from the “historical” and more toward the “cultural” or anthropological?

There are different kinds of history. Cultural history is about lifeways that don’t necessarily make it into the royal records. 053Some call this a form of history “from the bottom up” rather than “from the top down.”

I’ve heard some scholars say they’re interested in “culture” rather than in the “event” that we usually think of as history. The public is often interested in the “event,” especially in Biblical archaeology.

We shouldn’t disregard “events,” but it is important to see them in wider and deeper contexts; for example, how do events intersect with environment, economy or society? In my analysis of the battle hymn known as the “Song of Deborah” (Judges 5), I tried to show how this event between the Canaanites and the early Israelites related to archaeology, ecology and social history.a 2 There are some archaeologists who don’t want to deal with the Bible at all, even though it contains the most important group of texts we have. But I think they’re quite wrong in neglecting these texts, whether they agree or conflict with archaeological data and interpretation.

We also have royal inscriptions [from Egypt and Mesopotamia]. But you have to know how to work with these documents. Egyptians, for example, never lose wars. But does that mean we throw away those royal documents and decrees and don’t try to analyze them for what they might tell us historically? Often embedded in these documents are all kinds of data that may have nothing to do with the intention of the writer or person who is creating these inscriptions. The same thing goes for the Assyrian annals. They are rich with data. And the same thing goes for the Biblical text.

Can you give me an example?

Take the Israelite Conquest. If you look at the Book of Joshua, it’s pretty clear that it is a very fast-moving conquest in the north, the south and in between. German scholars were telling us already back in the 1920s and 1930s that one shouldn’t look just at the Book of Joshua. You’ve got to look at the Book of Judges as well, where the conquest is much more piecemeal.

Or take the Deuteronomistic historian. You must understand the tendencies of the Deuteronomistic historian, how a lot of this material was put together. It’s important to understand the Tendenz of the author or authors. It’s important to understand their objectives and goals and how they used their different sources. There are sometimes sources within sources. And probably sources within sources within sources, if you could trace them back.

There are a number of archaeologists who simply ignore the Bible as a source. A lot of the younger generation are 054tuned into anthropology. They either ignore Biblical material completely or don’t really have the facility or ability to deal with it. I would say it’s a trend, and it has happened largely because many of the archaeologists in Israel, even Israeli archaeologists, are not familiar with Biblical criticism. Some Israeli universities have a very strict separation of the Bible department and the institute of archaeology. This was not so true in the earlier days, in the time of great scholars like Yigael Yadin and Yohanan Aharoni.

It’s also true that many archaeologists working in neighboring lands want nothing to do with the Bible. That attitude is for the most part political. And that is something that works to the detriment of archaeology.

You can say, well, these Biblicists have overdone it [in the past]; these Biblical archaeologists have brought in material that should never have been linked with archaeology. But that reaction [of ignoring the Bible], I think, is too extreme. Many of these Biblical texts are relevant. They give you a more nearly complete picture than you get when you’re just doing archaeology. If the Biblical material is treated with due caution using methods that are appropriate, many things make much more sense.

Are people also downgrading other Near Eastern texts?

Scholars are much more gullible about nonbiblical texts than they are about Biblical texts. They are much more suspicious of Biblical texts. Quite often, if it’s said in an Assyrian annal, it’s taken literally.

All texts must be considered in light of the intentionality of the authors. What are they trying to convey? All of this requires careful analysis. But that doesn’t mean you ignore it.

How did you happen to come to lead the expedition to Ashkelon?b 3

Yigael Yadin invited me to come to the Institute for Advanced Study in Jerusalem to work on the question of the early settlement of the Israelites, which has been one of my major interests. We lived there in 1983–1984, and on weekends I got to know Professor Benjamin Mazar quite well. He would invite me to come to his apartment on Shabbat and we would have a discussion on whatever problems seemed to be important to him. It was never small talk; it was always some historical problem, some archaeological problem. Just the two of us. Mazar was a very creative, I would say extraordinary, Biblical historian.

That was a favorite word of his, “extraordinary.”

And “childish.” If he thought you were really giving up, saying something that is puerile or simply too simplistic for words, he’d just say “childish.” When he said “childish,” you knew you’d better get on to another subject.

We had many wonderful afternoons together. Even when he was in his late 80s, I would refer to something in the Bible and he would say, “Oh that’s here. Oh, my memory is going.” Then he would flip through his Hebrew Bible to the page and point right to the verse. To me, that was always amazing.

I once had the chutzpah to ask him, “When did you write your first major article?” It was in German and his mentor Julius Lewy wanted him to write an article on the Amarna letters [cuneiform tablets from the 14th century B.C.E. found in Egypt]. He wrote that article when he was 19 years old. I stupidly asked him, “Well, could you read Amarna Akkadian?” because it’s considered peripheral Akkadian, more difficult than the standard Akkadian that you get in Mesopotamia. He said, “Well how could I possibly write an article about the Amarna letters and the Amarna period if I didn’t read the Amarna tablets in the original?”

When I was proposing an interpretation of the dog cemetery at Ashkelon, I said, I think it has to do with dogs as healers and there must be some Phoenician deity that was a healing god, and these dogs were an emblem as they roamed about the temple and licked the sores, like poor Lazarus in the New Testament who gets his sores licked by the dogs [Luke 16:19–21]. And I said to Mazar, well, there’s Gula, a deity in Mesopotamia. He said, “Yes there’s Gula in Mesopotamia but don’t forget—in the treaty of Phoenician Baal and Esarhaddon, Gula is mentioned among the deities that are invoked to be a witness to the treaty.” And, you know, he was right. Only once is she mentioned there, but 055he just recalled that reference in an instant, and I was astounded.

He was also great to visit a site; he came to Ashkelon every season. He loved to sit and ask about the latest discoveries and then he would just talk about putting them into context. And he could do it in an incredibly impressive way.

I wish he had written more, but on the other hand, not too many scholars take out ten years and become president [of the Hebrew University].

He was a politician in his way, too.

Oh yes. He certainly was. Some considered him despotic—for example in the way he would run the Archaeological Council. That brings me back to your question about how I came to dig at Ashkelon. In one of our Shabbat talks, we got to discussing Ashkelon, and I had supposed that Ami Mazar, his nephew, would move from [the Philistine site of] Tell Qasile to Ashkelon, so I never even suggested it as a possibility for me, but Mazar did. He said, “Why don’t you think of Ashkelon?” And I said, “Well, I’m happy to think about it.” So I applied for a license.

The year that I applied, however, another team of distinguished archaeologists was also applying. Nobody had applied to excavate there for 60 or so years, since John Garstang was there in 1921, and suddenly two groups wanted to dig in Ashkelon. Anyway, Mazar told me, you must get your application in, when we decided that Ashkelon might be a good place for me to start [my own dig]. He said, you’ve only got five days to do it. I said “What?” How could I possibly put together a proposal for digging for several years and only have five days to do it? He said, “Just do it.” So I went back [to our apartment] and I had to get some clearance here and there, to make sure that our benefactors, Leon Levy and Shelby White, were happy with the site. I also checked with Phil King, the president of ASOR, who brought us together for a major archaeological project. Finally I had to make sure that the University of Chicago, where I was teaching at the time, was on board. After all of those clearances, I had to write up a proposal in record time. It was not a big proposal. It went in and nothing happened for a while.

Each Saturday I would say to Mazar, “I wonder, did you hear anything about our proposal? What’s happening with it?” He said, “No, don’t worry.” But I was quite worried because this was my third time applying for a site, and oh, if this one also falls through, it’s all over for me. Week after week, I would go to Mazar and not hear anything. Finally, I told him that there are groups back at my university who have to know if this is going to go. “If it’s not,” I said, “tell me. I’ll get into something else.” He said, “Don’t worry, I’m sure you’ll get it.” I said, “Well, how do you know?” He said, “Because I’m chairman of the Archaeological Council, that’s how I know.” [laughter] And I got it.

Our first season was in 1985; 15 seasons later we reached the period that I was most interested in: the Philistine period. The key was to treat everybody else’s period with the same concern and care.

One year Mazar came to the site with [Harvard’s] Frank Cross. They were very, very close friends. We all thought, now this is going to be a great opportunity for some of our staff and for me and others to hear these two great scholars talk about the Near East and the Bible. We sat down together, and one couldn’t understand what the other one was saying. They were talking at odds with each other for about a half hour. What one would say, the other one would come up with something that didn’t necessarily follow in the conversation. Well, it turned out that both of them had hearing aids and the batteries were dead in both of them. And so they were trying to think and pretending they heard what the other one was saying, but they weren’t. Once we got them new batteries, then it became a very interesting conversation.

I miss all of those great ones. Now Haim [Tadmor] is gone and [Nahman] Avigad. A few years back Ruth Amiran and David Amiran passed away; they were wonderful friends.

Many of them were at what I call soirees that I attended in later years at Mazar’s apartment on Shabbat afternoon.

Yes, Mazar would hold the salon. They were wonderful. They were always exciting. They had a much broader set of interests than just archaeology. We’ll miss that generation a great deal.

To our readers, Biblical archaeology often seems like an enormously argumentative discipline. Archaeologists 056are sometimes almost derogatory of one another and uncivil. It is not simply a critical exchange of ideas, but enormously contentious. Is that peculiar to Biblical archaeology?

I think there’s much too much of that in Biblical archaeology. But there is quite a bit in other fields too. If you look at the argument over Troy, these two scholars that were at the same university—the historian and the archaeologist (who unfortunately died before he could finish his major work there)—were at each other. I would say that’s as contentious as anything we have in Biblical archaeology.

There’s a whole group that says Homer has nothing to do with the Late Bronze Age and Troy or the Early Iron Age. That group says Homer’s all about eighth to seventh century [B.C.E.]. You had a famous historian like Moses Finley writing The Trojan War: Lost. He was making light of people, archaeologists especially, who felt there was a core of Late Bronze Age archaeology that was embedded in the Iliad—the whole list of ships, for example.c 4

I think if you go into depth in places, even in American archaeology, you’ll find some very heated arguments—for example, about when did humans first arrive here.

In an earlier generation, [Israeli archaeologists] Yohanan Aharoni and Yigael Yadin were always at loggerheads.

Today, the most outspoken one is Israel Finkelstein—a good friend of mine. We have our disagreements, but it has never become ad hominem. I can’t say that has been the way he’s treated some of the other archaeologists for whom I have great respect, including Ami Mazar.d I think Ami Mazar has been much more judicious in his responses to and statements about this question of chronology than Israel has in dealing with Ami Mazar.

What’s the future of Biblical archaeology?

I think there’s a great future for it.

057

Are we “dug” out?

Not really. I would say, Don’t focus just on digging in Israel. For example, the Arameans are up there in western Syria and Turkey just waiting to be revealed. The Israelis can’t dig in Syria, but they can dig in Turkey.

The Phoenicians are another phenomenon that needs to be studied more in Spain and Sardinia and Sicily, North Africa and down the coast of Africa. Of course, much more needs to be done in their homeland, where it’s been very difficult because of the political situation, the military situation.

You mean in Lebanon.

Yes. In Tyre, Sidon, places like that.

As I understand it, the original Phoenicians were Canaanites.

“Phoenician” is simply a technical term for what the Greeks called them. The Phoenicians, as we know them in the Iron Age, didn’t call themselves Phoenicians at all. They called themselves Canaanites—Canaani. The term is still being used by some lonely Phoenicians in the time of St. Augustine [fourth–fifth century C.E.] in North Africa.

They call themselves Canaani?

In the New Testament you hear of Simon the “Canaanite” [Mark 3:18=Matthew 10:4] and the “Canaanite woman” in the district of Tyre and Sidon [Matthew 15:21–22], so they’re still using that term at that time. In the Hebrew Bible, though, Canaani becomes a rather derogatory term because it’s a trader or a merchant. And the Israelites, being more agrarian in this respect, thought that wasn’t exactly the way you should make your living. The Hebrew word rokel, “merchant,” has a cognate rakil that means “slanderer” or, according to Eduard Lipinski, “swindler” (see Jeremiah 6:28, 9:3 [English 9:4]). So all these terms for merchant are really terms of disparagement. The Greeks did the same thing. They used the term “Phoenicians,” but they said, “Oh, they’re just carrying trinkets around the Mediterranean.” Well, of course, from our shipwrecks we know they were carrying much more than trinkets.5

Is there still room for American archaeologists in Israel?

In the last 35 years we’ve seen Israeli archaeologists come of age, so that now you have so many competent archaeologists digging all over the place.

Foreigners—that is non-Israelis—can still make some contributions. But it’s not the same as in times past when there were a tremendous number of foreigners digging there, when the core of Israeli archaeologists was much smaller.

You still find this in neighboring countries. This tends to breed a kind of colonial condescension of outsiders to the native, indigenous archaeologists. In many of these places, they haven’t built up a cadre of really good archaeologists to change this perception. A lot of Americans or Canadians or European archaeologists like to go to those countries because they still “rule the roost,” or determine the direction of research. But this changed rather dramatically in Israel in the 1960s and 1970s. The maturing of Israeli archaeology developed in such a way that you have to be there all the time to keep up with all the discoveries that are happening so fast. Now, it’s almost impossible to absorb all the new data that’s coming out.

So much data with reams of details that’s being published today: I just wonder if it’s going to be useful in its raw state. I see you shaking your head in agreement. I wonder if we’re producing data that is not meaningful or useful.

It may be in a lot of cases. But whenever you’re dealing with history, you are trying to find new sources of data. You’re actually retrieving things that may be considered useless, but tomorrow there may be methods of making them useful.

The most important thing is that you have a specific problem you’re trying to solve or an issue you’re trying to address. Then you look for data that might help you address that problem.

For example, I’m very intrigued right now with the question of tribalism in ancient Israel. The problem is also there with the Arameans (if we ever get a better understanding of their kingdoms). Part of the problem of those who want to deny a Davidic or a Solomonic state in Israel is their misconception of what an ancient state was. It’s not our modern state, like states in the 19th/20th century. We can see that today in places like Afghanistan and Iraq. These “states” are impositions on cultures that were not amenable to state constructs. We’ve got to redefine what a “state”—I prefer “kingdom”—is. 058Then we’ll come to a much better understanding of what the society was that David and Solomon actually headed.

Judah is called Beit David, the House of David. Israel [the northern kingdom] is called Beit Omri, the House of Omri, according to an Assyrian inscription. Beit indicates a dynasty. There were a lot of these kingdoms that were viewed as large households in which the king sat there at the top of the house, the patriarchal father, as it were, of his family. Down lower were different levels.

What I detect is that tribalism is never excluded or extinguished by state formation in the Ancient Near East. Even after kingship is established, these bonds of kinship, clans, lineages, tribes persist. They don’t always make it into the court literature because that’s not what they’re writing about. They’re interested in the kings and the courts, but the persistent tribalism is there nevertheless. This aspect of society is often represented by a council of elders. It’s interesting how councils of elders pop up at different times, even in the seventh and eighth centuries [B.C.E.]. They sometimes determine who is to be king, as in the case of Josiah [2 Kings 21:24]. The ‘am ha’aretz [literally, “the people of the land”] decide who the next king is going to be. The Samaria ostraca too often reflect old clan and tribal names and sub-divisions. The old tribes were always a problem. When these people presented the wine or oil to the king, you think of them as little subdistricts, but this never worked out. They were never organized as coming from different districts with boundaries. They were organized around figures who were important in their lineage. And the lineage can transcend geographical demarcations. The so-called “L-men” of the Samaria ostraca were not tax collectors for different districts, but notables representing various clans in and about the capital city, Samaria. On behalf of their respective clans or lineages, they delivered vintage wine and extra-virgin olive oil to the king’s table.6

Even in Ezekiel’s early-sixth-century [B.C.E.] vision of the utopian land, tribes receive equal allocations of this renewed Israel (Ezekiel 47–48). I don’t think you would use this tribal language if tribalism weren’t still alive and well in the minds of many of the people who are hearing these stories.

One of the things I’m studying now—and I hope to do a book on it—is to show how the tribalism of the Iron I period, the period of the Judges, continues right on until the end of Judah. What is Judah but a big tribe? Sometimes the tribalism is suppressed. Other times this tribalism moves toward the surface. In a lot of the court literature, it doesn’t come through because they’re not interested in those tribes who can also make a lot of trouble.

One of the great fallacies is linking tribalism exclusively to nomadism. It isn’t. Villagers can be tribally organized. City dwellers can belong to different tribes. In modern Iraq that’s the case. It’s even more so today in Afghanistan. When you look at it that way, then you understand how these Biblical people understood themselves. They didn’t identify primarily by place, as you would if you were a city-state dweller without a tribal organization. Most telling is the response from the Israelites that Absalom, the rebellious son of King David, received at the city gate into Jerusalem. He asked them each, “From what city are you?” And he received the answer, “Your servant is of such and such a tribe of Israel” (2 Samuel 15:2). By tribal identification, you know who your ancestors were. Genealogy plays a key role in locating yourself in society. That’s why genealogies are so important in the Bible. These people codified their collective memory and history in genealogies. The concept of tribalism can be extremely fruitful in looking at not just the Bible but other ancient texts as well, and in addressing anthropological issues. It’s perfectly valid for groups of people to organize themselves in tribes. This usually ends up with similar kinds of consequences. You end up with violence and honor. Honor becomes very important—honor and its opposite, shame. They are also moderately violent because they are confrontational: It’s my brother and I against our cousin. Yet it still remains generally in the family, so it’s a feud. You also get collective responsibility. In the Bible that’s the blood vengeance (Hebrew, naqam; see Judges 16:28) that certain lineages make against those whom they consider have 078violated the rules of tribal organization. This is found all through the Book of Judges, for example.

My biggest problem right now in tackling this subject is to figure out ways that archaeology can also help inform the reconstruction.

Can you talk a little about the profession’s relationship to the public?

Well, I think that’s where your magazine has done a terrific job, and I hope it continues for eons and eons. We need something like that to convey the profession to the public.

Is the public too fixed on what the archaeologists tend to denigrate as relics?

You like to see artifacts, there’s no doubt about it. People still think that’s what we dig for: the museum pieces. If that’s what we dig for, however, we don’t yield very much. Your friend [collector] Shlomo Moussaieffe once said, “The thieves discover all the nice things. The archaeologists don’t know where to dig.”

Is it true?

It depends on whether you’re defining archaeology as finding nice things. We do find a few, like the silver bull from Ashkelon.f

Thank you very much, Larry.

Lawrence Stager is the Dorot Professor of the Archaeology of Israel at Harvard University and director of its Semitic Museum. Since 1985 he has led the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon. Professor Stager sat down with BAR editor Hershel Shanks to talk about how the field has changed over the past 35 years and what the future holds for Biblical archaeology. Hershel Shanks: You and I go back to the early 1970s, Larry. When I first met you, you were riding a motorcycle around Jerusalem. Lawrence Stager: It was a motor scooter—a little thing called a Vespa. When did […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1.

See Lawrence E. Stager, “The Song of Deborah: Why Some Tribes Answered the Call and Others Did Not,” BAR 15:01.

2.

See Lawrence E. Stager, “When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR 17:02; “Why Were Hundreds of Dogs Buried at Ashkelon?” BAR 17:03; “Eroticism and Infanticide at Ashkelon,” BAR 17:04.

3.

See Edwin M. Yamauchi, “Historic Homer—Did It Happen?” BAR 33:02.

4.

See Hershel Shanks, “Radiocarbon Dating,” BAR 31:01.

5.

See Hershel Shanks, “Magnificent Obsession: The Private World of an Antiquities Collector,” BAR 22:03.

6.

See Lawrence E. Stager, “When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR 17:02.

Endnotes

1.

See Lawrence E. Stager, J. David Schloen and Daniel M. Master, eds., Ashkelon 1: Introduction and Overview (1985–2006), The Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2008), pp. 541–568.

2.

See “Archaeology, Ecology, and Social History: Background Themes to the Song of Deborah,” in J.A. Emerton, ed., Congress Volume: Jerusalem, 1986, Vetus Testamentum Supplement 40 (London: Bell, 1988), pp. 221–234; “Yigael Yadin and Biblical Archaeology,” in Joseph Aviram, ed., In Memory of Yigael Yadin, 1917–1984: Lectures Presented at the Symposium on the Twentieth Anniversary of His Death (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2006), pp. 13–27.

3.

See Stager, Schloen and Master, Ashkelon 1, pp. 215–323; Lawrence E. Stager, Ashkelon Discovered: From Canaanites and Philistines to Romans and Moslems (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1991); Lawrence E. Stager, “Ashkelon,” in Ephraim Stern, ed., The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (NEAEHL), vol. 1 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993 [English]), pp. 103–112; “Ashkelon,” in Ephraim Stern, ed., NEAEHL, vol. 5, Supplementary Volume (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2008), pp. 1578–1586.

4.

“Yigael Yadin and Biblical Archaeology,” pp. 13–27; Joachin Latacz, Troy and Homer (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004).

5.

Stager, “Phoenician Shipwrecks and the Ship Tyre (Ezekiel 27),” in John Pollini, ed., Terra Marique: Studies in Art History and Marine Archaeology in Honor of Anna Marguerite McCann (Oxford: Oxbow, 2005), pp. 238–254.

6.

Philip J. King and Lawrence E. Stager, Life in Biblical Israel (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), pp. 302–314.