What’s in a name?

That question has many answers when it’s applied to the Bible.

In the Bible’s beginning, in the story of creation, names provide literary analogies or connections. For example, ’adam in Hebrew means both “person” (Genesis 1:26–28) and “man” (Genesis 2:5–4:1). As the name of the first man, it suggests a generic person, or everyman. It’s not until Genesis 4:25 that Adam is used as the name of a particular human being.1

Moreover, the word ’adam sounds almost exactly like the word for “ground,” ’adamah. In Genesis 2:7, God forms man from the ground, ’adam from ’adamah. And in Genesis 4:17, God curses the ’adamah because ’adam disobeyed God’s command. The Bible contains many examples of similar wordplay.

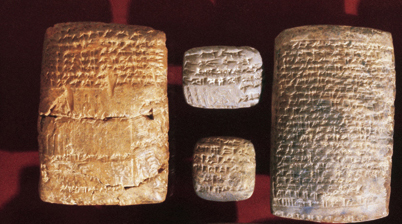

Throughout the Bible, names also provide clues to people’s origins or ethnicities. From the third through the first millennium B.C.E., inhabitants of the Levant spoke and wrote a wide variety of languages. Old Akkadian, for example, dates from the third millennium B.C.E., as does Eblaite, the language of Ebla. Amorite, one of the languages labeled West Semitic (or Northwest Semitic), has survived only in ancient personal names; it dates from before 2000 B.C.E. through the middle of the second millennium B.C.E. Ugaritic dates to the late second millennium B.C.E. Hebrew, another West Semitic language, dates to the first millennium B.C.E. Other West Semitic languages from the first millennium B.C.E. include Hebrew, Aramaic, Phoenician, Punic, Ammonite, Edomite and Moabite. And that’s not including East and South Semitic language groups.

During the past century, scholars have collected and studied thousands of personal names from these and other ancient Near Eastern languages. Most contain either specific root words or grammatical structures characteristic of a known language. As a result, scholars can identify the ethnic groups of certain biblical characters based on their names. Sometimes, the biblical identification of a character’s ethnicity is authenticated; sometimes, as we shall see, the date of composition for a particular Bible passage is suggested—simply through names.

Think of it this way. Archaeologists can date the layers, or strata, of their excavations from the pottery sherds uncovered in those layers. Just as the shape and decoration of pots change over time and from place to place, so also do names. The changes in pottery types and in language usage have enabled archaeologists and scholars to construct very refined and sophisticated pottery typologies and personal name typologies.

Most of the names in the Bible appear in other ancient Near Eastern texts. Often these names contain some elements that do not appear over many time periods. These provide scholars with significant clues as to what time period the names come from.

For example, take the name Adam again. Similar names can be found in third-millennium B.C.E. Old Akkadian and Eblaite.2 Several personal names spelled like Adam also occur among Amorite names of the early second millennium B.C.E.3 From the 13th century B.C.E., Adam appears as part of the name of a god and a month.4 After the Israelite monarchy (first millennium B.C.E.), the name does not appear outside the Bible, except maybe as part of two Punic personal names.5

Thus, Adam was only used as a personal name in the earliest collections of West Semitic names. This suggests that the creation story originated at least by the second millennium B.C.E., probably in the Amorite world.

But just as one sherd cannot be used to date an entire stratum, so we should be cautious in dating a text on the basis of a single personal name. After all, our knowledge of personal names, extensive as it is, is by no means exhaustive. Tomorrow some archaeologist might uncover a Hebrew inscription from the first millennium B.C.E containing the name Adam.

So we examine the names of other biblical characters who appear in the Adam stories. Eve is the most obvious choice. Her name seems to have come from a West Semitic root meaning “to live.” Alas, this root appears in names from every period.

Fortunately, in Genesis 5, where Adam occurs as a personal name in a genealogy, there is a whole list of other names to check. Some, like Lamech and Enosh, do not appear outside the Bible. So they’re no help. Others—like Seth, Mahalel and Jared—appear in too many time periods, like the name Eve, and are no help.

This leaves only Kenan, Enoch and Methuselah. The first two names have extrabiblical connections but cannot be used for dating purposes. Kenan has the same root as Cain, which appears in South Arabian personal names in the first millennium B.C.E. However, we have no South Arabian texts from before then, so we do not know if those names were used in the second millennium B.C.E. The problem with the name Enoch is more complicated. Genesis 4:17 relates that Cain named the first city, which he founded, after his son Enoch. Traditionally, a city in Mesopotamia called Uruk is considered one of the oldest cities. The Sumerian name for Uruk, UNUG, is the city’s earliest attested name. However, since we do not know when UNUG became the city’s name, even if it is a version of the name Enoch, we cannot use it to date the genealogy. It could have been borrowed at any time over the millennia.

The name Methuselah alone is free of any of these difficulties. One of its two elements, “methu,” which is similar to the West Semitic “mutu,” meaning “person” or “husband,” only occurs in West Semitic personal names from the second millennium B.C.E. It appears in Amorite, Ugaritic and Canaanite personal names.6

The name Methuselah, then, bolsters the argument for a second millennium B.C.E. source for the names and perhaps for the early chapters of Genesis. A similar analysis of the names in Cain’s genealogy in Genesis 4:17ff. refines this estimate to the early second millennium B.C.E.7 Names such as Jabal, Jubal and perhaps Tubal-Cain have roots that occur in personal names from this earlier period. None of these West Semitic names is known to occur in the first millennium B.C.E. (with the root behind Cain and Kenan forming the sole exception). Without going into all the details here, some of the names in the genealogies in Genesis 4 and 5 date no later than the second millennium B.C.E. Further study suggests that all 42 personal names in Genesis 1–11 can fit into this period.8

On this basis, we can conclude that the material found in the first 11 chapters of Genesis—from the creation to the birth of the first Hebrew, Abraham—has a source in the early second millennium B.C.E. This does not necessarily prove that the people in these stories were real, historical people. It means only that the traditions that lie behind the text go back to the early second millennium B.C.E.

Kenneth Kitchen, of the University of Liverpool, has already analyzed the personal names in the patriarchal narratives (Genesis 12–50) for BAR readers,a so I won’t reiterate that evidence here.

In the Book of Joshua, dated according to the biblical chronology to the Late Bronze Age (16th-12th centuries B.C.E.), the many Israelite names are less helpful than the non-Israelite names in the search for the material’s possible sources. Twelve non-Israelites are mentioned almost incidentally—eight with West Semitic names. The other four names resemble Hurrianb names.9

Some of the West Semitic names contain roots that appear in names from many periods. For example, Horam, the name of the king of Gezer (Joshua 10:33), incorporates the Hebrew word for mountain (har), found in names throughout the ancient Near East.

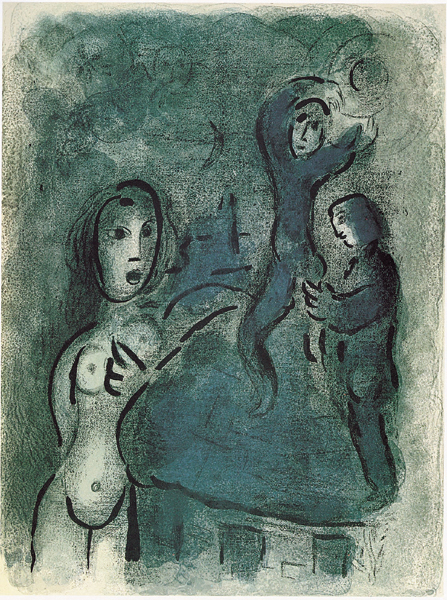

Or consider Rahab, the harlot in Canaanite Jericho who, in Joshua 2, saves the Israelite spies from capture. Rahab’s name contains the West Semitic root

Though these two West Semitic names—Horam and Rahab—and the other six non-Israelite West Semitic names appear in more than just Late Bronze Age material, seven of these eight names are attested to in extrabiblical records from the Late Bronze Age. This suggests that these names in Joshua and perhaps the stories in which they occur originated at that time.

The four Hurrian-type names—Hoham, king of Hebron, and Piram, king of Jarmuth (Joshua 10:3); and Sheshai and Talmai, sons of Anak from Hebron (Joshua 15:14)—are of greater significance. The cultural and linguistic origins of the Hurrians have been found north of Canaan from the end of the third millennium B.C.E. The Nuzi tablets, a cuneiform archive from the 15th century B.C.E. found in the north Syrian city of that name, preserve a strong Hurrian cultural influence. In Canaan, a cuneiform tablet discovered at Hebron may contain a Hurrian name.10 Many citizens of Late Bronze Age Syrian cities, like Ugarit and Alalakh, had Hurrian names. By the Late Bronze Age, Hurrian peoples had established the kingdom of Mitanni in northern Syria. However, Hurrian and West Semitic populations intermingled in the Late Bronze Age throughout the Levant.

The Hittites conquered the Hurrians in the 14th century B.C.E., but the Hurrian language and culture, including personal names, did not disappear until the end of the tenth century B.C.E.c So when we come across a Hurrian name, we know it dates no later than the second millennium B.C.E. We can be even more exact in our dating of the Hurrian-type names in Joshua since they closely parallel Hurrian names of the Late Bronze Age.11

Though some scholars have suggested that the names of the well-known individuals listed in the genealogies in Genesis 1–11 might have been preserved by a variety of Israelite sources and incorporated into the text by later editors, this theory does not hold for the characters with Hurrian-type names in Joshua. These individuals, unlike the patriarchs, play only incidental parts in what is essentially another people’s history—the Israelite’s history. They are not heroes. They are not Israelites. There was no reason to preserve these individuals’ names and add them later to biblical stories. If these stories were composed in the first millennium B.C.E., surely the non-Israelite names would be from the first millennium B.C.E. They are not. Instead they are from the second millennium B.C.E.

Several biblical names have been found in extrabiblical sources from the first millennium B.C.E., however. The most recent example is the Tel Dan stela with its startling reference to the House of David.d

Biblical names from the United Monarchy (1000–930 B.C.E.) sometimes even tell us about their bearers’ religious affiliations. The names often contain a divine element that the Bible preserves in shortened form (or omits entirely, as in the premonarchic name Rahab). The name of Jeremiah’s scribe, for example, is given as Baruch in the Bible, but as we know from his seal, which has survived in two separate bullae,e his complete name was Berechyahu. Baruch means blessed; –yahu is a form of Yahweh frequently used in personal names. So his full name means “blessed of Yahweh.” Baruch’s father is named Neriah in the Bible. Neriah preserves the divine element in another shortened form—iah or YH, which stands for Yahweh in Hebrew. Baruch’s seal identifies his father as Neriyahu.

Yahweh- and El-names predominated in the kingdom of Judah. El, incidentally, is a more generic term for a deity; Yahweh is the Israelite God’s personal name. Evidence from the many seals and bullae that have been recovered from the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. reflects the populace’s devotion to Yahweh, at least in the naming of their children.

In the northern kingdom of Israel people also used Baal-names, like Baalzakar (b‘lzkr) and Abibaal (‘bb‘l), as attested to in the Samaria ostraca of the eighth century B.C.E. However, Baal can be used like El to refer to any deity, including Yahweh, and not just to the pagan god with that name.

During the Divided Monarchy (931–586 B.C.E.), many biblical rulers are attested to in extrabiblical Hebrew sources and in Egyptian, Aramaic, Assyrian and Babylonian sources. Many non-Israelite rulers mentioned in the Bible are attested to in the same extrabiblical records that mention the biblical rulers of Judah and Israel. Assyrian texts refer to Judah’s leaders Ahaz, Hezekiah and Manasseh, and to Israel’s Omri (as a dynastic founder), Ahab, Jehu, Joash, Pekah and Hoshea. Babylonian sources list the last kings of Jerusalem—Jehoiakin and Zedekiah.

Interestingly enough, none of the extrabiblical sources has yielded the name of an Israelite or Judahite king not mentioned in the Bible.f

This article illustrates only some of the ways personal names are significant to biblical studies. I am not suggesting that the names prove the historical claims of the biblical accounts in which they appear. Personal names are only one witness. A great deal of other evidence must be considered and weighed before questions of historical accuracy can be decided. But names often provide important evidence for dating the biblical writers’ sources.

As we have seen, personal names suggest an early second millennium B.C.E. Amorite origin for the names in Genesis 1–11. Understanding the meaning of biblical names also enriches our understanding of the whole text, as in the case of Adam’s name. Names sometimes reflect ethnicity, as might the Late Bronze Age Hurrian names preserved in the Book of Joshua. Names sometimes also reflect the religious affiliations of the bearers or their parents, as do the Yahweh-names from the United Monarchy. And sometimes, names can correlate biblical and extrabiblical records, each confirming the other, as in the case of the rulers’ names from the Divided Monarchy. So if you still ask, What’s in a name? My answer is, Lots.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Kenneth Kitchen, “The Patriarchal Age: Myth or History?” BAR 21:02.

The Hurrians were a non-Semitic people who appeared in northern Syria early in the second millennium B.C.E.

One of the latest names is another Talmai, in this case referring to the king of Geshur and father-in-law of David (2 Samuel 3:3, 13:37; 1 Chronicles 3:2). See Timothy Renner, Moshe Kochavi, Ira Spar and Esther Yadin, “Rediscovered! The Land of Geshur,” BAR 18:04.

See Hershel Shanks, “‘David’ Found at Dan,” BAR 20:02; David Noel Freedman and Jeffrey C. Geoghegan, “‘House of David’ Is There!” BAR 21:02; Anson Rainey, “The ‘House of David’ and the House of the Deconstructionists,” BAR 20:06; and Philip R. Davies, “‘House of David’ Built on Sand: The Sins of the Biblical Maximizers,” BAR 20:04.

Bullae, lumps of clay used to seal documents, are often stamped with the sender’s official seal. See, for example, Hershel Shanks, “‘Signature’ of King Hezekiah’s Servant Recovered,” BAR 01:04.

An exception may be Ashyahu, the name of an Israelite king on a recently published ostracon (see Hershel Shanks, “Three Shekels for the Lord,” BAR 23:06).

A number of nonroyal biblical personages are also attested to in seals and bullae. See Tsvi Schneider, “Six Biblical Signatures,” BAR 17:04; Aharon Kempinski, “Jacob in History,” BAR 14:01; Hershel Shanks, “Jeremiah’s Scribe and Confidant Speaks from a Hoard of Clay Bullae,” BAR 13:05 and Josette Elayi, “Name of Deuteronomy’s Author Found on Seal Ring,” BAR 13:05.

Endnotes

Richard S. Hess, “Splitting the Adam: The Usage of ’ADAM in Genesis I-V,” in John E. Emerton, ed., Studies in the Pentateuch, Vetus Supplementum XLI (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1990), pp. 1–15.

Hess, Studies in the Personal Names of Genesis 1–11, Alter Orient und Altes Testament 234 (Neukircher-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1993), pp. 59–69. Examples from Old Akkadian include a-da-mu and a-dam-u. Examples from Ebla include a-da-ma, a-da-mi and a-da-mu. See Ignace J. Gelb, Glossary of Old Akkadian, materials for the Assyrian Dictionary 3 (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1957), p. 19; G. Pettinati, Catalogo dei testi cuneiformi de Tell-Madikh—Ebla, Materiali epigrafici de Ebla 1 (Naples: Istituto universitario orientale, 1979), nos. 238, 929, 1671, 4966 and 5043.

Hess, Names, pp. 60–61. Examples from Manana include a-da-ma-nu, from Chagar Bazar—a-da-mu, and from Dilbat—a-dam-te-lum. See M. Ruttøn, “Un Lot de Tablettes Manänä,” Revue d’assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 54 (1960), text 19, lines 19ff.; text 28, line 12; C.J. Gadd, “Tablets from Chagar Bazar and Tell Brak,” Iraq 7 (1940) 35, occurrences 989 and 995; and J.E. Gautier, Archives d’une famille de Dilbat au temps de la première dynastie de Babylone 26 (Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale du Caire, 1908), text 31, line 6.

Hess, Names, p. 62. The divine name is da-dam. The month name is da-dam-ma-te-[ri]. See Daniel Arnaud, Textes sumériens et accadiens: Recherches au pays d’AsEtata Emar VI.3, Recherche sur les Civilisations, no. 18 (Paris: A.D.P.F, 1986), pp. 116 (text 110, line 38) and 451 (text 465, line 2).

Hess, Names, pp. 61–62. The names are mlk’dm (“Adam is king”) and ‘bd’ dm (“servant of Adam”). See Corpus inscriptionum Semiticarum ab academia inscriptionum et litterarum humanorum conditum atque digestum, Pars Prima Inscriptiones Phoenicias Continens 1 (Paris: C. Klincksieck, 1881), p. 367, text 295, line 4; J.-B. Chabot, “Punica,” Journal asiatique 10 (1917), p. 54, text Costa 21, line 2. Both names are Punic, a late dialect of Phoenician, with inscriptions dating from the fifth century B.C.E. to the sixth century C.E. Adam is used as the name of a god in forming these two personal names. The letter “d” in the first name is not clear so the only certain example is the second one. Adam was also read as a personal name in one of the Arad ostraca from southern Judah. However, the first letter must be restored. As a result, André Lemaire suggested the more likely restoration of a “q” and read the name as qdm, “Qiddem.” Anson F. Rainey, ed., J. Ben-Or, trans., Arad Inscriptions (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), p. 68; and André Lemaire, Inscriptions Hébraïques I: Les Ostraca, Littératures anciennes du proche-orient 9 (Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1977), p. 206.

Hess, Names, pp. 44–45. Examples from Amorite include the personal name from Mari, mu-tu-dda-gan; from Ugaritic, the personal name mtb‘l (pronounced as Mut[u]baal), and mu-ut-dIM (pronounced either Mut[u]baal or Mut[u]addu), the name of the 14th-century B.C.E. leader of Pella. See J.-R. Kupper, Correspondance de

See Hess, “Non-Israelite Personal Names in the Book of Joshua,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 58 (1996), pp. 205–214; and Joshua: An Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press, 1996), pp. 29–30.

Moshe Anbar and Nadav Na’aman, “An Account Tablet of Sheep from Ancient Hebron,” Tel Aviv 13–14 (1986–1987), pp. 3–12.

The parallels between the biblical names and the Late Bronze Age Hurrian names are as follows: Hoham—hhm (Joshua 10:3)/

Hoham and Piram both have a final –am suffix that is not part of the Hurrian element. See Gelb et al., Nuzi Personal Names, Oriental Institute Publications 57 (Chicago: University Press, 1943), p. 217.