God Before the Hebrews

Treasures of Darkness goes back to the Mesopotamian roots of Biblical religion

018

What, if anything, can we learn about Biblical religion from the vast quantities of material relating to Mesopotamian religion? The answer is: a great deal. No single volume provides better evidence for this conclusion than the recently published and widely acclaimed book by Thorkild Jacobsen, The Treasures of Darkness—A History of Mesopotamian Religion.a

Jacobsen is the revered master-scholar of ancient Sumer and Assyria. At 75, he has had an enormously fruitful and prolific scholarly life. Treasures of Darkness is a moving distillation of Jacobsen’s sensitive understanding of Mesopotamian religion.

But this book is not directed to a Biblical audience. Jacobsen has not set out to demonstrate what a study of Mesopotamian religion can teach us about Biblical religion, although he sometimes makes references to similarities and parallels. His primary concern is with the civilizations he has spent a lifetime studying.

Yet the resonances are there. Much of ancient Mesopotamian religion is reflected, although in a perhaps refined form, in later Israelite religion. In a sense, the Israelites can be said to have taken the religious torch from early Mesopotamian religions. To these they of course added their own unique contribution. But many of the abstract attributes of the divine were already in place, developed in Sumerian and Assyrian civilizations of the fourth, third and second millennia B.C.

In 1980, Jacobsen was the recipient of the prestigious George Foote Moore Award conferred at the gala centennial celebration of the Society for Biblical Literature. Why was a Sumerologist/Assyriologist getting an award from the Society for Biblical Literature? The citation accompanying the award recognized that Jacobsen’s “area of major concentration has been outside Biblical scholarship!. Nevertheless,” the citation continued, “he has brought immense riches and value to the field of Biblical research.” In Treasures of Darkness, he makes these immense riches, at least as they relate to Mesopotamian religion, available in a popular and understandable format.

Jacobsen traces three major stages in the development of Mesopotamian religion, corresponding, conveniently enough, to the fourth, third, and second millennia B.C. Each of these three stages reflects a different social and political milieu, which in turn resulted in a different religious orientation.

The earliest Mesopotamian myths provide the keys to understanding the world of the fourth millennium B.C. Compared to later periods, the fourth millennium was a relatively peaceful time during which political power was diffused. Naturally, there were occasional threats to the peace and even military confrontations, but this was not the norm. Sumer was ruled by an ad-hoc, crisis-determined assembly which met at Nippur and conferred offices for the duration of the occasional emergencies.

Gradually all this changed during the third millennium B.C. Conditions then were more accurately reflected in the surviving epics, rather than in the myths. War became the common condition. The “temporary” rulers of the broadly based crisis assemblies of the fourth millennium were replaced by more permanent rulers who were needed for their societies to build massive city walls, erect large public buildings for the administration of the bureaucracy, and raise standing armies to guard the city and defend it. In the third millennium, popular assemblies faded into the background. In their place royal rule developed and was 020institutionalized. Gradually these new kings extended their rule over increasingly vast areas.

In this setting the religious concepts of the fourth and third millennia differed widely. One way to understand the central religious concern of each period is to ask what the central fear of the age was: in the fourth millennium, characterized by a relatively primitive economy, it was the fear of famine, of not having enough food; in the third millennium, it was the fear of war.

This social setting had major implications for the development of religious consciousness in both periods. In the fourth millennium the attitude toward the divine was one of awe at first perceiving the will behind natural phenomena. The gods were seen as kings and lords of their city, guarding it against attack from without and against corruption from within.

In the fourth millennium, worship centered on the numerous powers that dwelt in natural phenomena and were vital to human survival. These powers were experienced as intransitive (not reaching beyond the phenomena in which they were perceived). Because there was a variety of natural phenomena, religion took a pluralistic, polytheistic form. The cult revolved around ways to ensure the presence and protection of powers beneficial to the early economies, and the absence of harmful ones. Various families of Sumerian gods corresponded to the ecological conditions prevalent in their home areas. There were, for example, gods of the marsh and gods of the pastureland.

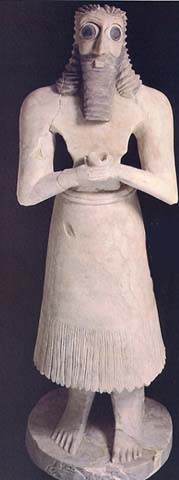

By the third millennium, however, the human metaphor for the gods had become predominant: the gods were seen as rulers rather than as the natural phenomena themselves. The divine was more often conceptualized in anthropomorphic terms, as super ruler.

The change, however, was gradual rather than abrupt. Beginning in the Early Dynastic period (end of the fourth millennium) the non-human forms of the divine began to recede, becoming emblems, and even, at times, enemies of the newer anthropomorphic god.

The Sumerian cult of Dumuzi typifies Mesopotamian religion in the fourth millennium-both in the religious metaphors that define it and the social and political conditions to which it relates. Dumuzi is basically an “intransitive” figure, the élan vital in nature. Indeed, originally there were several distinct Dumuzi figures—Dumuzi of the date palm, Dumuzi of the shepherds, Dumuzi of the grain, and the allied figure of Damu, the power in the rising sap. As economies grew more complex, several of these distinct manifestations of Dumuzi, characteristic of the early economies, were amalgamated.

Literary texts dealing with Dumuzi are relatively abundant. They focus on the great cycle of the year. In some texts, the passing of the fertile spring into the hot, dry summer is represented by Dumuzi’s death. Other texts relating to Dumuzi’s death include simple laments by Dumuzi’s wife, mother and sister. Myths describe the search for the lost Dumuzi, a search that ultimately proves successful: he is found. Other texts have a ritual background: they describe the courtship and marriage of Dumuzi. In the “sacred marriage,” Dumuzi, the power for fertility and yield, is “married” to Inanna, who represents the power of the storehouse. The powers of nature are thus humanized in order to satisfy the need for a meaningful relationship with these often uncontrollable powers.

In the complex tale of “Inanna’s descent,” Inanna is trapped in the netherworld. The forces imprisoning Inanna agree to release her on the condition that she provide a substitute. In her anger that Dumuzi has not mourned her “death,” she names Dumuzi, thus dooming him to the netherworld. Inanna is revived and Dumuzi is doomed to the netherworld in her stead. (Ultimately Dumuzi is rescued for half of each year by his sister’s descent to the netherworld in his place.) Jacobsen explains this involved story as a mythic perception of the relationship between the food in the storehouses and the plants and animals killed to provide this food. The revival (replenishing) of community storehouses is at the expense of the living plants and animals (represented by Dumuzi), which must be 021killed to replenish the stores.

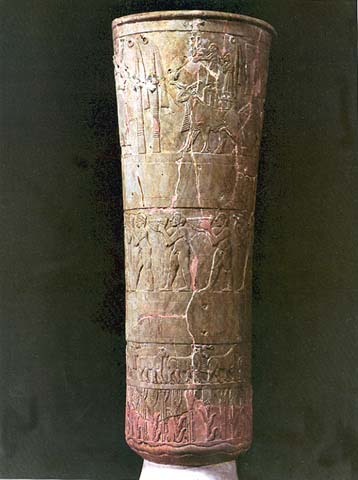

The Dumuzi cult was not confined to the fourth millennium. Indeed, much of the literary evidence by which we reconstruct the Dumuzi cult is considerably later than the fourth millennium. But there is enough evidence to reflect its fourth-millennium origins, including the great Uruk vase, dating to that period, which depicts the sacred marriage between Dumuzi and Inanna.

Dumuzi himself survived, however, even into the first millennium, under the name Tamuz. In one of Ezekiel’s visions the prophet sees the women of Jerusalem—even at the gateway of the Lord’s temple—sitting and wailing for the death of Tamuz (Ezekiel 8:14), not much differently than the women of Sumer wailed 2,500 years earlier.

If the threatening power of nature was the dominant concern of the fourth millennium, the threatening power of man was the dominant concern of the third millennium. The archaeological record reveals that wars and military raids became commonplace. City walls were built for protection and cities grew in size and number as more people sought refuge behind their walls. This development transformed the dominant political system of the third millennium. No longer were “temporary emergency leaders” adequate. Permanence was needed in the wake of permanent emergency.

War and victory were the overriding subjects of contemporary thought and became important topics in art. Epic tales celebrated the new rulers, giving man (as represented by the ruler) a prominence to rival the gods.

Conversely, the new idea of “ruler,” drawn from the then current political situation, was used to suggest the divine aspects of “majesty” and “energy.” The metaphor of god as ruler appropriately expressed the power of the gods, and of the earthly setting in which mankind experienced this power. In the third millennium, important gods became understood as manorial lords of their temple estates. Like their earthly counterparts, such estates were focal points of economic activity; they had large staffs of lesser gods as well as human workers. Like earthly rulers, the divine lords provided protection against external enemies and administered justice within their realms.

This new “ruler” metaphor also provided a new perspective on the universe. The whole cosmos became understood in terms of political organization. Each god had a role to play in this political entity, a role granted by the 022assembly of all the gods. In the fourth millennium, the gods’ immanence in natural phenomena had been perceived as an expression of their innate nature; in the third millennium, the gods assumed the roles and duties given them by the assembly of the gods, an essentially political body. This assembly of the gods was the highest authority in the universe. It met in Nippur and served as a court that passed sentence on wrongdoers, both human and divine. It elected and deposed kings (human and divine) and could condemn whole cities to destruction. These gods, now politically conceived, were active shapers of history.

The four most important gods in the third millennium were An, Enlil, Ninhursaga and Enki. Their powers corresponded to the four great cosmic elements: air, storms, rocky ground, and flowing fresh waters.

An was the power in the sky, the father of the gods, the procreator of vegetation. He was thus the image of paternal authority, who presided over the assembly of the gods and conferred earthly kingship.

Enlil was the god of the moist spring rains and of storms. Enlil was thus the embodiment of energy and force, the executive manager of the gods. Unfortunately, his power was not always beneficent. He could easily unleash fearful storms on man and thus destroy him.

Ninhursaga, the female of the supreme triad, was a many-faceted goddess. Originally, she was the power in the stony soil. She was also closely associated with wildlife and herd animals. She is preeminently the birth-giving mother (often under the name Nintur). Jacobsen suggests that the connection between birth and the “rocky ground” may be that the birth of herd animals normally occurred in the spring when the herds were pastured in the stony soil that rings Mesopotamia in the foothills of the Iranian ranges and in the Arabian desert. As birthgiver, Ninhursaga was the great midwife and the one who gave birth to kings. She did not, however, develop a political function in the organization of the gods and therefore progressively lost rank among the gods.

Enki, the rival third member of the divine triad, was the power in the sweet waters in rivers, marshes and rain. His was thus the power to fertilize and the power to cleanse. Because water moistens clay before it is shaped, Enki was also the god of artists and craftsmen, the most cunning of the gods.

Powers in the lesser cosmic elements were seen as the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of An.

In the second millennium, we see a critical change in religious orientation. For the first time, a concern for self 023predominates which gives rise to personal religion. Jacobsen is not clear what social and political changes account for this shift or what new fears provided the impetus. But that religion redirected itself to areas of personal concern is unquestionable.

And in Mesopotamian religion of the second millennium we find the clearest connections with Biblical religion. For example, compare Jacobsen’s definition of personal religion in second millennium Mesopotamia with Psalms 25 and 38. Jacobsen describes personal religion as the “religious attitude in which the religious individual sees himself as standing in close personal relationship to the divine, expecting help and guidance in his personal life and personal affairs, expecting divine anger and punishment if he sins, but also profoundly trusting to divine compassion, forgiveness and love for him if he repents.”

Now listen to the Psalms:

“Remember, Lord, thy tender care and thy love unfailing,

shown from ages past.

Do not remember the sins and offences of my youth,

but remember me in thy unfailing love.

The Lord is good and upright;

therefore he teaches sinners the way they should go.

…

Turn to me and show me thy favor,

for I am lonely and oppressed.

Relieve the sorrows of my heart

and bring me out of my distress.

Look at my misery and my trouble

and forgive my every sin.”

(Psalm 25)

And from Psalm 38:

“On thee, O Lord, I fix my hope;

thou wilt answer, O Lord my God.

I said, ‘Let them never rejoice over me

who exult when my foot slips.’

I am indeed prone to stumble,

and suffering is never far away.

I make no secret of my iniquity

and am anxious at the thought of my sin.

…

But, Lord, do not thou forsake me;

keep not far from me, my God.

Hasten to my help,

O Lord my salvation.”

The attitude reflected here is basic to both Judaism and Christianity. It finds its roots in second-millennium Mesopotamia.

Jacobsen is careful to note, however, that the typical humility and self-abasement of penitence presuppose a remarkable, almost arrogant feeling of human importance. We believe that we matter to God, that what we do is important to Him, that God cares about our deeds, our sins, and our repentance.

This second-millennium concept of God as intimately concerned with the daily affairs of the individual is a radically different religious perspective from the awe-struck perception of the mystery of natural phenomena which characterized fourth-millennium religion and the perception of the majesty of the organized universe which characterized third-millennium religion. In the second millennium, God is brought into the close personal world of the individual, who, for the moment, ignores the holiness and awesomeness of the Maker of the Universe.

But man cannot long ignore the non-personal aspect of God. Psalm 8 is a classic statement:

“When I look up at thy heavens, the work of thy fingers,

The moon and the stars set in their place by thee,

What is man that thou shouldst remember him, mortal man that thou shouldst care for him?

The coexistence of these two aspects of God is a basic paradox: The worshipper is overwhelmed by God’s majesty and holiness, and yet at the same time he approaches God on a very personal level, appealing to God for his personal salvation.

The origins of these conflicting attitudes are to be found in Mesopotamia, where the concept of personal religion originated. For example, listen to this Mesopotamian prayer.

I have cried to thee, (I) thy suffering, wearied distressed servant.

See me, O my lady, accept my prayers!

Faithfully look upon me and hear my supplication!

Say “A pity!” about me, and let thy mood be eased.

“A pity!” about my wretched body

that is full of disorders and troubles,

“A pity!” about my sore heart

that is full of tears and sobbings.

Texts reflecting this attitude toward personal religion appear early in Mesopotamia, toward the beginning of the second millennium, and there are no examples elsewhere in the Near East until half a millennium later. It seems clear that the concept of personal religion spread from Mesopotamia to Israel and Egypt, although we do not know how this occurred or the paths it took.

In Mesopotamia, however, the concept of a personal god was not perceived as contradictory to the idea of divine 024holiness and majesty because God’s personal aspect was reflected in personal gods rather than cosmic gods. In Mesopotamia an individual worshipped his personal god or goddess, as well as the great national gods with their cosmic offices; an individual’s personal god was in many ways a personification of the power for personal success in that individual. When one attained luck and good fortune, one “acquired a god.” The god inspired the individual to act and generally lent success to his plans. The personal god was the divine parent of the individual who cared for him as a mother and a father: he provided for his children, protected them, and interceded on their behalf with the higher powers. The god dwelt within the man’s body, was present even at the act of conception, and thus in a way engendered his children, who accordingly held the same personal god throughout the generations. Man dwelt in the “[protective] shadow of his god.” If the god got angry at the individual, however, he would leave, and with him went the individual’s power to succeed. Man therefore placated his personal god and induced him to return by penitence and penitential prayers. The humility of penitence—and the assurance of the god’s concern—is logical in the context of a “personal god.”

In Mesopotamian religion, this idea of the personal god as “parent” served as a psychological bridge to the many gods’ awesome powers. But even the great cosmic powers could be personal gods—although only of great men and royalty. These great cosmic gods too had loving concern for their children. All gods could thus be viewed as concerned and approachable, as the “parents” of man. A familiar filial attitude toward all the gods began to permeate religion, resulting in the general attitude called “personal religion.”

Another paradox familiar to the student of the Bible, which can also be found in Mesopotamian religion of the second millennium, is the paradox of the righteous sufferer; he finds himself in trouble despite his blamelessness. This problem is dealt with in two notable Babylonian works, the so-called Babylonian Job (“I will Praise the Lord of Wisdom”) and the Babylonian Theodicy. Neither of these compositions can provide the answer to a problem that is essentially unresolvable. As Jacobsen points out, however, in the Babylonian Job, for the first time the personal egocentric view of the righteous sufferer is rejected. The Babylonian Job is overwhelmed; he realizes how great the distance is between God in his cosmic majesty and individual man in his littleness; in this context, man cannot demand justice. This realization does not, however, result in the rejection of personal religion. With the help of the concepts of personal religion, man has become the son of God and can confront him on an intimate level.

A number of major Mesopotamian religious works developing the concept of personal religion were produced in the second millennium: the Atrahasis story, Enuma Elish, and the Gilgamesh Epic. According to Jacobsen, all are existential critiques of the universe; that is, each of them deals in a sophisticated way with basic questions of existence and the nature of the universe.

The Atrahasis story focuses on the destructive capacity of the power of the gods. Atrahasis’ response to this power is that man should increase his devotion to the gods and take care not to disturb them.

Enuma Elish is an attempt to understand the universe. It does this by telling us how Marduk became king of the gods. The story begins with the birth of successive generations of gods. One of the older gods, Apsu (god of sweet water, the progenitor god), rebels against the exuberant energy of the younger gods (which is their essence), but is defeated by Ea/Enki. Tiamat (god of the salt waters and also a progenitor) is then roused by an assembly of her children and she too rebels. The general assembly of the gods meets and confers kingship on Marduk (the state god of Babylonia). Marduk defeats Tiamat and then, by creating the universe, converts his temporary “kingship” into a permanent monarchy. Enuma Elish operates on many levels: It 025reflects the rise of Babylon as ruler over a united Babylonia; it is an account of how the universe is ruled; and it explains how monarchy evolved. According to Enuma Elish, the universe is grounded in divine power and divine will; both nature and society are characterized by political order.

The third great Mesopotamian religious work is the Gilgamesh Epic, a magnificent humanistic tale based on legends concerning a supposedly “historical Gilgamesh” (a ruler of Uruk circa 2600 B.C.). The subject of the story is man’s relationship to death. The story contains two sets of legends: One recounts the valor of the historical Gilgamesh; the other involves magical tales, such as “The Death of Gilgamesh” and “Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld,” both dealing with death.

As Jacobsen points out, almost diametrically opposed attitudes toward death are reflected in these stories. In some, Gilgamesh seeks to avoid death. In the magical tales, however, Gilgamesh almost recklessly courts death, but death nevertheless remains the great unavoidable evil. These antithetical attitudes are the theme of the epic, reflecting the development from an early disdain of death to an obsessive fear of it. When the story opens, Gilgamesh shares a heroic attitude of his time: he aspires to immortality through immortal fame. When death takes his friend Enkidu, however, Gilgamesh begins to comprehend the reality of death and realizes that he himself must die. His previous value system collapses; immortal fame now means nothing to him. He becomes obsessed instead with the quest for real immortality.

Ultimately, his ancestor Utnapishtim—who is immortal—tells him the story of the flood to demonstrate that Utnapishtim’s own achievement of immortality was unique and is not available to Gilgamesh. Utnapishtim then offers Gilgamesh a parting gift, the rejuvenating plant. But the plant is stolen from him by a serpent when Gilgamesh carelessly leaves it on the bank of a pool. According to Jacobsen, Gilgamesh’s very lack of heroic stature brings him to his senses. He cannot defy human nature, he must accept reality; only the relative immortality of lasting achievement can be his.

For Jacobsen, the second millennium was the high point of Mesopotamian religious achievement. He devotes only a short epilogue to the first millennium; these were disturbed times. Mesopotamia was invaded both by Arameans and the Sutu. Faced with the possibility of sudden death, Mesopotamian society reflected an increased interest in the powers of death and in the netherworld, and stories about them became increasingly popular. The religious outlook reflected the turmoil and increasing brutalization of the times. The gods of political enemies themselves became enemies, and were treated as such in rituals, in which these gods were maimed and killed.

But even in the first millennium the three major metaphors that Jacobsen discerns in Mesopotamian thought survived—god as provider (fourth millennium), god as ruler (third millennium), and god as parent (second millennium). God as provider was an official in charge of the beneficent phenomena of nature. The ruler metaphor justified the trend toward absolutism in earthly kingship. The parent metaphor continued to flourish not only in the penitential psalms and in rites of contrition, but in the idea of quietistic piety as well. Thus the torch of Mesopotamian religion was passed on.

What, if anything, can we learn about Biblical religion from the vast quantities of material relating to Mesopotamian religion? The answer is: a great deal. No single volume provides better evidence for this conclusion than the recently published and widely acclaimed book by Thorkild Jacobsen, The Treasures of Darkness—A History of Mesopotamian Religion.a Jacobsen is the revered master-scholar of ancient Sumer and Assyria. At 75, he has had an enormously fruitful and prolific scholarly life. Treasures of Darkness is a moving distillation of Jacobsen’s sensitive understanding of Mesopotamian religion. But this book is not directed to a Biblical audience. […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username