026

How many thousands of Christians were massacred when the Persians conquered Jerusalem in 614 C.E. is unknown, but if surviving historical records are at all reliable, the number was huge. We now have the first archaeological evidence that may be related to this tragic chapter in Jerusalem’s history—a mass grave of Christians at the precise location where a surviving list places one of them.

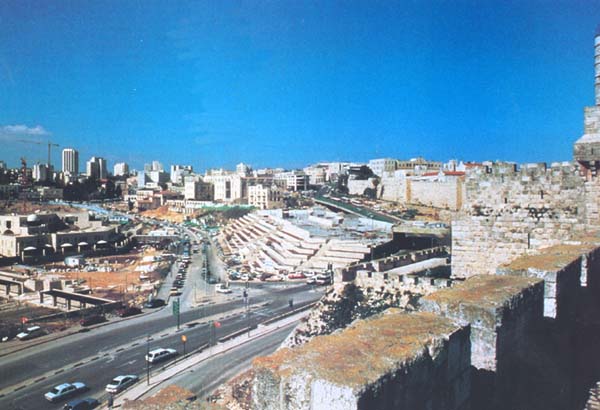

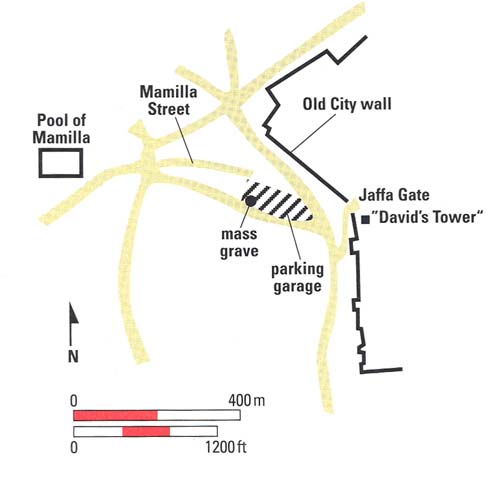

We often hear of urban expansion and development around the world resulting in the destruction of archaeological remains. In this case, however, development led to the discovery of archaeological remains. The area adjacent to Jerusalem’s Jaffa Gate, outside the western wall of the Old City, is known as Mamilla. Between 1948 and 1967 much of it was a no-man’s-land, between Israeli western Jerusalem and the Jordanian-held Old City. When the Old City fell to Israel in the Six-Day War, Mamilla became available for development. This did not occur, however, until 1989, when the municipality began construction of what is known as the Mamilla Project. It includes a residential area (already built in part), a commercial area with a large parking garage (completed) and a Hilton hotel (under construction).

As required by Israeli law, development projects may be carried out only with the consent of the Israel Antiquities Authority and with direct and permanent archaeological inspection.

Ancient remains were encountered soon after workers removed immense amounts of modern rubbish and debris, which had accumulated especially when the site was a no-man’s-land. The construction was then 028stopped to enable us to mount a rescue dig. This excavation, directed by the author,1 was carried out between 1989 and 1993.

In the area planned for the parking garage, we found a large number of tombs dating to different periods. About 20 tombs date to the late Iron Age (seventh century B.C.E.), Babylonian period (early sixth century B.C.E.) and Persian period (late sixth and fifth century B.C.E.—not to be confused with the Persian conquest in 614 C.E.). Another group of tombs is from the Second Temple period (second century B.C.E.–70 C.E.). They are of two types. One type consists of a vertical shaft. From the bottom of the shaft, one to four burials are cut sideways. This type of shaft tomb, which actually has no burial chamber, was previously unknown in Jerusalem in Second Temple times. The pottery and other finds indicate that these shaft tombs are slightly earlier than the common Second Temple tombs with kokhim (burial niches in the cave wall), which usually date to the second half of the first century B.C.E. and onwards.

There are about 20 of a second type. They are small individual tombs dating to the first century B.C.E. and first century C.E., formed by small rock-cut troughs lined with stone and then covered with stone slabs.

From the Byzantine period (fourth-seventh century C.E.), we found about 15 simple inhumations, either in the ground or in a shallow crevice or in a simple cutting in the bedrock.

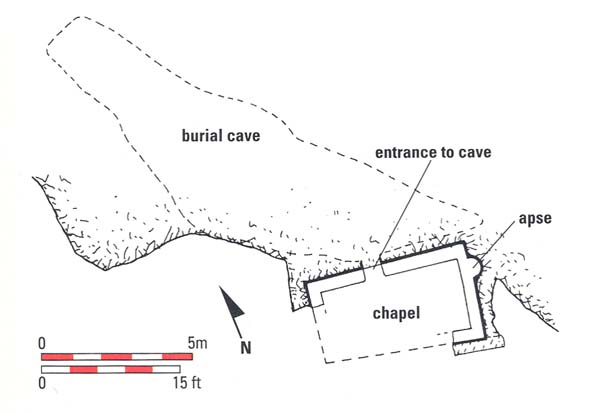

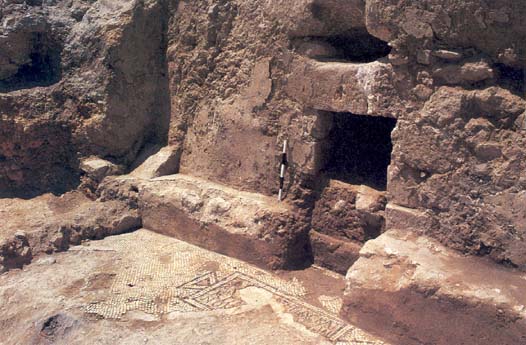

One especially outstanding tomb—Tomb No. 10—is the subject of this article. It was discovered by a bulldozer—or, more precisely, the bulldozer uncovered an opening in the face of a rock scarp that had been blocked with masonry.

When we dismantled the masonry, we were amazed to find behind it a large natural cave, nearly 40 feet long, filled with large piles of human bones arranged in no particular order, apparently thrown on top of one another helter-skelter.

Initially we had no clue as to the date of these burials. This would require careful excavation. But before we could do this, word of the discovery leaked out, and within a few days we were besieged at the site by the fanatically orthodox group that calls itself Atra Qadisha (Aramaic for Holy Site). The Atra 029Qadisha protesters pronounced the site an ancient Jewish tomb, which should not be touched.

At that time no one had any idea as to the identity of the people buried in the cave. But the Atra Qadisha people seemed to know with certainty. Ironically, the people in the cave turned out to be Christians. But the site soon became a battlefield. It had all the requisites that the ultra-Orthodox could desire: a site in the center of Jerusalem with convenient access and involving a major construction project with which they could interfere. They soon managed to block the breach in the cave with concrete. They also posted warning signs in their neighborhood of Me’a She’arim.

With the tomb itself blocked, we proceeded to excavate the area in front of the entrance, which revealed a small chapel of the late Byzantine period (c. sixth-seventh century C.E.). Two sides of the chapel (northern and eastern) were cut into the rock; the other two walls were of masonry. The chapel was over 16 feet long and about 10 feet wide (although the width varied somewhat). Much of the walls had eroded in antiquity; it was difficult even to locate the entrance. A small apse had been cut into the eastern rock-cut wall. A marble slab (of which only the stump survived) provided a simple altar in the apse.

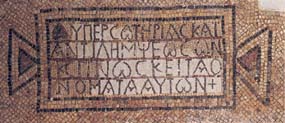

In the first of its two phases, the chapel was paved with a mosaic floor made of relatively rough white tesserae. Three simple crosses appeared just in front of the apse. In front of the blocked entrance to the tomb was part of a four-line Greek inscription set within a tabula ansata (a rectangular frame with a triangular “ear” on either side pointing to the frame). The text was of a formula well known from contemporaneous inscriptions, so it could be easily 030reconstructed: “For the redemption and salvation of those, God knows their names.”

The inscription was no doubt a reference to those buried in the mass grave we would eventually explore, a tribute not unlike that many countries have at the tomb of an unknown soldier.

Several layers of white plaster covered the chapel walls. The outer layer was divided into rectangular panels filled with straight lines and wavy patterns in imitation of marble slabs. The wall of the apse bore traces of a fresco of an angel extending his hands. Details of the head and halo are quite clear, but the face itself did not survive. The angel wears a yellow robe. The folds in the robe are made with black overpaint, as is the angel’s wing. Unfortunately, the rest of the composition did not survive. Since the angel faces right with hands extended, the right side of the composition may have depicted the Virgin Mary, as part of an Annunciation scene.

In the chapel’s second phase, benches along all four walls, seating nearly 30 people, were built on the mosaic floor.

While we were clearing the chapel, heavy machinery about 150 feet higher on the slope was demolishing a house on Mamilla Street. One morning, with no warning, a huge stream of water, as if set free from a burst dam, washed down the slope, leaving behind a strip of mud and destruction. We later learned that a bulldozer had broken a filled cistern in the house. Until the 1930s, houses in Jerusalem used cisterns with rainwater for their water supply.

After recovering from the shock of the “flood,” we examined the damage. Much of the benches had been destroyed. To our surprise, however, the fill used to create the benches (which were then covered with plaster) contained a cache of oil lamps. About 30 of them were intact; many others were just sherds. All of them were familiar late Byzantine “slipper-shaped” lamps. On the nozzle of each was either a cross or a palm leaf motif. Some of the lamps had no traces of soot on the nozzle, indicating they were never used. They were apparently hidden away in the construction fill as votive objects.

By this time, it seemed very clear that this site was Christian rather than Jewish: an eastern-facing chapel with an apse, a Greek inscription and crosses in the mosaic floor, oil lamps with Christian motifs, and the angel fresco in the apse. In addition, we found a cross incised on the lintel of the cave entrance. But none of this fazed the leaders of Atra Qadisha. With no evidence whatsoever, they came up with their usual contention: The Christians had reused an ancient Jewish tomb.

Oddly enough, nearby, other members of our team were excavating Iron Age tombs from the seventh-sixth century B.C.E., which in many respects could be considered Jewish tombs. Yet this excavation proceeded for several months under the watchful eye of an Atra Qadisha “inspector.” Incomprehensibly, our effort to excavate a clearly Christian tomb was regarded as a casus belli.

After a lengthy delay occasioned by the protesters, we decided on an end run around them: a midnight entry into the burial cave through another rock-cut entrance in the side. Instead of excavating as we normally would, we decided to place the contents of the tomb in cardboard boxes and remove the boxes in a single operation so that the contents could be studied in friendlier territory. Admittedly, this was not the best methodological procedure. But since the corpses had not been placed in the cave in any systematic way but had simply been thrown there in no apparent order, the loss would be slight.

We worked inside the cave for the whole night and the following day—myself, my colleague Eli Shukron and a small group of loyal and competent Arab workmen—emerging from the cave only the following night. We proceeded in this way for several nights. Incidentally, this may have been the first time that portable phones were used within a burial cave.

The contents of the tomb filled hundreds of boxes, all prepared for removal from the cave at one time. Things did not end well, however. After several nights 031we were discovered. There was a short fistfight before the protesters appeared to leave. Then we found that the tires on our cars had been slashed (the Antiquities Authority generously reimbursed us).

Worse than the damage to body and property, however, the protesters were able to enter the cave after we departed. Once inside, they cut open the boxes, turned them over and threw the bones all over. Perhaps this was their way of admitting to themselves what they would not state publicly—that they were making their stand in the wrong place, they were protesting the excavation of a Christian burial.

We were of course a licensed excavation, and the protesters were acting unlawfully, but the authorities wanted to bring a peaceful resolution to the matter. In the end we had to proceed with strict police protection. With the entire area barricaded to prevent protesters from entering, we opened the main blocked entrance of the cave and removed the bones, partly in intact cardboard boxes, partly in cut boxes and the rest loose. A single truck was sufficient. We then measured the plan of the empty cave, finally giving the site to the contractors. The empty cave has now been cut away and destroyed.

But our work had just begun. The anthropologists on our team, Yossi Nagar and Jaques Verdene, came up with some interesting findings. For example, the bones, in general, point to a relatively young population, younger than the normal age distribution we expect to find in a cemetery. This suggests a population slain in battle or a similar catastrophe. What was the explanation?

The discovery of several cross-shaped pendants when we sifted the dirt from the bones confirmed that these were Christians who were buried here.

Almost 130 coins, also found by sifting, were studied by Donald Ariel, the numismatic curator of the Israel Antiquities Authority. These enabled us to pin down the date of the burials. The date of the latest coin is of course the most important. The bodies could not have been placed here before the date of the latest coin. The latest coin was a gold coin minted by the emperor Phocas (602–610 C.E.). This is clear evidence that the burials are to be associated with the events of 614 C.E., when the Persians captured Jerusalem.

At this point we must look at the historical materials preserved in ancient texts. To understand one small incident on the large canvas of the time, it must be set in the context of the long confrontation between the two superpowers of the sixth and early seventh centuries C.E.—the Byzantine empire and the Persian empire—a confrontation that had its roots centuries earlier, in the days when it was Rome versus Parthia. The countries in between, such as Palestine, were, as usual, battlegrounds.

In the late sixth-early seventh century C.E., neither Persia nor Byzantium was monolithic; each had its own internal conflicts, which often exacerbated the conflict between the two empires. In 590 C.E. the newly enthroned Persian king Khosrau II was forced to flee for his life and take refuge with his enemy, the Byzantine emperor Mauricius (582–602 C.E.), who granted him asylum. Mauricius himself was soon slain by an army officer named Phocas, who subsequently became emperor. By this time, Khosrau II had returned to Persia, where he successfully reclaimed his throne. Khosrau then attacked Phocas, supposedly to revenge the killing of Phocas’s predecessor Mauricius, who had helped Khosrau when he had been in need. Ostensibly Khosrau sought to remove Phocas and place on the thrown the slain Mauricius’s son Theodosius, who could be regarded as the legitimate heir to the Byzantine empire. Of course the real reason for the Persian attack was 032territory, especially the territory Khosrau had ceded to Mauricius as the price for his asylum when he fled Persia and sought refuge with Mauricius.

Khosrau’s attack on the Byzantine empire was two-pronged. One prong headed toward Constantinople, the Byzantine capital. A secondary army headed south, under the leadership of a Persian general nicknamed Shahr Baraz—the Wild Boar.

Various parts of the Byzantine empire were also religiously divided. The Christian population of Syria and Egypt were Monophysites, who rejected the doctrine of Orthodox Christianity, adopted at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 C.E., which held that Jesus was both wholly human and wholly divine. The Monophysites (literally one nature) held him to be wholly divine. When Phocas tried to enforce Christian Orthodoxy on the Monophysites, riots broke out in Antioch, Alexandria and Jerusalem.

In 610 C.E. Heraclius became the Byzantine emperor. The Wild Boar, seeking to take advantage of the internal Christian riots, soon captured Antioch (611 C.E.) and Damascus (613 C.E.). He then turned to Jerusalem. His principal target was not the city itself but church treasure. The Persians wanted to humiliate the Byzantine Christian empire.

Jerusalem was besieged in April 614 C.E. The precise order of events is not entirely clear. Initially, the city apparently yielded peacefully, but the people soon revolted, retaking control of the city and thus forcing the Persians to lay siege again. This siege of the city lasted 20 days and ended with a Persian victory in May 614 C.E. During the fighting, the Persians indiscriminately slew every Christian they captured. They also began destroying churches, especially the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Church of the Ascension on the Mt. of Olives and the Church of Holy Zion. Zacharias, the Christian patriarch of Jerusalem, was exiled to Persia along with the relic of the True Cross. Able-bodied men and professionals were also exiled.

The Christians who remained, according to a contemporaneous Armenian historian named Sebeus, were gathered together outside the city wall in the Pool of Mamilla, located about 700 meters west of 033Jaffa Gate. There they were probably sold to the highest bidder, as was the custom.

The Persians then withdrew, granting control of the city to the Jews. The Persian empire was not based on religious principles and was indeed inclined to religious tolerance. Moreover, the Jews, who had suffered under Christian rule, had sided with the Persians when they assaulted Jerusalem. According to some sources, the Christian captives at Mamilla Pool were bought by Jews and were then slain on the spot.

A short time later (three years, according to one estimate), Persian policy shifted—the Jews were expelled from Jerusalem, and the Christians were given permission to rebuild their churches.

One of our main sources for these events is an account by a monk named Strategius, who was stationed at the Monastery of Mar Saba in the Judean Desert.a According to Strategius, a Christian survivor named Thomas the Undertaker and his wife collected the slain bodies and buried them at various sites, which are listed. Strategius’s original account was probably written in Greek, but only three Greek fragments have survived. We do have, however, six different early copies translated into Georgian and Arabic.2 Not all localities are mentioned in all copies. J.T. Milik has tried to harmonize the copies.3 He lists 35 different locations. Some are well known, such as Zion Gate and the Nea Church. Others are known, but their exact location is either in dispute or the archaeological evidence is insufficient to judge between two possibilities. The description of other localities is of a general nature or simply unknown, such as the “Serapion” or the enigmatic “City of Gold.”

The list also gives the number of bodies buried at each locality. Again, there are considerable differences among the six copies. The totals, however, are all enormous, ranging from 37,585 to 65,262.

Mamilla, or the Pool of Mamilla, is listed in all six copies. The number of burials at the site varies in different copies from 4,518 to 24,518.

The cave we have excavated, with the remains of over several hundred bodies, is perhaps the first archaeological evidence for the killing of Christians in the Persian conquest of 614 C.E. Not long after the victims were buried in this cave, a small chapel was added in front of it. The Greek inscription in the mosaic floor is the best commemorative inscription that could be added for those of whom only “God knows their names.”

In 622 C.E. the Byzantine emperor Heraclius opened a new military offensive against Persia, which lasted six years. In 628 C.E. he attacked the Persian capital and rescued the True Cross. On March 21, 630 C.E., 060Heraclius triumphantly entered Jerusalem, restoring the relic of the cross to its original location. Today no one knows where it is.

How many thousands of Christians were massacred when the Persians conquered Jerusalem in 614 C.E. is unknown, but if surviving historical records are at all reliable, the number was huge. We now have the first archaeological evidence that may be related to this tragic chapter in Jerusalem’s history—a mass grave of Christians at the precise location where a surviving list places one of them. We often hear of urban expansion and development around the world resulting in the destruction of archaeological remains. In this case, however, development led to the discovery of archaeological remains. The area adjacent to Jerusalem’s […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Yizhar Hirschfeld, “Spirituality in the Desert: Judean Wilderness Monasteries,” BAR 21:05.

Endnotes

I was assisted by archaeologists Eli Shukrun and Ya’akov Bilig. The excavation of the project was financed by the Karta Company. Assistance was also given by Gideon Avni, Jerusalem District Archaeologist, Israel Antiquities Authority. The entire project was carried out by the IAA. Preliminary reports on the discoveries have been published in Ronny Reich, Eli Shukrun and Ya’akov Bilig, “Jerusalem, Mamilla Area,” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 10 (1991), pp. 24–25, plate B at frontispiece; see also Reich, “The Ancient Burial Ground in the Mamilla Neighborhood, Jerusalem,” in Hillel Geva, ed., Ancient Jerusalem Revealed (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1994), pp. 111-118.

On the Georgian version, see G. Garitte, La Prise de Jerusalem par les Perses en 614 (CSCO 202–203, Scriptores Iberici 11–12; Louvain, 1960). On the Arabic versions, see Garitte, Expugnationis Hierosolymae A.D. 614, Recensiones Arabicae, I, A et B (CSCO 340–341, Scriptores Arabici 26–27; Louvain, 1973); II, C et V (CSCO 347–348, Scriptores Arabici 28–29; Louvain, 1974).