Going to the Bathroom at Lachish

056

In ancient Judah, the city of Lachish was second in importance only to Jerusalem. Lachish controlled the road that passed from the Mediterranean coastal plain through the Hebron hills to Jerusalem. This was probably the source of the site’s importance as evinced by the continuity of settlement in the site from the 10th century B.C.E. until 586 B.C.E., when it was destroyed by the Babylonians.

Excavations in 2016 at the ancient city gate were initiated by the Israel Antiquities Authority to facilitate visits to the site, which today is the Tel Lachish National Park.

Archaeological research has been carried out at Tel Lachish over the past 80 years by several expeditions. Two expeditions excavated parts of the entranceway and city gate, located on the southwestern side of the tell. The first archaeological expedition to the site was by a British team led by James Leslie Starkey in the 1930s. Their campaign ended with Starkey’s murder in 1938.

057

During the 1970s and 1980s, an expedition from Tel Aviv University led by David Ussishkin excavated inside 058the northern side of the main entrance, where they revealed that the gatehouse contained six rooms. Ussishkin excavated the three northern rooms of the gate, attributing the gate in Strata IV–III to the ninth–eighth centuries B.C.E. He then decided to leave the southern side of the gate for future generations to explore. Now, nearly 40 years later, we have completed the excavation of the southern half of the gate. This gate is one of the largest and most impressive gates ever excavated in Israel.

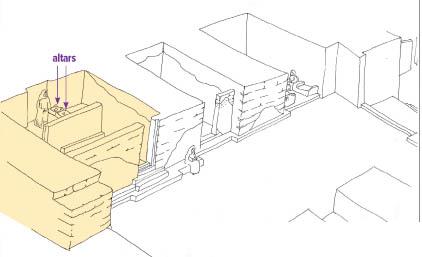

Its size corresponds to the importance of Lachish in the eighth century B.C.E. The gate has three chambers situated symmetrically on either side of the main street, with the main street crossing into the heart of the city. It is preserved to a height of about 16 feet.

A massive destruction layer evidenced by collapses of burnt mudbricks, ash, soot, broken pottery 059 and dozens of arrowheads was found at the gate. The layer testifies to the conquest of the city by Sennacherib, the king of Assyria in 701 B.C.E., an event that is known both from the Hebrew Bible and from a vivid relief found in Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh.

Discovered in one of the gate chambers was a gate-shrine where we believe the Israelite god Yahweh was worshiped. It was accessed by way 060 of four steps made from finely hewn stones. Plastered benches were located on either side of the steps. This chamber was divided into two rooms. The entrance into the smaller of the two rooms was intentionally blocked off before the destruction of the city gate in 701 B.C.E. by the Assyrians. The eastern side of this small room was paved with flat stones, while the western side was plastered.

Opposite the niche and next to the partition wall in the chamber, two horned altars, placed side by side, were revealed. The altars were constructed of hewn stones and plastered. Each altar had four horns. Seven of the horns had been intentionally cut off with a sharp object, while another one was preserved. It is possible to see the outline of the horns in the corners of the stones.

The small room was found to contain at least 90 pottery vessels. The assemblage included bowls, lamps and stands as well as jugs, juglets and kraters.

In the southwest corner of this small room, we exposed a 31-inch-wide pit that cut through the floor. Inside we discovered a large, squared stone lying on its side. The stone was well-carved and fashioned into a seat. It is 20 by 20 inches in size, and in the middle is a hole connected to the front with a channel. We have identified this to be a stone toilet, examples of which are known in Iron Age contexts in other parts of Israel and Jordan.

The assemblage discovered in the small room points to its use as an Israelite gate-shrine that was desecrated and transformed into a latrine. The gate-shrine has two clear phases.

During the first phase, a gate-shrine existed that was accessed by the stone steps that led into the large plastered room. This room contained a low bench used for offerings. In the smaller room, two stone altars with horns were placed opposite a plastered niche.

In our opinion, this room served as the “Holy of Holies” (the dvir, the innermost room of the Tabernacle) of the gate-shrine. The large amount of pottery vessels of the same type and particularly the bowls and lamps are typically found in cultic compounds and were probably used for offerings.

In its second phase, the gate-shrine was desecrated, possibly during the religious reforms imposed by King Hezekiah after he became king, as described in 2 Kings 18:4: “He [Hezekiah] removed the high places, broke down the pillars, and cut down the sacred pole [Asherah]. He broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the people of Israel had made offerings to it; it was called Nehushtan.”

The horns of the altars were intentionally cut off and a toilet was placed on the west side of the room in order to make it ritually impure and to ensure that the place would no longer be used for cultic purposes. These efforts were, we believe, part of Hezekiah’s attempts to centralize worship at the Jerusalem Temple.

The practice of destroying a cultic center and transforming it into a latrine is known in the Hebrew Bible, where the shrine of Baal in Samaria was destroyed by King Jehu as described in 2 Kings 10:27: “Then they demolished the pillar of Baal, and destroyed the temple of Baal, and made it a latrine to this day.”

Following the desecration of the gate-shrine, the room was sealed and was no longer used—for ritual purposes or as a latrine. This conclusion is supported by the following two lines of evidence: First, the intentional blockage of the entrance into the Holy of Holies shows that the inhabitants of Lachish did not dare use the former shrine as a latrine. Second, the cutting off of the horns of the altars and the placement of the latrine strongly suggest that these were both symbolic acts that were part of the larger program of religious reforms initiated by King Hezekiah in the last third of the eighth century B.C.E.

The evidence from the Lachish shrine joins the well-known cases of the abolishment of the temple of Arad and the demolition of the altar at Beer-Sheva that are also attributed to Hezekiah’s cultic reform by their excavators.

The Iron Age gate at Lachish is one of the largest gates that has ever been excavated in the Land of Israel. And, this is the first time that a gate-shrine has been discovered in Israel during an archaeological excavation. The gate-shrine went out of use during the end of the eighth century B.C.E. and was made ritually impure.

An ancient stone toilet recently unearthed at Lachish may provide archaeological evidence of King Hezekiah’s religious reforms throughout Judah in the eighth century B.C.E. The toilet had been placed in what is interpreted to be a gate-shrine within the largest ancient city gate found in Israel.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username