016

017

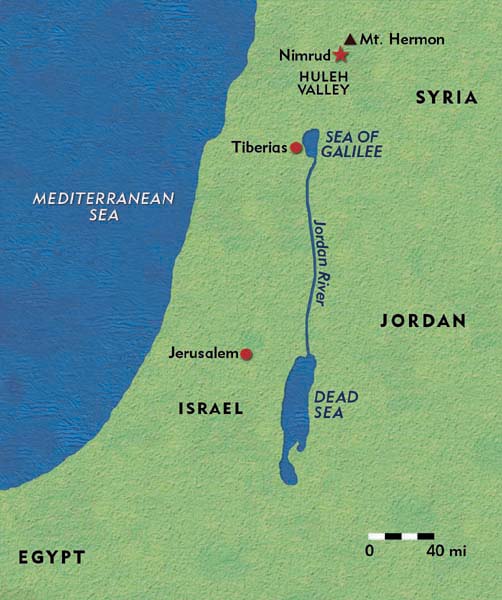

Nimrud is the largest and most perfectly preserved Crusader-period fortress in Palestine. It sits on the southern slopes of Mount Hermon, in present-day northern Israel, on a north-south ridge of a deep gorge. H.H. Kitchener (1850–1916)—a British engineer who conducted an archaeological survey in Palestine in the mid-1870s and later became the proconsul in Egypt—described it as “the finest ruined castle … in the country.”1 In 018medieval times it was known as Qalat al-Subayba, and scholars still refer to it as Subayba, but it is far better known as Qalat Nimrud.

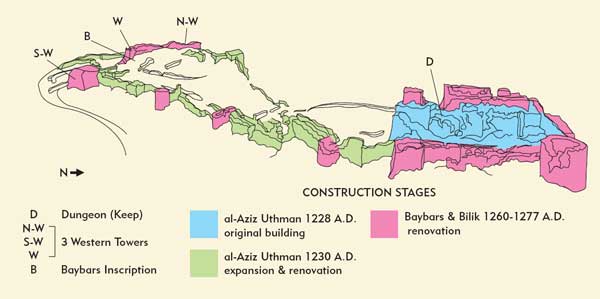

Until a few years ago, it was generally assumed that the Crusaders built this magnificent structure in the 12th century C.E. My recent analysis, however, indicates that Subayba/Nimrud was built by Arabs. Careful examination reveals that the structure was built in three phases. The initial structure (phase I) was substantially remodeled and extended (phase II) and subsequently destroyed. Then the fortress was rebuilt (phase III) on an even grander scale. But all three phases were the work of Muslims, not Christian Crusaders. Phases I and II were undertaken during the Muslim Ayyubid period in the first half of the 13th century C.E., whereas phase III was the work of a late-13th-century C.E. ruler of the Mamluk period.

The first hint that there is something wrong with the assumption that the Crusaders built Subayba/Nimrud comes from a reexamination of the historical sources. It has long been thought that the fortress was initially built between 1130 and 1165 C.E., when Frankish Crusaders ruled the town of Banias, which is only two miles from the site. The two sources that are cited in support of this dating, however, prove valueless. The first is a Muslim geographer and historian named Ibn Shaddad, who died in the late 13th century. He says only that an unnamed person mentioned to him that Subayba had been built by the Franks in the 12th century. He seems to indicate, however, that he tried to corroborate the information but was unable to do so.

The second source, a 13th-century Frankish jurist named Jean d’Ibelin, mentions a place called l’Assebebe (or, in several manuscripts, la Sebebe). But d’Ibelin calls l’Assebebe a town, like Banias, not a chateau (castle), which would have been more appropriate if he had meant the fortress. Moreover, the two lists compiled by d’Ibelin that mention l’Assebebe include a number of fortresses that did not exist in the 12th century. In one feudal district, d’Ibelin includes places that, in fact, were not in proximity to one another. Finally, his exclusive use of the Arabic name for a place ostensibly established by the Franks makes the reference all the more unreliable.

Again, both of these sources date to the second half of the 13th century. There is no source in the 12th century or the first quarter of the 13th century that mentions the name l’Assebebe or anything similar. Nor are there Latin or Arabic sources describing the construction of any castle in the area during this period. Since Subayba/Nimrud is bigger and more impressive than any other fort built in the areas controlled by the Crusaders in the 12th century, is it not surprising that it wasn’t even mentioned? Finally, if it had indeed been built by the Crusaders in the 12th century, one would expect that its location—near the border with Damascus—would have elicited some reaction from the Muslim rulers. We know of none.

There are several reports of events from 12th-century Palestine, but Subayba is never mentioned. For example, the Crusader historian and archbishop William of Tyre (c. 1130–1186) refers several times to events that occurred in Banias after its capture by the Crusaders in 1129, but he never mentions any castle in the vicinity. Indeed, in his study of the history of Banias from biblical times to his own day, William 019makes no mention of any fort built by the Crusaders on the adjacent mountain.

One other example: In 1184 the Spanish Muslim traveler Ibn Jubayr journeyed from Damascus to Acre. He described his journey in great detail and was at pains to name all the villages where he slept. On the third day after his departure from Damascus, he left the village of Bayt Jan for Banias, where he spent the night. In his description of Banias and its environs, he mentions that the town “is controlled by a fortress which the Franks call Hunin.” Hunin is the Crusader fortress Castellum Novum, which lies on the opposite side of the Jordan Valley! Is it possible that Ibn Jubayr, an observant and generally reliable traveler, simply did not notice the huge castle of Subayba that straddled his path? Hardly!

These and other 12th-century sources indicate that Subayba did not exist at that time but was built later.

Some scholars have tried to finesse these objections by suggesting that a 15th-century reference to “Subayba, also known as Banias” shows that references to Banias could be to Subayba. However, aside from the fact that this reference describes a situation in the 15th century, not the 12th, it says that Subayba was known as Banias, not that Banias was known as Subayba.

We reach the same conclusion if we ask what purpose the castle/fortress would have served had the Crusaders built it in the 12th century. It seems clear that it was too large to function merely as a means of defense for an insignificant town like 12th-century Banias, which the Muslim rulers of Damascus had not hesitated to cede twice to other powers: once to the Islamic Ismaili sect, and once to the Crusaders. As the great 19th-century American orientalist Edward Robinson observed long ago, Subayba, situated more than two miles from Banias, could not have been built for the protection of that city.

The Arab writer Sibt ibn al-Jawzi (who died in 1256) claims that the 13th-century sultan al-Aziz Uthman was the builder of Subayba. He is surely right. At the time, al-Aziz Uthman was the ruler of Banias.

That al-Aziz Uthman was the original builder of Subayba is also supported archaeologically. Eleven inscriptions have been discovered at the site, seven of them by the present writer. Six of the eleven inscriptions mention al-Aziz Uthman. The earliest one has long been known and might be the foundation inscription of the fort. It bears the date 625 after the Hegira, equivalent to 1227–1228, and expressly refers to the construction of the fortress (bashura), not to its renovation. This inscription was found on the first tower, which is attached to the wall of the fortress’s dungeon.

In the five other inscriptions that mention al-Aziz Uthman, Subayba is not called a bashura but a thaghr (specifically a border fort). These later inscriptions also describe the expansion of the castle.

The original building is difficult to distinguish from the renovation because they both used the same method of construction. The stones are imperfectly shaped, the vaults are very simple and there is almost no ornamentation—all signs of an economical method of construction. Until recently, the best ways to distinguish between the original construction and the 020renovation were to study the inscriptions and to examine aerial photographs taken before 1967. (After 1967 sheep- and goat-grazing were prohibited in the area; subsequently, the growth of dense foliage made aerial photos much less useful.) Based on this information, the two phases of construction can be distinguished as in the drawing. Positive identification, however, will be possible only by extensive archaeological investigation.

The inscriptions indicate that al-Aziz Uthman completed the renovation of the fortress in 1230. Its area was considerably increased and included the whole west side with its three towers. In each of these towers was an inscription commemorating the restoration work of al-Aziz Uthman. Two gates were also added on the southern end of the ridge.

Before considering Subayba’s third phase (when it 021was rebuilt on an even larger scale), we might look at how it functioned during its first two phases.

The story of Subayba’s origins begins with the great sultan Salah al-Din (Saladin), who unified the eastern and western (Egyptian) parts of the Abbasid caliphate, which was ruled from Baghdad, in the late 12th century. When Salah al-Din died in 1193, a prolonged struggle ensued between his sons, who sometimes broke into open warfare. It is highly unlikely that Subayba would have been built during these dynastic conflicts, however, because the warring brothers were careful to preserve the military status quo. The construction of so large a fort by one of the sons, or by one of their allies, would have led to a bitter military confrontation with the others. Moreover, in the numerous accounts of the political infighting, Subayba is not mentioned.

The quarrels came to an end only when Salah al-Din’s brother, al-Malik al-Adil, succeeded in becoming the paramount prince of the new Ayyubid confederation. In 1218, he handed over control of the Banias region to his son, al-Aziz Uthman. A year later Banias was plundered by Crusaders during the Fifth Crusade (1218–1221). In the upheaval, the Arabs themselves destroyed all the fortifications in western Palestine, as well as the fortress in the town of Banias. Subayba could only have been built once the tide turned, in 1221, and the Crusaders were thrown out of the area. So I believe the fortress was first constructed only after 1221.

The appanage left to al-Aziz Uthman, Banias, was a secondary one, however, so it is doubtful that the proceeds from the land were sufficient to finance a large building project like Subayba. Assistance would probably have been required from the court in Damascus. Why would al-Aziz Uthman have sought such assistance? And why did he not have the name of the Damascus sultan included in the inscriptions relating to the construction or the restoration?

In 1227 the Ayyubids became divided, with the northern forces in Damascus vying with the southern forces in Egypt for control of the confederation. The ruler of Egypt, searching for an ally to face the growing power of his Islamic rivals in the north, approached 023Emperor Frederick II and suggested that they form a German-Egyptian alliance with the aim of opposing the northern Ayyubid powers. In return for this assistance, the ruler of Egypt was prepared to give Jerusalem to the German ruler. On learning of these terms, the northern powers readied themselves for war against the Egyptian-German alliance. In October 1227 a German advance force arrived in Palestine. Though part of it left almost immediately after its arrival, feverish preparations began for what was seen as the approaching war. In fact, the threat of a mass crusade led by Emperor Frederick II (which never materialized) hung over the Levant for years.

This, in my opinion, was the reason for the construction of the original fortification at Subayba. As the fort had to be built in a great hurry, the method of construction employed was a most economical and speedy one.

The site was chosen to protect Damascus. It was perched above the principal trade route between the Huleh Valley (in modern Israel) and Damascus. The job of constructing the fort was entrusted to al-Aziz Uthman, as it was built in the area bequeathed to him. There is no doubt, however, that officials in Damascus helped with the necessary finances and manpower for completing the construction in the shortest possible time. In 1227, however, the sultan in Damascus, al-Mu’azam, died—before the construction of the Subayba fortress was completed. This probably accounts for the fact that he is not mentioned in the inscriptions.

Although the first phase of Subayba was built speedily, after things calmed down al-Aziz Uthman had time to complete and extend the fortress. Thus phase II.

The fortress that we see today, however, is Subayba’s third—and final—phase. In 1260 the fortress was destroyed by the Mongols, an empire that arose on the steppes of central Asia in the early 13th century and came to conquer China, Russia, much of eastern Europe and much of the Near East.

In 1260 the Mamluks, the Muslim successors to the Ayyubids, took control of the area. Under the Mamluk sultan Baybars (1260–1277), the walls of Subayba were 050restored and renovated. In the courtyard near an entrance tower is a monumental engraved inscription on five large stones (one of which is broken), dating to 1275 and bearing the name of Baybars, as well as the name of the vice-sultan Bilik, who had received the area and castle as private property and who actually initiated the building project described in the inscription.2

The work completed during Baybars’s reign was sophisticated and carefully executed. The new towers had domed roofs, for example. Most domes at the time were constructed with a series of circular layers decreasing in circumference. These domes, however, were constructed with square layers of stones and a central pillar supporting the roof.

I have not come across this system of building in any Crusader, Ayyubid or Mamluk fortress in the Levant.

So the Crusaders had no part whatever in the building of Subayba/Nimrud. It was first built by the Ayyubid rulers in Damascus via the efforts of the ruler of Banias, al-Aziz Uthman, in 1228. It was intended as part of a new defense line to Damascus on the western slopes of the Golan Heights, built to fend off a possible Crusader invasion by Frederick II. When this did not come to pass (he was indeed ceded Jerusalem and then quickly left the Holy Land, never to return), al-Aziz Uthman completed the fortification at his leisure. After suffering much damage during the Mongol invasion of the mid-13th century, Subayba was restored and enlarged under the Mamluk sultan Baybars, whose reign left us the magnificent structure that we see today.

For more photos of the stunning Nimrud fortress, visit our Web site at archaeologyodyssey.org.

Nimrud is the largest and most perfectly preserved Crusader-period fortress in Palestine. It sits on the southern slopes of Mount Hermon, in present-day northern Israel, on a north-south ridge of a deep gorge. H.H. Kitchener (1850–1916)—a British engineer who conducted an archaeological survey in Palestine in the mid-1870s and later became the proconsul in Egypt—described it as “the finest ruined castle … in the country.”1 In 018medieval times it was known as Qalat al-Subayba, and scholars still refer to it as Subayba, but it is far better known as Qalat Nimrud. Until a few years ago, it was […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

I am grateful to Reuven Amitai for this description of the third phase. See Reuven Amitai, “An Arabic Inscription at al-Subayba (Qal‘at Nimrod) from the Reign of Sultan Baybars,” in Moshe Hartal, The al-Subayba (Nimrod) Fortress, Towers 11 and 9, Israel Antiquities Authority Reports, no. 11 (Jerusalem, 2001), pp. 109–124.