Have the legendary gold mines of King Solomon been found? In the past year, the U.S. Geological Survey announced that they may have found King Solomon’s mines at Mahd adh Dhahab, an ancient mine in central Saudi Arabia between Mecca and Medina. The New York Times quoted Dr. Robert Luce, one of the geologists who was part of the American-Saudi team exploring the area, as saying, “Our investigations have now confirmed that the old mine could have been as rich as described in biblical accounts and, indeed, is a logical candidate to be the lost Ophir … ‘King Solomon’s Lost Mines’ are no longer lost.”

When BAR spoke to Dr. Luce, he was a bit more reluctant to commit himself. He stressed that he and the four other U.S. Geological Survey scientists who had been working in Saudi Arabia were geologists, not archaeologists, and that they did not have conclusive evidence that would date the mining at Mahd to King Solomon’s time.

To have been the fabled Ophir, the mine would have to satisfy two criteria: First, it must have been rich enough to have produced the almost incredible amounts of gold attributed to the mines at Ophir by the Bible. Second, the site must be located so that the gold could be easily transported back to Jerusalem, either by land or by sea. The Geological Survey geologists are fairly sure that Mahd (and possibly the area around it) could have satisfied both of these criteria.

Although the Bible contains numerous references to “the gold to Ophir,” (in Job, Psalms, Kings, Chronicles and Isaiah) none of these references pinpoints its location. Perhaps its location was so well known that no description was thought necessary or perhaps Ophir did not refer to a single specific location but to a mining region.

Before a large ancient mine had been discovered in the Middle East, scholars searched just about everywhere else for Ophir. The best guess around the turn of the century was Africa, where substantial gold mines had been found.

Then, in 1932, an American mining engineer named Karl Twitchell was sent to Arabia at the request of King Ibn Saud to explore the country’s mineral resources. He found the remains of a huge ancient mine covering several square miles. The Saudis named it Mahd adh Dhahab or “cradle of gold.” Twitchell found almost a million tons of ore tailings (refuse left over after the ore is treated) on the site. The tailings contained about 6/10 of an ounce of gold per ton; the mined ore, as opposed to the tailings, had obviously been far richer. Twitchell also found several deep stopes or trenches and hundreds of hammers, wedges and grindstones, indicating a variety of ancient mining methods. The simplest method was to remove the surface gold, either by picking up nuggets or crystals, or by panning or winnowing the gold from the surface dirt. More difficult was the process of digging trenches to get at the veins of gold ore and then cracking the rock with heat or using tools to dig out the ore. The gold was then separated from the ore with hammers and grindstones.

Twitchell established that there were at least two periods during which the ancient gold mine at Mahd was worked. The later period occurred between 750–1150 A.D. as indicated by datable pottery sherds and Kufic inscriptions found at the site. However, Twitchell could not date the earlier period. He conjectured that “from the general appearance of the ancient stopes in the mine mountain, as well as the tailings, it is not impossible that these date back to the time of King Solomon.”a

Twitchell advised the Saudi government that with modern mining methods the ancient mine could be expected to yield further riches. A British syndicate was set up which mined the site from 1934 to 1954. During this period $32 million worth of gold was produced, as well as substantial amounts of silver. Digging stopped only when the mine had penetrated 600 feet below the surface and was no longer considered profitable.

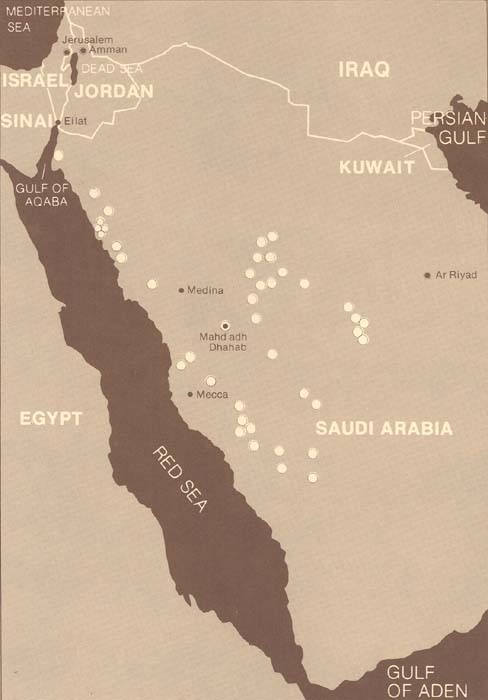

The British syndicate also found 55 other ancient mines in Saudi Arabia, but only at Mahd adh Dhahab was the lode considered rich enough and large enough to justify developing a modern mine.

The combined Saudi-U.S. Geological Survey team that started its work in 1972 was essentially called in to do what Twitchell had done—to survey the country for ore deposits. The modern geologists substantiated Twitchell’s findings. Dr. Luce of the U.S. Geological Survey emphasized that Twitchell is entitled to priority of discovery of the ancient gold mine at Mahd adh Dhahab. However, the modern geologists found even more gold ore deposits throughout the country (see map), and substantiated the truly enormous amounts of gold that the ancients extracted at Mahd.

Many scholars believe that Biblical “Ophir” was not one mine but many, although Mahd adh Dhahab may have been the largest. Twitchell mentions an Arab legend that King David’s miners worked at a site known as Umm Garayat. This mine is inland somewhat north and east of Mahd.

One Geological Survey scientist, Dr. Ralph Roberts, became intrigued with the ancient problem and wants very much to date the earlier levels of mining at Mahd adh Dhahab. He has returned to Saudi Arabia with the hope of finding datable sherds; he is also considering using modern scientific techniques such as radiocarbon and thermo-luminescence. He is researching and exploring ancient caravan routes for any clues they might provide.

Recently the mine area in which Mahd is located was leased by Consolidated Gold Fields Inc., a London based mining company. They will do further drilling and explore new parts of the mine area which contain still more gold, silver and other minerals. Perhaps they will be able to date some findings.

Although the Biblical accounts as to the amounts of gold produced at Ophir is probably exaggerated, there is no doubt that Biblical Ophir, wherever it was, produced huge quantities of gold during a relatively short period—in approximately 80 years between 1000 and 920 B.C., during the reigns of David and Solomon. This was one of the few periods when the Israelites had a united country and control of the necessary trade routes.

The Bible tells us that King David contributed 3000 talents of gold from Ophir to the building of the Temple (1 Chronicles 29:4). One talent equals about 1224 troy ounces and would be worth about $170,000 on today’s market ($140 per ounce). 3000 talents would be worth about $500 million.b

In 1 Kings 9:26–28 we are told that Solomon built a fleet of ships which, under the command of King Hiram of Tyre, left the port of Ezion-geber on a journey to Ophir and brought back 420 talents of gold. (This journey is reported again in 2 Chronicles 8:17–18, where the amount is reported as 450 talents).

According to the Bible, Solomon had extraordinary amounts of gold available to him. Besides Hiram’s fleet, Solomon had another fleet at his disposal, the ships of Tarshish, which brought him gold every three years. The altar, the inner sanctuary and even the floors of Solomon’s Temple were overlaid with gold (1 Kings 6:20–36). The tables, lamp stands and all the sacred vessels in the Temple were made of pure gold (1 Kings 7:48–50). Gold was so plentiful for King Solomon that he overlaid his throne with it, had 500 shields made of pure gold, and even used gold for his drinking cups! (1 Kings 10:16–21). 1 Kings 10:14–16 states that the weight of gold that came to Solomon in one year was 666 talents, not including gold which was offered him by traders and other rulers (such as the Queen of Sheba who brought him 120 talents as a gift).

Even allowing for considerable exaggeration, Mahd adh Dhahab seems to have been the only mine in the Middle East that might have had a gold-producing capacity which would justify these descriptions of Solomon’s gold. According to Twitchell, the surface ore mined by the ancients was doubtless richer than the deposits further down. If one adds the output of smaller mines in the area, the region becomes a prime candidate for identification as Ophir.

But could all of this gold have been transported back to Jerusalem, either by land or sea? Dr. Roberts, who is still researching possible land routes, agrees with other scholars that Mahd adh Dhahab was near at least one major north-south caravan trail. The distance overland to Jerusalem is about 700 miles, not impossible even in those days. Other smaller mines, such as Umm Garayat, are closer and a caravan might have picked up their output along the way to Jerusalem.

Sea routes, which are mentioned in the Bible as having transported gold, were relatively easy. The ancients would have had to bring the gold out from Mahd adh Dhahab to a port on the Red Sea (about 150 miles) and then ship it up through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba to Ezion-geber (about 500 miles). A British navy man named Charles Craufurd, who saw duty in the Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf and Red Sea during the early 20th century and returned to the region to live and travel after his retirement, speculated that Hiram’s ships were probably small coastal vessels similar to the fishing boats still being used in the Red Sea in the 1920’s. These ships could easily have made the trip from the mine area to Ezion-geber in a month or two. Craufurd believed that the ships of Tarshish were seagoing vessels, capable of ocean voyages.c Tarshish seems to have been Spain, Sardinia or some place in the Mediterranean area, inhabited at the time by Phoenicians, famous for their seamanship.

The difference between the two fleets could explain two Biblical quotations that have often puzzled scholars in the past: “Once every three years the fleet of ships of Tarshish used to come, bringing gold, silver, ivory, apes and peacocks” (1 Kings 10:22 and 2 Chronicles 9:21) and “Moreover the fleet of Hiram, which brought gold from Ophir, brought from Ophir a very great amount of almug wood and precious stones” (1 Kings 10:11 and 2 Chronicles 9:10). Scholars reasoned that many of these items did not exist in the Middle East and therefore Ophir had to be outside the Middle East—perhaps Africa. But it is possible that the ships of Tarshish could have put in at the same coastal port as Hiram’s ships (either the port serving Mahd adh Dhahab or a port further south on the Arabian Coast) on their way back from trading cruises to India, Africa and the Far East. These ships could have supplied Solomon with peacocks, apes and spices from far-off places. Perhaps these large ships transferred some of their cargoes onto smaller ships for the trip up to Ezion-geber. This would explain how Hiram’s ships were able to bring back exotic woods and precious stones if these items did not exist on the Arabian peninsula. The term “Ophir” might have referred to the whole region around the mines, including the coastal port. No one has yet found evidence of an ancient port that might have served Mahd adh Dhahab, but then again, until the 1930’s no one had discovered a large ancient gold mine either!

MLA Citation

Footnotes

One talent equals 3000 shekels (see Exodus 38:25–26) and one common shekel equals .408 ounces. See R. B. Y. Scott, “Weights and Measures of the Bible,” The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 22, pp. 22–40 (1959).