How Biblical Hebrew Changed

People often think of the Hebrew Bible as having been written in a single language called Biblical Hebrew and this language being the same from beginning to end. In fact, the Hebrew language went through three different phases during the Biblical period, and these three phases are reflected in different passages and books. In short, Biblical Hebrew is far from being homogeneous.

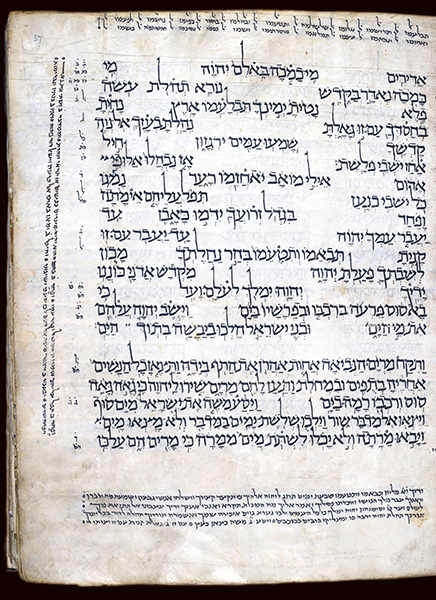

Despite its seemingly uniform façade—beginning with Genesis and ending with Chronicles—beneath the surface, various strata reflect considerable diversity. A linguistic analysis of this data often allows us to mark chronological milestones in the history and development of Biblical Hebrew as crystallized and preserved in the so-called Masoretic text, the standard Hebrew Bible in use today.a The great Semitists and Hebraists of the 19th century already dealt with this matter, and modern linguistic scholarship confirms their basic chronological conclusions.

Biblical Hebrew may be divided into three principal historical strata: (1) Archaic Biblical Hebrew, (2) Standard (or Classical) Biblical Hebrew and (3) Late (or post-Classical) Biblical Hebrew. This division, on the whole, is widely accepted among linguists and philologists of Biblical Hebrew, although it is somewhat arbitrary because developments in languages do not occur overnight, and transitions from one phase to another are mostly gradual.

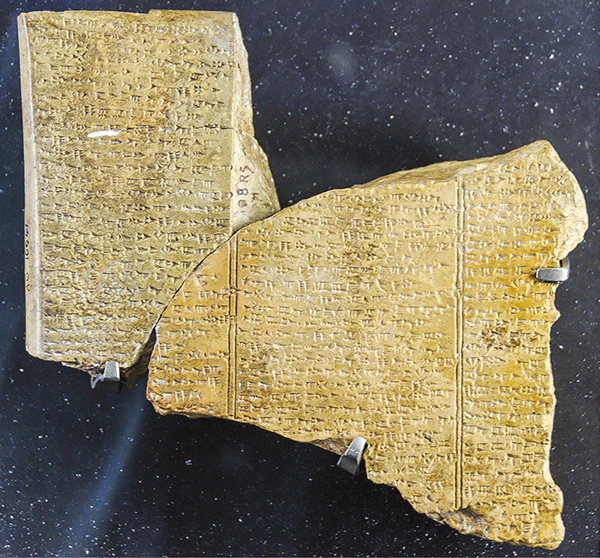

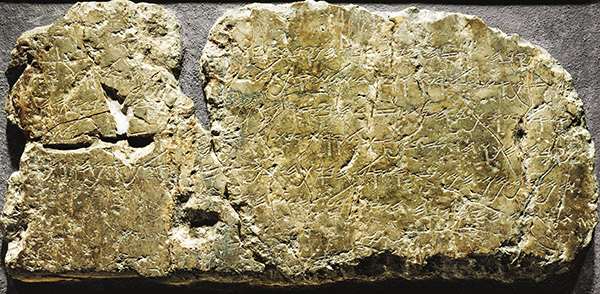

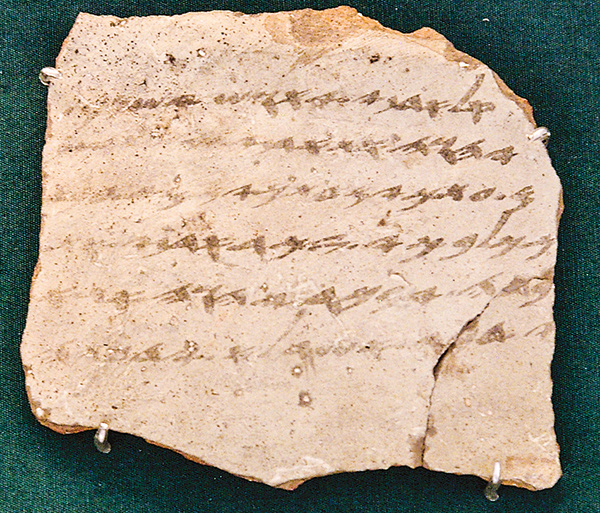

The limited scope of the Hebrew Bible—in size, content and subject matter—significantly restricts our ability to describe exhaustively the various linguistic strata it preserves. It is therefore of great importance to examine extra-Biblical sources that can expand and complete what we know in places where the Biblical picture is sketchy. Thus, for instance, texts from Ugarit in Syria, dating to the mid-second millennium B.C.E., make a significant contribution to our understanding of the background and nature of the language of archaic Biblical poetry. Similarly, inscriptions preserved from the first half of the first millennium B.C.E. provide us with invaluable information regarding the study of Biblical prose from the Standard or Classical stratum. And, finally, documents and texts in Aramaic and Hebrew from the Dead Sea Scrolls and rabbinic literature, dating from the second half of the first century B.C.E. until the first centuries C.E., enable us to identify the linguistic features of the Bible’s post-Classical stratum.b

1. Archaic Biblical Hebrew is documented in the Bible, particularly in the poetic parts of the Pentateuch and in the Early Prophets (e.g., the well-known Song of the Sea [Exodus 15] and Song of Deborah [Judges 5]), as well as in hymns from the Book of Psalms.c

2. Standard (or Classical) Biblical Hebrew is found in the prose sections of the Pentateuch and the Early Prophets like Isaiah and Jeremiah and in the Classical prophecies of the Later Prophets like Hosea, Amos and Micah.

3. Late (or post-Classical) Biblical Hebrew is found primarily in the late compositions included in the third section of the Hebrew Bible known as the Writings—in such books as Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah and Chronicles.

Scholarly opinion is sharply divided regarding the age of the first category. But linguists and philologists do agree that the Classical and Late strata of Biblical Hebrew may indeed be assigned to the First and Second Temple periods, respectively. This periodization is corroborated by the fact that the sixth century B.C.E. marks a significant turning point in Biblical literature’s linguistic history occasioned by the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem and the First Temple in 586 B.C.E. Compositions written from this time forward exhibit distinctive linguistic features not found in texts written in Standard Biblical Hebrew.1 Furthermore, many of these linguistic innovations also appear in extra-Biblical sources that date to the post-Classical period. The correlation between the two sets of data—in the Bible and in extra-Biblical literature—substantiates the conclusion that the linguistic background of the later period is reflected in these sources.

This last linguistic development is undoubtedly a direct outcome of both the exile to Babylon and the return to the Land of Israel. On the one hand, the deportation to Babylon of the Jewish people—who included the intellectual stratum of Jewish society that perpetuated its culture and literature—caused the physical detachment of the exiles from their national linguistic milieu. On the other hand, these exiles lived in Babylon for about 70 years (i.e., some two to three generations) among a foreign population whose written and spoken language was Aramaic. Furthermore, during the Restoration period (when the exiles were permitted to return), Aramaic reached the height of its influence and distribution, serving as the lingua franca, or common tongue, of the entire ancient Near East and the language of correspondence of the succeeding Persian kingdom’s administration. The boundaries of Imperial Aramaic stretched “from India to Ethiopia/Nubia” (Esther 1:1) and of course included the Land of Israel. It is thus not surprising that many linguistic innovations attested for the first time in Restoration-period literature are the direct or indirect result of Aramaic influence, which is evident in all realms of the language—its vocabulary, grammar and syntax.

Determining whether a linguistic feature deviates from Standard Biblical Hebrew and belongs to Late (post-Classical) Hebrew may be illustrated by the following example: The word iggeret (

In the very late book of Esther (9:29), we read that Queen Esther “wrote a second letter (iggeret)” to the king. Similarly, in 1 Kings 21:11 we read that Naboth’s townspeople did as Queen Jezebel had instructed them “in the letters she had sent them.” However, the word used here is not iggeret (

Sepher is also used in this context in First Temple-period epigraphic sources—for example, in the letters excavated at Lachish and in texts from Ugarit. Furthermore, when the word sepher, meaning “letter,” is translated in post-Classical times (in the Aramaic Targums and the Syriac Peshiṭta), the word used in the translations is iggarta (

The use of iggeret is just one of many instances attesting to the fact that Biblical Hebrew was far from monolithic. The scope of its “archaisms,” on the one hand, and its post-Classical “neologisms,” on the other, prove unequivocally that the language was not frozen during its thousand-year history, but was subject to an ongoing process of modification. The small group of so-called “minimalists” claims that Biblical literature “was written more or less at one go, or at least over a relatively short period of time, so that the texts quite naturally do not reveal signs of significant historical differentiation.”2 However, this view is conclusively refuted by the evidence reviewed here and described at greater length in scholarly literature.3 As demonstrated above, despite the mask of its apparent uniformity, we can still trace within Biblical Hebrew distinctive linguistic innovations that have left their mark on the historical development of the language. Such changes and modifications did not occur overnight, but were part of an ongoing dynamic process extending over quite a long time.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1.

See Yosef Ofer, “The Mystery of the Missing Pages of the Aleppo Codex,” BAR 41:04; Emanuel Tov, “Searching for the ‘Original Bible,’” BAR 40:04; David Marcus and James A. Sanders, “What’s Critical About a Critical Edition of the Bible?” BAR 39:06; Yosef Ofer, “The Shattered Crown, 60 Years After the Riots,” BAR 34:05; Harvey Minkoff, “The Aleppo Codex—Ancient Bible from the Ashes,” Bible Review 07:04.

2.

See Sidnie White Crawford, “A View from the Caves,” BAR 37:05; Steve Mason, “Did the Essenes Write the Dead Sea Scrolls?” BAR 34:06; “A New Dead Sea Scroll in Stone?” BAR 34:01.

3.

See Paul Sanders, “Missing Link in Hebrew Bible Formation,” BAR 41:06.

Endnotes

1.

Although certain phenomena characteristic of the late period at times appear sporadically in earlier compositions, an outstanding accumulation of these features may be found only in the decisively late sources.

2.

Frederick H. Cryer, “The Problem of Dating Biblical Hebrew and the Hebrew of Daniel,” in Knud Jeppesen, Kirsten Nielsen and Bent Rosendal, eds., In the Last Days: On Jewish and Christian Apocalyptic and Its Period (Festschrift Benedikt Otzen) (Aarhus: Aarhus Univ. Press, 1994), p. 192.

3.

For diachronic studies dealing specifically with Late Biblical Hebrew, see Aaron D. Hornkohl, Ancient Hebrew Periodization and the Language of the Book of Jeremiah: The Case for a Sixth-Century Date of Composition (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2014); Avi Hurvitz, “Biblical Hebrew, Late,” in Geoffrey Khan, ed., Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, vol. 1 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2013), pp. 329–338; Avi Hurvitz, A Concise Lexicon of Late Biblical Hebrew: Linguistic Innovations in the Writings of the Second Temple Period (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2014); Eduard Y. Kutscher, “Biblical Hebrew,” in Raphael Kutscher, ed., A History of the Hebrew Language (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1982), pp. 12–86; Robert Polzin, Late Biblical Hebrew: Toward an Historical Typology of Biblical Hebrew Prose (Missoula, MT: Scholars Press for the Harvard Semitic Museum, 1976); Mark F. Rooker, “Recent Trends in the Linguistic Analysis of Biblical Hebrew,” in Ethan C. Jones, ed., Essays in Honor of George L. Klein (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, forthcoming); Angel Sáenz-Badillos, A History of the Hebrew Language (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993), pp. 112–160.