Since it opened last spring at the Israel Museum, the exhibition of finds from the Jewish Quarter excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem has been drawing large and enthusiastic crowds.

And well it should. On display are the exciting results of six years of digging in an area only a few hundred yards from the great Temple Enclosure.

Collected by curator Yael Israeli, the objects in the exhibition date from the Herodian period,a when the area excavated comprised a fashionable and wealthy residential section overlooking the Holy Temple. The choice finds, on public display for the first time, are numerous and beautiful, varied in form, and rich in decoration. They afford a unique glimpse into the life of the rich and the powerful at a critical moment in history both for Jews and for Christians.

The author of this article, Professor Nachman Avigad of Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology, has directed the excavations described in this article almost continuously since 1969—and they are still in progress. This article has been adapted from the exhibition catalog prepared by Professor Avigad.—Ed.

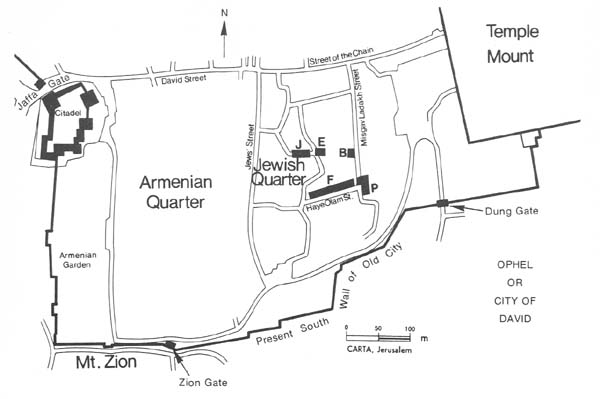

The area now known as the Jewish Quarter of the Old City lies on the “Western Hill” of Old Jerusalem, on which the “Upper City” stood in Second Temple times. This high broad hill is twin-peaked: The western rise is the higher of the two and is now mostly occupied by the Armenian Quarter; the northeastern knoll is presently covered by the Jewish Quarter. The Jewish Quarter overlooks the Temple Mount to the east from which the narrow “Eastern Hill” juts southward (today often called the “Ophel Hill”), the site of the earliest Jerusalem, the “City of David” (see map).

The City of David and the area adjacent to the Temple Mount have been the principal objects of archaeological expeditions since the beginnings of modern research in the city, over a century ago. Numerous excavations and investigations have been made there, and thus most of the knowledge of the material remains of ancient Jerusalem is generally related to this Eastern Hill and to the Temple Enclosure.

In recent years, our knowledge of this part of Jerusalem has increased considerably through large-scale archaeological excavations—in the 1960’s by the British expedition headed by Dame Kathleen M. Kenyon on the Eastern Hill and since 1968 by the expedition headed by Professor Benjamin Mazar adjacent to the Temple Enclosure. All these sites lie within the “Lower City” of Jerusalem, as it was known in the Second Temple days.

In the “Upper City” on the Western Hill, archaeological excavations have previously been carried out mainly on the periphery, to determine the course of the city walls and other fortifications. The interior of the city, that is the residential quarters lying mostly within the area of the present Old City, had not been excavated (except for very minor soundings) for, in the densely built-up areas, few spots remained sufficiently open for archaeological investigation. This was especially so within the Jewish Quarter, where there was even less open space than in the other quarters.

Thus, not even a trial sounding had been carried out within the Jewish Quarter and, archaeologically speaking, nothing was known of this part of the city which, the ancient literary sources suggest, was one of the most important residential areas.

Thus, methodical, stratigraphical excavations in the Jewish Quarter could reveal for the first time the history of settlement in the Upper City throughout the ages; the archaeological findings could enable a study of the material culture of the city in its various facets: urban planning, residential architecture, monumental architecture and art, crafts, and articles of every day use. The opportunity to undertake such an excavation presented itself when reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter, which had been largely destroyed during the 19-year Jordanian occupation of the Old City, began following the Six Day War in 1967.

Jerusalem’s long and variegated history has included many destructions and rebuildings. Each period has provided its quota of ruins. Our excavations have revealed that the earliest stratum of settlement on the Western Hill dates from the Israelite Age (Iron Age II, 8th-early 6th centuries B.C.). In this stratum, few building remains were found, for in subsequent periods builders gnawed away at them for use in their own construction activities. The most important find of this period is a most impressive segment of a city wall, 23 feet thick (see illustration), and a massive fortification structure resembling a tower, preserved to a height of over 25 feet (see “Found in Jerusalem: Remains of the Babylonian Siege,” BAR 02:01). In addition, we have uncovered some remains of buildings and smaller objects. All of this indicates that Jerusalem indeed had already spread beyond the confines of the City of David on the Eastern Hill and on to the Western Hill in the period of the First Temple (which was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.). This new part of the city was apparently the Mishneh (or “Second Quarter”) mentioned in the Bible. (2 Kings 22:14; 2 Chronicles 34:22; Zephaniah 1:10) Thus, the area of the Jewish Quarter was already enclosed within the city walls in the period of the later kings of Judah, possibly beginning in the days of King Hezekiah (c. 700 B.C.).

The excavations in the Jewish Quarter reveal a stratigraphic-chronological gap from the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem until the 3rd century B.C. No archaeological remains of the Persian period have been found. This can be explained by the fact that, after the Return from the Babylonian Exile, the population of the city was small, and settlement concentrated within the City of David, the Western Hill remaining uninhabited over an extended period of several centuries.

The absence of remains from the Early Hellenistic period is more difficult to clarify. Only in the days of the Maccabees (the Hasmonean Period) do we again find building remains, mainly of a defensive nature. Of these, a tower of the city wall was uncovered just south of the Street of the Chain. (See “Found in Jerusalem: Remains of the Babylonian Siege,” BAR 02:01). This tower appears to have belonged to the northern course of the “First Wall”, the early wall described by Josephus as running from the Hippicus Tower (the present Citadel) eastward to the “Xystus” adjacent to the Temple Mount (Wars of the Jews, V, 4, 2). This was the last wall breached by the Romans when they destroyed the city in 70 A.D.

The most extensively preserved occupational stratum is of the Herodian period. This was an era of expansion and splendor in Jerusalem, known till now mainly through such monumental constructions as the Temple Mount, fortifications and the water supply system.

The excavations in the Jewish Quarter have revealed a different Jerusalem, one of daily life, a residential area of the city of which very little had previously been known. The picture is still far from complete. But instead of total ignorance, we now possess a wealth of new material.

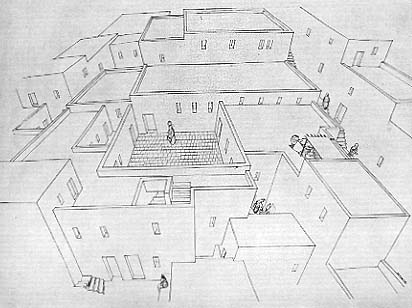

The earliest house uncovered flourished in the days of Herod the Great, although it may have been built earlier, toward the end of the Hasmonean period. The entire plan of this house is preserved: It covers over 2,000 square feet (see plan). It includes a series of rooms arranged around a central courtyard. Into the floor of the courtyard, four ovens were sunk. A large reservoir, accessible through a broad stairway, partly vaulted over, occupies much of the courtyard; beside this there is a smaller cistern. Near the entrance to the reservoir is a stone with a bowl-like depression; this was most probably used for washing the feet prior to descending into the pool (the “footbath” referred to in the Mishnah,b Yadaim 4:1).

In the western wall of the house, which was preserved to a height of almost 5 feet, are three niches which had been used as wall cupboards for the household crockery, as is indicated by one niche, in which many broken pottery vessels were found.

The wealth of this household is indicated not only by its spacious plan but also by the pleasing vessels found inside, such as a fine set of red terra sigillata ware, beautifully designed (see illustration). A group of large amphorae bearing Latin inscriptions indicates that the occupants filled their craving for wines imported from Italy. (Jewish law prohibits drinking of wine made by Gentiles, but this prohibition was apparently ignored.—Ed.) For table use, the wine was decanted into flasks of asymmetrical shape, many of which have been found in the house.

Although no frescoes or painted walls were found in this house, such decorations were common in other houses of the period. In one room of a house dubbed “The Mansion”, a frescoed wall was preserved to a height of 8 feet. The ornamentation includes red and yellow panels, with a schematized imitation of architectural motifs. The fresco and stucco ornamentation in the house attempts to imitate the decorative style of Pompeii and other Hellenistic sites in Asia Minor.

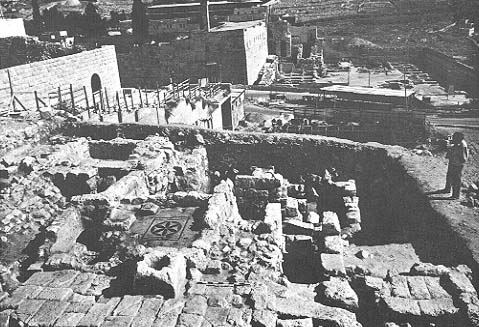

“The Mansion” also includes a large number of water installations, indicative of the considerable demands placed upon the water supply. The great expanse of roof and courtyard areas seem to have sufficed for gathering the requisite quantities of water from the annual rainfall into the many deep cisterns of the house (see outside view of “The Mansion”). These cisterns were hewn into the bedrock. (All of the excavated houses contained at least one cistern.)

Many of the houses also contained a ritual bath (mikvah; pl. mikvaot). These small, open pools with several steps, were used for bathing and ritual immersion, and indicate adherence to the laws of ritual purity.

“The Mansion” as well as most of the other homes from this period were burned and destroyed at the time of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. The burnt layer in one house (known as the “Burnt House” or “House of Kathros”) was not disturbed by later building activities. Everything remained just as it was after the fire and destruction. The debris which filled the rooms contained fallen, scorched masonry and wooden beams charred by the conflagration. Thick ashes covered numerous small objects which had been in the rooms—common pottery vessels, such as cooking-pots, amphorae, flasks, jugs and juglets; small perfume bottles; stone vessels like large vases, bowls, “measuring cups” and covers; mortars and pestles of basalt; querns and stone weights.

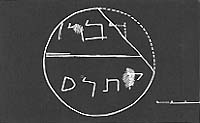

One of the stone weights in the “Burnt House” was incised with an Aramaic inscription: [Of] Bar Kathros” (see drawing). The Talmud mentions the Kathros family as one of the four large priestly families abusing their status in the granting of duties within the Temple and exploiting the people (Pesahim 57a): “Woe unto me for the House of Kathros … who are high priests, and their sons are [Temple] treasurers, and their sons-in-law are [Temple] officers, and their slaves beat the people with rods.” Our Bar Kathros was probably of this family.

Leaning in a corner of one of the rooms of the “Burnt House” was an iron spearhead, as if ready for use. Nearby, the skeletal remains of the right arm of a woman was resting against the wall of the kitchen; apparently she had been killed in the conflagration.

We can even determine the day on which the House of Kathros was destroyed, for Josephus relates that the Upper City held out a month after the burning of the Temple (on the ninth of Ab); the Romans assaulted the Upper City, conquered it and put it to the torch “on the eighth of Gorpeius (Elul), at dawn” in 70 A.D. (Wars of the Jews, VIII, 5).

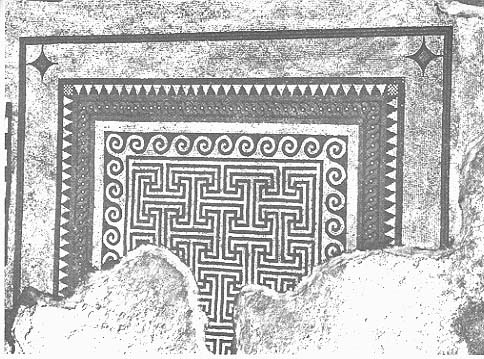

Many of the excavated houses contained mosaic pavements. These are the earliest of their type in Jerusalem, and are the first in this city which can be ascribed to the period of the Second Temple (contemporaneous mosaic pavements have been found at Masada and Jericho). Their true distribution and quantity can hardly be determined, for most of the pavements of the buildings were disturbed and can no longer be studied. However, mosaic floors were apparently in fairly wide use in this well-to-do residential quarter soon after their introduction into Jerusalem.

In one building three mosaic pavements were found, two in dwelling rooms and one in a bathroom. Most of the mosaic pavements are in bathrooms, dwelling rooms or corridors connected with the use of water. Two of these pavements include a geometric, compass-drawn rosette pattern (see illustration). The ornamentation is simple but pleasing to the eye.

No faunal motifs were found in the mosaic pavements (a situation also reflected at Masada), indicating a strict adherence to the Biblical prohibition against images.

Painted plaster and frescoes were quite common throughout the country in the Herodian period. Few traces of them had been found, however, and beyond the motif of plain, colored panels or panels imitating marble, little was known of wall-painting in the Holy Land. Excavations in the Jewish Quarter have changed this picture, enriching the repertory considerably.

The wall-paintings in the Jewish Quarter are mostly in the fresco technique; that is, painted on fine plaster (which contains powdered marble) while it was still wet. The painted surface is entirely smooth, the paint being absorbed into it; the paint does not peel, rub or wash off. It is an efficient (though expensive) technique.

Painted plaster using the so-called secco technique is executed after the plaster is dry—a simpler and cheaper method. The paint is laid down over regular, dry plaster—leaving a rougher surface, the paint remaining on top, later readily peeling or rubbing off.

The most common scheme in the wall paintings found in the excavated houses was a division into square and rectangular panels. Warm colors like red, yellow and brown were most common, but occasionally green, black and other colors were used. The lower part of the wall always bore these painted panels (a dado). Often the panels are ornamented in what is called an “imitation marble” motif.

In “The Mansion” an almost complete wall was preserved. It was entirely covered with painted panels, including painted imitations of windows and other decorative architectural elements.

Floral motifs were also common—a frieze of stylized palmettes and buds or plaited garlands with bunches of apples and pomegranates. The naturalistic depiction of the latter reflects an impressionistic realism typical of the earlier wall-paintings at Pompeii.

Most of the furniture in the houses was made of wood and thus has not survived. However, for the first time in this country, stone tables have come to light—this is the only actual furniture now known to us from the period of the Second Temple (see illustration).

These decorative stone tables were found in almost every house in this residential quarter of Jerusalem. Fragments of this type were found in other excavations in Jerusalem, but were not recognized for what they were. However, examples are well known at Pompeii and other Hellenistic-Roman sites. They usually stood in gardens and reception rooms, and were used for refreshments for guests or for displaying objets d’art.

The large number of stone vessels in the Jewish Quarter Excavations (as well as in other excavations in the city) indicates a developed and flourishing stone industry in that period. Stone vessels were much more expensive than pottery, but their common use (see illustration) can be explained by the rulings of the Sages concerning purity: for stone vessels were not susceptible to uncleanness; they could therefore be used without going through the elaborate re-purification process.

These stone vessels vary widely, from large to small, from kitchen utensils to table ware, from storage vessels to serving dishes. Especially interesting are the large vessels (25–30 inches high), vase-like on a high foot, finely designed and worked (see illustration). There are also many shallow and deep bowls and cups—all turned on a lathe. Of cruder finish are the handmade deep and square bowls. Also handmade are the measuring cups, well-known in all excavations in Jerusalem. Finally, the excavations uncovered various flat plates and trays, round and rectangular, often with finely ornamented handles. Delicate examples of this type are made from imported stone.

However, the most common household items are, of course, pottery vessels. The most common forms are those which were in general use in the house, that is, cooking-pots and storage amphorae. But most of these vessels were not discovered in kitchens or store-rooms—which are generally found both destroyed and looted—but rather in reservoirs and cisterns which came to be used as refuse pits. In one disused cistern was found some 30 intact and over 600 smashed cooking-pots (the calculation was based on the number of handles found).

Among the most unusual pottery were several small painted bowls, occasionally denoted “pseudo-Nabatean”. They are thin-walled and ornamented inside with a variety of floral patterns in red, brown or black (see illustration). The similarity with Nabatean bowls is only general for they differ in both ware and style of ornamentation. So far, such painted bowls have been found only in excavations in Jerusalem, and they can properly be termed “painted Jerusalem bowls”.

In contrast to the local pottery, which lacks all painted slip, the imported wares of the Eastern terra sigillata family are outstanding. The group of plates, bowls and jugs is quite impressive in its fine forms and deep red slip. These vessels are luxury wares, not found in every household.

The lamps found in the excavations represent the entire variety of shapes common in the Late Hellenistic and Early Roman periods, with a scattering of more unusual types. The earliest of these are the lamps made from small bowls, with their rims pinched to form a nozzle (the “Hasmonean” type). These continue the local, open lamp tradition of the Iron Age.

Subsequent to these chronologically are the lamps generally denoted “Herodian”, wheel-made, with spatulate nozzles; they are thin-walled and smooth, and were in general use in the 1st century A.D. (see color illustration). This type can be called the standard lamp of the 1st century A.D. in Eretz-Israel.

Several unusual glass finds indicate that the inhabitants of Jerusalem could obtain the finest glass products of the period, such as the splendid jug made by the Phoenician glassmaster Ennion. This vessel was found broken and distorted by the conflagration which destroyed “The Mansion”.

The Jewish Quarter Excavations were fortunate also in another unusual discovery of far-reaching importance for the study of ancient glass production: Below a paved street, a complex of reservoirs and baths was uncovered; in the fill of one of the reservoirs was a heap of refuse from a glass factory. The glass fragments have been distorted by heat. But it is clear that the glass was not only molded, but blown. This is some of the very earliest blown glass ever discovered. We have dated the level in which the glass refuse was found to c. 60–50 B.C. (It is generally believed that blown glass was invented by some unknown genius who lived in Phoenicia, just north of Israel, within, at most, a few decades of the blown glass found in Jerusalem. Thus, within a very few years of its discovery blown glass was being manufactured locally in Jerusalem.—Ed.) Further study of this glass refuse should also shed important new light on the history of glass manufacture technology. Here for the first time, we have evidence from the transitional phase of those two major glass manufacturing techniques—molding and blowing.

Iron objects were also found, generally in an advanced state of disintegration. Thus it is most often difficult to ascertain their original forms. Most of the iron finds are nails, apparently used to fasten the beams of ceilings. A group of iron tools is noteworthy, including axes and adzes, found together with a large iron key. More special are small bronze bells, cymbals, furniture and casket fittings, parts of locks and door-bolts, hooks, nails and angles. Of particular note are small, intricate keys.

Bone-working was a well developed craft, this material being used for delicate utensils and ornaments such as needles, pins, ornamental spoons, handles, awls, spatulae and buttons.

The coins from the Jewish Quarter Excavations can be divided into two groups: individual coins found in clear contexts and strata; and large groups of coins, hoards or caches—which are of greater significance than the isolated finds. The finds include Ptolemaic coins from the 3rd century B.C., Seleucid coins of the 2nd century B.C., and Hasmonean coins down till the conquest of Jerusalem by Herod in 37 B.C. In later strata there was a plethora of coins of Herod the Great and his son, Archelaus (37 B.C.–6 A.D.), as well as coins of all the Roman Procurators of Judea (6–59 A.D.).

Certain architectural fragments found in the Jewish Quarter indicate the existence of public buildings which themselves have not been found. An especially fine capital resembles capitals found at the Tomb of Queen Helena (so-called “Tombs of the Kings”) in Jerusalem (see illustration). A huge Ionic capital was also found, together with several drums from the column. The girth of these drums indicates that the column itself must have stood to a height of between 30 and 35 feet.

Perhaps the single most stunning find in the excavation was a menorah, the seven-branched candelabrum, incised on a fragment of plaster. It is about 8 inches high and has tall branches, a short stem and a triangular base—all ornamented in a stylized astragal pattern (see illustration). This is the earliest depiction of the candelabrum in the Temple ever discovered, and was incised on a wall of a house as a symbolic ornament at a time when the actual Temple Menorah was still in use, only a few hundred yards away.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Herod the Great began his reign in 37 B.C. and died in 4 B.C., but the period which bears his name is usually considered to extend to 70 A.D. when the Romans destroyed the Second Temple. The Herodian period thus includes the Jerusalem of Jesus’ time.