After several seasons of excavations at Megiddo, I believe I have proven that the two groups of buildings commonly referred to as “Solomon’s Stables” are not Solomonic but must date to approximately the reign of Ahab.1 However, I do not challenge the conclusion of the original Megiddo excavators that the buildings are indeed stables. It seems to me that the association with Ahab is quite consistent with the testimony of Shalmaneser III, according to which Ahab is credited with commanding a great number of chariots2—more, even, than were in possession of several of the kings around him.

Recently, Professor James B. Pritchard published an article in which he contests the identification of these buildings as stables, although he does accept my conclusion regarding their date.3 We should be grateful to Professor Pritchard for raising the issue, because it is wise, from time to time, to give new consideration to points heretofore universally agreed upon. It seems to me though that Pritchard’s argument does not hold and that the conclusion of the original excavators that these are, in fact, stables is still valid. It is true that the original excavators at Megiddo were influenced by their belief that the buildings were Solomonic, by the fact that Biblical sources mention Solomon’s chariots, horses, and the chariot cities that he built (1 Kings 10:26), but it is also appropriate to point out that they based their assertion that these buildings were stables on the buildings themselves.4

I would now like to take issue with some of Pritchard’s basic conceptions:

Pritchard bases his contention that the buildings in Megiddo are not stables on the similarity between the plan of the buildings—that is, long halls with two rows of columns—and the plan of the Iron Age buildings uncovered at Hazor and Tell es-Sa’idiyeh (to which we must now add those recently discovered in Beer-Sheva). Based upon the finds in these buildings to which Pritchard compares the Megiddo buildings, it is reasonable to assume that in their later stages they served as storehouses, or the like, and not as stables. However, the architectural resemblance is not sufficient to establish the nature of the Megiddo buildings, since, as Yigal Shiloh has correctly shown5, the archaeological remains can indicate merely any typical rectangular building that required a ceiling support across its width. I will refer to these other buildings later, but it is worthwhile mentioning here that unlike the buildings at these other locations, the southern complex of buildings at Megiddo adjoined a huge courtyard, at the center of which was found a sunken watering trough. It is easy to explain this large trough—as the excavators of Megiddo did—in the context of stables, but its purpose is unclear if these buildings are to be regarded as storehouses.

The characteristic feature of the buildings at Megiddo—in contrast with the similar buildings at the other locations—consists of manger-like units that were discovered between the pillars6. These mangers were made from large, hewn stones, whose tops had been chiselled out in a rectangular fashion. It was these troughs that led the excavators of Megiddo to conclude that they were, indeed, dealing with stables. Moreover, anyone who looks at these mangers, which were sometimes raised by being joined to the wall, or placed on top of benches to elevate them, will be easily convinced of the great effort made by the builders of Megiddo to install them. All who would criticize the “stable theory” must first explain the function of these mangers situated between the pillars. Moreover, many of the pillars had been perforated to produce tethering holes. Pritchard fails to explain the purpose of these mangers; indeed, his reasoning serves merely to negate his conclusions. He says that the shallow depression at the top of the stone blocks, which is only about six inches deep, is not appropriate for a manger. In his own words: “It is obvious that such a shallow trough—only six inches—could scarcely be the most practical container for grain or other food for a horse.”7 However, I have discussed this point with several experts on horses, and they all state that the mangers at Megiddo conform to the best requirements, even modern ones: specifically, a high manger, so that the horse need not bend down; and a shallow trough to fix a precise measure of fodder. In addition, the great weight of the mangers—several hundred pounds—prevented the horses from knocking them over while feeding.

However, Pritchard’s principle argument is that stables did not exist in ancient times.

“Is there evidence” he asks, “[that in ancient times] horses were kept in stables, and not in open enclosures? As far as I know there is no evidence in the ancient Near East for stables, especially buildings that resemble in plan those in use in the contemporary West.”8

This conclusion seems strange indeed, for logic itself forces us to assume that in ancient, as well as modern, times kings would erect structures for their prized horses, to protect them from the cold and the rains that cause such heavy damage in the Near East, and in northern Israel in particular.

Fortunately, we need not be concerned with hypotheses. We have a great deal of documented evidence, not just that stables were necessary in ancient times, but that they included mangers which bear great resemblance to those discovered at Megiddo.

From an examination of the buildings at Tell El-Amarna, it can be clearly seen that several served as stables, for they contain both mangers and tethering pillars. This is dealt with at length in Badawy’s book, from which I quote:

“Stables [for the horses] feature a built-up manger with tethering stones on one side and a feeding passage on the opposite side”.9

“The police barracks, identified as such on account of the extensive accommodation for horses … The entrance leads into a large central court surrounded by mangers and tethering stones with a row of deep contiguous stables on the east”.10

Pendlebury also describes stables belonging to the noble estates at Tell El-Amarna:

“The stables often occupy part of one side of an estate. They consist of a cobbled standing space for the horses with a tethering-stone let into the ground. The square mangers are built up and behind them runs a feeding passage so that they can be filled from the outside.”11

It is interesting to compare his description of the royal stables at Tell El-Amarna with the buildings at Megiddo.

“ … The great parade ground with a deep well in the middle, long cobbled stables with mangers and tethering stones to the east”.12

The royal stables uncovered at Ugarit13 are especially important, for not only were mangers discovered there which are identical to those at Megiddo, but also a handsome horse’s bit.14

These mangers at Ugarit were placed on top of a stone bench for proper elevation. The measurements of the depressions in the mangers are: 0.40 meters × 0.80 meters and 0.40 meters × 1.00 meters—almost exactly the same as the managers at Megiddo.15

These findings are sufficient to repudiate Pritchard’s assertion that stables were not built in ancient times.

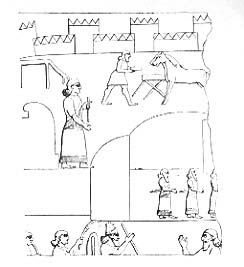

But there is more: One of the orthostats from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud16, contains a unique carving (see illustration) showing four royal chariot horses standing in a splendid stable, erected in a camp near the field of battle. From this we can conclude that even under field conditions prized horses were lodged in covered stables. Two of the horses in the illustration are feeding from a manger that greatly resembles those at Megiddo, both in form and in measurement. Note that in this illustration, the depression in the manger is shallow, just as at Megiddo. A shallow depression in a manger may also be seen on a tablet in the palace of Tiglath-Pileser III, which depicts a portable manger that was used in the field and placed on wooden legs to elevate it (see illustration).17

Finally, my students Shulamit Geva-Rosolof and Barch Barondel have called my attention to a tablet (see illustration) and a wall-drawing (see illustration) from Tell el-Amarna which clearly depict mangers similar to those at Megiddo and Ugarit. Moreover, the artists, like those who did the Assyrian reliefs cited above, stress that the depressions in the mangers are shallow.

From all of this data, it seems plausible to conclude that the findings at Megiddo represent the only example discovered to date of what the Scriptures refer to as a “chariot city”.18 Clearly, in a city of this type, it was necessary to have magazines for the storage of fodder, and it is possible that a second story above the stable wings, served such a purpose.19

The existence of basins or mangers between the pillars at the other sites, especially at Beer-Sheva, suggests that buildings such as those at Beer-Sheva were originally constructed as stables, not that the buildings at Megiddo were storehouses. In support of this theory we may point to the tethering holes recently discovered on several pillars at Beer-Sheva,20 found on the floor of the adjoining halls. Zeev Herzog’s theory that the mangers were used to feed donkeys while their burden was being unloaded21 is not plausible,—for why would the animals, together with their dung, be brought into food stores, when it was possible to discharge their loads within a few minutes, and to feed them outside?

The varied pottery finds in the buildings at Beer-Sheva testify only to their function in later stages of use. We may also ask whether, even at this late stage, the buildings, in fact, served as storehouses in a technical sense. Among the approximately 150 vessels discovered in one of the rooms of these “storehouses”, only about a third were storage jars, while the rest included 21 cooking pots, 35 bowls, 8 flasks, 8 decanters and the like. Many millstones were also found in the buildings.22 Doesn’t this indicate that in their later stages the buildings served as barracks for garrisoned troops and as food stores for the garrison?23 It would appear that the kings of Israel and Judah originally planned their military cities for the stationing of cavalry or chariot detachments to be used in times of need and that stables were erected at the very outset; when the stables were no longer needed, they were used as accomodations for the garrisons and for the food stores they would require.a

MLA Citation

Endnotes

See Y. Yadin, “Megiddo of the Kings of Israel”, Qadmoniot Vol. 3 (1970), p. 38; Y. Yadin, Hazor (The Schweich Lectures, 1970), London, 1972, pp. 150 ff.

Y. Yadin, “Hazor, Gezer and Megiddo in the Days of Solomon” in A. Malamet (ed.), Days of the First Temple, Jerusalem, 1962, p. 103.

J. B. Pritchard, “The Megiddo Stables—A Reassessment”, in J. A. Sanders (ed.), Near Eastern Archeology in the 20th Century—Essays in Honor of Nelson Glueck, New York, 1970, pp. 268 ff.

P. L. O. Guy, “New Light from Armageddon,” Oriental Institute Communications, IX, Chicago, 1931; R. S. Lamon & G. M. Shipton, Megiddo, I, Chicago, 1939, pp. 32ff, 41ff.

Y. Shiloh, “The Four-Roomed House—A House Type from Israel,” in Eretz Israel XI, Jerusalem, 1973, p. 277.

A. Badawy, A History of Egyptian Architecture—The Empire, University of California Press, 1968, p. 151.

Ibid., p. 125 (Additional bibliography will also be found here). Regarding cattle-stalls, see N. de G. Davies, The Rock Tombs of El Amarna, London, 1903, pl. XXIX. See also H. Ricke, “Der Grundriss des Amarna Wohrhauses”, Osnabruch, 1967, p. 47.

Ugaritica, IV (1962), p. 3; Fig. 13, p. 18; Syria, XIX (1938) pp. 313 ff.; XX (1939), p. 284; Illustrated London News, June 6, 1940, p. 26.

Professor Schaeffer did not give me the measurements for the depths of the depression, but one is able to see clearly either from the plan, or from the photographs that the mangers are shallow, and that the depressions’ measurements are similar to those of the mangers at Megiddo.

A. H. Layard, The Monuments of Nineveh, London, 1839. See R. D. Barnett, Assyrian Palace Reliefs, London (n.d.), pl. 21, for a good photograph of this tablet.

Ibid., Plate 63; See also, R. D. Barnett & M. Falkner, The Sculptures of Tiglath Pileser III, London, 1962, Pl. LXIII, p. 24.

The existence of chariot cities is also attested in a document of Sargon II, in which is described his “Eighth Campaign” to Ararat. One of the passages states: “Their inner walls are strong, the outside walls are strongly built, their trenches are deep and enclosed above. Inside there are horses, a reservoir—the royal horses stand in the stables, and are well fed all year round.” See, F. Thureau-Dangin, La Huitieme Campagne de Sargon, Paris 1912, p. 130, illustrations 188–191; D. D. Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylon, II, Chicago 1926, p. 159. I am grateful to N. Newman for this reference, and for the translation cited above. We also learn of the existence of stables for horses and mules from the neo-Assyrian documents, recently published, which have been found at Nimrud, and date to the end of the 8th century. See also, J. V. Kinnier-Wilson, The Nimrud Wine Lists, London, 1972, p. 53 (“The King’s Stables”). I am grateful to Professor A. Malamat for this information.

“Hadashot Archiologiyot”, 48–49 (1974), p. 84. To these stable complexes must be added the building discovered by J. Naveh at Khirbat al-Muganna, in which were also found rows of pillars in which tethering holes had been perforated; IEJ, VIII (1958), pp. 87ff. 94; Figs. 2–3. Naveh’s assertion that the row of columns which is preserved in the central and western halls is located in the center of the halls, is inaccurate; the row is closer to the northern wall, and from this we are able to reconstruct the plan of these buildings, so that it matches very closely the reconstruction of the buildings at Megiddo and Beer-Sheva. It is worthwhile pointing out that these buildings, like their counterparts at Megiddo and Beer-Sheva, are situated in the city gate area, which is an appropriate location for horses’ stables.

Ibid., p. 15. The variety of the finds surprised the excavator: “Such a multi-varied composition is surprising in a communal storehouse, for we would expect to find vessels for stock-piling (food) of a uniform shape;” “The rest of the vessels do not belong to a category that one expects to find in storehouses.” See Y. Aharoni, Hafirot Umehkarim, dedicated to Sh. Yeivin, Tel-Aviv 1973, p. 17.

Z. Herzog’s explanation for the existence of these vessels does not reconcile with the character of the find: “Products were brought in, measured, prepared and then taken out according to the needs of the administrative unit (civilian or military) for which they were intended.”. Was the food really taken out in bowls and jugs?