Images of God in Western Art

026

The Bible contains many references to God’s human attributes. Not only does he get angry and threaten, he also cajoles and forgives. We learn that he has nostrils that “blast” (Exodus 5:8), an arm that “stretches” (Deuteronomy 5:15), a finger that “writes” (Exodus 31:18), lips that “open” (Job 11:5) and hair “like pure wool” (Daniel 7:9). What is more, we know that God “created man in his own image” (Genesis 1:27).

To this extent the Bible encourages the reader to visualize God. On the other hand, the Bible also prohibits image-making, particularly of God. The Second Commandment warns that “Thou shalt not make any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under 028the earth” (Exodus 20:4, Deuteronomy 5:8).

Despite these strictures, however, God has frequently been depicted in art. The form of the imagery has been determined by the particular artistic tradition and the theological perspective of the artist’s time and place, as well as by the artist’s own powers of invention.

Perhaps the earliest visual reference to God in art is his right hand, the Dextra Dei. The Old Testament repeatedly uses the verbal image of God’s right hand. The Song of Moses (Exodus 15:6) declares:

“Thy right hand, O Lord, glorious in power. Thy right hand, O Lord, shatters the enemy.”

Psalm 118:16 in language no less explicit says:

“The right hand of the Lord is exalted; the right hand of the Lord does valiantly.”

The Hebrew word for hand is yad. Yad also signifies “power.” This double meaning may explain why artists have so often used a hand to express God’s power in human affairs.1 It is always God’s right hand that is represented, the right being the side of righteousness and of those delivered from evil.

The right hand of God appears for the first time in the wall paintingsa at the third century A.D. synagogue of Dura-Europos in Syria. At Dura-Europos, among the many Old Testament scenes discovered in 1932, we find several in which a right hand, reaching down from above, symbolizes God. God’s hand appears holding the hair of Ezekiel as he places him in the Valley of the Bones; in another episode, he hand of God stretches over Ezekiel as he restores the bones to life (above). God’s hand extends toward Moses in the scene with the burning bush, and in the painting of the Israelites crossing the dry sea, God’s power is again expressed by the image of his hand.

The hand image persists until the 14th century as one of the images for Yahweh of the Old Testament and God the Father of the New Testament.

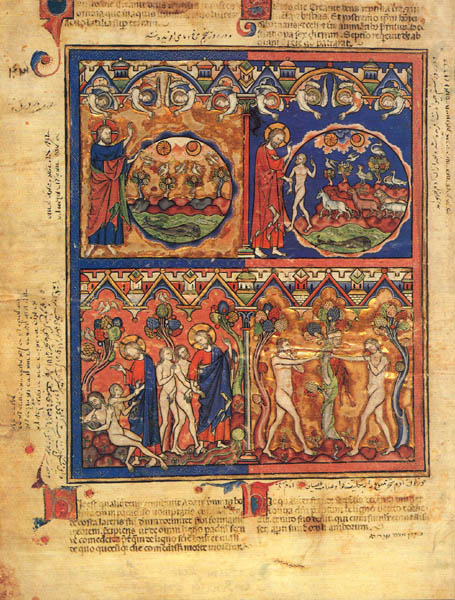

Between late antiquity and the early Renaissance, and particularly in the 13th century, God is frequently represented in human form as the second person in the Trinity. Here he is depicted as a young man rather than as elderly, and he has a halo with the cross within it. In the beautiful page from a manuscript (see photo of manuscript page) painted by Parisian artists in about 1250, we see an example of this kind of representation of God; he is portrayed as a youthful man, with brown hair and beard and with the 032cruciform halo.

The manuscript page illustrates one of the central and most profound texts of the New Testament: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him” (John 1:1). How could the artist suggest the thrust of this declaration visually? He did so by giving to the creator the image and attributes of Jesus Christ, so that it is Christ the Son with his cruciform nimbus who performs the great acts of creation and separates the light and the darkness, who creates heaven and earth, who creates Adam and Eve.

The cycle of paintings that forms the great altarpiece triptych by Jan and Hubert Van Eyck, completed in 1432 in the Flemish city of Ghent, mirrors the whole Christian universe of that time. The central figure—a mature young man (see photo of figure on triptych from Ghent)—reflects the imagery of the King of Kings in the Book of Revelation (Revelation 5:6–12, 7:2–12). This imagery was interpreted by Augustine to refer to all three persons of the Trinity: “In these words neither the Father is specially named, nor the Son, nor the Holy Ghost, but the blessed and only Potentate, the King of Kings and Lord of Lords, the Trinity itself.”2 It is, this composite King of Kings that we see in the Ghent altarpiece.

Certainly the grandest vision of God comes from the Renaissance period and is that of Michelangelo. With sublime self-assurance he created the image of an all-powerful God, endowed with power, limitless strength and mobility (see above and photo of ceiling of the Sistine Chapel).

At the same time in the 16th century that Michelangelo was painting his Sistine Chapel frescoes in Rome with the image of the creator as all-powerful and virile, moving through his heavens and over his earth with a controlled dynamism, a north European artist known as Matthias Grünewald was creating another image of God (below). How spectral, and insubstantial, how remote and spooky this God seems when contrasted with Michelangelo’s muscular activist who is so at home in his own firmament. Yet both images were painted about the same time and come within the category of God the Father represented as an elderly man.

Images of God continue to appear in the great Baroque ceiling paintings, in the churches of the 17th century, and also in 18th-century altar and ceiling paintings. But by the 19th century, the frequency and quality of such works diminished.

Influenced by Michelangelo’s image of God, yet having quite different content, is William Blake’s Elohim Creating Adam (see photo of Elohim Creating Adam). It is an extraordinary and memorable vision of a winged God giving life to Adam who is entwined in the coils of a serpent. William Blake (1757–1827), like Rembrandt, obsessively illustrated the Bible. Also one of the great English Romantic poets, Blake is probably most well-known as an artist for his masterpiece, the illustrations for the Book of Job.

034In the late 19th century, the American artist, Alben Pinkham Ryder, in his painting of Jonah (see photo of Jonah) gave us one of the last of the God images, not only in American art, but in Western art. Ryder’s God has the special distinction of being the only left-handed God known to me. If the Book of Jonah is read with Ryder’s painting in view we will appreciate that the artist is not depicting the drama of Jonah’s flight from God, nor his shipboard experience, nor even what happens when Jonah is thrown into the sea and is swallowed by the whale. After that happened, “the sea ceased from its raging” (Jonah 1:15). It is then that the artist enters the scene. Ryder depicts Jonah’s experience of God when he prays to the Lord from the belly of the fish. Here the Lord, answering his prophet Jonah, enters the drama of flight, and is an active protagonist in salvation. The Lord is not an all-seeing, all-knowing overseer whose presence guarantees the right outcome. Ryder represents him as a force, as much psychic as physical, enlisted on the side of the prophet. Ryder’s rendering of God is a marked transformation of the tradition; Michelangelo’s God works by fiat; William Blake’s late 18th- to early 19th-century visualizations represent a God in whom good and evil are joined. Ryder, unlike his predecessors, represents a God who is involved in the event, and whose omnipotence is exercised in the throes of participation.

Does the image of God appear in 20th century art? The answer is “no,” but a qualified “no.” God does appear in a small group of works by artists like Käthe Kollwitz, Ernst Barlach, Emil Nolde and Paul Klee. These artists express their personal and individual piety, rather than the commonly held faith of a believing community. Their works were created 035out of an inner necessity, not to fulfill church commissions, as was the case in the medieval, Renaissance and Baroque eras. Käthe Kollwitz’s relief sculpture, In God’s Hands (see the

Let us change the question slightly, however, and ask, Is man’s encounter with God the subject of painting in our century? The answer is decisively “yes.”

Barnett Newman’s 14 paintings titled The Stations of the Cross (see photo of First Station by Barnett Newman) are one of the great cycles of 20th-century painting. They are not concerned with the 14 traditional separate episodes, but rather they express phases of a continuous agony. Their real subject is Jesus’ agonized cry, reiterating the lines of the Psalmist, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (Psalm 22). It is humanity that is crying out of God

Newman wrote a statement of his own reflections on this cry of Jesus:

“Lama Sabachthanib—why? Why did you forsake me? Why forsake me? To what purpose? Why?

“This is the passion. This outcry of Jesus. Not the terrible walk up the Via Dolorosa, but the question that has no answer.

“This overwhelming question that does not complain, makes today’s talk of alienation, as if alienation were a modern invention, an embarrassment. This question that has no answer has been with us so long—since Jesus—since 036Abraham—since Adam—the original question.

“Lama? To what purpose—is the unanswerable question of human suffering.”c

Newman’s Stations of the Cross have no reference to an image of God—nor does God’s image appear in the work of major artists of our time, except that of such German Expressionists of the post World War I period as Kollwitz, Barlach, Nolde and Klee. For those of us who live in the 1980s, the disappearance of the image of God from art seems to be less of a problem than the appearance of God in earlier ages. The feminists of our day are not the only ones who reject the imagery of God the Father as seen Renaissance works of art. Among most of my students and colleagues, the anthropomorphism of the Van Eycks and of Michelangelo seems irrelevant to their religious concerns, if not actively repugnant to their sensitivities.

Does this mean that our magnificent heritage of religious art from the past is accessible to 20th-century believers only in aesthetic terms? Many are inclined to answer “yes.” But all who have seen the original works of art, who have stood in their presence thoughtfully and expectantly, know that what they have felt was not “merely aesthetic.” They have been deeply and strangely moved as the totality of the work of art asserted its power and meaning. The imagery and symbolism—the anthropomorphism— is so embedded within the symphonic totality of design and color, within its depth and breadth and its grandeur of vision, that the observer can only respond in awe and praise.

Moreover, today art historical scholarship is adding yet another level of response to religious art of the past. Art historians are studying the theology, the liturgy, the church history of all periods; and this scholarship enables us, for example, to appreciate the Ghent altarpiece as an embodiment of the religious thought of its place and time.

The late 20th century is not the time, nor is western civilization the place, for the visions of the Van Eycks and of Michelangelo. Our vision, not only of God but of the world, is different from theirs. We see the world in ways unknown to medieval and Renaissance artists. In 1907 Cubism was invented by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. It remained stubbornly grounded in the real world, but it shattered and rearranged that reality. Cubism prepared the way for the development of non-representational art. Although the image of God as we know it from the Van Eycks, Michelangelo and Grünewald, and from numerous lesser artists, has disappeared, religious imagery and symbolism are not dead. Barnett Newman’s stark works stand as witness to the persistence of religious expression in our times.

We live in a waiting period—waiting for the birth of new symbols and new imagery. But this should reference not be a passive waiting. It should instead be a time of experimentation, openness, a passionate and expectant waiting. We must keep alive the religious art and imagery of the past, try to understand it in its own terms and to make it pan of the present, for all new imagery grows out of the fabric of history. At the same time we look forward to a future in which earlier artists building on the past will find ever different ways to visualize the divine.

The Bible contains many references to God’s human attributes. Not only does he get angry and threaten, he also cajoles and forgives. We learn that he has nostrils that “blast” (Exodus 5:8), an arm that “stretches” (Deuteronomy 5:15), a finger that “writes” (Exodus 31:18), lips that “open” (Job 11:5) and hair “like pure wool” (Daniel 7:9). What is more, we know that God “created man in his own image” (Genesis 1:27). To this extent the Bible encourages the reader to visualize God. On the other hand, the Bible also prohibits image-making, particularly of God. The Second Commandment warns that […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

These wall paintings are frequently referred to as frescoes. Unfortunately, they are not; if they were, they would have survived in even better condition. Fresco technique involves applying the paint to wet plaster so the color is partally absorbed into the plaster. At Dura-Europos the so-called al secco technique was used: the paint was applied after the plaster dried. This technique is much easier to execute, but is less durable; the paint may flake off after a time.