The most influential Homer scholar of our generation is Gregory Nagy, Francis Jones Professor of Classical Greek Literature at Harvard University and director of the Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington D.C. Nagy has permanently changed our understanding of the Iliad and the Odyssey. No longer can we think of them as ancient “novels” written by an author named Homer; rather, these epics began as a diverse group of poems, which were passed down from generation to generation by rhapsodes (oral poets) over a period lasting more than a thousand years. So who was Homer? And how did that collection of oral poems evolve into our Iliad and Odyssey, the central literary works of Western civilization? Archaeology Odyssey managing editor Jack Meinhardt and senior editor Sudip Bose visited Greg Nagy at the Center for Hellenic Studies to find out.

Jack Meinhardt: Was there really a man named Agamemnon, in the late-second-millennium B.C.E., whom Homer describes as the king of Mycenae and the leader of the Greek forces in the Trojan War?

Gregory Nagy: No. I can imagine a king by that name ruling Mycenae. I can imagine Greek forces fighting in a Trojan War; I think there were many layers of Trojan Wars. But why his name found its way into Homer’s Iliad may have less to do with any real person called Agamemnon that with the story of Troy as it was taking shape in the course of the city’s many destructions and reconstructions. The reshaping of such a story is more a matter of myth than of historical fact.

In general, we don’t find that historical facts are the kernel of myth but that myth organizes historical facts. Let’s say that Gilgamesh [the hero of a Mesopotamian epic] is a name connected to a known figure who lived in Sumer in the third millennium B.C.E.a I would say this historical Gilgamesh used myth for his own glorification, by basing his identity as a dynast within a sequence of kings. This historical Gilgamesh (if there was such a person) becomes fused with a character who goes on a quest and discovers his mortality and how he might transcend his mortality—the mythical Gilgamesh.

JM: We normally think that the relationship between history and myth works the other way. Perhaps there was an actual figure—a Gilgamesh or an Agamemnon—and over time stories simply became attached to that figure, whether or not there was any original connection.

GN: I think the core is really myth—or the social agenda satisfied by myth.

JM: Is this true of Midas? We know there was a man named Midas who ruled Phrygia toward the end of the eighth century B.C.E. He is attested in contemporaneous Assyrian sources, as well as in later classical sources. Common sense tells us he didn’t turn things to gold by touching them. But he existed.b

GN: It’s a similar phenomenon. Yes, there was a historical figure named Midas. But I would still say that his identity is predicated on earlier Midas figures in Phrygian myth.

JM: You mean Midas-like figures, not figures named “Midas”?

GN: Midas-like figures. My point is that the organizing system of what is being told about King Midas is myth, not history. Myth can use history, but the rules of the game are the rules of myth, not history as we know it.

JM: Was there an Aeolus, the god of winds? Is there any difference between asking if there was an Agamemnon and asking if there was an Aeolus?

GN: There is, because the figure of Agamemnon is dynastic. He interacts with historical realities in a way that makes the Greek “heroic” age something of a reality for the Greeks of the “post-heroic” age.

JM: But do those problems have a historical context? Can we date them in any coherent way? Can we say that Agamemnon, who ruled Mycenae, is associated with problems that accord with Mycenae—or Greek cultural history—at some particular period in history but not other periods?

GN: Well, whenever you look at myth, it’s a system, but it’s a layered system. You have to be archaeological. Some aspects of a myth may be characteristic of one time and place, while other aspects are characteristic of other times and places. In Homeric Greek, for example, any given line may contain two different linguistic forms that can be dated a thousand years apart. If you can do that with the linguistics of a verse, what about the content?

JM: Can you give an example?

GN: Exhibit A: Chariot fighting. As described in Homeric poetry, chariot fighting was used in second-millennium warfare. Around 1200 B.C.E., in the Anatolian plains, nothing would have been more frightening than a mass of chariot warriors ready to attack. In Mycenaean Greek, the word for chariot is hikwia. We find this word hikwia in chariot inventories recorded on Linear B tablets from the palace at Knossos, on Crete. But the word became extinct in post-second-millennium B.C.E. Greek. So in the Iliad you sometimes have people jumping on and off hippoi (horses) in what seems at first to be a kind of virtuoso circus equestrian act. But hippoi is really a placeholder for the earlier word for chariot, hikwia, which has gone out of business.

Once chariot fighting itself was no longer practical, in the first-millennium Greek-speaking world, chariots became metaphorical, cosmological. And they became ceremonial; for instance, chariot-racing may have been introduced into the Olympics around 680 B.C.E. Even in places where chariots were never used—such as medieval Ireland—they became symbols of the heroic world. St. Patrick is depicted as riding around on chariots.

Sudip Bose: The chariots in Homer preserve a memory that may go back to the second millennium and may be specifically associated with the plains of Troy.

GN: Yes.

JM: Is there evidence in Homer of a historical Trojan War, fought in northwest Anatolia? The great Anatolian civilization of the Late Bronze Age [late second millennium B.C.E.] was Hittite. Do the Hittites make it into the Iliad or the Odyssey?

GN: Yes, they do. In fact, I have found one case of a word borrowed from Hittite, or perhaps Luwian [a language closely related to Hittite that was prevalent in western Anatolia]. In Hittite it’s tarpanalli (or tarpassa), which means “ritual substitute.” In Greek it’s therapôn, which is usually translated as “servant.”

JM: Where is the Greek word found in Homer?

GN: In Book 16 of the Iliad. It’s applied in suggestive and unmistakably linked ways to the role of Patroklos [who fights in place of his friend Achilles while Achilles is feuding with Agamemnon] as the ritual substitute for Achilles.

JM: The only example of writing that Manfred Korfmann [director of the Troy excavations] has found in Late Bronze Age Troy is a seal inscribed in Luwian.c Texts excavated at the Hittite capital of Hattusha, in central Anatolia, tell of wars the Hittites fought in western Anatolia against a people called the Ahhiyawans. Many people connect the Ahhiyawans with the Achaeans, a name Homer uses to refer to all the Greek kingdoms.

GN: I accept that.

JM: The Hattusha texts also refer to a Hittite vassal state named Wilusa that fought against the Ahhiyawans/Achaeans. Do you believe that this Wilusa should be identified with Ilios, a Greek name for Troy [the Greek word Iliad means “The Story of Ilios”]?

GN: I accept that, too.

JM: Troy/Ilios is Wilusa?

GN: Yes.

JM: What Homer preserves, then, is not only a memory of a specific battle but a memory of a clash of civilizations—Mycenaean and Hittite—that took place along the Anatolian coast.

GN: This conflict extended all over the Anatolian coast, all the way down to Lycia and the island of Rhodes. And the stories of all the clashes in this extensive and ongoing conflict were concentrated in a single epic setting, Troy.

JM: It’s tempting to think of Homer as a novelist—a Joseph Conrad who lived in the eighth century B.C.E. and whose most famous novels were the Iliad and the Odyssey. But it’s not like that, is it?

GN: No, not at all.

JM: Was there a Homer?

GN: There was a Homer in the minds and hearts of the people who lived by the song culture that was dominated by what we know as Homeric poetry. There was a Homer for the audience of Homer, so to speak.

JM: What were they thinking of when they thought of this Homer? Were they thinking of a person?

GN: They thought of him as a super-poet, as somebody who was so gifted that he was divine.

JM: Were they right?

GN: Well, they were right in admiring the almost divine mastery of the poetry, the Iliad and Odyssey, that they attributed to Homer. It’s just that they were not evolutionists, as I am. They were thinking in mythical terms. Let’s take an example from law. According to Herodotus, the fifth-century B.C.E. Spartans believed that the prehistoric law-giver Lycurgus had presented them with an oral tradition consisting of a perfect set of laws, which they called Cosmos.

SB: Referring to the universe?

GN: Yes, referring to the expansiveness of the universe and to its beauty; the idea of such beauty is preserved in the English borrowing “cosmetics.” But the Cosmos also referred to the social order of Sparta as idealized by the Spartans—the cosmos, as it were, of their society.

SB: Spartan law embodies the rules governing the universe.

GN: Just as the universe works like clockwork, so does the constitution of Sparta. The Spartans would think, Our cosmos consists of our customary laws, our government, and it was all given to us—lock, stock and barrel—by our founder, Lycurgus, centuries and centuries ago. But if you look at Lycurgus from the point of view of legal history, you’ll see things differently. Using evolutionary models, we understand the Spartan oral tradition as representing a set of customary laws that developed organically over the years. We can move back in time to suggest the nature of the law 100 years, 200 years, maybe even 300 years earlier. No fifth-century B.C.E. Spartan would say, “Oh yes, the Cosmos took centuries to evolve into the very efficient body of law we have today.” He’d say, “The Cosmos was the creation of the genius law-giver Lycurgus, who presented it to us in all its perfection. Our duty is to keep it perfect and maintain it, and that’s why we meet every year on the days of Lycurgus and reaffirm its perfection.” Oral traditions tend to think of the here and now as perfect, as a gift of the culture-hero from time immemorial.

JM: Plato calls Homer “the poet.” He claims Homer is superior to all other poets—and therefore, of course, he kicks Homer out of the Republic.

GN: Yes, Homer is the big threat, along with tragedy.

JM: Did Plato have a written text of Homer’s poems?

GN: He probably had a written text, but that’s sort of secondary—like having a transcript of something you know by heart.

JM: You think Plato knew the poems by heart?

GN: I’m pretty sure he did. Plato himself suggests that he did in his dialogues, especially in Hippias Minor and Ion. Let’s take an example from Ion, in which Plato’s Socrates has a battle of wits with the rhapsode (oral poet) Ion. In Plato’s day, the word rhapsode designated a professional performer of Homer’s poetry. Socrates asks Ion, “Now what does old man Nestor say to young Antilochus about how to make a left turn in a chariot?” You can imagine Ion’s mind fast-forwarding to Scroll [Book] 23 of the Iliad, where Nestor is speaking to Antilochus, and he starts reciting the passage, continuing on and on. Socrates has to say, “OK! That’s enough!” If not, Ion would have kept going right to the end. Socrates then shows that he can do Ion one better, that he can jump around from later to earlier Homeric passages. He can fast-forward and rewind.

SB: You seem to be saying that Homer is really the Homeric poems themselves.

GN: He’s the incarnation, the embodiment of Homeric poems as they are received. In that sense, Homer is a real historical entity.

JM: He just evolved?

GN: Yes, and the more he evolved, the more he was admired.

JM: In calling yourself an “evolutionist,” you mean that the Iliad and Odyssey developed over time. We start with a diverse group of myths in an oral tradition, which can absorb just about anything, and we end up with texts that are pretty much frozen.

GN: Yes. My evolutionary model takes us from fluid to rigid. I start around 1500 or 1400 B.C.E. and go forward in time.

JM: Do you start there because that’s the Mycenaean period?

GN: I start there because that’s where we start having historically or archaeologically verifiable details preserved in the poems.

JM: You’ve already mentioned the chariots. How about another example?

GN: My old friend and colleague Emily Vermeule was convinced that the horsehair helmet Hector wears in Book 6 of the Iliad, when he embraces his infant child for the last time, has to be dated around 1400 B.C.E.

JM: Because of the archaeological record?

GN: That kind of horsehair helmet went out of production after a certain point. No kid living after the 14th century would ever again be frightened by a horsehair helmet. This is another illustration of how myth reorganizes historical detail without annihilating its historicity. At this heartbreaking moment, the poem combines eternal human emotions—a father saying goodbye to his infant son—with a specific historical detail, the horsehair helmet, dating to the Mycenaean period.

JM: The first phase of your evolutionary model, which lasts until the eighth century B.C.E., is purely oral—that is, Homer’s poems were being transmitted by being recited, not by being written down. But the oral tradition is developing in some way.

GN: Yes.

JM: Is this development rule-governed?

GN: Yes, decidedly so. Your judicious phrase “rule-governed” gives me an opportunity to mention Milman Parry. [Harvard scholar Milman Parry’s important work on oral poetry did not become well known until long after his death in 1935. Much of his work was originally written in French and was not published in English until 1971.] Parry showed that we can identify the remnants of three different dialects in Homer’s epics, and these dialects can be dated relative to one another. So it’s like archaeology. The earliest one is what Parry and his contemporaries called Arcado-Cypriot; today we would call it Late Bronze Age Mycenaean Greek. The next layer, as far as Parry could reconstruct it, is the Aeolic dialect as it existed around the ninth and tenth centuries B.C.E. This dialect is attested many years later in the poetic language of Sappho [who flourished, according to the traditional dating, around 600 B.C.E.]. And the third and most prevalent layer is the Ionic dialect. I have called these three Homeric layers the “dominant” for the Ionic, “recessive” for the Aeolic and “residual” for the Arcado-Cypriot or Mycenaean. As the terms suggest, in the Homeric text there’s a lot of the dominant Ionic linguistic stratum, less of the recessive Aeolic, and a great deal less of the residual Mycenaean. Parry essentially said that if your current dialect, whatever it is, has a way of saying something already expressed in an earlier antiquated layer, then you will replace it—just an automatic substitution. But if you can’t update it, and keep it within the meter, then you’re stuck with the earlier material.

JM: If you can say it better, then you say it better. But if you can’t improve on it, you leave it alone.

GN: If it’s really good, you retain it, even though it sticks out like a sore thumb.

JM: There’s a passage in the Hebrew Bible, in the First Book of Samuel, in which the Israelites are described as taking their weapons to the Philistines for repairs [1 Samuel 13:19–21]. The meaning of one of the words in that passage, pim, was lost over time. Nonetheless, it remained in the text.

GN: Yes, the sore thumb.

JM: In the various English editions of the Bible, pim is translated in different ways. The King James Version renders it as “file,” suggesting that the Israelites brought their bronze swords to the Philistines, who kept a monopoly on iron, to be sharpened with an iron file. But now we know better. Modern excavations have turned up a number of small half-shekel weights with the word pim incised on them. So it now appears that a pim was the price the Philistines charged for their services.

Incidentally, these pim weights help date the text. They are found only in ninth- to seventh-century B.C.E. contexts. In the Persian or Hellenistic periods [fifth century to early second century B.C.E.], to which some scholars date the text, no one would have known what a pim weight was. Like the horsehair helmet.

GN: Oh, that’s a most elegant analogy.

SB: Milman Parry was not the first to suggest that the material that came to form the Iliad and Odyssey began as part of an oral tradition, was he?

GN: No, the idea that Homeric poetry was originally a collection of oral stories goes back to the likes of Friedrich August Wolf (in his Prolegomena ad Homerum [1795]) and even Jean Baptiste Gaspard d’Ansse de Villoison, who in many ways anticipates Wolf in his 1788 edition of the Venetus A manuscript of Homer. When Parry wrote his doctoral theses at the University of Paris in 1928, he didn’t even use the word “oral.” He had no experience in fieldwork. One of his professors—Antoine Meillet—suggested that he study the living traditions of oral poetry. So after he took a position as assistant professor of classics at Harvard, he decided to go to the Soviet Union to continue the work of Wilhelm Radloff, who had studied Turkic oral composition techniques in the late 1800s. When Parry was unable to get a visa to study in the Soviet Union, he decided to go to Yugoslavia instead. So in 1933 Parry began studying oral epic poetry in the Balkans, with his student Albert Lord—who later wrote the extremely important work Singer of Tales [1960].

JM: Lord was also your teacher.

GN: Yes, and I consider myself to be in the Parry-Lord tradition. Parry and Lord built an empirical system to die for, considering that the collection of oral traditions in those days was still in its infancy. Their intention was simply to try to find out what a living oral tradition is like. Only after that did Parry begin using the phrase “oral poetry.”

Essentially Parry and Lord showed that oral poetry can be highly systematic and cohesive. Moreover, the composition of an oral poem is subject to renewal with each new performance, in that composition and performance are aspects of one creative process. Oral poetry is a language in its own right, with its own grammar, and this language transcends ordinary language in its complexity and its precision.

But what Parry and Lord discovered in the living oral poetic traditions of the South Slavic song culture could only be applied elsewhere as a model, a typological parallel. Lord was very clear about this. He did not ask whether South Slavic oral poetry is actually related to anything else. He thought it possible that some singer dictated the text of the Iliad and the Odyssey to a scribe around the middle of the eighth century B.C.E. I, for my part, do not accept the dictation hypothesis. To be fair to Lord, however, the dictation model was just a model; he couldn’t imagine why anyone would bother to write the material down—in an ancient Greek context. The only historical speculation Lord did indulge in was to say, in Singer of Tales, that there must have been cultural contact between the Near East and the evolving oral tradition of Homeric poetry. He specifies Nineveh, of all places.

SB: Since ancient times Homer has been associated with the East, with Ionia and the Anatolian coast.

GN: Definitely, there are eastern influences. The question is how. In his ambitious book The East Face of Helicon, Martin West goes too far in saying that there must have been a kind of hotline between places like the library at Nineveh and the poet of the Iliad, as he calls Homer. Still, I subscribe to Lord’s idea of some degree of cultural contact between Greek practitioners of poetry and their Near Eastern counterparts. You have to imagine, say, classes of artisans traveling from principality to principality, from land to land—artisans of various origins. They would have been linguistically and culturally bilingual or trilingual, and they would have carried ideas, languages, forms of art in all directions.

JM: This kind of cultural contact is characteristic of the so-called Dark Age of the first quarter of the first millennium?

GN: Yes, absolutely.

JM: If these highly civilized, multilingual Greeks were traveling throughout the eastern Mediterranean, why is there no writing for a few hundred years?

GN: Oh, that! [Laughs]

JM: We don’t find any mention of writing in Homer, except for the “folding tablet” inscribed with “murderous symbols” in the story about Bellerophon. This is different from what we find in the Near East. After conquering an enemy, your typical Assyrian king would erect a victory stela with an inscription, saying something like “I overwhelmed the enemy like a snowstorm!”

GN: Well, I think I’ll surprise you. In my book Homeric Questions [1996], I actually leave the door open for a lot more references to writing, even in Homer. My favorite example is when Hector imagines what will happen after he defeats the greatest of the Achaean warriors in battle; Hector says they will lay a grave marker for the fallen hero, and then he “quotes” what people will say (Iliad 7.89-90). His quoted words are in the language of inscriptions, poetic inscriptions that memorialize the dead, from the seventh century and thereabouts.

JM: There are Greek inscriptions, in good hexameter, from the eighth century, but not earlier. The Dipylon jug, the Mantiklos inscription.

GN: You’re worried that before the eighth century, when the Phoenicians have forms of writing, it looks as if the Greeks don’t have anything?

JM: Not only the Phoenicians, but also the Hittites, Mesopotamians and Egyptians. There’s a tremendous history of myth being recorded, as well as diplomatic letters being exchanged between kingdoms. This is a tradition going back more than a thousand years.

GN: Yes, yes. I don’t rule out the possibility that Greek civilization had writing earlier. I’m not one of those people who say that if there’s an oral tradition, there can’t be writing, or vice versa. I don’t see literacy and oral tradition as mutually exclusive. I’ve studied too many examples where you see them happily coexisting.

JM: So the oral tradition keeps evolving, even as writing becomes widespread.

GN: Yes, I think so. I don’t think writing had much to do with the development of the Homeric material, not until the very end.

SB: How did the Iliad and Odyssey get written down?

GN: This goes back to my five stages of the evolution of Homeric poetics.

JM: We’ve almost gotten to the end of the first stage! [Laughs]

GN: By the fifth century B.C.E., only the Iliad and the Odyssey were performed at the Panathenaea [the principal religious festival of Athens, honoring the city’s tutelary goddess, Athena], and Homer was thought to be the poet who created these poems. Earlier, however, the Iliad and Odyssey were part of a larger epic cycle of poems. Remember, for example, that the Iliad begins in the tenth year of a ten-year war, so there once were stories about how the war begins and is prosecuted. Remember, too, that the Iliad ends with the funeral of Hector—the war isn’t even over yet. So there is also material covering what happens between the Iliad and the Odyssey. There was a lot of material that just didn’t make the final cut. In the classical period, when the epic cycle became streamlined into the Iliad and Odyssey, the other stories were simply thought of as non-Homer. As you move forward in time, the Homeric material comes under the control of the Athenian empire. Now the Athenians own Homer, not the Ionians or Aeolians or Mycenaeans. By the fifth century B.C.E. you have something very close to what you and I know as the Iliad and the Odyssey.

JM: Are the poems still evolving in the fifth century?

GN: They’re still evolving, but at this point the pace really slows down.

JM: Then let me ask a specific question. Did the playwright Aeschylus (c. 525–456 B.C.E.) know Homer?

GN: I think he had it hardwired in his head, though his Homer was probably in some ways different from ours.

JM: In the Oresteia, Aeschylus’s trilogy of plays, Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia to appease the gods. Agamemnon’s wife Clytemnestra then conspires to kill her husband when he returns from Troy, because she is angry over the killing of her daughter. But this story does not appear in Homer, despite the fact that the murder of Agamemnon is recounted again and again in the Odyssey. If the Homeric epics were still evolving, still adding and subtracting stories, why not include the story Aeschylus knew, that Agamemnon sacrificed Iphigenia to the gods? It would supply a good motive for his wife’s taking revenge.

GN: The Iphigenia story is one of many stories that didn’t make it into the final version of Homer. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t known at an early date. Moreover, at the beginning of the Iliad, we are given a sense of how Agamemnon treats his wife when he claims Achilles’s girl-prize, Briseis, as his own—thus incurring Achilles’s wrath and setting the whole poem in motion.

JM: Agamemnon says, “I need a girl, and these girls are prettier than my wife at home!”

GN: Then, to appease Achilles, Agamemnon offers his three daughters as potential brides for Achilles. He says, “Take any one of them—X, Y or Z.” No mention of Iphigenia, whom we are expecting in slot “Z,” but there is a “placeholder.” The third daughter is called Iphianassa (Iliad 9.145, 287), a name that is a metrical and formulaic “twin” of Iphigenia. It’s as if the poet were saying, “I know the tradition that the sacrifice of Iphigenia causes a rift between Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, but I’m going to use another one. And my story also involves a kind of sacrifice.”

When things were fluid like this, when rhapsodes still had the power to recompose while they performed, you would have the most fantastic, flamboyant epic performances. For much of the sixth century, Athens was ruled by a family of tyrants called the Pisistratid Dynasty [c. 561–511 B.C.E.], who tried, with varying success, to manipulate the performances at the Panathenaea festivals. When the tyrants were overthrown and Athenian democracy began, there was a stronger sense of civic learning through poetry—and then, boy, things really got streamlined.

So in my five-stage model you have, first, a long period in which an amorphous collection of oral poems coalesces into a coherent cycle of poems, and then you have a period in which this cycle of poems gets streamlined and regularized. The last three stages I call the transcript, script and scripture phases. In the transcript stage—fifth-century B.C.E. Athens—you want your kids to become educated by committing Homer to memory, particularly Homer as performed by the rhapsodes at the festival of the Panathenaea. This is the transcript phase; then, comes the script phase.

JM: “Script” meaning what?

GN: You go by the book. The poems are fixed, and people would get really agitated when the poems were tweaked from one Panathenaea to the next. So they would try to control the performances; not only was the broader cycle pared down to the Iliad and the Odyssey, but these epics were to be recited only in a certain way.

SB: This reminds me of an example from music. When Mozart would perform his piano concertos, he’d improvise the cadenzas. Over time, however, the cadenzas were written down, and today they’re fixed.

GN: Yes. Statesmen began doing that kind of thing with tragedy as well. Things became really rigid in the fourth century B.C.E., when the Athenian state declared that there were only three official tragedians and that only their dramas would be in the state archives. If you were planning to perform Homer, too, you had to do it exactly right.

JM: You don’t mean writing, do you? You mean that the poems are fixed, whether written down or not.

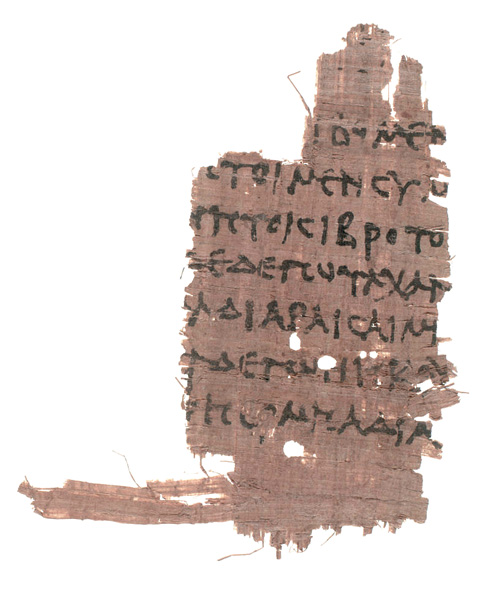

GN: No. They’re fixed, scripted; writing doesn’t matter. If you make one slip, people will know. That’s the script phase. The next phase comes toward the end of the fourth century B.C.E., with the weakening of the Athenian state. In this period, the state of Athens could no longer control how Homer was performed at Panathenaea festivals. So the rhapsodes went wild. Everybody was trying to recover as much variation in the poems as possible. At about the same time, however, scholars at the Alexandria Library began trying to reconstruct the real Homer.d And the way to reconstruct the real Homer was to go back to earlier written transcripts. Now writing mattered enormously. This is the scripture phase—when scholars strove to produce authentic, divinely inspired versions of the Iliad and the Odyssey. One of the Alexandria Library scholars, Aristarchus of Samothrace (c. 217–145 B.C.E.), finally nailed it down.

JM: Now the story is pretty much over.

GN: Yeah. We’ve completed the journey from fluid to solid.

JM: I can’t let you go without asking, Why should we read Homer? What’s special about these epics?

GN: It’s a distillation of human life, like a wonderful cognac.

JM: The endless possibilities of human life—suffering, heroism, tenderness …

GN: Yes, everything. Being able to empathize with somebody you hate more than anyone in the world. The idea that somebody like that can make you cry with compassion is an example of poetry soaring to the heights of humanism. Homeric poetry also explores the depths of brutality and even bestiality—which is a wonder to me. The cultures of the ancient Near East and Greece shared this fascination with the beast. Homeric poetry tests all facets of humanity; it’s a never-ending search for points of contact, points of agreement, where people who disagree about everything else are in tune, emotionally or intellectually.

That’s an odyssey—traveling from place to place and discovering that every locale has its own mode of being. The traveler discovers an expanded way of thinking, an expanded way even to think about thinking. So Homeric poetry is a beautiful vision of diversity, something we hunger for at the beginning of the third millennium C.E.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Tzvi Abusch, “Gilgamesh: Hero, King, God and Striving Man,” Archaeology Odyssey, July/August 2000.

See H. Kenneth Sams, “King Midas: From Myth to Reality,” Archaeology Odyssey, November/December 2001.

See the following articles in Archaeology Odyssey, Premiere Issue 1998: Birgit Brandau, “Can Archaeology Discover Homer’s Troy?”; Carol G. Thomas, “Searching for the Historical Homer”; and Jasper Griffin, “Reading Homer After 2,800 Years.” See also the following articles in Archaeology Odyssey, July/August 2002: Rüdiger Heimlich, “The New Trojan Wars”; and “Greeks vs. Hittites: Why Troy Is Troy and the Trojan War Is Real” (interview with archaeologist Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier).

See J. Harold Ellens, “The Destruction of the Great Library at Alexandria,” Archaeology Odyssey July/August 2003.