The book of Job, one of the world’s greatest literary works, is better known for the problems it poses and the issues it spawns than for its answers and resolutions.

While to the untutored eye, Job (at least in translation) reads smoothly from the beginning to end and exhibits cohesion amid diversities, more critical investigation uncovers seams in the fabric if not rents. There are rough passages and rougher transitions. A good case can be made that various segments are intrusive and were not part of the original work. Other questions have been raised about the sequence of speeches and their integrity and completeness.

Nevertheless, we must also respect the final editor or compiler of the book. It is not an accidental assemblage of disparate and disconnected materials. Whatever the ultimate origin of the several parts, they have been worked into a whole, and if seams and gaps are still visible, then Job is hardly different from other great works of literature and art. It is reasonable and legitimate to deal with the book as a whole.

The book does have an overall unity, including all the parts. It is the story of an upright, God- fearing man—Job of the land of Uz—who endures terrible suffering, but who nevertheless perseveres in his integrity and fidelity, and is ultimately rewarded for his faith by being restored to his former estate and compensated for his losses, pain, and suffering.

From the start it is established that Job is virtuous and righteous (1:1). This is the premise of the book. Any valid interpretation of the book must accept this premise.

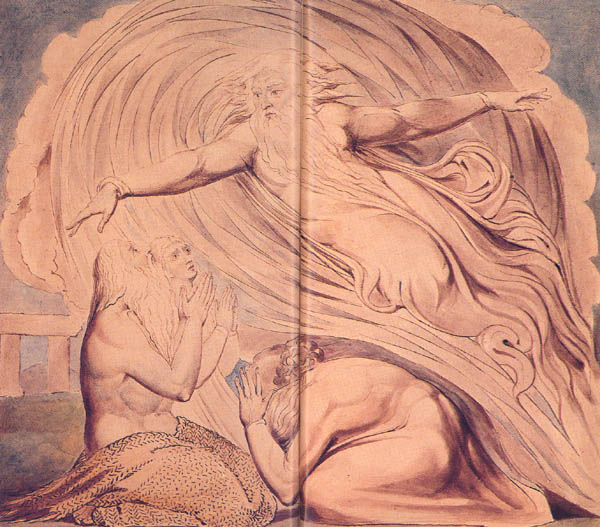

Enter now the Adversary or the Satan (ha-satan, in Hebrew), who reacts to Yahweh’s assertion that there is no one on earth like Job, “a blameless and upright man who fears God and shuns evil” (1:8). Satan responds that Job’s righteousness is not a matter of pure and undiluted faith, but rather is a calculated piety rooted in the relationship between God and Job. In other words, God cannot claim that Job serves and reveres God for the latter’s self alone, which is the true test of faith and faithfulness, but rather Job is responding to the care, protection and prosperity that God has provided for him. It is a very good deal for both parties, suggests Satan, but it by no means establishes that Job is inwardly righteous, only that he knows how to respond to divine grace and thereby reap a rich and continuing reward. In so doing, Satan argues, Job has successfully hoodwinked the deity, who has fooled himself as well into thinking that Job is objectively just and disinterestedly righteous. According to Satan, nothing could be further from the truth. If God would only take away from Job what he has given him in the way of material possessions and blessings, he would quickly discover what Job really thinks of him, and how thin and superficial Job’s piety and righteousness in fact are.

God is intrigued by the proposal, and since he is convinced that Job is truly faithful and righteous—namely that he reveres God for himself alone and that Job will adhere to him regardless of personal fortunes—God permits Satan to carry out his proposal.

Satan inflicts a series of devastating and destructive blows on Job’s possessions, including not only his material goods, but his servants and children as well (only his wife is spared, an interesting point, but not discussed in the story).

No one ever questions that in fact it is God who is responsible for what happens to Job. Just as Job’s righteousness is a given, so is Yahweh’s ultimate responsibility for what transpires. It is clear that Satan acts only as agent. True, it was his idea, and Yahweh only granted him permission to proceed, but in the end that doesn’t matter. Satan operates as a kind of prosecuting attorney of the divine court. Satan is part of the divine entourage and serves God as prosecutor of humans who have broken the divine rules and regulations. In the case of Job, it is clear that Satan has no valid charge to bring against that holy and upright man. But he invents one nevertheless and thereby raises a serious theological question for which there is no easy or simple answer.

When Satan takes away Job’s material possessions and blessings, Job does not break; Satan remains unsatisfied, however, that Job’s behavior has vindicated Yahweh’s position. Satan contends that the test thus far has been insufficient and that Job himself must be attacked. That is the test. Then, according to Satan, Job will abandon his faith and his integrity, and curse God openly, thereby vindicating Satan’s view against God’s. God accepts the possibility that Satan may be right. So it happens that Satan, armed with divine permission, inflicts some terrible disease on Job, with the result that Job must finally feel that he has been abandoned by God. Even in that dire strait, he refuses to reject the God who may have rejected him, or to utter the blasphemy that might be regarded as appropriate or understandable under the circumstances.

At this point, the heavenly debate is suspended while the drama continues on earth. Job goes outside the village to suffer in solitude. He is joined by three companions—Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar—, and then a lengthy dialogue ensues about Job’s condition, physical and spiritual.

The Dialogue fills the gap between the conclusion of the second test imposed on Job and his restoration and reward at the end of the story. It is the bridge between the Prologue (1:1–2:10) and the Epilogue (42:7–19). Once Satan imposes the second test—a severe inflammation on Job’s body, from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head—he plays no further visible role in the story. He simply drops from sight.

The huge Dialogue (95% of the book) poses a structural problem. The best way to deal with it is to recognize it as a continuation of the testing. In short, it is a third test. Whatever the friends may have intended by coming to condole with Job, the actual visit and subsequent conversation turn out to be part of the testing process, perhaps even more trying to the upright Job than his previous suffering as Satan’s victim. While nothing is said explicitly, we may conclude that the friends and especially their arguments constitute a third effort on Satan’s part to bring Job down.

The friends argue in essence that Job should concede the main point, that he must have been guilty of some breach of the compact with God, and that even if he can’t identify it he should confess, repent, be forgiven and restored, and that would end the matter. In other words, repentance is a panacea and universal solvent; even in unclear cases, it is better to repent than to be stubborn and compound the original sin by challenging God and in effect attack him by a form of self-justification. This sounds reasonable enough, but in fact would play into Satan’s hands and achieve his objective. Job in so doing would seek cheap grace at the price of his innocence and integrity. The premise of the whole book is that Job is honorable and innocent, a good, just man. That is the given; it is assented to even by Satan. For Job to throw in the towel would prove Satan right and God wrong about Job. Hence the strong anger God expresses in the end about the friends (42:7–9) who are nothing more than agents of Satan in trying to get Job to compromise his integrity.

Job withstands the friends in three cycles of speeches and replies. Each of the three cycles consists of speeches by Job’s friends and Job’s responses.1

No ground is gained or lost in these speeches, except that the original friendships are badly frayed by the end of the third round. The futility of debate except to strengthen one’s own resolve has never been more dramatically demonstrated.

Interestingly enough, the three friends never speak to one another; they never question each other or discuss strategy or goals. Their only interaction is with Job who himself is entirely impartial, responding in the same vein and spirit to each of them. In the end, as the dialogue winds down, the speeches become shorter and the orderly sequence seems to wobble and then fragment and fall apart as though they had finally worn themselves out. The effect is to raise the level of dramatic fury, thus focusing all attention on the beleaguered Job to whom the friends address all their remarks.

There follows a digressive allocution on the subject of wisdom (chapter 28), not addressed to anyone in particular but clearly aimed at the reader—a kind of intermezzo on wisdom’s scarcity and extraordinary value, as though to advise the reader that the preliminaries are now over. The main issues are going to come and will require the most serious exercise of that prized faculty, namely wisdom, in order to grasp the points at issue and the proposed resolutions. Although this digression (chapter 28) may appear to be part of Job’s last speech in response to his three friends, it is in fact an independent composition.

Job’s final speech (chapters 29–31) is an explicit and detailed affirmation of the original premise: Job is an upright person whose manner of life always met with divine favor until the sudden and inexplicable change in God’s behavior. Job remains adamant that the problem is with God, not with him. And so at the end of the discourse between Job and the three friends, the third failure to budge Job from his integrity is recorded. It is instructive that the issue throughout is Job’s insistence on his innocence and righteousness, which is precisely the core of the conflict between God and Satan

Soon Yahweh himself will re-enter the drama. But first a fourth friend appears on the scene, previously unannounced and unaccounted for. He is Elihu, a comparative youngster, brash at that who speaks to and at everybody criticizing the friends for inferior debating, but at the same time attacking Job for his behavior. He argues vigorously, brooking neither interruption nor rejoinder. After four consecutive speeches filling six chapters (chapters 32–37), he finally stops. The fact that neither Job nor his friends respond in any way suggests that all contact among the human parties has now ended and that Elihu is speaking for the record and possibly the reader. The alienation of man from man has reached an ultimate point. They are all talking, but no one is responding, probably because they are no longer listening.

While Elihu is highly critical of all who have preceded him and very scornful in his excessively polite and prolix fashion, he does not add much to the sum of human knowledge. In spite of his insistence on being heard, and his rapid fire, nonstop loquaciousness, he earns an ultimate reward: He is totally ignored, not only by those whom addresses but by the Almighty as well. I believe that Elihu—who comes from nowhere and disappears from the scene as soon as he is done with his speeches—is not a real person at all. Like the other participants, he has a name and a profession, but it is a disguise—as is so often the case in Greek epic. He is the person assumed or adopted by Satan to press his case for the last time.2 His speeches are Job’s fourth test. Because Satan through Elihu has taken a personal hand and a very threatening one, God feels that he too must intervene. Hence the next and last speech is that of Yahweh himself. He cannot risk Job’s replying to Elihu because Job may be at the point of resignation and repudiation. So God makes his own reply to settle the wager and all its associated issues.

Nevertheless, just as Satan is tied by the rules, so too is Yahweh. He is constrained by the compact not to offer Job consolation or encouragement. If he did, this would produce the same situation that Satan complained about originally and would muddy the waters. For the test to be a true one, Yahweh has to stay out of it. But being totally out of the picture doesn’t seem fair either. He can make a statement. Beginning in chapter 38, Yahweh speaks to the group, but addresses Job in particular, in a two-part speech of great power and brilliance. Here at last Job has a worthy antagonist, and as Job himself concedes, he has at last met his match—indeed is overmatched. God’s first speech (chapters 38–39) is followed by the briefest of responses. Says Job:

“See, I am of small worth; what can I answer You? I clap my hand to my mouth. I have spoken once, and will not reply; Twice, and will do so no more” (40:3–5).

Yahweh then launches into a second major address (chapters 40–41). Job in turn makes a final response, in which he confesses his fault—failure to understand, lack of wisdom and knowledge. Job repents on dust and ashes (chapters 42:1–6).

Yahweh’s seen speeches hardly deal with Job’s complaints and grievances. Yet, genuine dialogue is established, and Job is content with the fact that Yahweh, while basically professing to be thoroughly occupied with responsibility for running the universe and with some of its more impressive and spectacular inhabitants, and therefore too busy to care about or intervene in the petty affairs of human beings, nevertheless has responded to the urgent appeals of Job. Moreover, by responding he has demonstrated that, excessively busy or not, he is aware of the human predicament and can and does intervene when there is a compelling reason to do so. In short, God is too busy with other important matters to pay much attention to humans, and hence Job should not make such a fuss because things have gone wrong.

Job is abashed by the divine intervention and ashamed of his own prior complaints about his plight. Actually, Yahweh’s speeches are not very helpful, as most scholars have observed; moreover, if this is the author’s point, then he is at odds with most of the rest of the Bible, which reflects God’s intimate concern and attention to what people do.

But the editor of the book has a different strategy. This is all that Yahweh can allow himself to say since, otherwise, he would violate the terms of the wager. Just as Satan may not finally kill Job, so God is not allowed to reassure Job about his positive and supportive interest in this frail human being. That would completely spoil the test. But Job gets the right message even from the wrong words. What God denies in his words is affirmed by the fact of his speaking. Job understands that Yahweh’s blast from heaven is nevertheless the very word that Job needs—to know that Yahweh has his eye on him and has expressed his concern for him. That is enough; Job responds, “With the hearing of the ear I had heard you. But now my eyes have seen you” (42:5). Now he knows that God does care for him and he can freely repent and thus pave the way for the conclusion of the book—his restoration and reward. Thus both Satan and God have pressed their case upon Job, who finally makes the necessary move to end the struggle between the opposing forces.

Job withdraws his grievance and charges. He has finally done what the friends had insisted on arrogantly and insultingly from the beginning, to repent on dust and ashes: “Therefore, I recant and relent” (42:6). The way is thus cleared for the final resolution of the predicament in which Job has been placed. God judges that Job has vindicated the deity’s faith in him, and therefore Job can be restored and compensated for his suffering.

Yahweh clearly and cheerfully concedes that Job has been wronged and that he has a just cause and claim against the deity. This concession is implicitly confirmed by the compensation over and above simple restoration: Job receives double his former possessions, which is one of the specified damage awards for the victim of unjust confiscation of property. In addition, Job’s children are also restored. The miracle confirms the potent goodness of the patriarch and the surpassing grace of the deity. In the end, everything is as it was, only better.

The story of Job begins on the ragged edge of heresy and lurches and sags in a variety of directions increasingly distant from the central biblical tradition, which is characterized by absolutes and historical certainties and commitments.

The drama is two-fold. One scene is played out on earth with the unfortunate Job and his household (or what is left of it—only his wife), providing the framework for the dialogue. The other scene is played out in heaven by an entirely different cast of characters, including an all-powerful and willful deity, surrounded by servitors. Not merely echoes or sycophants of the Almighty, they are intelligent, serious and significant actors whose participation in heavenly decision-making is positively alarming.

These two stories intertwine and produce palpable effects on one another, but the levels are separated, as it were, by a tinted glass that permits vision and knowledge in one direction only. The heavenly participants alone know what is happening to whom and why, while the earthly counterparts wander in a vast confusion, their confident assumptions and assertions playing against the contrary realities revealed in the heavenly scenes. The reader is carefully positioned by the author/editor so as to be fully aware of both scenes and of the calculated ironies and paradoxes.

Suspense builds as the audience, within and without the story, wonders not only what will happen to Job and his interlocutors, but whether any of them will ever find out the real inner truth. Will they unwind the onion to its core, or will they in the end have to be content with conventional wisdom, pious platitudes, and the pervasive subterfuge that dominates the dealings of the heavenly sphere with, that of humans.

As it turns out, the issues are resolved only at the level at which they began: Job, the innocent and righteous sufferer through no fault of his own, is restored to health and happiness and recovers his family and his fortune. But he is no wiser than he was before. His testing has satisfied his testers, and he passes with flying colors and great rewards. But he may well be more perplexed than satisfied, more disturbed than complacent—and certainly ignorant of the true workings of the heavenly court.

Paradoxically, until the resolution, even God does not know how matters will turn out, since at the heart of the story is the question of Job’s integrity: Will he stand fast or will he succumb to the inexorable pressures of his undeserved suffering and finally to the temptation to curse his Maker? If there is uncertainty for God, how much more so for the other actors, especially the human ones, who are never privy to the central secret of the drama: the wager or test between God and Satan. If Job, ignorant of the truth, is deeply disturbed and badly upset by the course of events, how would he behave if he had some real inkling of the truth?

From one perspective, the issue is the test of Job’s integrity and faithfulness. From the viewpoint of someone on earth, however, it looks very different. From that viewpoint, it is a test of God’s righteousness and faithfulness. Is there a moral law of the universe, does God have any ethical integrity, or is the universe run in a totally amoral fashion? The reader is shown two very different sides of the same human situation, and perhaps the intention was not to resolve issues but to explore and exploit them. The explanation and solution offered in the Prologue and Epilogue suffice to provide a framework and a way of starting and stopping, but long after the fate of Job himself is resolved, the issues raised in the Dialogue persist, and the speeches of all the participants reflect and express deep concern about the fundamental religious issues of all times: the nature of God and his relationship to the created universe; the plight or position of humanity in relation to God and his world; the problem of suffering; and the responsibility and obligation of humans toward God and toward each other.

Finally, the question must be raised about the issue between God and Satan. Why did God accept Satan’s challenge about Job’s righteousness? Satan questioned Job’s integrity and sincerity. Jobs devotion and dedication, according to Satan, were merely a device to gain and maintain Yahweh’s blessing. Satan is confident that if Job’s faithfuless is tested, he will break under pressure, and the malign truth about his inner feelings will be revealed. True, Satan can’t know this in advance, and ultimately he is proved wrong. But what about God? Doesn’t he know? Doesn’t he know everything in advance, especially what goes on inside a man’s heart and mind? It is axiomatic in both Christianity and Judaism that God is omniscient, omnipotent and has a monopoly on all the other attributes reflecting his absolute divinity. So how can there be any question as to whether he knows in advance or whether he is entering into the test in good faith?

There are actually two problems here. If God knows everything and in particular that Job is truly faithful, as God avers, then why should he allow Job’s faithfulness to be tested? First of all, it is a terrible thing to subject Job to all these trials, tribulations and outright suffering, especially when there is no point to it, except perhaps to show up Satan and his false pretensions. But, secondly, it isn’t fair to Satan either. If God knows it is a sure thing, then he shouldn’t enter into a wager with Satan.

The truth, however, is that despite theological claims about divine omniscience, and assumptions by most believers, the God of the Hebrew Bible is not omniscient, although he certainly has a great deal of knowledge about most things that count. There is, apparently, a self-imposed limitation when it comes to the inner workings of the human soul. To determine finally what makes human beings decide ultimate questions and offer ultimate commitments requires scrutiny and testing. Several examples in the Bible demonstrate this need for testing. The greatest exegetes have attempted to show that the story in Genesis 22 of Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac does not imply any limitation in God’s Knowledge of Abraham’s fidelity. Yet, the story clearly says otherwise: The purpose of the test when God calls on Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac (as it is explicitly stated in Genesis 22:1) is so that God can determine whether Abraham is Willing to obey the divine command to surrender his only son, whom he loved, to God’s demand for such a sacrifice. The implication is clearly that God imposed the test in order to find out something he did not know before. Moreover, in Genesis 22:11–12, after Abraham passes the test, God says, “Now I know …”

The same limitation on God’s knowledge is reflected in Deuteronomy 8:2–3, where God explains that he kept the Israelites in the wilderness for 40 years to test them (among other things), to find out what was in their hearts, whether they would prove faithful or false.

The same is true in the test of Job. The test is imposed so that God as well as the Satan can find out whose contention about Job is correct. Is he faithful to God for God’s sake or for his own? The essential determination cannot be made without testing. God might have created human beings differently, so that they could be known and understood without testing, but it was essential to his purpose that human beings be responsible for their decisions and actions, and be answerable for what they decide and what they do. They must be free of divine control and foreknowledge. Although it is highly debated in both Judaism and Christianity, the evidence in the Hebrew Bible points to a mystery at the center of the human person, a mystery that even God respects, so that the ultimate truth of human commitment can only be decided by time and testing.

It may seem a curious paradox, but within the story of Job, God cannot proceed with the test in fact he knows the answer conclusively beforehand. He can have the same or opposite confidence that Satan has—that is what makes for a challenge and a legitimate wager. But he must be able to be proved wrong. If he proceeds with the test, that proves that he doesn’t know in advance.

The argument propounded by Job’s three friends—they are in essential agreement on the a main points—is that it is sacrilegious to even hint at, much less utter that God is not just in his dealings with the world and with humanity. From that premise, the friends argue back to the palpable inference about Job’s suffering: Since it is axiomatic that God is the source of bane as well as blessing, and since God is by elemental definition just in his dealings, it follows that Job has done something, or said something, or thought something contrary to the law of God. And, according to his friends, he only makes things worse by stubbornly insisting on his righteousness. There is a solution to the dilemma, they say, and that is to repent If Job will concede that the root of the trouble lies in his stubborn unwillingness to confess his faults, and make amends and truly repent, then the friends are confident that the present agonies will cease and Job will be restored to divine favor, with all the appropriate restitutions and recompenses.

Job does not receive either the analysis of what ails him or the prescription for resolving the issue and solving his problem. He cannot repent and seek forgiveness for sins and crimes that were never committed. Which has been done to Job and is being done is intended to be outrageous. Satan makes sure that the experience is so unbearable that Job will ultimately curse God—even as his wife so strongly recommends (she presumably is not taken from Job along with the rest of his family because she serves, like the friends, as an agent provocateur—carrying out Satan’s purpose to push Job into the final stage of disillusionment and frustration and thus into cursing God).

The friends’ argument is impeccably drawn from a premise that is undoubtedly correct and central to biblical religion. The God who created an orderly universe and made laws by which it is run cannot himself violate those laws and act unjustly toward upright human beings, themselves upholders of his law. If Job is being treated badly by the deity, the latter must have adequate evidence against Job in order to justify the treatment receive. Hence, Job must be guilty of some grave offense, and his denial of that well-nigh certain inference only compounds the original crime and makes the punishment more certain and more severe.

Job rejects the inference, the argument, and ultimately, at least in a sense, the central premise. His starting point is his own innocence. On this he will not budge, and in fact this is central and crucial to the whole argument. The reader is forewarned by the author-editor from the very beginning of the story that Job’s righteousness is not to be questioned. This is the primary given of the story: Divine, satanic and human views converge and agree on this point Job is an honest, honorable man whose integrity is vouched for by God, Satan and Job himself.

Job’s conclusion about his doleful experience, and he derives it from his own integrity, is that God is unjust in his dealings. Everything that has happened to him is acknowledged by all to be the result of deliberate decisions and executive actions by God. Job’s inference is that, since his sufferings are incompatible with his merits, it is clear that the proper system of rewards and punishments has broken down and that God is in violation of his own code of ethics. In short, God had no right to punish Job, and hence his friends are wrong.

Job’s argument from premise to conclusion is just as impeccable as that of the friends. If the premises are accepted, the logical inferences would seem to be correct. But inevitably there is doubt and confusion about the basic premise, and there are repeated efforts to reinterpret or misinterpret and to produce more satisfying results.

In the end, both views are rejected as perhaps one-sided and simplistic. The premises may be correct, and the logical reasoning impeccable, but the inferences may still be quite wrong. And that is where the additional speeches by Elihu and God come in.

In the three cycles of speeches by Job and his three friends, the positions do not change, and nothing much happens. In the speeches of Elihu (chapters 32–37) and Yahweh (chapters 38–41) however things do happen. In whatever way we explain the intrusive Elihu and his monologues, their present position in the text reflects an evaluation of what has Preceded: Elihu is highly critical of all the participants but especially of Job for his unacceptable assumptions and inferences about God’s relationship with humanity.

The final entry, however, is the voice from the whirlwind. Elihu directs most of his remarks to Job, although he does acknowledge the presence of the friends; so the voice from the whirlwind addresses Job directly and does not seem to acknowledge even the existence of Elihu.

The voice from the whirlwind is concerned about Job’s conclusions derived from the premise and the supporting data. It is not necessary for Job to condemn God in the process of exonerating himself. There is linkage, but Job hasn’t made the right correlations or deductions. He should go back to the drawing board.

At the end of God’s second speech, Job does repent—something that had been urged on him by his friends—but for entirely different reasons and in an entirely different connection. He does not budge on the question of his prior behavior: his oath of innocence stands firmly and forever. It is his faulty reasoning, his logical inferences that he is now willing to modify. The linkage between his suffering and divine malevolence is no longer so clear to him, nor presumably is the necessary contradiction between his righteousness and the loss of rewards. In the story everything will be resolved by the restoration of the status quo ante, and with compensation, but at the end of the Dialogue there is still some bewilderment. We might call that the beginning of a new wisdom on the part of everyone. All the humans have been wrong in greater or lesser measure. The ways of God remain mysterious, but it is possible to maintain faith and integrity in spite of inexplicable and often trying circumstances.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

A. First Cycle

1. Job: first speech, chapter 3

2. Eliphaz: first speech, chapters 4–5

3. Job’s reply chapters 6–7

4. Bildad: first speech, chapter 8

5. Job’s reply, chapters 6–7

6. Zophar: first speech, chapter 11

7. Job’s reply, chapters 12–14

B. Second Cycle

1. Eliphaz: second speech, chapter 15

2. Job’s reply, chapters 16–17

3. Bildad: second speech, chapter 18

4. Job’s reply, chapter 18

5. Zophar: second speech, chapter 20

6. Job’s reply, chapter 21

C. Third Cycle

1. Eliphaz: third speech, chapter 22

2. Job’s reply chapters 23–24

3. Bildad: third speech, chapter 25

4. Jobs reply, chapter 26

5. Job’s reply, chapter 27

The idea that Elihu speaks for Satan is affirmed in “The Testament of Job,” a pseudepigraphica work of the Roman period. Cf. J. H. Charlesworth The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, vol. I, pp. 829–868, especially pp. 860–863, where chapters. 41–43 are translated and discussed. Note especially Testament Job 41:5, “Then Elihu, inspired by Satan, spoke out against me …”; 43:5 “Elihu, the only evil one” and 43:17 “and the evil one Elihu.” I am grateful to my student John Kutsko for calling my attention to the references in the Testament of Job.