Is the Bible Right After All? BAR Interviews William Dever—Part Two

031

Continuing their wide-ranging conversation, excavator Bill Dever and Hershel Shanks turn to a crucial issue: How the Bible and archaeology can be used—and misused—to illuminate each other.

HS: What does it mean to be an Israelite in the 12th century B.C.E.? You call them proto-Israelites. What’s the difference between a proto-Israelite and an Israelite?

WGD: That’s a key question. I probably tend toward being a maximalist; others are minimalists. Tel Aviv archaeologist Israel Finkelstein says that we cannot use the word “Israelite” for this period; we cannot attach “Israelite” to the material cultural remains of the 12th and 11th centuries B.C.E. It is a legitimate question. By what warrant do we attach the label “Israel” to these 12th- to 11th-century B.C.E. settlements? For me, the Merneptah Stele is a very important datum. I take it seriously. I’ve used the term “proto-Israel” simply because the term “Israelite” in the Hebrew Bible probably doesn’t have much meaning that we can understand before the tenth century B.C.E., when the state emerges. By then, I think we know what it meant to be an Israelite. It was to be a citizen of this state. But in the 11th and 12th centuries B.C.E., when Israel was an amalgam, when it had not attained the degree of unity that comes with statehood, many Israelites would probably have been confused by the label. Maybe they didn’t call themselves Israelites. So I’ve adopted the term “proto-Israelite” because I would argue that these settlers are the predecessors of the fully developed Israelite settlers of the tenth century B.C.E. and later. I’m trying to be cautious, but I think before long we will simply be able to use the label “Israelite.” However, many dispute that. The whole question of ethnicity in the archaeological record is one of the hottest issues in archaeology today. And a great many people are very skeptical about any ethnic terms.

HS: How is an Israelite different from a Canaanite?

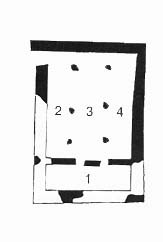

WGD: That’s precisely the question. Some would say we can’t know. As an archaeologist, I deal with material-culture remains. I am very cautious in trying to reconstruct ancient ideologies. I don’t know what these so-called proto-Israelites thought. I don’t think we do know until we have some texts from later periods. As an archaeologist, I can characterize the way they lived. I would try to talk about lifestyle. I would ask, in the 12th and 11th century B.C.E. hill country settlements, what is similar to the preceding Canaanite culture? And what is different? The pottery is similar. What is dissimilar is the house form, for instance. Here we see the so-called four-room house, or courtyard house, that I would understand as typical farmhouses. Therefore, I think we’re dealing with an agricultural people. Everything about these settlements indicates that the inhabitants are not urbanites. They are rural 032people. They are newcomers to the hill country, though not, I think, coming from outside Palestine. They have previously been farmers and stock breeders somewhere in Canaan. We have to look at their total lifestyle before we can even approach the problem of attaching an ethnic label.

HS: Doesn’t the Bible itself indicate that the tribes of Israel did not all come from outside?

WGD: Precisely.

HS: When the average person hears about the Israelites coming from Canaan, it’s presented as if that contradicts the Bible when in fact, if you look at the Bible and read it sensitively, you see precisely that.

WGD: Of course. I’ve always tried to stress that if we read the Bible with sophistication—not simplistically—we can often correlate the Biblical text with the archaeological remains—very often, I must say.

HS: The Bible tells us that the tribe of Dan was involved with the sea [“Why did Dan abide with the ships?” Judges 5:17].

WGD: And you have that marvelous passage in Ezekiel, it’s an ironic passage. The prophet has God saying, by way of criticism of the Israelites, “Your origin and your birth were in the land of the Canaanites” [Ezekiel 16:3]. Israelites knew their own origins. In time, they came to distinguish themselves as Israelites.

Ethnicity means a sense of peoplehood. Ethnicity is not simply a matter of differences in material culture. But you do have to try to get at ideology; otherwise, there is hardly any point in archaeology. It is difficult, but it is possible to read from pottery certain ideas. For instance, we always speculate about why a pot is made in this way, what it was used for.

In that sense, we are trying to get at a certain type of ideology, the idea lying behind the pot, the idea in the potter’s mind. But in the absence of texts, we can go only so far. For instance, if we did not have the Merneptah Stele, would I presume to call these 12th- to 11th-century B.C.E. people proto-Israelites? I doubt it. I would be very cautious about taking the Biblical name “Israel” from a later period in the monarchy and projecting it back this early. But where we do have the text, we should not deny its obvious implications.

HS: How does an ethnic group develop? To summarize what we’ve said, a group of people may well have come from Egypt, gone through Transjordan and settled in the hill country of Canaan. And there may have been 033some military actions, even some for which we have archaeological evidence. Some may have come without military action and settled peacefully. And still others, perhaps the majority, came from among the Canaanite population. How do these sources, these streams of people, come together and become something else that they weren’t before, a new ethnic group? How does that happen?

WGD: That’s precisely the question. I think we can describe how it happens, but I’m not sure we can say why. We can talk about cultural change over a period of a century B.C.E. or two. We can document that cultural change in pottery, in burial customs, in religious rites even. But when you ask the question “Why?” you are asking a philosophical question, and I don’t think the archaeologist can answer that.

HS: I’m not asking why, I’m asking how it happens and when they become a separate group. Let me draw an analogy. Take the problem of speciation in the history of evolution. How do you define a new species? It’s very simple. If you take some fish and you isolate them for enough generations, and then put them back with the old fish, they can’t get together with the old fish and produce new little fishes. They are a new species. It’s a very sharp line. What is the analogy to the reproductive process in the formation of a new ethnic group?

WGD: Evolution is much easier to describe and to specify in the biological sciences than in the study of cultural change. Whether early Israelites interbred with Canaanites I don’t know. I suspect they did. The development of a sense of ethnicity is always slow and gradual. There’s no single point at which you can say the Israelites now began calling themselves Israelites and no longer Canaanites. It happened over a period of at least two centuries. But at the end of that time, I think the Israelites did regard themselves as distinct from Canaanites and from the peoples of Transjordan.

By the way, we now understand that what was happening with early Israel in the 12th–11th century B.C.E. was not unique. What we’re dealing with is the process of forming several new nation-states and new peoples in the vacuum following the collapse of the Late Bronze Age world. It happened in Syria with the emergence of the Aramean states. It happened in Transjordan with the emergence of the Edomite and Moabite and Ammonite states. It happened with the emergence of Phoenicia along the Mediterranean coast. The Philistines, too, went through a long period of cultural assimilation and did not disappear at the end of the 11th century B.C.E. So Israel and Judah were part and parcel of a dozen or more peoples in this area of the world who were all in the process of defining themselves. We happen to know a lot more archaeologically about early Israel than we do about these other early 034nation-states. But sometimes that complicates the problem—we know so much and yet we don’t know quite enough to define the process in full. By the time we come to the tenth century B.C.E., we can distinguish Israelite sites from, let’s say, Philistine sites and Phoenician sites on the basis of material culture remains. What that means ideologically is much harder to specify. But for me it means this at least: These people knew themselves finally to be Israelites. They knew what that meant. It’s up to us to try to find out. I don’t despair. I don’t think we need to give up. If we cannot specify in some degree how ancient Israel was different, then we have failed in our task not only as archaeologists but as Biblical scholars.

HS: That we have failed up to now doesn’t mean we shouldn’t keep trying.

WGD: Precisely. I think we must keep trying.

HS: Did these other states or ethnic groups have a distinctive ideology?

WGD: We must presume that they did.

HS: Is that what distinguishes them? They are distinguished geographically.

WGD: Right. They are also distinguished in terms of pottery styles and other aspects of material culture. It’s true, of course, that all of these things overlap. The pottery of early Edom is not totally different from the pottery of early Israel. It is similar, but there are some distinctive elements. Those are the elements that the archaeologist tries to isolate.

HS: The most intriguing question for the layperson is the ideological one. What did the early Israelites believe and did most of them believe the same thing?

WGD: We don’t know what they believed, except where they expressed it in some sort of behavior that leaves a trace in the material remains. Secondly, as an operating principle, we ought to assume that they probably did not agree. The later writers of the Hebrew Bible did not agree either. Why should we expect that? Nevertheless, there must have been a kind of core of beliefs and customs that in time served to distinguish them. We 035know that it did do so, even if we don’t understand precisely how.

I have proposed that one way to work at this problem of ethnicity would be to pick three sites somewhere in Israel, one along the coast which we could presume to be Philistine, founded by the Philistines, and then take a site somewhere in the Jezreel Valley that almost certainly continues to be a Canaanite site in the 12th century B.C.E., and then take one of the hill country sites, presumably a proto-Israelite site, and excavate all these with an international team of scholars who have all agreed on methodology, on recording systems and the like, and do a dispassionate, objective analysis of the difference in material culture. I think it would be fascinating. It would be an experiment in trying to define ethnicity archaeologically. In time it will be done, I think.

HS: Even in the monarchical period [late 11th-early 6th centuries B.C.E.], we have evidence of disparate ideological and religious beliefs within Israel, don’t we?

WGD: Of course. This is reflected to some degree in the material remains. For instance, by the ninth and eighth centuries B.C.E. we can distinguish northern styles of pottery from southern styles of pottery. According to the Biblical tradition, the United Monarchy broke up on the death of Solomon. A northern kingdom [Israel] and a southern kingdom [Judah] were established. That’s reflected to some degree in the ceramic traditions. If you show me a water decanter of the eighth century B.C.E., I can tell you immediately whether it’s from Israel or Judah—based simply on the pottery, not on the Biblical tradition at all.

HS: We talked about the difficulty of determining ideology from material culture, but religious artifacts do reflect ideology, don’t they?

WGD: Without a doubt. But of course archaeologists will differ among themselves over what should be considered cultic. I may find an exotic vessel that I consider to be cultic and others will doubt it. Be that as it may, it is a fact that we have not discovered very much from these 12th–11th century B.C.E. settlements that could be considered cultic. Does that mean that the proto-Israelites had no religious beliefs? Of course not. It means that we cannot at the present stage of our research recognize those beliefs. [Hebrew University professor] Ami Mazar’s “bull site” is an Israelite cult site of that period.a For me, it’s interesting that the major find there is a bronze bull reminiscent of an old Canaanite god, El, whose principal title is bull. This suggests that what religious beliefs the earliest Israelites did have were largely Canaanite. I said that in a lecture when David Noel Freedman [editor of the Anchor Bible Dictionary and Anchor Bible Series] was present and he said, “Well, what’s the big news about the Canaanite origins of early Israel? For a century now, modern Semitic linguists have known that Hebrew is a Canaanite variant.”

Many things in early Israel come from a Canaanite background, according to the Bible itself. So we should not be surprised if religious customs do, too. Most of the agricultural festivals of early Israel go back almost certainly to the Canaanite cult. Why would the Hebrew prophets denounce the Canaanite cult so vehemently if it were not still present?

HS: Time and again, we seem to be coming back, Bill, to the idea that …

WGD: The Bible was right after all! [laughter]

HS: One of the glories of the Bible is that it does contain its own dissent.

WGD: Precisely—not only a glory, but it may be a unique aspect of the Hebrew Bible. I don’t know of any other literature from the ancient Near Eastern world that is so selective and yet so honest about what it includes. I give the latest editors of the Hebrew Bible a great deal of credit. I think they were good historians on occasion. I think they were far more sophisticated than we suppose, and I think they were puzzled by some of the same things that puzzle us. Therefore, they included in their account other versions. And they expected us to use our heads, to read the Bible critically, to engage in a dialogue with the text. There is more than one explanation of many things in the Bible, and we ought to take the alternate explanations seriously. I’ve often suggested that we archaeologists and historians must read between the lines, to look not only at what the Biblical writers say, but at what they allude to, what they avoid saying.

One of my colleagues in Biblical studies, [Rhodes College professor] Steve McKenzie, calls this “reading against the grain.” You have to see the Biblical writers’ intention, but then you have to speculate about what else they knew but did not choose to tell us, wringing more material out of the text than appears to be there at first glance. For me, the great excitement about archaeology is that it enables you to read the Bible from a new perspective. When I read a description about daily life in one of the Prophets, I am not thinking at that moment just about what the prophet is saying, I am thinking about what I know about the eighth century B.C.E., what it was actually like for the average Israelite. When I read the text, I read it with a sensitivity and an understanding that only a knowledge of archaeology can bring to the text. The text comes alive for me in a new way.

And I will say this, I do not see how many of the texts of the Hebrew Bible can have been invented in the Persian [sixth-fourth centuries B.C.E.] or the Hellenistic period [fourth-first centuries B.C.E.], because there are too many incidental details that ring absolutely true of earlier periods, based on what we know today. I want to write an article that I am going to entitle simply “Convergences,” and I’m going to list dozens of places where little snippets in the Hebrew Bible fit exactly with what we know of the monarchical period.

HS: Can you give me an example?

WGD: I can give you a hundred examples. The one that comes to my mind again 036and again is the reference in 1 Samuel 13:19–21 to the custom of the Israelites going down to the Sea Peoples in the coastal plain and having their tools and weapons repaired and sharpened because the Philistines had a monopoly on iron working. The text says the price for that service was one pym. That word occurs only there in the Hebrew Bible; it was never understood before this century when archaeologists discovered small, dome-shaped shekel weights inscribed in Hebrew, pym. We know exactly what the word pym means now. It’s a fraction shekel weight. We even know how many grams it weighed and we know a pym was a balance weight used to weigh out scraps of silver. Is it possible that a writer in the second century B.C.E. could have known of the existence of these pym weights, which occur only in the ninth to the seventh century B.C.E. and would have disappeared for five centuries before his time? It is not possible.

That’s only a small detail, you say. But the fact is there are hundreds of places in the Hebrew Bible where there are little descriptions like that of a past reality that could not have been invented later. So whatever you want to say about the editorial process, the final redactors [editors] of the Hebrew Bible are drawing on very old textual materials. At point after point after point, we can show that the context of these passages must originally have been early in the Iron Age [1200–1000 B.C.E.] or at least in the monarchical period. And again and again and again we can tie in events, in the Book of Kings, for example, to Egyptian, Assyrian and Babylonian records.

So I think there is a historical framework here. There is a great deal of historical detail in the Deuteronomistic History as we have it in Joshua through the Book of Kings. That doesn’t mean every bit of it is true. And certainly the writers recast the whole story to suit the theological needs of the Exile and the post-Exilic period. But the writers of the Bible were good historians when they meant to be. Often they were not interested in writing history, but they certainly could. I think Baruch Halpernb was right. The Deuteronomist was the world’s first historian, earlier than the Greek historians.

But of course the Bible is not, in the final analysis, about history at all. It’s about His Story. But there is history there as well.

HS: You say that as an archaeologist you are able to read the Bible more sensitively and in a different way. Tell me how you react when you pick up some eighth-century B.C.E. pillar figurines of women with large exposed breasts and flaring skirts, apparently fertility figurines. How do you bring that to the Biblical text?

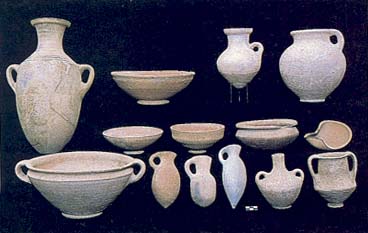

WGD: This is a good example to illustrate my basic methodology. You do not start with the Biblical text. The Bible has at least a half dozen Hebrew terms for figurines or images or idols of some sort. You don’t start with an exegesis of those texts and then go to a site looking for something like that. I start, as an archaeologist, with a discovery of these figurines, of which we now have more than 3,000. My task is to understand them in the context of their time. I don’t think they’re dolls or toys. I think they are female fertility figurines, and I think they can be identified specifically with the goddess Asherah, about whom we know a great deal, not only from the Biblical text but from archaeological discoveries. So I call them Asherah figurines. In comparison to the Canaanite figurines of an earlier period, they are rather more modest. They emphasize the breasts only, not the lower body. They are more chaste. I think therefore they reflect the Israelite conception of the mother figure not so much as the consort of the chief male deity but rather as the patron of mothers who wish to conceive and nurse children and raise them through infancy.

It’s clear these things were used by the majority of Israelite women. Exactly what they thought when they used them, I don’t think we know. After I have tried to interpret them from an archaeological or historical point of view, then I go to the Biblical text. I see if I can make a connection. I think that’s legitimate to do in a second stage of our research because if we have texts that talk about images of some sort in the Iron Age, it is irresistible to ask whether or not these are not illustrations of the text.

The odd thing is, we cannot connect any of the Biblical terms precisely with these figurines. What does that mean for historiography? Did the Biblical writers not know about these things? They must have known about them. Then why don’t they mention them in a way that we can figure out? Are they embarrassed by them or are they trying to suppress them? I don’t know. But it is a fact that we cannot make a direct connection between these thousands of female figurines and the language in the Bible. Why not? I would not say it’s because 037the text was written later when these things had gone out of use. I think the writers of the Hebrew Bible did not tell us very much about popular religion because they didn’t approve of it. They did tell us something about it. They condemned images. Why condemn them if they didn’t exist? They condemn the cult of Asherah. Why condemn it if it wasn’t extremely influential? So once again, if we read between the lines in the text, we can discover more than perhaps the writers wanted us to know.

HS: Do you think that it was part of popular Israelite religion that Yahweh, the Israelite God, had a female consort?

WGD: We know that in the neighboring cultures, deities were usually paired, a male and a female. Why should Israel be any different? What the average Israelite believed about Yahweh, we really don’t know. We know that according to the official version given to us in the Hebrew Bible, most Israelites were monotheists. We also know that that is not likely to have been true. The only way that we can reconstruct popular religion is really through the negative approach to the Bible. In the condemnations, we can read something. And then we can do it through archaeological remains. In the last 10 or 15 years, we’ve discovered a great deal about the ancient Israelite cult. It now appears that we have to take the cult of Asherah, the mother goddess, much more seriously.

HS: Some of our readers object to the use of the word cult because it raises images of cults today and mindbending and exotic religions. Why do you use the word cult, why not religion?

WGD: I use the word cult in its proper meaning, to specify religious practice, because that’s what the archaeologist can deal with better. The term religion is too broad. Religion includes belief; most archaeologists are not able to specify belief. I’m not using cult in any negative sense at all. I use it in an etymological sense to refer to religious practice.

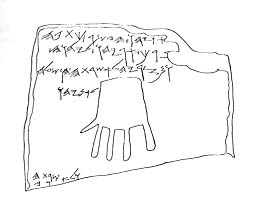

We ought to expand on the idea of Asherah as a consort. No one 20 years ago would have suggested that Yahweh had a consort. It is the result of archaeological discovery that we had to confront Asherah. She is almost forgotten in the pages of the Hebrew Bible, although, as you know, there are almost 40 references to an Asherah or the Asherah, which may be either a symbol of the goddess or in some cases the goddess herself. But those references are rather difficult to understand. With the discovery of the Khirbet el-Kom inscriptions in the late 1960s and the Kuntillet Ajrud materialc in the 1970s, we now have two Hebrew texts that refer to Asherah and couple her, or “it” if you think the Asherah reference is only a tree-like symbol, with Yahweh. We now know that the cult of Asherah in ancient Israel was widespread. That’s why it’s condemned by the writers of the Hebrew Bible.

HS: So again, if you read the Biblical text sensitively, you suddenly find confirmation.

WGD: Yes, precisely. When people seem shocked at this new interpretation of Israelite religion, I point out to them that we might have known this already from the Biblical text alone. But here again, archaeology has helped us to understand those texts in a new light.

Inevitably our own cultural background influences our interpretations in archaeology. There is no such thing as an entirely objective look at the past. We like a certain kind of history because it is our history.

HS: It’s also true, is it not, that some researchers are more biased than others, and it’s also true that we have an obligation to examine our biases and to suppress them. And some of us are better at suppressing them than others.

WGD: Right. Couldn’t be better put. One of the advantages of the more self-conscious way we approach archaeology today is that we may be more aware of some of our biases than the previous generation was. I try to be aware of mine. The goal of course is to separate description from interpretation, so that if we are wrong in our interpretation, a later generation is able to correct it.

HS: What do you think the future of Biblical archaeology is?

WGD: Defined as a dialogue, as I want to 074define it, I’m not sure what its future is. I would like to say that I see much more dialogue between archaeologists and Biblical scholars than 20 years ago, but I’m not sure that’s the case. Archaeologists are becoming highly specialized. Many of them are no longer interested in the dialogue with Biblical studies. Many of my own students are not interested. Many of the Israelis are not interested. And those few who are interested are increasingly wary of providing any sort of synthesis because it seems obsolete almost as soon as it’s published. All the old syntheses are falling apart. Ours will too.

HS: Does that mean we shouldn’t keep trying?

WGD: No, of course not. I keep trying. But it means that you have to be very bold to venture into print now. And you are certain to be attacked from all corners. I’m attacked today because I stand somewhere in the middle on these issues. I get it from all sides. There is a great reluctance today to do any sort of synthetic work. Biblical scholars, like archaeologists, are becoming highly specialized. Many of them are theologians and are not interested in other approaches to the Biblical text.

If you read the current literature, there is really very little exchange of ideas between Biblical scholars and archaeologists. I regret that. I’ve spent my life trying to create such a dialogue, but honestly I don’t see it happening. I don’t see it happening in Europe because the Europeans are not doing much archaeology, at least not in Israel. It’s not happening in Great Britain. The British were never much interested in Biblical archaeology. It’s not even happening in Israel. And very few of us in this country are writing on the kinds of issues we’ve talked about today. I think it’s a great tragedy because Biblical scholarship has finally matured, and so has archaeology. That’s what I had hoped would happen: two mature disciplines in dialogue with each other, each approaching the study of the past with its own distinctive data and objectives. If there is to be no dialogue, then I think it is a great loss for both disciplines. I think Biblical studies will suffer and archaeology will suffer.

HS: How can this be corrected? How can we create this fruitful dialogue that you are talking about?

WGD: I think one way would be to teach more archaeology in seminaries, where the next generation of Biblical scholarship is being trained. Archaeology is scarcely taught anymore in American seminaries. And some of those who are teaching there 075will find that when they retire they are not replaced. Archaeology is perceived by most seminaries as a very exotic, very expensive enterprise, best left to the specialists. I would hope that we could create some positions for archaeological specialists, just as we have for textual specialists. Most Biblical scholars ought to have some field experience [in archaeology]. A summer or two on an excavation would make them more critical in reading archaeological reports. On the other side, I still believe that all archaeologists working in Israel must have sound training in Biblical studies. I insist that my students have it. Even if they are working in Jordan, they must know the Hebrew Bible.

HS: Archaeology is so fascinating to the general public. Obviously my first evidence of this is the popularity of BAR. Yet you tell me that archaeology isn’t being taught in the seminaries. How do you account for that discrepancy?

WGD: You are quite right. There is an enormous groundswell of popular interest in archaeology, but it does not translate into new positions in seminaries or universities.

HS: Why not?

WGD: I don’t know. I think it may be partly our fault. We have not succeeded in mainstreaming Palestinian or Jewish archaeology, despite our efforts—despite your efforts. Not until the American public demands that institutions teach this subject will it be taught. It needs to be taught, not only in seminaries where it used to be taught, but in universities. I have always argued that we need to be communicating the results of Palestinian or Biblical archaeology in every way we can. We need to be training people in a variety of ways, placing them in a variety of institutions. But the fact is that we have not been successful in that.

HS: Sometimes you are blamed for part of this because you are perceived as being against Biblical archaeology. Would you object to a course in a university called Biblical archaeology?

WGD: Most universities would object. You can say it a different way. You can say “Archaeology and the Old Testament” or “Archaeology and the New Testament.” Such a course would be legitimate.

HS: But how about a course in Biblical archaeology?

WGD: It would attract mostly students who are majoring in religion. You want to attract them, but you also want to attract students who are, let’s say, anthropology majors or Near Eastern studies majors. The label “Biblical archaeology” is unfortunate.

HS: Certainly BAR attracts all sorts of people who have an interest in the Bible and want to learn about the illumination archaeology can provide.

WGD: That’s fine. That’s an important audience, but you know as well as I that it’s not the only important audience. That’s one of the problems. We have interpreted the archaeology of Israel and Jordan too narrowly, as though it were of interest only to those who start from the point of view of Biblical concerns. There is a much broader interest.

HS: But don’t you have to recognize the fact that the primary interest of people in archaeology of this area is because of their interest in the Bible, which is their roots, their history, their background? That’s why they are more interested in that than, say, the archaeology of Afghanistan.

WGD: There’s no doubt that the primary interest in the so-called lands of the Bible has been the Bible. But unless we can 076broaden the support for archaeology of the Bible lands, it will collapse.

HS: You have talked about the importance, to use your own words, of “marketing” our subject. I don’t understand why you wouldn’t teach a course that would be very attractive to many students of all stripes if you called it a course in Biblical archaeology.

WGD: No, labels are significant. I have taught a course regularly every other year, “Archaeology and Biblical Studies.” Many of us teach such courses. I doubt you find those courses labeled “Biblical Archaeology,” even in seminaries.

HS: Are they popular courses?

WGD: Frankly, they are not as popular as I think they ought to be. Several times I have had trouble drawing 15 to 20 students for a course in “Archaeology and Biblical Studies.”

HS: That’s surprising, isn’t it?

WGD: It surprises and disappoints me. I think we’re seeing a generation of American students who were not raised on the Bible. One of my notions in the beginning was that the archaeology of Palestine, or Israel and Jordan, ought to outgrow its rather narrow Biblical base of support. But it has not done so; I will admit that. When I think about the future of the discipline, the question is really just the question you implied, “Can America sustain an interest in the archaeology of Israel without the Biblical motivation that inspired the founders?” I am not sure that it can.

I think the desire to understand the past is fundamental. I think it helps us to shape our notion of who we are. I think it helps to guide us into the future. I take it very seriously. It’s not just a game for me. It’s a vocation.

HS: We’re all getting older; your generation is now the senior generation. Do you see a failure by these senior scholars to attempt syntheses, to attempt magnum opera?

WGD: It is a failure. We simply have to face it. Of course, the previous generation did not produce their grand syntheses either. Albright’s great lifetime work was to be a history of Israelite religion, which he never wrote. [Retired Harvard University professor] Frank Moore Cross’s great work was to be the same, but he never wrote that, either. Ernest Wright [Dever’s teacher at Harvard] told me in the last three weeks of his life he had hoped to write an Old Testament theology. He never lived to do that. Part of it is just that we are mortal. We have good intentions, but we don’t live long enough.

There’s another kind of failure that troubles me more. And that is the failure to bring it together in a way that will last beyond our lifetime. Perhaps that’s inevitable. I’ve been extremely critical of Albright. My students are already now beginning to be extremely critical of me. That didn’t happen to Albright until his death. That’s happening to me in my lifetime. That makes one wonder if anything does last. That’s one of the difficult things about growing older in a field in which you’ve been extremely active. You live long enough to see much of your own work rejected. However, since the rejection is coming in large part from my own students, I take some comfort that I trained them to be critical after all.

Ernest Wright, again in the last weeks of his life, reflected on how far his students had departed from his own views, myself chief among them. On the one hand, he was hurt by this, there’s no question about it. On the other hand, he took a certain pride in the fact that his students would go beyond his work. I think that’s why it’s hard to be a teacher if you take it seriously. What you teach your students they will, in the end, use to reject your own views.

HS: What should be the agenda for senior scholars in archaeology and the Bible today?

WGD: I think it’s right to pose the question that way because the agenda is different for my generation than it is for the upcoming generation. For the upcoming generation, I think the agenda will be to survive professionally, to be able to go on doing good fieldwork among rising costs and political tensions in the Middle East. Survival is the name of the game for them.

I’m now beginning to reflect on a lifetime’s work, and the first priority for me is to publish the last two volumes of field reports that I owe—one more volume on Gezer and then one more volume of my Early Bronze IV excavations. Beyond that, I would like to co-author a social history of ancient Israel and Iron Age Palestine, and I am working on it. I had hoped also to live long enough to write a critical history of Palestinian and Biblical archaeology. I doubt that I’ll ever do that. But I cannot go on excavating. One of the problems is that people of my generation, Americans and Israelis, thought that they could go on doing fieldwork forever, and they simply didn’t live long enough to publish.

When you are young, you should be doing fieldwork. When you are in your middle years, you should be training graduate students. When you are in your later years, you should probably be doing synthetic work. I’m trying to move to that phase. It’s not easy, but it must be done.

HS: Why is it so difficult to write a synthetic work?

077

WGD: Well, the temptation of going back into the field is always there, partly because fieldwork is enjoyable, it’s challenging, the human relations are exciting—and the thrill of discovery. Part of it is because you think you’ll solve some of the problems by generating new data. But of course what happens is you raise new questions. So at a certain time you have to discipline yourself. You just have to stop. It’s not that you’re too old to do fieldwork, it’s that it’s time to do something else. I had hoped to be out of the field by my middle 50s. I was, as a practical matter. Many people keep on excavating far too long. They simply won’t live long enough to publish. It takes 20 years on the average after you stop fieldwork to complete the publication. That indicates that you ought to stop somewhere in your middle 50s or at 60 at the latest.

HS: Why do you suppose you’ve been so controversial?

WGD: Archaeology is a controversial discipline. I have chosen some battles and entered them deliberately because I felt they were important. I always had a certain confidence, a brashness, you might say. That’s probably more a matter of temperament than anything else.

Most of the areas I’ve written in have been controversial, but in some cases it was not I who created the controversy. I find controversy personally painful at times. I don’t think I’m necessarily a combative person. I do find myself involved in controversies. And when I am, I am bound to defend my position. Among my many virtues, modesty is not the most outstanding. I have strong ideas, and I hold them strongly. I regret that that doesn’t result in greater consensus, because I think the point of controversy is to move finally towards some sort of convergence. Often, we don’t.

HS: Don’t you think that the development of a rather thick skin is a prerequisite for a scholar in this field?

WGD: Yes. I didn’t know that when I was young. When I began my career, I was quite innocent. When I first began to criticize Biblical archaeology, I had no idea of the furor it would cause. I read my first article to my wife, and she said, “You better not publish this.” And I said, “No one will notice. And who will care anyway?” So part of it, I got into innocently. Other controversies I entered deliberately. And sometimes I get involved in a controversy because it seems to me someone must.

HS: But no controversy that you have been involved in has had the public interest that the “Biblical archaeology” controversy has.

WGD: For obvious reasons. How many people in the general public are interested in the fine points of Middle Bronze chronology? Nobody reads those things that I write. One of the ironies of my career is that I may be remembered for a number of minor things that I did. Much of the major research that I’ve done is mainstream archaeological research; it is not going to appeal to the public. It is not controversial. If you look at the whole body of my publications, my concern with Biblical questions has been a very small part of my work.

HS: And you think you may be remembered for the controversy over “Biblical archaeology”?

WGD: Yes. That would be unfortunate. I think my long-term contributions will lie in other areas. I hope so.

HS: I think you’re right.

WGD: What I hope to leave behind besides some headlines and a few books on the shelf will be a generation of well-trained students who will carry on the kinds of research concerns I’ve had. That’s the ultimate compliment to any teacher. I care more about my students and what they think than what anybody else thinks.

HS: Thank you very much, Bill.

Continuing their wide-ranging conversation, excavator Bill Dever and Hershel Shanks turn to a crucial issue: How the Bible and archaeology can be used—and misused—to illuminate each other. HS: What does it mean to be an Israelite in the 12th century B.C.E.? You call them proto-Israelites. What’s the difference between a proto-Israelite and an Israelite? WGD: That’s a key question. I probably tend toward being a maximalist; others are minimalists. Tel Aviv archaeologist Israel Finkelstein says that we cannot use the word “Israelite” for this period; we cannot attach “Israelite” to the material cultural remains of the 12th and 11th […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username