Try to imagine flying to a non-existent island on an airplane that has not yet been invented. Even if this impossible trip were to take place during the thirteenth month of the year, it would not be as fantastic as the tale, recently christened as scientific certainty by some New Testament scholars, concerning the “Lost Gospel” of Q.

The story of Q (short for the German Quelle, meaning “source”) is not exactly hot off the press. It began over a century and a half ago. At that time it was part of the two-source theory of gospel origins. In the wake of Enlightenment allegations that the Gospels were historically unreliable, some suggested that their origins were primarily literary. Matthew and Luke, the theory went, composed their Gospels not based on historical recollection but by using Mark and a hypothetical document called Q as dual sources.

The theory was not without its difficulties, and it is no wonder that many Anglo-Saxon scholars—B.F. Westcott (1825–1901) would be a good example1—as well as formidable German-speaking authorities like Theodor Zahn (1838–1933) and Adolf Schlatter (1852–1938) declined to embrace it. But it gained ascendancy in Germany, and to this day enjoys a virtual monopoly there and widespread support in many other countries.

The much-publicized Jesus Seminar has pushed Q into popular headlines of late.a But behind the Jesus Seminar’s exalted claims for Q lies an interesting history. Key players in the Q revival include Siegfried Schulz, with his 1972 study, The Sayings Source of the Evangelists.2 Schulz speaks of a Q-church in Syria that hammered out Q’s final form in the A.D. 30–65 era.3 The “gospel” they produced, later absorbed into the canonical Matthew and Luke, lacked Christ’s passion, atoning death and resurrection. Q, it was alleged, contained only a series of sayings. The upshot of Schulz’s work: A primitive “Christian” community produced a “gospel” lacking the central foci of the four canonical versions, Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. Q was suddenly no longer an amorphous source, but a discrete witness vying for recognition with its canonical counterparts.

In some ways Schulz had been scooped by the slightly earlier study of James M. Robinson and Helmut Koester.4 But it is only recently that a phalanx of studies by Robinson, Koester, John Kloppenborg, Arland Jacobsen and Burton Mack have in effect expanded on Schulz’s work.5 Mack breaks Q down into four stages: proto-Q1, Q1, proto-Q2 and Q2—asserted in detail without the slightest attempt to furnish proof. To save this house of cards from collapse, the so-called Gospel of Thomas is being pressed into service today to give Q ostensible support.

The cumulative weight of these studies is captured in Stephen J. Patterson’s statement in BR that “the importance of Q for understanding Christian beginnings should not be underestimated. Mack is surely right in asserting that a better understanding of Q will require a major rethinking of how Christianity came to be. Together with the Gospel of Thomas, Q tells us that not all Christians chose Jesus’ death and resurrection as the focal point of their theological reflection. They also show that not all early Christians thought apocalyptically.”6

Patterson is enamored enough of Mack to quote him favorably on a further point that Patterson (wrongly7) claims most New Testament scholars share: “‘Q demonstrates that factors other than the belief that Jesus was divine played a role in the generation of early Jesus and Christ movements…[As a result] the narrative canonical gospels can no longer be viewed as the trustworthy accounts of unique and stupendous historical events at the foundation of the Christian faith. The gospels must now be seen as the result of early Christian mythmaking. Q forces the issue, for it documents an earlier history that does not agree with the narrative gospel accounts.’”8

Now we discover the truth: Q, the hypothetical sayings gospel, is the lever needed to pry the Christian faith out of its biblical moorings. Not the Gospels but Q must be faith’s new anchor, inasmuch as Q is earlier than the Gospels and does not agree with them. Q settles the matter.

Poor Christianity. Are sackcloth and ashes in order because we have followed the wrong gospels, overlooking the real sole authority—Q? Or is it rather time to bar the enthronement of a false gospel, following Paul’s counsel and God’s Word: “If anyone is preaching to you a gospel contrary to that which you received, let him be accursed” (Galatians 1:9)?

Just what is Q, anyway?

The rhetoric used by Patterson and Mack is telling: “Q originally played a critical role”; “Q demonstrates”; “Q forces the issue”; “Q calls into question”; “Q tells us.”9 Assuming Q ever existed in the first place, isn’t it just a hypothetical source, a lost piece of papyrus, an inanimate object? But Patterson and Mack’s language make a dead thing into a commanding personal authority. This is the stuff of fairy tales.

The practitioners of this New Testament “science”—despising God’s Word in the Gospels as “the result of early Christian mythmaking”—have created a new myth, not only the enchanted figure of Q but also Q’s storied people: “‘The remarkable thing about the people of Q is that they were not Christians. They did not think of Jesus as a messiah or the Christ. They did not take his teachings as an indictment of Judaism. They did not regard his death as a divine, tragic or saving event. And they did not imagine that he had been raised from the dead to rule over a transformed world. Instead, they thought of him as a teacher whose teaching made it possible to live with verve in troubled times. Thus they did not gather to worship in his name, honor him as a god, or cultivate his memory through hymns, prayers and rituals. They did not form a cult of the Christ such as the one that emerged among the Christian communities familiar to readers of the letters of Paul. The people of Q were Jesus people, not Christians.’”10

Really?

What can we know for sure about Q?

Ancient sources give no hint that such a source ever existed. Among the early Church fathers, there is not even a rumor of some lost gospel. Far less is there a hint that any of the gospels were produced by the use of written sources. And there is not the slightest textual evidence that some lost sayings gospel Q ever existed, although it is claimed today that Q was so widespread that Matthew and Luke (and maybe even Mark) each had copies of it independently.

Paul never mentions Q. Yet, if it existed, he could hardly have been ignorant of such a virulent influence, so contrary to the faith he championed. Paul would not have known the four Gospels (they had not yet appeared), but there is no reason why he should not have known Q if it really existed in the decades before the appearance of the Gospels.

Q allegedly developed between the years 30 and 65 and still existed when Matthew and Luke wrote, commonly regarded as the last quarter of the first century, else it could not be copied by them. Three decades would have given Paul ample time to encounter Q. If the Q-people were the earliest “Jesus movement,” they must have founded a church in Jerusalem. Peter and Barnabas, coming from there, would have known Q and would have introduced Paul to it in Antioch in the early 40s. Paul would have encountered it and the “Jesus people” of Q at the latest around A.D. 49 at the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15). Are we to believe that this Council was content to quibble over the interpretation of Jewish law, as Luke reports, when Paul was “mythologizing” the gospel, claiming Jesus to be God’s son, while the Q people held him to be no more than a sage?

If “the people of Q were Jesus people, not Christians,” conflicts would have been inevitable. How could these conflicts have left no trace in Acts or in any of Paul’s letters? How could Paul have written to the Corinthians that he delivered to them what he had received—that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures (1 Corinthians 15:3)—if the atonement at the cross was only a brand-new, mythological idea, not accepted by the earlier followers of Jesus, who “did not regard his death as a divine, tragic or saving event”?11

Either Paul, “called as an apostle by Jesus Christ by the will of God” (1 Corinthians 1:1), is a liar or the current crop of Q theorists is spinning yarns. We have to choose.

In fact, Q’s existence cannot be corroborated from manuscript evidence, Paul’s letters or the known history of the early church. Q and the Q people are a historical fiction, no more real than the man in the moon. It would be intellectually irresponsible to rethink Christian faith based on such a tale.

Q was unheard of until the 19th century. It has never been anything but a hypothesis, a supposition that Matthew and Luke might have taken their common material from a single written source.

Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834) got the modern ball rolling by twisting a statement of Papias (c. A.D. 110), in which the church father says that Matthew compiled

Schleiermacher proposed that Matthew wrote only the sayings, not the gospel itself, a view lacking support in both ancient church tradition and in Matthew’s Gospel. If one were to sort out all “sayings” from Matthew, the result does not resemble what is called Q today. Q, as proposed by the Q-theorists, does not contain all the “sayings” found in Matthew’s Gospel, nor does the Gospel consist merely of “sayings.”

Christian Hermann Weisse (1801–1866), wanting to account for the sayings in Luke, built on Schleiermacher’s error.14 Weisse claimed that this sayings-source was used as a source by Luke too. This misused Schleiermacher’s theory for Weisse’s own purposes.15 And so the infamous Q made its debut in the theological world.

We likewise have Weisse to thank for the invention of the Lachmann fallacy,16 which wrongly asserts that Karl Lachmann proved that Mark was also used as a source by Matthew and Luke; in fact Lachmann argued just the opposite—that Mark was not the source for Matthew and Luke.

The world-renowned two-source theory—the notion that Matthew and Luke were based on Mark and Q, the basis for perhaps 40% of so-called New Testament science today—was therefore founded on both (Schleiermacher’s) error and (Weisse’s) lie.

Let us look closely at the alleged Q to see if we can find its presence in Matthew and Luke.17

We concede the obvious at the outset that, besides the pericopes that Matthew and Luke have in common with Mark, there is a good deal of material that Matthew and Luke share. Siegfried Schulz lists 65 pairs of passages that are parallel in Matthew and Luke. But similarity in content is in itself no proof of literary dependence. It could also be caused by the same event: a saying of Jesus, for instance, reported independently by several different persons who heard it. In other words, similarities might have been historically, and not exclusively literarily, transmitted.

Nor can the existence of Q be inferred from literary sequence. The differences in the order of the alleged Q-material in Matthew and Luke are enormous. Only 24 of Schulz’s 65 pairs of parallels, or 36.9%, occur within a distance of no more than one chapter of each other. Only five of them (7.69%) occur in the same point of the narrative flow in Matthew as in Luke (or vice versa). It takes a robust imagination to suppose that, despite such differences, the pericopes claimed for Q based on similarities in literary sequence owe their origin to a common source. But imagination is no substitute for evidence, and guesses as to whether Matthew here or Luke there diverged from Q’s sequence do not prove that Q existed.

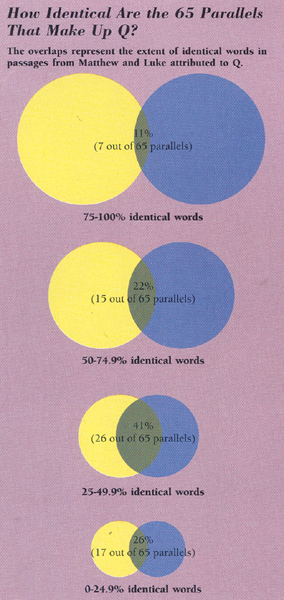

The main test for the existence of Q, and “the only safe test for literary dependence,”18 is identity in actual wording. In Q’s 65 pairs of parallels between Matthew and Luke, the number of words in Q’s Matthean form amount to 4319, in Luke’s 4253. The number of identical words in these parallel verses is 1792, or 41% of Matthew’s Q portion and 42% of Luke’s. This parallel material consists mainly of sayings of Jesus, which in the Synoptic Gospels do not vary much. For example, sayings of Jesus found in two of the three Synoptic Gospels have about 80% identical words. Based on my earlier research, this led me to expect that the percentage of identical words in the alleged Q material in Matthew and Luke might be 80% as well. But (as shown in the chart) the percentage of identical words turns out to be only about 42%.

In 17 of the 65 parallel pairs alleged to have come from Q—fully one quarter of Q—the number of identical words in parallel passages is less than 25%.19

In 26b of the 65 parallel passages—41% of Q—the number of identical words in parallel passages is between 25% and 49.9%.

In 15 passages of the 65—or 22% of Q—the number of identical words in parallel passages is between 50% and 74.9%. In 7 passages of the 65—or 11% of Q—the number of identical words in parallel verses is between 75% and 100%.

Of the 65 parallel passages in Matthew and Luke, one half (53%) contain fewer than 50 words. For comparison, the easily memorized Psalm 143 has 43 words.19 About 30% of Q’s passages contain 50–99 words; Psalm 23, also easily memorized, has 115 words. That is to say, 82% of Q consists of blocks of fewer than 100 words in length.

Is it preposterous to suggest that Jesus’ disciples, who sat at his feet and were sent out in his name for three years’ time, could have preserved such reminiscences, which assumed varied shapes in the telling, by memory? Is a hypothetical written document needed, or even reasonable, to account for the overlap in Matthew and Luke in these sayings passages?

I have counted all the rest of the Q passages, too. Five contain 100–149 words, and six contain 150–199 words. Just one contains 250–300 words.

If Q were a written source relied on by Matthew and Luke, then we would expect little variation between pairs of long sayings and pairs of short sayings. But if the saying was passed along orally, based on memory, we would expect that the longer passages would differ more than the shorter passages. What does the evidence show?

In the longest alleged Q passage, the Parable of the Talents (Matthew 25:14–30), only 20% of its words (60 out of 291) are identical with the Lucan parallel (Luke 19:11–27). Out of these 60 identical words, nine are the word “and,” seven are articles and six are pronouns scattered throughout the pericope. This leaves only 38 words out of 291 that Q-theorists must rely on to establish literary dependence. Most of the identical words (47 of 60, or 78%) occur in direct speech.

The differences between Matthew and Luke in this passage far outnumber the 60 identical words. In fact these differences total 310, which is 107% of Matthew’s 291 words!

The one passage in which all of Matthew’s words are also in Luke (Matthew 6:24 and Luke 16:13), consists of only 27 words. This is the same as the tiny Psalm 117 and not even half as much as the Great Commission, Matthew 28:18b–20, which many know by heart. Thus the similarity is easily accounted for by a historically reliable memory that reached both Matthew and Luke.

The longest passage in the 75%–100% agreement category contains just 78% identical words. The whole passage is about the length of Psalm 1, again a text that many know by heart. It is not difficult to imagine accounts of this length being committed to memory in the oral culture of Jesus’ day.20

What can we conclude from these statistics? Simply that there is no convincing evidence for the alleged Q in Matthew and Luke. There is not even any persuasive evidence in favor of such a hypothesis. Rather, the difficulties of the hypothesis are legion. The differences in order, and the percentages of identical wording, argue against literary dependence, since the differences are much higher than the similarities. The Q-hypothesis does not solve a problem but rather creates problems—which then require additional hypotheses to remedy.

The Gospels do not entail a problem if we are willing to abide by what the texts themselves and the documents of the early church tell us: The Gospels report the words and deeds of Jesus. They do this partly through direct eyewitnesses (Matthew and John) and partly through those who were informed by eyewitnesses (Mark and Luke).21 The similarities as well as the differences in the Gospel accounts are just what one expects from eyewitness reminiscence.

But what about Thomas?

The Gospel of Thomas plays a large role in the new debate about Q. Patterson writes: “Scholars took a long time deciding just what Q was. The sheer fact of its nonexistence was no small problem—and an obvious opening for Q skeptics. In recent years, however, resistance to the idea of Q has largely disappeared as the result of another amazing discovery: a nearly complete copy of the noncanonical Gospel of Thomas.”22 “The gospel of Thomas is a recollection of sayings of Jesus. The Gospel of Thomas shows that a gospel without a passion narrative is quite possible. A theology grounded on Jesus’ words, without any particular interest in his death, is no longer unthinkable. The Gospel of Thomas, which also has little interest in Jesus’ death and resurrection, in effect forced this reevaluation.”23 “Together with the Gospel of Thomas, Q tells that not all Christians chose Jesus’ death and resurrection as the focal point of their theological reflection.”24

Does the Gospel of Thomas indeed prove how the oldest gospel, the alleged Q, was shaped—consisting mainly of sayings, with no passion or Easter reports? That would be like saying that a young man who leads a rock-and-roll band must have had someone in his grandfather’s generation who played rock music as well.

The Gospel of Thomas is mentioned or quoted by some Church fathers in the first decades of the third century. Recent scholarship dates its earliest possible composition to about A.D. 140 (though the only complete manuscript is a Coptic translation dating to around A.D. 400). Even if this hypothetical dating is correct, that is more than 70 years after our canonical Gospels. By that time the true Gospels and the very expression evangelion (gospel) were well established; understandably a new creation like Thomas would try to traffic in this good name by claiming the Gospel title. But nothing here supports the theory that Thomas was a model for Q in the A.D. 35–65 time span. The Gospel of Thomas is not just “noncanonical.” Every Church father who ever mentioned it called it heretical or gnostic. From a gnostic document we cannot expect interest in Jesus’ death and resurrection, since gnosticism repudiates both as the early church understood them. So how can a heretical writing rightly be taken as the prototype for constructing canonical ones?

It is important to recall here that an actual “Q gospel” sans passion and Easter narratives does not exist. It is rather extracted from Matthew and Luke—which in every form known to us do contain the passion and Easter material.

William R. Farmer has recently suggested why the heretical Gospel of Thomas is being pushed to play so large a role in reconstructing early Christianity: “Because Thomas is a late-second to fourth-century document, by itself it could never be successfully used to lever the significance of Jesus off its New Testament foundation. Similarly, the sayings source Q, allegedly used by Matthew and Luke, by itself could never be successfully used to achieve this result. But used together, as they are by a significant number of scholars, Thomas and Q appear to reinforce one another.”25

You cannot erect a house of cards with a single card. You might lean two cards together as long as no wind blows. But can you live in such a house of cards?

Let us return to our original question: Is the Lost Gospel of Q fact or fantasy? The answer is now clear.

As a modest hypothesis undergirding the two-source theory, Q turns out to be based on an error. It has been promoted without thorough examination. Put to the test, it proves untenable.

As co-conspirator with the Gospel of Thomas to undermine the whole of Christian faith, Q is nothing but fantasy. The same goes for the literary shuffling used to discern various layers in it. So why are earnest scholars willing to indulge in such fantasies?

“At issue today is whether the death of Jesus should be regarded as an unnecessary or an essential part of the Christian message. The trend among New Testament scholars who follow the Thomas-Q line is to represent Jesus as one whose disciples had no interest in any redemptive consequence of his death and no interest in his resurrection.”26

This critical assessment is borne out in Stephen J. Patterson’s essay in BR, particularly in its closing sentences: “Together with the Gospel of Thomas, Q tells us that not all Christians chose Jesus’ death and resurrection as a focal point of their theological reflection…The followers of Jesus were very diverse and drew on a plethora of traditions to interpret and explain what they were doing. With the discovery of the Lost Gospel, perhaps some of the diversity will again thrive, as we rediscover that theological diversity is not a weakness, but a strength.”27

The motive is clear. Q (with Thomas’ aid) gives a biblical basis for those who do not accept Jesus as the Son of God, reject his atoning death on the cross and deny his resurrection. Then, these same scholars combine their newly minted biblical basis with early Church diversity to justify calling themselves “Christians” despite their aberrant convictions.

By trumpeting the claim that today’s new Q-Christians are in sync with earliest historical origins while traditional Bible believers hallow “the result of early Christian mythmaking,” they lay down an effective smoke screen that enables them to keep their posts as ostensible professors of Christian origins and leaders of the church.

But we are not obliged to follow “cleverly devised tales” (2 Peter 1:16). The canonical Gospels exist. Q does not. The heretical, second-century Gospel of Thomas is not binding except on gnostics! On both historical and theological grounds, there is no reason to give up the canonical Gospels as the original and divinely inspired foundation for our faith.

The author and editors wish to thank translator Robert W. Yarbrough, associate professor of New Testament studies at Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri, for his editorial assistance on this article.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Marcus Borg, “What Did Jesus Really Say?” BR 05:05, and Robert J. Miller, “The Gospels that Didn’t Make the Cut,” BR 09:04.

This number is rounded off slightly. My comparison assigns 130 passages—65 from Matthew and 65 from Luke—into one of four percentage categories: 1–24.9%, 25%–49.9%, 50%–74.9%, or 75–100%. Matthew 6:9–13 (the Lord’s Prayer), for example, shares 26 identical words with its counterpart in Luke 11:1–4. These 26 words are 43% of Matthew’s total of 61 words, but 59% of Luke’s total of 44 words. In this case the two parallel passages fit into different percentage categories. This pattern repeats itself in about a dozen of the 65 pairs. That is why we get 53 passages (out of the 130), an odd number, in the 25–49.9% category, and 29 passages (out of the 130) in the 50–74.9% category. These have been rounded to 26 out of 65 pairs of parallel passages and 15 out 65 parallel passages, respectively. Despite this complication we still get an accurate picture of the overall verbal correspondence between Matthean and Lucan passages alleged to reflect the common Q source. The numbers show that, overall, the correspondence is hardly overwhelming.

Endnotes

An Introduction to the Study of the Gospels, 7th ed. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1888). Westcott comments (p. xii): “My obligations to the leaders of the extreme German schools are very considerable, though I can rarely accept any of their conclusions.”

Siegfried Schulz, Griechisch-deutsche Synopse der Q-Überlieferungen (Zürich: Theologischer Verlag, 1972), p. 5f.

Helmut Koester, Entwicklungslinien durch die Welt des frühen Christentums (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr [Paul Siebeck], 1971).

James M. Robinson, “The Sayings of Jesus: ‘Q’,” Drew Gateway (Fall 1983); Helmut Koester, Ancient Christian Gospels: Their History and Development (Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1990); John Kloppenborg, The Formation of Q (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987); Arland Jacobsen, The First Gospel (Missoula: Polebridge, 1992); Burton Mack, Q—The Lost Gospel (San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco, 1993).

Stephen J. Patterson, “Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05. Subsequent references to this article will be given as BR.

See Craig Blomberg, “Where Do We Start Studying Jesus?” in Jesus Under Fire, Michael J. Wilkins and J. P. Moreland, eds. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1995), pp. 17–50, esp. 19–25.

“Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05, quoting Mack, 8, 10.

“Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05.

“Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05 (Patterson quoting Mack, 4f.).

Arland Jacobsen, The First Gospel, p. 4, as cited in “Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05.

See, for example, Hans Herbert Stoldt, History and Criticism of the Marcan Hypothesis (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1980), p. 48.

G. Kittel,

See Eta Linnemann, Is There a Synoptic Problem? Rethinking the Literary Dependence of the First Three Gospels, trans. by Robert W. Yarbrough (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1992), pp. 68–70.

In the analysis below I follow the methodology of my book cited in the previous note. To avoid defining Q myself, I follow the Griechisch-deutsche Synopse der Q-Überlieferungen, corrected only as needed to conform to the text of Aland’s Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum, 11th edition.

John Wenham, Redating Matthew, Mark and Luke: A Fresh Assault on the Synoptic Problem (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1991), p. 54.

Linnemann, Synoptic Problem? pp. 185–191; fuller discussion and citations in D.A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1992), pp. 66–74, 92–95, 113–115, 138–157.

“Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05.

“Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05.

“Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05.

William R. Farmer, The Gospel of Jesus: The Pastoral Relevance of the Synoptic Problem (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 1994), p. 3f.

“Q—The Lost Gospel,” BR 09:05.