Is This King David’s Tomb?

Footnotes

This was not always so. Many prominent scholars (in the past) have concurred with the conclusion suggested here, that the tombs discussed below belong to the kings of Judah. These scholars include Raymond Weill, who excavated these tombs and first proposed this identification. Even quite recently Benjamin Mazar has written flatly that “the tombs of David (1 Kings 2:10), Solomon (1 Kings 11:43) and several of their descendants were cut into bedrock in the City of David,” although he later qualifies this by saying that “there is nothing conclusive that can be said one way or the other about the tombs, which Weill identified as belonging to the royal cemetery. The question, at least for the present, must remain open” (The Mountain of the Lord [New York: Doubleday, 1975], pp. 183, 185). See also Benjamin Mazar, Qadmoniot 1 (1968), pp. 11–12 (in Hebrew).

The more prevalent attitude today, however, is reflected in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, vol. 2 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Carta, 1993), p. 712, s.v. “Jerusalem”: “Weill ascribed these tombs to the kings of Judah, and at the time his opinion was shared by other scholars. Today, however, it is no longer accepted, especially since no other evidence has been found to confirm that they belong to the Israelite period.” On the latter point, see below.

The Anchor Bible Dictionary (ABD), vol. 2 (New York: Doubleday, 1992), p. 64, s.v. “David, City of,” takes a similar position: “Although many authors accepted Weill’s identification, scholarly consensus has rejected it on the grounds that no chronological evidence has been found linking these rock cuttings to the Iron Age. … Moreover, typologically, no such tomb plan is known from the Iron Age.” Both of these points are addressed below.

The ABD’s article on “Burials” discusses the tombs east of the City of David in Silwan and north in the École Biblique, and also notes that the Bible tells us that the early kings of Judah, including David and Solomon, were buried in the City of David, but does not even mention the existence of the tombs uncovered by Weill.

The ashes of the red heifer were used in a potion to purify those who had been defiled by contact with a corpse (Numbers 19; see also Leviticus 21:1–4, 11, 22:4–7; Numbers 5:2, 6:6–13, 9:6).

The Mishnah is explicit: Burial in towns surrounded by a wall is forbidden. Kelim 1.7. See Saul Lieberman, Tosefeth Rishonim, vol. 2, (Jerusalem, 1938), p. 135, and vol. 3, (Jerusalem, 1939), pp. 190–191. In the Dead Sea Scroll known as the Temple Scroll, the prohibition is implicit, but unmistakable. See Yigael Yadin, The Temple Scroll, (Jerusalem, 1983), vol. 2, col. 48, 11–14, p. 209; vol. 1, pp. 322–323. I am indebted to Professor Jacob Milgrom for these references.

Some kings of Israel were also buried in their respective capitals, for example, Baasha in Tirzah (1 Kings 16:6); Omri and Ahab in Samaria (1 Kings 16:28; 22:37). See also Shmuel Yeivin, “The Sepulchers of the Kings of the House of David,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 27, p. 30 (1948) (“Beginning at the latest with the thirteenth-twelfth century B.C.E. and at least down to the seventh-sixth century, it was the current custom in the whole East Mediterranean basin to bury the kings in their palaces, or in the near vicinity—at any rate, not only within the walls of their capitals, but apparently within the area of the inner citadels of such capital cities,” at p. 38).

According to the Bible, David “was buried in the City of David” (1 Kings 2:10); Solomon “was buried in the city of his father David” (1 Kings 11:43; 2 Chronicles 9:31); and Rehoboam “was buried with his fathers in the City of David” (1 Kings 14:31; 2 Chronicles 12:16). Likewise, Abijam/Abijah (1 Kings 15:8; 2 Chronicles 13:2–3), Asa (1 Kings 15:24; 2 Chronicles 16:14), Jehoshaphat (1 Kings 22:51; 2 Chronicles 21:1), Joram (2 Kings 8:24; the notice in 2 Chronicles states that, although Joram was buried in the City of David, it “was not in the tomb of the kings”), Ahaziah (2 Kings 9:28), Joash (2 Kings 13:1; as with Joram, although he was buried in the City of David, he “was not buried in the tombs of the kings” 2 Chronicles 24:25), Amaziah (2 Kings 14:20; in 2 Chronicles 25:28 in the Masoretic text, it says “City of Judah” instead of “City of David”; other witnesses have “City of David”; see, e.g., NRSV, REB, NJB), Azariah/Uzziah (2 Kings 15:7; in 2 Chronicles 26:23, it says “in the burial field of the kings”; some translations read beside or in the field adjoining, since Uzziah was a leper), Jotham (2 Kings 15:38; 2 Chronicles 27:9), Ahaz (2 Kings 16:20; cf. 2 Chronicles 28:27: Ahaz “was buried in the city, in Jerusalem; his body was not brought to the tombs of the kings of Israel”). In 2 Chronicles 32:33, Hezekiah is said to have been buried “on the upper part of the tombs of the sons of David.”

The burial of later kings is often noted, but is never located in the City of David.

These slots may be much later, however. Evidence of a combed instrument suggests they may be Byzantine, but this does not detract from the fact that the chamber was originally a tenth-century B.C.E. tomb.

See “The Tombs of Silwan,” BAR 20:03; Gabriel Barkay and Amos Kloner, “Jerusalem Tombs From the Days of the First Temple,” BAR 12:02; Gabriel Barkay, “The Divine Name Found in Jerusalem,” BAR 09:02.

David Ussishkin, The Village of Silwan (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1993), pp. 298–299.

Ussishkin referred me to Pierre Montet, Byblos et l’Egypte (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1928). Tomb V of this royal cemetery contained the famous Ahiram sarcophagus. The grave goods in these tombs were extraordinary, both in quality and number. For the plan of Tomb V, see planche CXXV of the Atlas. For the quality of the masonry of these tombs, see, for example, the engraving on p. 19 of the text and planches XX, LXXVIII–LXXXVII of the Atlas. The extraordinary grave goods are shown on the plates that follow.

On Tanis, see Pierre Montet, Le Drame D’Avaris (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1941), especially p. 164, fig. 47 and planche I.

Kathleen Kenyon, Digging Up Jerusalem (New York: Praeger, 1974), p. 156. In her effort to discredit these tombs as the royal cemetery, Kenyon even doubted that the Bible really meant “in” when it referred to royal burials in the City of David: “I would even go so far as saying that I doubt that in Jerusalem means within the walls of the city, for burial within the walls of the town was completely contrary to semitic practice” (p. 32). That’s why she had to argue they were cisterns.

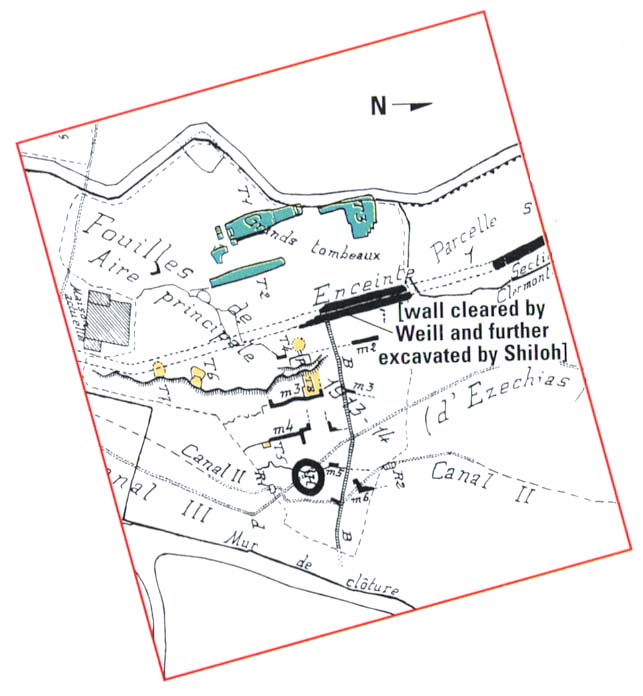

Loci W151 and W152 can be seen on figure 9, p. 47 of Shiloh, Excavations at the City of David. This wall can be fixed in a larger geographical context by identifying it on figure 3, p. 40, where T1, T2 and T3 are marked. East of T3, W151 and W152 can be seen in outline. A photograph of this city wall may be seen in plate 11:2.