The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) recently formed a committee to decide whether the James ossuary inscription and the Yehoash (or Jehoash) inscription are authentic or forgeries. I readily acknowledge the difficulty of the committee’s task. I also acknowledge the quality of the research and publications by my colleagues, some of whom I have known for decades. I therefore hesitate to comment on the work of the IAA committee, but its conclusions, announced at a widely publicized press conference, are at variance with my own conclusions regarding the inscription on the James ossuary.a (I shall not address the question of the Yehoash inscription.) If I kept silent, people would think that I am convinced by the IAA committee or that I simply do not want to take into account their position—which is not the case.

Therefore I have no choice but to critically assess the committee’s work. After all, that is what the committee members presumably did with my own research into the ossuary inscription—although there is not a single mention of my findings by any of the committee members.

The final committee reportb—really only statements of the committee members; there is no final report of the committee as a whole—begins by setting forth the convening authority’s guidelines for the committee members. These are indeed laudable, for they stipulate that committee members are “to arrive at the truth based on pure research only—without taking into account any other related factors regarding the collector, current gossip, rumors, or prejudices.” (Italics supplied.) Furthermore, “Each scholar is to work in his[/her] own discipline.” (Italics supplied.)

It was also anticipated that “The exact location and size of the sample would be precisely documented.” (Italics supplied.)

Finally, “Each committee member was given up to three months to submit a final report summarizing his/her opinion and reasons for their conclusions.” (Italics supplied.)

How closely did the committee members follow these instructions?

Before considering this question, I will make a few remarks about the choice of committee members. One can always complain that this or that person was chosen or not chosen. For me, the selection is not very important if, but only if, the persons chosen provide a detailed scientific report that can be reviewed by colleagues.

I can also understand the convening authority’s decision to appoint certain members “even if [as the introduction to the “Final Report” states] they had, in the past, expressed an opinion on the subject.” What is disturbing, however, is that apparently only people who expressed their opinion against the authenticity of the inscriptions were chosen and that no mention was made of the previous materials examinations by the Geological Survey of Israel (Jerusalem) researchers and the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto) curators.

The IAA committee consisted of two different committees—the Writing and Content Committee and the Materials Committee. The content committee was divided into two subcommittees—one for each of the inscriptions. Strangely enough, the subcommittee on the ossuary inscription did not include any paleographer or epigrapher. In contrast, the Yehoash subcommittee included “authorities on the First Temple period—archaeologists, linguists, historians, paleographers, epigraphers who would study the Yehoash inscription.” But the subcommittee on the ossuary inscription “consist[ed] of archaeologists, [and] Second Temple period linguistic scholars who would study the inscription.” Is the omission of paleographers and epigraphers (specialists in analyzing and dating scripts) from this latter subcommittee accidental? Or is there simply a printing error in the report?

Two other preliminary oddities (and then I will get to substance):

The introduction to the report notes that “If the pieces are authentic (particularly the Yehoash inscription), then they are of great scientific value.” (Italics supplied.) Is the James ossuary inscription—“James, the son of Joseph, the brother of Jesus”—not of such great scientific value as compared with the Yehoash inscription? What are we supposed to infer from this?

Secondly, there is also a danger in having a single materials committee deal with both the ossuary inscription and the Yehoash inscription. (This is in contrast to the content committee, which included two separate subcommittees.) The danger is that a factor that applies only to one of the inscriptions will affect the judgment of the committee regarding the other. For example, the report refers to the “almost simultaneous discovery” of the two objects. The fact is that they were not “almost simultaneously discover[ed]”; they were almost simultaneously published—the ossuary inscription in BAR late in 2002 and the Yehoash inscription in early 2003.c Their discoveries were decades apart.

Now let me turn to the individual statements—which constitute the final report—submitted by the members of the content subcommittee for the ossuary inscription and by the materials committee.

There were four members of the ossuary Writing and Content subcommittee.

Professor Amos Kloner is identified as an “archaeologist, [an] expert on burials and burial customs during the Second Temple period [in] Jerusalem.” He states that, to him, “the inscription looks new.” This is enough for him to conclude that it is a forgery. He also states that the forger worked “using contemporary examples.” He simply jumps to this negative conclusion without explanation or argument.

Actually, the fact that an inscription looks new is not really a problem for an experienced epigrapher who sees many inscriptions, some in bad—very bad—condition and some in good—even very good—condition. For example, take the famous Tel Dan inscription, excavated by Israeli archaeologist Avraham Biran. It is in excellent condition and has great historical value (it contains an extra-Biblical mention of David). Using Professor Kloner’s criterion, we would have to declare it a forgery. (So much for the “it’s too good to be true” argument.) Indeed, Professor Giovanni Garbini has declared the Tel Dan inscription a forgery,1 as have members of the so-called Scandinavian school of Biblical studies.2 Does Professor Kloner agree with their judgment?

Professor Kloner also makes a surprising historical assertion. He says that “the family of Jesus and James had no burial cave in first-century Jerusalem.” This was probably true when Jesus died in about 30 A.D., but we do not know what the situation was 30 years later, in 62 A.D., when James died. From the New Testament (which is our main source) it seems that Jesus’ family did not return to Nazareth, but instead stayed in Jerusalem after the crucifixion. This is quite clear regarding James himself and seems probable for Jesus’ mother, Mary, and his other brothers (Acts 1:14). After Jesus’ death, leaders of the Christian community seem to have consorted with Jesus’ family.3 Later tradition located Mary’s tomb in Jerusalem. So there is really no basis for Professor Kloner’s assertion; indeed, it might reveal a certain failure to appreciate the history of early Christianity.

Of course this entire discussion in Professor Kloner’s statement is gratuitous because it has no bearing on whether the inscription is authentic. That problem remains the same whether James was buried in a family tomb or in another tomb.

Dr. Tal Ilan is identified as a “historian, expert on the Hebrew and Aramaic names in the Second Temple period.” But she is not an epigrapher or paleographer. She specifically states this, acknowledging immediately that she is not “an expert on…carved inscriptions, or paleography.” Therefore, she says, on the question of the authenticity of the inscription, she will rely on what “experts have determined.” She does not identify these experts, however. (From the opinion she espouses, one can only guess that she relies on the “expertise” of one Rochelle Altman, who is not a serious scholar of Second Temple period paleography, but who early on in this controversy gained momentary fame by declaring the inscription to have been forged by two different hands.)

Although the committee’s guidelines instructed Dr. Ilan to work “in her own discipline” and although she admits she is not a paleographer, she nevertheless opined on matters of epigraphy. “The second part [of the inscription] seems scratched out in more cursive script…[This] may suggest that the reference to the brother could have been added later.” Oddly, this would contradict colleagues on the committee who say that the last part of the inscription may be authentic and that the forger added only the first part—as she herself proposed later on (see below).

Dr. Ilan also tells us, “In the summer of 2002, before BAR published its ossuary sensation, I had the opportunity to observe and photograph the [ossuary] inscription. The letters were clear and their context did not raise in me any special interest. The names were plausible.” From this brief mention, it appears that at that time the inscription looked authentic to her.

Quite inappropriately, Dr. Ilan reproaches Christian scholars in general—incidentally, the committee included not a single Christian and no New Testament scholar of any faith. Dr. Ilan remarks: “Christian scholars will always be interested in artifacts from the period of early Christianity, using these finds to blow out of all proportion their Christian religious relevance in an attempt to prove (or disprove) the truth of that religion.” This would seem to reveal a prejudice that contravenes the committee’s guidelines calling for members to base their conclusions on “pure research only—without taking into account any…prejudices.” (On this subject, see also the “joke” Dr. Ilan makes about Jesus’ words, discussed below.)

Apparently assuming that Christian scholars have overblown the significance of the inscription, even if it is authentic, Dr. Ilan tells us that “even if the ossuary [inscription] is authentic, there is no reason to assume that the deceased is actually the brother of Jesus (the first Christian).”

Dr. Ilan notes that Professor Camil Fuchs, head of the statistics department at Tel Aviv University, made a statistical study based on the appearance of the three names in the inscription—James, Joseph and Jesus, in their specific relationship—assessing the likelihood that the reference would be to the people mentioned in the New Testament. In general, Dr. Ilan approves of his study. But while Professor Fuchs found that probably 1.71 people named James in first-century A.D. Jerusalem might be described as son of Joseph and brother of Jesus, Dr. Ilan raises the figure to ten. But it is not clear on what basis she does this.4 She gives no explanation or calculation to support her new figure. This is hardly scientific and in fact reveals her prejudice.

Moreover, in her criticism of the identification of the ossuary as that of the New Testament James, Dr. Ilan fails to consider the second step in the identification. It is not merely the statistics, but the fact that the deceased’s brother is named on the ossuary. A brother is mentioned on only one other known ossuary inscription.5 This important datum is totally missing from Dr. Ilan’s analysis.

Turning to the area of her own expertise—ancient Hebrew and Aramaic names—Dr. Ilan detects a forgery in the misspellings she sees in the names on the ossuary. Both Joseph and James, she says, are misspelled. In the inscription Joseph is spelled YWSP. Dr. Ilan claims that “during the Second Temple period the name Joseph was always written as Jehoseph [YHWSP].” (Italics supplied.)

In her own book, however, she expresses herself differently: “During the Second Temple period the name YWSP was almost universally spelt YHWSP.”6 (Italics supplied.)

But even this is expressed too strongly. In more than 10 percent of other inscriptions, the James ossuary’s spelling YWSP occurs.7 For Dr. Ilan, however, the spelling of Joseph on the ossuary is “very rare and raises doubt about its authenticity.” This conclusion is not justified by the facts. We cannot say that a phenomenon is “very rare” when it occurs in more than 10 percent of cases. If Dr. Ilan’s argument were applied to all other inscriptions, more than 10 percent would be declared forgeries—or at least be considered suspicious.

She errs just as badly, or worse, with the name James. It is spelled Y’QWB in the ossuary inscription. Dr. Ilan claims that “the spelling Y’QWB, with vav, was found on two ostraca at Masada but never on any papyrus or ossuary of the period.” But this is an error, one that is repeated in her book.8 If she had simply looked at the concordance in Rahmani’s catalogue,9 she would have seen that, out of the five occurrences of this name on ossuaries, three, a majority, are spelled Y’QWB, as on the James ossuary.10 The situation is precisely the opposite of what Dr. Ilan wrote in her committee statement (and published in her book). The spelling on the James ossuary is more frequent on ossuaries than the alternative spelling.

Dr. Ilan presents an interesting reconstruction of what the alleged forger did. Based on what two other committee members (Dr. Orna Cohen and Dr. Avner Ayalon) wrote—that original ancient patina was found in the second half of the inscription (Cohen) and in the last letter of the inscription (Ayalon)—Dr. Ilan “suggest[s] that the forger came into possession of an ossuary bearing an authentic inscription ’brother of Jesus’…Such an ossuary could easily fire the imagination of a forger, who added the name of the brother of Jesus Christ to the ossuary to raise its value.” This suggestion is based on Dr. Ilan’s notation that “All the epigraphists have already concluded that the hand which inscribed the words ’James son of Joseph’ is not the same one as that which inscribed the words ’brother of Jesus.’” (Italics supplied.) Without specifying who “all the epigraphists” are, we can only guess that Dr. Ilan is referring to the opinion of Rochelle Altman, already mentioned. For Dr. Ilan, I obviously do not count as an epigraphist, nor do Professor Frank Cross of Harvard, Father Joseph Fitzmyer formerly of the Catholic University of America, Dr. Ada Yardeni (author of The Book of Hebrew Script) and Joseph Milik, a prominent Dead Sea Scrolls epigrapher—all of whom see only one hand in this inscription. So much for “all the epigraphists.”

In the last paragraph of her statement, Dr. Ilan tells us she “would like to end with a joke.” Readers may need some background information to understand this joke, so here it is: For the brother of the deceased to be mentioned on an ossuary is highly unusual. One possible explanation would be that the brother was responsible for the burial. Of course, this explanation cannot apply in James’s case, because Jesus was already dead when James was killed—unless the resurrected Jesus buried his brother.

This is what Dr. Ilan makes a joke of. What if (she says) the resurrected Jesus really was responsible for the burial? Jesus, Dr. Ilan “jokes,” would thereby be proving his own words in Matthew 8:22: “Let the dead bury the dead.” In this way, Dr. Ilan concludes, we would be “allowing Jesus to live up to his own principles.” Some joke!

Professor Ronny Reich is designated in the report as an “archaeologist—[an] expert on [the] First and Second Temple periods.” Professor Reich examined the inscription “with naked eyes,” and did not find any difference in the hands of the inscription (in contrast to Dr. Ilan). He noticed that the engraver carved the letters with the aid of a ruler and carved them “from the ruler downward…[the] same method as Second Temple period scribes.” Whoever wrote the inscription, he says, was a speaker of Aramaic. Insightfully, Professor Reich noted that “if the inscription had read ’Yosef [Joseph] son of Ya’acov [James] brother of Yeshua [Jesus],’ no one would have raised an eyebrow, and the inscription would have quietly entered the statistical lists without a further thought.” Professor Reich is almost certainly right on this point. All this attention—and suspicion—is attributable to the fact that New Testament figures may be mentioned.

As to the authenticity of the inscription, Reich concludes: “It appears that each of the characteristics of the inscription, as detailed above, and all of them together, with no exception, indicate an authentic late Second Temple period (mainly first century C.E.) inscription.” Nevertheless, he decided the inscription is a forgery because of the findings of the materials committee, whose scientific examination concluded that the coating or patina on the inscription was “produced and placed inside the letters in an artificial manner and could not have been produced in nature in ancient times…As a result, I am forced to change my opinion on the matter.” He does not use the word fake or forgery. Neither does he discuss the possibility that this particular patina could have been the result of modern cleaning of the ossuary. More on this later.

Professor Reich finds that the inscription is not very important “if we overlook the religious feelings (that could arise among Christians today) evoked by this inscription.” Apart from these, however, he continues, “its significance for the study of Jewish society at the close of the Second Temple period is slight. The inscription does not add any new onomastic or prosopographic data.”

Does the inscription have historic significance or is its significance slight? True, Jesus and James are already well known from the New Testament and from Josephus, as well as from early Christian tradition. But, still, if the inscription is authentic and the identification is accepted, this is the first clear case of a Christian Jew (or, more correctly, a Nazarene; see Acts 24:5) being buried according to common Jewish custom. It is also archaeological confirmation that Aramaic was used by this group, and it is the earliest epigraphical attestation of Jesus of Nazareth.

Most Jewish scholars seem to treat James as if he were not Jewish. But Nazarenes (Christian Jews) were still considered Jews at least as late as 70 A.D., when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and the Temple. To consider the Nazarenes as non-Jews before the Roman destruction is an anachronism. It would be like saying that the Essenes, who were responsible for the sectarian documents among the Dead Sea Scrolls, were also not Jews. But no scholar takes that position.

The inscription also has significance in reflecting the diversity of Judaism at the close of the Second Temple period and in revealing the Jewish roots of Christianity.

Professor Reich considered three possible reasons for naming the brother in this ossuary inscription. He did not consider a fourth—namely, that “brother of Jesus” was a kind of nickname used of James during his lifetime. This is a distinct possibility attested by the literary tradition (Josephus and New Testament).

Dr. Esther Eshel, an “expert on the history and development of Hebrew script,” gives a brief report—of less than a page. She states her opinion that “the inscription is not authentic, and was added later to the original ossuary (possibly in two stages).” She offers several reasons for this conclusion.

Dr. Eshel says she is not aware of any ossuary “where the letters are so deeply engraved and the decoration on the same ossuary [three rosettes faintly visible on the opposite side of the ossuary]…so worn as in the ossuary before us.” For this, she cites Rahmani’s catalogue. But this catalogue is not complete. And some of the ossuaries in the catalogue are not illustrated. Most important, in several cases cited by Rahmani the inscription clearly appears to have been incised more deeply than the decoration.11 Moreover, the James ossuary inscription is certainly not the only case where the erosion and encrustation on the side with an inscription seems different from that on the other side.12 Sometimes there is even a difference on the same side of the ossuary.13 For an ossuary where the decoration is worn and the inscription on the other side is clear and deep, see No. 62, plate 10, in Rahmani’s catalogue. Should we therefore declare this a forgery?

That the James ossuary may have been reused after the rosette decoration had faded is a possibility, but this suggestion seems unnecessary to explain the contrast between the rosettes on one side and the inscription on the other.

Dr. Eshel also finds that the inscription was made by “two different chisels”—so, she says, “I have been told” by committee members who gave the inscription “a very precise examination.” Not only is this contradicted by Professors Kloner and Reich, who hold a different opinion, but the experts on whom she relies are not identified. Here again is a case where, contrary to the IAA guidelines, an “expert” improperly adopts others’ arguments, thereby contravening the guideline that each committee member is to write “in his [or her] own discipline.”

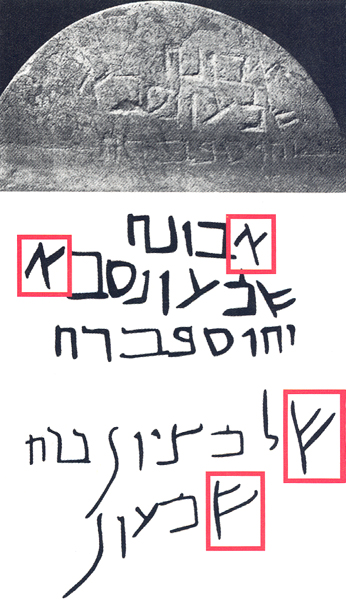

Actually, the “variations in handwriting, thickness and depth of the incised letters,” which Dr. Eshel finds suspicious, are exactly what can be expected on an inscription that was not incised mechanically or according to a printed model. If “variations in handwriting, thickness and depth” were the criteria, we would have to declare numerous inscriptions in Rahmani’s catalogue to be forgeries. For example, in No. 12, plate 2, the two alefs are different; in No. 26, the shins are different (drawing opposite, bottom). In No. 35, the depth of the letters seems different.

If there were no variations in the shapes of the letters and their thickness and depth, if all the letters were exactly the same shape and the same height and the same depth, then it would probably be a fake! This would mean that the inscription had been made mechanically or with a printed or computerized model.

Dr. Eshel also makes a paleographic argument: “There is a significant difference between handwritings in the first and second parts of the inscription. The first part is written in the formal style of a scribe and the second part is cursive.” In a footnote, I discuss each letter in the 20-letter inscription, as to whether it is formal or cursive.14 This examination shows that formal and cursive are all mixed together—as is not uncommon in ossuary inscriptions. Using F for “formal” and C for “cursive,” this is how the letters of the inscription break down: CFFCFFFCCFFCFCCCCFCF.

In short, we have a mixture of formal and cursive shapes in this inscription. It is incorrect to say that one part is formal script and the other is cursive script. Moreover, the mixture of formal and cursive letters is a well-known fact, underlined several times by expert commentators. In a footnote I quote a number of experts on this common phenomenon.15

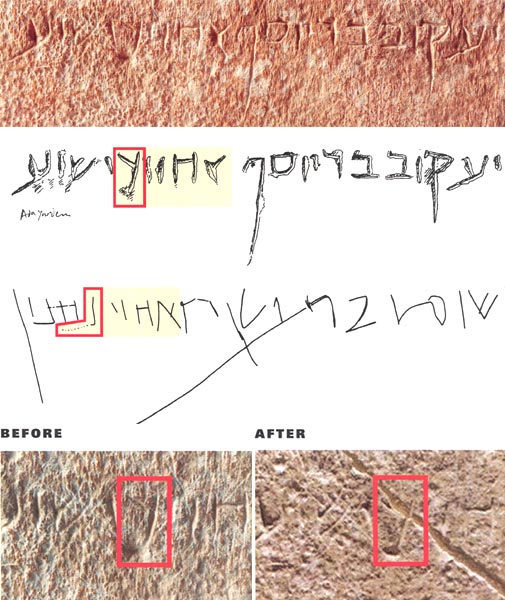

Dr. Eshel’s final argument is that the forger copied the word “brother of” (’HWY D) from the only other appearance of this word on an ossuary. She observes, “When comparing the words ’brother of Jesus’ on this ossuary to ossuary No. 570 [in Rahmani’s catalogue]…a surprising resemblance can be seen. The letters [in achui, ’brother’] het, vav, and yud are quite similar, and the most exceptional letter dalet is identical. In both inscriptions, only the descending line [of the dalet] survived. It thus seems that the writer copied the inscriptions from this [other] ossuary.”

I invite readers to make this comparison for themselves. Look carefully and you will see that on ossuary no. 570, the second, third and fourth letters of “brother” (reading right to left, het, vav and yod) slope down on the right, while in the James ossuary inscription, they are clearly vertical.

The fifth letter (dalet) appears as a descending line on the other ossuary, as well as on recent pictures of the James ossuary. This shape of the dalet is anomalous and that such a close duplicate is found on the James ossuary would ordinarily arouse suspicion. However, this problem exists only if you use a picture of the James ossuary taken after it had cracked on the trip from Israel to Toronto for exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum. One of the cracks went right through the inscription—indeed, through this dalet. When the ossuary was restored, part of the dalet disappeared, namely the top left stroke of the letter. This stroke is clearly visible, however, in the pictures taken before the crack.

So the argument that the alleged forger “copied the inscriptions from this [other] ossuary,” as Dr. Eshel contends, is baseless.

In short, the James ossuary inscription does not raise any paleographic, linguistic or orthographic (spelling) problems, and there is no reason on these grounds to cast doubt on its authenticity. This is underlined by Dr. Reich’s initial conclusion: All signs point to a Second Temple period date. Clearly that was also the reaction of Dr. Ilan when she first saw the inscription; she raised no question as to its authenticity until I suggested the identity of the deceased (James) in my BAR article. Clearly it is not the inscription itself that raises problems but the identification of the deceased with a historical personage mentioned in Christian tradition. The easiest and simplest way to reject this interpretation is to cast doubt on the authenticity of the inscription.

The tendency to cast doubt on Northwest Semitic inscriptions is not new. The same thing was done with the Mesha Stele, discovered in 1868, which contained the first mention of the God of Israel and of an Israelite king, Omri. Several articles were published in scholarly reviews that cast doubt on its authenticity, the last one as late as the 1940s.16 In 1993, the discovery of the Tel Dan inscription with its reference to BYT DWD, “House of David,” was followed by several articles in scholarly journals, some of which doubted David’s existence and proposed a different interpretation of these letters. Professor Giovanni Garbini questioned the authenticity of the inscription because it seemed “too good to be true.” Russell Gmirkin continues the debate in a journal published in Sweden.17

Let us now turn to the work of the materials committee. I am not myself an expert in the fields of geology and isotopes of oxygen, so I cannot comment from the viewpoint of a scientist who knows these fields. But apparently even an expert would not be able to comment because, as the two scientists who wrote relevant statements on these aspects of the ossuary inscription admit, their report is not final, as I previously noted. They say they will write a final report sometime in the future and publish it in a professional journal. Until that time, however, scientific comment is well-nigh impossible. My own comments, however, are based on common sense. Do the statements filed by the committee members make sense? You be the judge.

Two of the five committee members filed very short statements. Dr. Elisabetta Boaretto is an expert in carbon-14 dating, a test that can be applied only to organic materials. Since there are none on the ossuary, her expertise is not particularly relevant, as she recognizes. The statement of Jacques Neguer, an expert in antiquities conservation and restoration, is only 11 lines long. He makes no argument that is not presented in the other statements, which I treat elsewhere.

Dr. Orna Cohen is a conservator, “specializing in identification and restoration of ancient patina.” She describes three factors that lead her to conclude that the inscription only “suggests forgery.” (Italics supplied.) This seems to mean that she is not sure the inscription is a forgery.

The first factor she cites is that “the patina in the letters is grainy…not similar to natural patina.” How did this patina get there? According to Dr. Cohen, “It appears that ground chalk mixed with water was used to coat the letters.” She then jumps on an evil motive without considering whether other, less nefarious, reasons may explain this grainy patina—perhaps it was the accidental result of a cleaning.

Why is this grainy patina here? Dr. Cohen guesses, “Probably to camouflage the intervention of the inscription.” (Italics supplied.) Again, she is not sure. But she assumes the worst (to camouflage a forgery), without considering other, more benign, possibilities.

Then she drops a bomb. She finds that the same yellowish patina that is on the side of the ossuary is also in the incisions of the letters of “brother of Jesus.” Her exact words are: “A microscopic examination revealed the same yellowish patina as on the ossuary surface inside the letters ’brother of Jesus.’” If I understand this correctly, it means that she finds the last two words of the inscription to be authentic! And if the last two words are authentic, then, based on the paleographic, linguistic and orthographic considerations outlined above, the entire inscription is very probably authentic. Paleographical analysis shows that the entire inscription was engraved as a continuum. And linguistically it would be difficult to explain an ossuary that was inscribed only “brother of Jesus,” with nothing else, but waiting to be completed by a forger.

Dr. Cohen does not reach this conclusion, however. Instead, she finds that “even though part of the inscription may be original, the inscription in its entirety is a fake.” (Italics supplied.) This sentence is completely illogical and reveals her prejudices. How can one say, “Even though part of the inscription may be original, the inscription in its entirety is a fake”? In the same sentence, we have two statements that contradict each other!

This brings us to the two geological statements, which really form the basis for the IAA committee’s conclusion. Dr. Avner Ayalon, of the Israel Geological Survey, a geologist and an “expert on identification of materials through the study of isotopes in rock,” appears to have performed the tests, which were then analyzed by Professor Yuval Goren, an archaeologist who is also an “expert on petrography and identification of materials and sources.”

Both men specifically declare that their statements do not constitute a final report. Dr. Ayalon emphasizes at the outset that “this document does not constitute a scientific article or report.” Professor Goren states, “The following detailed summary is not a scientific article.” Therefore, unfortunately, it is impossible for other experts to review their work. It must be taken on faith, which apparently is what the other members of the committee did.

Dr. Ayalon took seven patina samples and tested them for the ratio of isotopes of oxygen of different weights. He finds that the patina in the last letter of the inscription seems old. But instead of concluding that there is no reason to doubt the authenticity of this letter, he tries to explain it as a testing mistake.

Moreover—a harbinger of things to come—Dr. Ayalon suggests in the next to last paragraph of his statement that the variations in the isotope ratio could be caused by water “at temperatures of 40–50 degrees centigrade.” Water boils at 100 degrees centigrade. Would it not be possible that an energetic cleaning with warm water (40–50 degrees centigrade), perhaps with soap or soap powder, could have created a patina with the isotope ratio he found? Dr. Ayalon does not explore this possibility.

This brings us to the Final Interpreter, Professor Goren. He lets the cat out of the bag, so to speak. He concedes that “the inscription was engraved (or at least, completely cleaned) in modern times.” (Italics supplied.) Why does he put the alternative in parentheses?

Elsewhere Goren explains that the person who created the coating applied it “in order to blur the freshly engraved signs.” How can he tell? Is there not another possible explanation—a rigorous cleaning with a brush and warm water?

Interestingly, in the first quotation above (with the “or”), Goren puts the possibility of cleaning in parentheses; in the later quotation (the coating was applied “in order to blur the freshly engraved sign”), the explanation of cleaning disappears altogether. The same phenomenon appears in his “Abstracts of Findings,” where he wrote first: “The inscription was inscribed or cleaned in a modern period,” but, later on, the alternative explanation of a cleaning is no longer considered.

In fact, we know that the ossuary was cleaned. Not only did the owner tell us of this possibility, but the GSI’s first examination also recognized this, as did the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) team, which found that it was cleaned with a sharp instrument to such an extent that some of the letters of the inscription were “enhanced.” Yet the ROM team found no reason to question the authenticity of the inscription. Most significant, however, only the first part of the inscription was thoroughly cleaned. This may well explain why the ancient patina remains in the letters in the second half of the inscription.

Let us look at what is probable—aside from the conjecture that the suspicious coating was a forger’s effort to conceal his dirty work.

The owner says that he bought the ossuary several decades ago from a Jerusalem antiquities dealer in the Old City. On the market, the price of an ossuary depends on the quality of its decoration and/or its inscription. An uninscribed, undecorated ossuary has very little value. Obviously, the seller wants to show off his goods to advantage, emphasizing the quality of the decoration and the clarity of the inscription. In this case, the decoration was so faint he may not even have noticed it. Even if he did, he could not argue that this significantly increased the ossuary’s value. The inscription, however, was a different matter. He very probably tried to clean it. How? With a brush, warm water and perhaps a nail to get inside the letters. In this way, the letters would look sharper. Admittedly, this is conjectural, but at least it is a plausible scenario.

Later, according to the owner, the ossuary was placed on the balcony of his parents’ apartment. The balcony was partially open and from time to time rain would come in and standard heating was sometimes used during the winter. Later on, the ossuary was on a balcony and in a small back room of his apartment and from time to time cleaned by maids.

Still later, the owner put the ossuary in storage, where it was when he first showed me a photograph of it. In the Tel Aviv area, it would have been in a much wetter atmosphere than in a Jerusalem cave—and also in a much warmer climate, with more variation in temperature.

The possibilities are better stated by Dr. Amos Bein, the director of the Israel Geological Survey, who told Canadian filmmaker Simcha Jacobovici quite specifically that the work Dr. Ayalon did for the Survey did not show that the inscription was a forgery. In Dr. Bein’s words:

“We didn’t decide the inscription is fake,” he said. “If somebody would like to preserve the inscription, or would like to improve its appearance, and he would like to clean it, and thereafter to make it shine better, and he made [a] procedure of cleaning, thereafter adding warm water and so on, he may have created some carbonate particles which may provide this isotopic composition.”

As between the two explanations—forgery or cleaning—the latter is consistent with the paleography and the linguistics, both of which indicate that the inscription is one continuum.

Surely, the explanation for the patina as a result of a modern cleaning (or cleanings) is at least plausible. In fact, this explanation has been espoused by two previous materials examinations, one by the Israel Geological Survey and the other by the ROM. Their studies, however, were not mentioned by the IAA committee.

For all these reasons, I’m afraid little confidence can be placed in the IAA’s conclusion on the ossuary.

A more detailed version of the paper was published in The Polish Journal of Biblical Research 5, December 2003.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

I published the inscription; see André Lemaire, “Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus,” BAR, November/December 2002.

Endnotes

Giovanni Garbini, “L’iscrizione aramaica de Tel Dan,” in Atti della accademia dei Lincei, Scienze morali, storiche filologiche, rendiconte (Rome, 1994), IX.V.3, pp. 461–471.

She gives as her reason: “The reservoir of names from which parents could have chosen their children’s names was small and therefore the chance of choosing these names was higher, and increased as other names were already taken in the family.”

I am not sure I understand what she is saying. In fact, Professor Fuchs did take this problem into account. He specifically stated: “It is important to note that, since we assume that no two brothers in the family bore the same name, the probability of a child being given a certain name depends on the name given to the previous born male offspring in the family.”

No. 570 in L.Y. Rahmani, A Catalogue of Jewish Ossuaries in the Collections of the State of Israel (Jerusalem: IAA, 1999).

Tal Ilan, Jewish Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity I, Palestine 330 B.C.E.-200 C.E. (Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2002), p. 17.

As she herself notes in her book, out of 32 attestations on ossuaries, two ossuaries (and three attestations) use the spelling YWSP (Rahmani catalogue No. 573, with two attestations, and Emile Puech, “Ossuaires inscrit d’une tombe du mont des Oliviers,” Liber Annuus 32 [1982], pp. 355–372, especially 358), i.e. about 10% of cases. She also rightly mentions the Beney Hazir inscription (CIJ 1394) with two attestations (D. Barag, “The 2000–2001 Exploration of the Tombs of Benei Hezir and Zachariah,” Israel Exploration Journal 53 (1993), pp. 98–110, especially 92), as well as papyrus Murabba’at nos. 28 and 31, Yadin papyrus no. 7 (three different personages, about ten attestations) and Yadin papyrus no. 44 (probably a mistake for Yadin papyrus 9.5), which makes at least seven instances (and more attestations) of this spelling, “compared to nearly 50 instances of ’Yehoseph’”: This would come to over 10%!

Two are written Y’QB (nos. 290, 865) and three Y’QWB (nos. 104, 396, 678; this spelling is confirmed by the drawings).

See also no. 446, pl. 62, where the lid presents erosion and encrustation while the other side looks brand new.

Yod (nos. 1, 8, 15, 17) is written as a simple, short, approximately vertical stroke without a small crook, hook or loop at the top; this shape is cursive.

’ayin (nos. 2 and 20) can be considered formal even if it appears sometimes in cursive script.

kuf (no. 3) is formal.

vav (nos. 4, 9, 14, 19) is a simple vertical stroke, longer than the yod, but also without a small crook, hook or loop at the top; this shape is cursive.

bet (nos. 5, 6) is formal.

resh (no. 7) is formal.

samek (no. 10) can be considered formal even if it appears sometimes in cursive script.

final pe (no. 11) can be considered as formal even if it appears sometimes in cursive.

alef (no. 12) is cursive.

het (no. 13) is formal.

dalet (no. 16) is cursive.

shin (no. 18) is formal.

J.T. Milik, “L’epigrafia offre un bell’esempio di scrittura mista: BNH è calligrafico ed il resto è cursivo” (in P.B. Bagatti and J.T. Milik, Gli scavi del “Dominus Flevit,” parte I. La necropoli del periodo romano (Jerusalem, 1958), p. 79 and passim. “The ossuary script in the Jericho inscriptions combines cursive and formal elements, resulting in different forms of the same letter, often appears [sic] together in a single inscription.” (Quoted from Rachel Hachlili, “The Goliath Family in Jericho. Funerary Inscriptions from a First Century A.D. Jewish Monumental Tomb,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 235 (1979), pp. 31–66, especially p. 60).

This phenomenon is also attested in the Greek ossuary inscriptions: “An interesting paleographic feature occurs in this inscription: the use of cursive letters side by side with lapidary forms; the alpha at the end of the word Kyria is cursive. The more common lapidary alpha also appears in this inscription—in the word kai…” (Tal Ilan, “The Ossuary and Sarcophagus Inscriptions,” in Gideon Avni and Zvi Greenhut, eds., The Akeldama Tombs. Three Burial Caves in the Kidron Valley, Jerusalem, IAA Report No. 1 [Jerusalem, 1996], pp. 57–72, especially p. 57).

A.S. Yahuda, “The Story of a Forgery and the Mesha Inscription,” Jewish Quarterly Review (JQR) 35 (1944), pp. 139–163. W.F. Albright’s prompt answer, “Is the Mesha Inscription a Forgery?” JQR 35 (1945), pp. 247–250, seems to have closed the debate.

See Russell Gmirkin,“Tools, Slippage and the Tel Dan Inscription,” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 16.2 (2002), pp. 293–302. The same charge was made earlier by Niels Peter Lemche in “Face to Face: Biblical Minimalists Meet Their Challengers,” BAR 23:04.