038

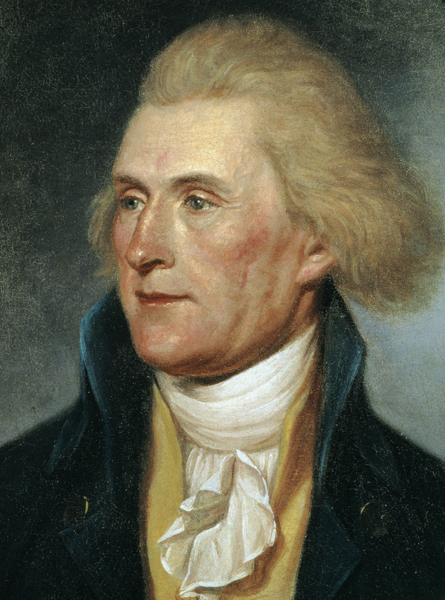

Among his many other accomplishments, the third president of the United States rewrote the Bible. That might seem a remarkably audacious thing for anyone to do, but it was quite natural for a man of Thomas Jefferson’s complex nature. He was a true genius who often got into trouble for refusing to follow the crowd. And he approached Holy Scripture with the same controversial attitude that drove all his actions.

In fact, Jefferson was at his most controversial when it came to religion. His arch rival, Alexander Hamilton, accused him of being an atheist, and in the heat of partisan politics, the story was repeated and magnified until most of the country believed it.

For his part, Jefferson declined to answer the charge. He never spoke publicly about his religious beliefs. Realizing that anything he said would only add fuel to the controversy, he refused to discuss his faith except with his most trusted friends, and even then he found it necessary to remind them to keep his words confidential.

Thomas Jefferson’s brushes with controversy were, of course, a product of his inquiring mind. Not one to accept the standard explanation for anything, he was always asking questions and energetically pursuing answers.

His interests were varied—science, philosophy, architecture, politics—and he wanted to understand the “how” and “why” of everything he encountered. This was a man who once said “I can not live without books” and who designed a portable desk so he wouldn’t have to interrupt his writing while he was on the road. When he built a home at Monticello, he was actively involved at every step, from drawing the plans to nailing the boards. And as a gentleman farmer, he ordered and inspected all his seed personally.

It was just this curiosity and desire for involvement that shaped his approach to religion. The young Jefferson had a traditional Protestant background, being raised in an Anglican family. But the 18th century was a time of changing attitudes. This was the time of the Enlightenment, when science first used modern methods and religion became a subject not just of faith but also of study.

In this setting, Jefferson drifted away from the doctrines he learned as a child. Although he continued to attend church throughout his life, he came to favor the Deism that was in vogue among the intellectuals of the day.

Deism was popular partly because it suited the new scientific age. Its proponents believed that the world was created by a personal God, and they were convinced the human soul was immortal, though they disagreed about whether God still influenced human affairs. They were united, however, in the conviction that he had given them an orderly world to live in. It operated according to scientific principles, and people were endowed with the ability to understand it.

In this way, Deism sidestepped the apparent conflict between science and religion. Both, it said, could be explored with the two methods fine-tuned during the Enlightenment—scientific observation and logical deduction.

These were methods Jefferson was equipped to employ to the fullest. Though remembered as a 040politician and statesman, he was also very much the scientist. And as such he was committed to learning through reason, observation and research.

As both a rationalist (believing that truth came from reason instead of revelation) and a materialist (preferring the world he could see to the spiritual realm he could not), he didn’t accept the Bible as it was handed down and interpreted by traditional theologians. Rejecting the doctrine of revealed truth, he saw religion as something to be analyzed logically. Yet he found the Bible stories so fascinating that he couldn’t leave them alone. And that tension led him to wonder how much of the Bible he could believe.

The New Testament was foremost in his mind, and that was what he decided to rewrite. When he finally finished the project, he would call it “The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.” The title indicates, with typical Jeffersonian insight, precisely what he was trying to accomplish. Jesus’ life fascinated him. But he was not satisfied with the way the Bible reported it. He preferred a very human Jesus, separated from the doctrines of virgin birth and resurrection. And the most important thing about that Jesus was his moral philosophy.

But trying to tease the philosophy he sought from the Bible was no trivial pursuit. It occupied Jefferson’s thoughts for nearly two decades.

The first step was simple enough. Some time in 1803, shortly after becoming the third president of the United States, he prepared a digest of Jesus’ teachings. These were the Master’s words, cut from a copy of the Bible and pasted on blank pages. They made a book of 46 pages, which he titled “Philosophy of Jesus” and from which he read nightly.

With a little effort, we can imagine the end of the president’s day. After sorting out the ever-present political problems and affairs of state, he sat alone in his bedroom, relaxing in the very seat of the nation’s power, trying to grasp the essence of the Bible and how it related to the people of his day.

This was, after all, the man who penned the Declaration of Independence at the age of 33 and was a strong proponent of “separation of church and state.” In his view, a wall had to stand between government and religion. But that wall was not intended to hold down the church. It was to protect each person’s right to worship as he or she chose.

Jefferson spent most of his life thinking about the individual’s right—and need—to be an individual. And editing the Bible was partly an outgrowth of that commitment to individual freedom. His enduring beliefs in liberty and the power of reason forced him to conclude that everyone had both the ability and the right to interpret the Bible personally.

The “Philosophy of Jesus” was an expression of those beliefs, but it was only a first, tentative effort. It did not accomplish everything Jefferson knew he could do with the subject. His goal was a more thorough study of Jesus’ doctrines, drawn from the original languages as well as modern translations and arranged in a way that made their meaning clear.

The “Philosophy” had been drawn only from the English translation, and it didn’t go far enough. Completing the project would require more Bibles and another round of cutting and pasting.

But Jefferson was worried about something else, too. He was convinced that the church fathers had consistently failed to understand Jesus’ moral teachings and were guilty of “expressing unintelligibly for others what they had not understood themselves.”

Worse, Jefferson believed that Jesus’ teachings were still being misunderstood. Most people simply accepted what they read in the Bible without questioning its accuracy. They didn’t examine the various statements and interpretations of Jesus’ doctrines to discover what he really said and meant.

That was the problem as Jefferson saw it, and his scientist’s mind saw the solution with crystal clarity. A scientist goes directly to the thing he wants to study. To understand a flower, he places one under a magnifying glass. To understand the stars, he gets a telescope and looks at the night sky.

Obviously, to understand Jesus’ teachings, it was necessary to go directly to his words. It was in those words that the best statement of the real Christian doctrine could be found, and they were recorded specifically in the four canonical Gospels.

It was no surprise, then, that Jefferson stated his intention to use only these Gospels. He excluded the Book of Acts and the epistles because they did not give direct evidence of Jesus’ thoughts.

Paring the New Testament down to the basic facts would remove any biases that had crept in during those formative years when the apostles were trying to make everything mesh with the doctrines of the early Church. But there was a limit to how far Jefferson could go and still remain faithful to his goal. Rewriting Jesus’ words would not do. That would merely add another round of commentary, precisely the problem he was trying to correct. 041He had to stick to the actual words of Jesus. And they had to reflect the historical context that produced them. This meant that the work had to describe Jesus’ life, not just his philosophy.

That posed another problem. Jefferson was convinced that the events of Jesus’ life, like his words, were concealed under layers of interpretation and commentary. To get to their essence, it would be necessary to pinpoint and remove everything that had been added after the fact.

Obviously that was going to be a daunting task, and Jefferson was reluctant to take the responsibility for it. He tried repeatedly to pass it off to close friends, including Joseph Priestley, the famous minister and scientist, but none were willing to take on such a task. Priestley might eventually have done it, but we will never know. His death in 1804 put the project back into Jefferson’s lap.

Realizing that he would have to do it himself, Jefferson finally set to work with characteristic thoroughness. He was sure that he could distinguish Jesus’ words from what other people thought he said, whether commentary or inauthentic words. And with his skill as a scientist, he had no doubt that he could discover the facts of the Master’s life. Once that was done, it only remained to arrange the texts in a more or less chronological order.

The result would be the essence of Jesus’ teachings—a core of truth and wisdom from which ordinary people could use their powers of reason to draw their own conclusions. As Jefferson expressed it, “There will be found remaining the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man.”

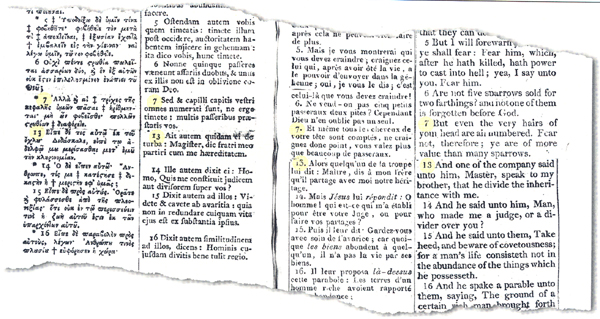

To get started, he ordered Bibles in English, French, Latin and Greek. Fortunately, he knew all these languages well and could make his way through the text in each of them.

The plan, as before, was to cut the pages out and paste them onto blank paper. But that meant he could use only one side of each page, so he needed two copies of each Bible.

About a dozen years after leaving the White House, and less than a decade before his death, Jefferson had the necessary books in hand and finally undertook the physical process of rearranging the New Testament. First, he cut out the material he 046wanted and laid out the verses “in a certain order of time or subject.” Then he marked out the passages that didn’t fit his objective, removing the accounts of Jesus’ miracles and the mysticism he believed had been added years after Jesus died, leaving only the words of Jesus and the basic facts of his life.

When all of that was finished, the former president held in his hands what is now known as the Jefferson Bible: four parallel columns—in four different languages—that embodied one man’s understanding of the moral philosophy that Jesus Christ gave to the world.

Though justifiably proud of the result, and though he had devoted years of time and energy to the project, Jefferson never published it. His religious views had been so misunderstood and so harshly criticized that in the end he knew better than to release a heavily edited version of the New Testament under his own name. Instead, he kept the volume to himself and told only his most trusted friends about it.

Not surprisingly, the book didn’t resurface until some years after his death in 1826. It was known to exist. At least, references in his correspondence showed that it once had existed. Historians hoped it still did, and they were encouraged by Jefferson’s commitment to learning. He was not the sort of man to destroy a book, especially one he considered so important.

The elusive volume finally did reappear near the turn of the century. And in a roundabout way, it made its way into the hands of the people for whom Jefferson composed it in the first place.

The United States government bought the book in 1895; they had no doubt that it belonged to the nation. In 1904 Congress published it under the title The Morals of Jesus and gave copies to its members. And commercial printings eventually appeared in bookstores, including editions in 1923, 1940 and 1989. So the book Thomas Jefferson once kept carefully hidden was finally available for anyone to see.

Now that his Bible is available, what are we to make of it? Despite of the rumors that always plagued him, Jefferson saw himself as a deeply religious man. He proudly said of his volume that “it is a document in proof that I am a real Christian, that is to say, a disciple of the doctrines of Jesus.”

How well he succeeded in communicating his faith is a matter of controversy. To this day, people debate the merits of the Jefferson Bible. Some say it is a marvelous expression of Jesus’ morality, offering a fresh insight into his teachings. Others say it is a naive attempt at Bible criticism and nothing more than a dated example of another age’s beliefs.

Perhaps, in the end, we must each draw our own conclusion. But Jefferson would have no objection to that. It’s what he had in mind all along.

Among his many other accomplishments, the third president of the United States rewrote the Bible. That might seem a remarkably audacious thing for anyone to do, but it was quite natural for a man of Thomas Jefferson’s complex nature. He was a true genius who often got into trouble for refusing to follow the crowd. And he approached Holy Scripture with the same controversial attitude that drove all his actions. In fact, Jefferson was at his most controversial when it came to religion. His arch rival, Alexander Hamilton, accused him of being an atheist, and in the heat of […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username