John—Historian or Theologian?

And even though John, like Mark, begins with an account of Jesus’ meeting with John the Baptist, and John, like all three Synoptics, ends with an extensive narrative of the events culminating in Jesus’ crucifixion, no more than a fourth of the Johannine narrative is found in the Synoptics. The obverse is also the case; no more than a fourth of the content of any of the Synoptics is found in John. If John differs so markedly from the other Gospels, how can this account be historically reliable?

Despite all this, John is the only canonical gospel that explicitly claims to be based on an eyewitness account, that of the Beloved Disciple, an unnamed follower of Jesus who is identified only as the disciple whom Jesus loved: “This is the disciple who is bearing witness to these things, and who has written these things [or “has caused the things to be written”]; and we know that his testimony is true” (John 21:24; see also 19:35). This disciple was in later tradition (before the end of the second century) said to be John, the son of Zebedee, one of the Twelve (see Mark 1:19), but this identification is not made in the Gospel of John itself.

Why is John’s gospel so different from the others?

In antiquity, several explanations were offered. Some proposed that the Gospel of John included events that occurred before John the Baptist’s arrest. (In Mark 1:14, Jesus’ ministry begins only after Herod Antipas arrested the Baptist.) On the other hand, Clement of Alexandria, in about 200, said that John knew that the other Gospels had set forth the physical facts and therefore he wrote a spiritual gospel.

There is an important element of truth in both explanations. At the macro-level, they explain pretty well how John relates to the other Gospels. Yet on the micro-level (individual statements or descriptions of events), there are important differences between John and the Synoptics that these explanations do not quite satisfy. Here are several obvious examples:

In the Synoptics, Jesus’ ministry lasts for less than a year and he goes up to Jerusalem only once, at the end of his ministry, for the week-long Passover festival; he is crucified on that occasion. John mentions three different annual Passover festivals (John 2:13, 6:4, 11:55), indicating not only that Jesus spent more time in Jerusalem but also that his ministry lasted more than two years and perhaps as long as three. Further, in John, Jesus visits Jerusalem not only for Passover, but also for the feast of Tabernacles and Hanukkah.

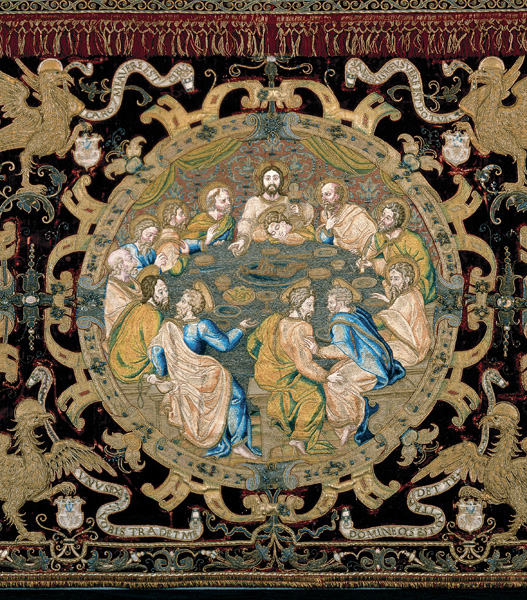

The chronology or calendar of Jesus’ trial and death is also different in John. In all the Gospels, Jesus is crucified on a Friday (Good Friday). But in the Synoptics that Friday is the first full day of the week-long Passover festival, which, in Jewish reckoning, began on the previous evening. Thus, Jesus’ Last Supper with his disciples is the Passover eve meal, and it is explicitly described as such in Matthew, Mark and Luke. In John, however, the Last Supper occurs before Passover (John 13:1), and Jesus is crucified before the advent of the festival. Jesus’ antagonists want to take him down from the cross before the arrival of the festival that evening (John 19:31; compare 18:28). His followers Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus hastily place the body in a nearby tomb so that he is buried properly before the festival begins (John 19:38–42). The apocryphal Gospel of Peter 2:5 seems to follow John’s chronology. Jesus is said to be crucified before the Passover meal. This is also the case in an ancient Jewish source (Baraitha Sanhedrin).1

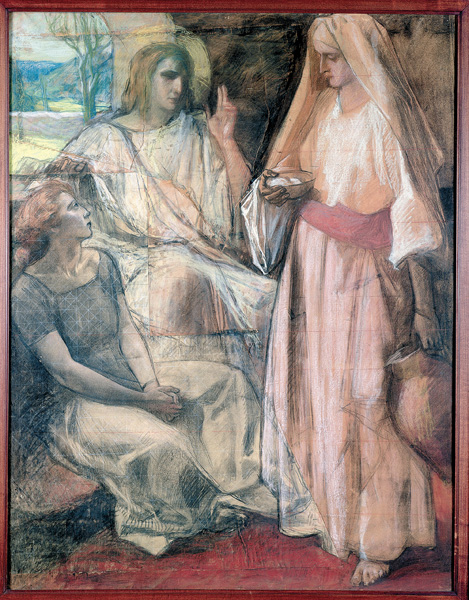

For over a century, the dominant opinion of historical-critical scholarship has been that the Synoptics bring us closer to the historical Jesus than John does. There are good reasons for this. The Jesus of John’s gospel is, as one 19th-century scholar put it, God striding across the earth. Instead of proclaiming God’s kingdom or rule, Jesus proclaims himself as king. He announces that he will do the work of God, including the raising of the dead. There is little doubt that Jesus really was a charismatic healer and demon-exorciser. Probably he saw the power of God’s kingdom or rule already at work in his ministry. In John, however, Jesus’ miracles, or signs, are intended to lead those who see them (or read about them) to faith in Jesus as the Son of God. They are even more awe-inspiring than the miracles narrated in the Synoptics. In John, “Son of God” refers to something more than the Davidic king, who is also called God’s Son (see Psalms 2:7, 89:26–27; 2 Samuel 7:14). As “Son of God,” Jesus is the revelation of God, the extension of God into the world, who can himself be called God (theos; see John 1:1, 18, 20:29).

John presents the incarnation (“becoming flesh”) of God in a paradoxical formulation, foreshadowing later Christian creeds of the fourth and fifth centuries. God striding across the earth is also the son of the human Joseph (John 6:42). “The (other) Jews” know Jesus’ father and mother, and at least some of the people know he comes from Nazareth (John 1:46, 7:41–43), an obscure village. How then, they wonder, can he claim to have come down from heaven? John’s view of Christ’s being and role is quite sophisticated. The God who strides across the earth is also a man whose human origins are well known, who gets tired, sits by a well and asks a Samaritan woman for a drink (John 4:7). He even washes the feet of his disciples (John 13:1–7).

The picture of Jesus in John, particularly his words, his discourses and conversations, are colored, if not created, by later Christian faith in him and, I think, by the inspiration of the Spirit, which Jesus promises to his disciples as his continuing presence after his death and departure: “But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the father will send in my name, he will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all the things I have said to you” (John 14:26; compare 16:12 [Revised Standard Version]).

John also gives us a more extensive account of Jesus’ relation to John the Baptist than the other Gospels. This suggests a much deeper relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus than is reflected in the Synoptics.

In a recent study of Jesus entitled Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews (the title on the cross according to John’s gospel), New Testament scholar Paula Fredriksen has made a simple, but important, observation. Since the other Synoptic Gospels follow the itinerary and chronology of Jesus found in Mark, which is generally agreed to be the earliest gospel, then John is not a minority of one against the other three. It is actually a case of John against only Mark alone.

Mark’s outline of Jesus’ ministry was once thought to be historically accurate. Modern gospel research has shown, however, that Mark’s basic framework has been determined by the author’s theological purpose rather than by historical (that is, chronological and geographical) information. Although in important ways Mark’s portrayal of Jesus (together with Matthew’s and Luke’s) may well be closer to the historical Jesus then John’s portrayal, this does not mean that Mark’s narrative framework is more accurate historically. Maybe John’s is more realistic—and accurate.

That is exactly what Fredriksen contends. While the Johannine account of Jesus’ ministry may not be historically motivated, in important respects it may be the more accurate historically. Is it more reasonable to suppose that Jesus’ public ministry lasted less than one year, or that it lasted between two and three as John has it? The latter period offers more time for Jesus to gather disciples and for opposition to develop, as well as for his fame to spread. That he seems a figure rather well known to the governor Pontius Pilate and to the chief priest Caiaphas is not just a figment of the evangelists’ imagination. Pilate and Caiaphas also knew something about him, because his final visit was not his only visit to Jerusalem during his ministry. In two to three years, Jesus would have gone to Jerusalem for three Passovers, as well as to other festivals, as John portrays him doing. Indeed Mark and Luke both hint that Jesus may have been there before, just as John tells it. According to Mark 11:1–6 (see also Mark 14:12–16), Jesus seems to have prior connections with people in Jerusalem; as he approaches the city, he tells his disciples where they’ll find a colt for him to ride into the city. Mark 14:49 suggests a longer stay there: “Day after day I [Jesus] was with you in the Temple.” Luke 13:34 (“O Jerusalem, Jerusalem … How often have I desired to gather your children together”) suggests Jerusalem was much in Jesus’ thoughts over a long period of time.

In John, Jesus spends enough time in Jerusalem to attract local disciples. (The twelve disciples, mentioned but not named in John, were all Galileans [Mark 14:70; see also Matthew 26:73, where Peter’s Galilean accent is said to betray his Galilean background].) According to John, an unnamed disciple, known to the high priest, has to help Peter gain entrance to the high priest’s courtyard (John 18:15–18). Jesus’ closest disciple (John 13:23), the Beloved Disciple, appears only in Jerusalem, and was presumably a Jerusalem disciple. Perhaps he is the same as the disciple known to the high priest, although that is not said in the text. Given John’s version of Jesus’ several visits to Jerusalem, it would be natural for him to have made disciples in Judea and Jerusalem. Indeed, Mary, Martha and Lazarus of Bethany, just outside Jerusalem, are Jesus’ friends (John 11:1–11, 12:1–2). That Jesus was active for two or three years and spent time in Jerusalem (or Judea) as well as Galilee is thus supported by circumstantial evidence.

To date Jesus’ arrest, trial and execution just before Passover begins, as John does, and not at the beginning of the festival, as the Synoptics would have it, presents far fewer problems for our understanding. Fredriksen points, for example, to the difficulty—indeed, the near impossibility—of assembling the Sanhedrin, the Jewish high court, on the evening of the Passover meal.

New Testament scholar John P. Meier is now producing a definitive study of the historical figure of Jesus (A Marginal Jew; three volumes appeared from 1991 through 2001 with a fourth and final one underway). Like Fredriksen, Meier takes the Gospel of John seriously as a historical source for Jesus’ ministry. Meier not only sees the difficulties of the Marcan account of the trial of Jesus on Passover eve, but believes the Johannine chronology is the correct one. For John, Jesus was arrested the evening before Passover eve, and died before the week-long festival actually began, that is, before the Passover was eaten.

Meier also points out, as does Fredriksen, that the Marcan account of Jesus’ trial before the Sanhedrin is full of illegalities according to Jewish law as set forth in the Mishnaic tractate Sanhedrin (which although not written down until nearly two centuries later, probably embodies earlier legal traditions). These illegalities include (1) holding a capital trial on such a high and holy day; (2) having no witnesses or arguments in favor of the defendant in a capital case; (3) convicting someone of a capital offense when there is disagreement among witnesses who testified against the defendant; (4) immediately executing a capital judgment without allowing at least a day to intervene. Even if the proceedings occurred on the previous evening, before Passover eve (John’s chronology), they would have been highly irregular. John, however, reports no such Sanhedrin assembly and trial even before Passover. Hence, all these problems are avoided in John. Instead, after being arrested and bound Jesus is taken to the house of Annas, the father-in-law of the high priest, Caiaphas, for a brief hearing, after which he is sent by way of Caiaphas (John 18:24) to Pilate. Nothing is said about what went on before Caiaphas. The reader may supply the Marcan trial for the sake of harmonization, but John says nothing about it. That in itself is remarkable, since the verdict of that trial—that Jesus should die for blasphemy because he claimed his messiahship and divine sonship—fits closely the Johannine Jews’ condemnation of Jesus for blasphemy (John 10:33). If there had been such a trial as Mark describes, surely John would have mentioned it.

So John’s account differs from Mark (and the other two Synoptics), but not in the way one would expect. Instead of adopting Mark’s narrative to show that the highest Jewish authority formally condemned Jesus for blasphemy, John omits that impressive trial scene, so elaborately composed by Mark. According to ancient church tradition, John wrote his spiritual gospel in light of the others. But modern critical scholarship has questioned whether John even knew Mark or the other Synoptics. Quite clearly, John did not base his narrative on Mark, as Matthew and Luke did. Had he known Mark, John would not have missed this opportunity to drive home a point against “the Jews” (the Jewish authorities)a that he was elsewhere eager to make. Perhaps he did not know Mark or, even if he did, perhaps he relied on a narrative tradition that was more accurate historically.

Let us turn now to the earlier days of Jesus’ ministry, which in all the Gospels (see also Acts 10:37, 13:24–25) begin with an encounter with John the Baptist. As noted earlier, John’s gospel devotes far more space to John the Baptist than any of the Synoptics. (Incidentally, in John’s gospel, John the Baptist is always called only “John.”) And John gives us a far richer picture of the relationship between Jesus and the Baptist. In his formidable account of the historical Jesus, John Meier refers to the Baptist as Jesus’ mentor—an apt description, and one derived largely from John’s gospel (as Meier acknowledges).

While in all four canonical Gospels, the Baptist’s role is somewhat the same, the Synoptics focus on his preaching of judgment and repentance (see especially Matthew 3:7–12 and Luke 3:7–14). Of central importance in John, however, is the Baptist’s role as a witness to Jesus. John always gets it right about Jesus.

John’s gospel also takes pains to make it clear that the Baptist is subordinate to Jesus: “He who comes after me ranks before me” (John 1:15, 30; see also 1:19–23, 3:30). Jesus is John’s superior. The author wants to make sure that his emphasis on the Baptist doesn’t elevate the Baptist to the level of Jesus. But John’s gospel also portrays Jesus as someone who performs baptisms, in effect putting him on the same level with John (John 3:22, 26, 4:1). As a kind of afterthought, the gospel notes that it is not Jesus, but his disciples, who baptized (John 4:2). Yet there is no mention of their baptizing in the other Gospels. Perhaps the Fourth Gospel reflects the fact that Jesus did for a while baptize, and that the Baptist was his mentor.

Moreover, in the Synoptics, Jesus’ ministry begins only after Herod Antipas arrests John the Baptist. In John’s gospel, Jesus and John the Baptist work at the same time; the Baptist has not yet been put into prison (John 3:24). An ancient explanation of this is that John’s gospel narrates the part of Jesus’ ministry that occurred before the arrest of the Baptist, when they were working side-by-side (perhaps even as rivals), while the Synoptics describe Jesus’ ministry after the Baptist’s arrest. This may well be correct. As Meier has suggested, however, the sharp separation of the ministries of Jesus and John in the Synoptics is much more likely a theological construct—that is, not historical—and the statements about Jesus’ and John’s contemporaneous baptizing activity in John’s gospel are likely to be historical. It is in John’s gospel—and only there—that the Baptist is portrayed as sending his disciples to Jesus. “Look, here is the Lamb of God,” he tells two of his disciples (John 1:36). In all probability, this means that Jesus drew some of his disciples from Baptist circles. Perhaps the evangelist himself was once a disciple of the Baptist. Did John the evangelist and Jesus have a common background, namely John the Baptist?b

Another indication that John’s gospel may be more historically reliable than has often been recognized lies in the evangelist’s knowledge of geography and place names. Some of this data is found in no other gospel. John knows that Jesus is from Nazareth, a humble village in Galilee, and apparently not from Bethlehem (John 7:42). In Jerusalem, John knows the Sheep Gate Pool (John 5:2) and the Pool of Siloam (John 9:7). He has some knowledge of the plan of the Temple and specifically mentions the treasury (John 8:20) and Solomon’s Porch (John 10:23). He knows the Temple has been under reconstruction for 46 years (John 2:20). John’s gospel contains information about Samaria not found in other Gospels: It mentions the city of Sychar, probably the Old Testament Shechem (John 4:5); Jacob’s Well (John 4:6) and a mountain that is obviously Mt. Gerizim, on which the Samaritans offered sacrificial worship (John 4:20). There is no way to guarantee that John’s description of what happened at these places is all historically accurate. At worst, however, it is knowledgeable misinformation! That is, without knowledge of the topography of the country, one could scarcely create such an aura of verisimilitude.

I believe there is much historical information in the Gospel of John, especially where it diverges from the other Gospels. But how can one think of the Gospel of John as historical and John as an historian in any meaningful sense when the central figure in the narrative—Jesus—appears as a stranger from heaven (as one interpreter aptly described him), speaking always of himself and his role and his descent from heaven? As has long been noted by most commentators, such discourses are so different from what we find in the several traditions that make up the other Gospels—not to mention ordinary human speech—that they can scarcely be credited as the words of Jesus of Nazareth.

Apparently, early Christianity put on the lips of this Jesus its beliefs and confessions of faith in him. Not coincidentally, the language of the Gospel of John is taken up centuries later into the church’s creeds.

How then can we reconcile these two aspects of John’s gospel—the historical and the theological? John has a distinctively theological view of history in which God is the prime mover. The historical and the theological are not unrelated, but they do not fully coincide. That is, John’s differences from the other Gospels do not always support his theology, which suggests they may be historically accurate. Thus, at the beginning, John mentions Jesus’ baptizing alongside John the Baptist, who appears to have been Jesus’ senior and mentor, despite protestations to the contrary (John 1:15, 31). Further, at the end, John omits mention of the condemnation of Jesus for blasphemy by the high court of Judaism, although that fits John’s own view of Jesus’ demise (and is mentioned, by contrast, in Mark). Other examples are less clear-cut. John describes a ministry of Jesus that lasts two to three years (three Passovers), and that includes several visits to Jerusalem more frequently for annual festivals; John’s Jesus is thus able to confront “the Jews” centered in Judea and Jerusalem. This fits John’s agenda. Yet it is not unlikely on other grounds that Jesus’ ministry lasted longer than the period of a year or less that the Synoptic narrative requires. If so, as an able-bodied Jewish male he would have naturally gone up to Jerusalem for more than one Passover or other festival. Another ambiguous example: It is sometimes maintained that John moved the (Jewish) calendar date of Jesus’ crucifixion to the day of the Passover eve meal, so that Jesus would have died as a sacrificial Passover lamb. (Remember, John the Baptist had said of him: “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world “ [John 1:29].) Yet John’s dating presents fewer historical difficulties than the Synoptics, for the Synoptics have Jesus tried on Passover eve and executed on the first full day of the festival.

John’s narrative is surely deeply theological. Yet this does not necessarily mean that John creates narratives out of theology, without regard for history. John’s gospel presents an unusual weaving together of historical data and theological interests.

For John, the transcendent God profoundly impinges on this world. In John’s concept of revelation, Jesus reveals God, makes God known. That is Jesus’ principal function (John 1:18). To do so, he descends from heaven (John 3:13), but this does not mean he was not born (John 18:37). He has a mother (John 2:1), brothers (John 2:12, 7:3), and a father, Joseph (John 1:45). His opponents are bewildered at his claim to have come down from heaven as the bread of life, because they know his father Joseph and his mother (John 6:42). What could Jesus possibly mean by such a claim? When a voice from heaven (God) addresses Jesus (John 12:28), some think it has thundered, others that an angel has spoken to him (John 12:29). Jesus then says, “This voice has come for your sake, not for mine” (John 12:30). Probably for the readers’ sake.

Like many biblical writers, John understands history as the arena in which God’s purpose is fulfilled. It is the stage on which God, through Jesus, reveals himself. That revelation can only be received by eyes of faith. Some see and do not perceive or receive the revelation. Again a Johannine paradox: the initiative lies wholly with Jesus, who says, “You did not choose me, but I chose you” (John 15:16). Yet the movement from the divine side must be accompanied by a movement from the human: “My teaching is not mine, but his who sent me; if any man’s will is to do his will, he shall know whether the teaching is from God or whether I am speaking on my own authority” (John 7:16–17). God is the first cause in history, but God’s causation does not exclude human causation. They are held in paradoxical tension. John then is a theologically centered historian.

Is John changing history (or creating it) to serve his theology? Or is he weaving his theological insights into an historically based narrative?

I realize that one can go either way, but to assume the former—as has so frequently happened in Johannine exegesis—often involves the historical judgment that, where John and the Synoptics differ, historically the Synoptics are obviously to be preferred. It’s not so obvious after all. We have enough cases where John’s differing version is historically more plausible than the Synoptics to justify our giving the Fourth Gospel at least equal consideration.

Footnotes

The Greek term Ioudaioi (“Jews”) is frequently translated as “the Jewish authorities” in modern translations. This is historically accurate. In the trial narrative, the term Ioudaioi seems synonymous with the “chief priests,” as it had earlier been with the “Pharisees.” In either case they are the Jewish authorities. Surprisingly, in John the Pharisees do not appear in the Passion narrative (the account of Jesus’ arrest, trial, and death). And indeed this is true in the Synoptics as well. Very probably this reflects the fact that the Jewish religious party that debated most vigorously with Jesus during his public ministry did not play a crucial role in putting him to death. Evidently, that role fell to the chief priests, who in Acts are portrayed as pursuing and persecuting the followers of Jesus in Jerusalem after his death and departure.

Rudolf Bultmann made these suggestions in his justly famous commentary on John, published in German in 1941 and in English translation 30 years later. Unfortunately, he did not pursue them. Had he done so he might have come to more positive conclusions about the historical value of the Gospel of John.