052

As we go to press, the National Geographic has announced the publication of a substantially revised edition of its The Gospel of Judas, which it originally published less than two years ago, in 2006. The new edition is not yet available for sale but has been made available to the media. It is clearly a reaction to the scholarly criticism detailed in the following article.

According to the National Geographic’s advance promotional material, the new edition includes “new readings and new interpretations” and “a thoroughly updated translation” of the Gospel of Judas. In other words, the new edition recognizes the flawed scholarship of the original edition. As one of the contributors to the revised edition (Gesine Schenke Robinson), who was not on the original team, observes, “The Gospel of Judas had captivated the imagination of the first editors to a much greater extent than the text itself supports … Mistakes have been acknowledged,” including “the sensationalized reading.”

Whether purchasers of the original edition, which made The New York Times’s bestseller list, can trade in their copy for the revised edition is not mentioned.

“When the hype calms down, the serious scholarship can begin,” observes the revised edition. What follows is serious scholarship by one of the world’s leading Gnostic scholars.—Ed.

I regret to say that the National Geographic Society has opened itself to serious criticism regarding its publication of the now-famous Gospel of Judas.

In the first instance, it pitched its enormous publicity machine to imply that the newly released Gospel of Judas contains what may be a historically reliable alternative portrait of Judas Iscariot, not as he is portrayed in the New Testament as Jesus’ betrayer, but as a hero, the 13th disciple who is closer to Jesus than the other 12. When, according to the National Geographic version, Jesus asks Judas to betray him, Jesus is thereby allowing his spiritual self to be freed from his mortal body at the time of his death. And Judas is therefore rewarded with an ascent to the divine realm above.

BAR has already criticized the National Geographic for “selling” the Gospel of Judas as possibly recounting actual history.a In fact, no scholar would treat it this way, including the National Geographic scholars themselves. As the BAR notice stated, “The idea that this new gospel might be an accurate historical report of the reason for Judas’s betrayal of Jesus is arrant nonsense.”b

The BAR notice went on to note that, although the Gospel of Judas has nothing to tell us about the historical Judas Iscariot, it has much to tell us about Gnostic 053Christianity. That is true. But, unfortunately, the scholars whom the National Geographic engaged to reconstruct and translate the Gospel of Judas basically misunderstood what it really says.

This second lapse may not be the National Geographic’s fault. They employed prominent and competent scholars for the task.1 Perhaps it happened because the National Geographic treated the project more like an Oscar secret than a scholarly endeavor. The scholars were required to sign a confidentiality agreement to assure the National Geographic of an exclusive. The result was that the scholars working on the text could not profit from the usual scholarly interchange. James Robinson, the hero of the Nag Hammadi codices (the largest cache of Gnostic documents ever found in modern times), was deliberately excluded from the National Geographic group of scholars. There may be a certain irony in this. The National Geographic has rightfully been criticized for handling the matter like a public relations circus; as a result, it got a fundamentally flawed product from the scholars to whom it was restricted. As the Rice University Coptic scholar April DeConick wrote in The New York Times (December1, 2007):

The situation reminds me of the deadlock that held scholarship back on the Dead Sea Scrolls decades ago. When manuscripts are hoarded by a few, it results in errors and monopoly interpretations that are very hard to overturn even after they are proved wrong.

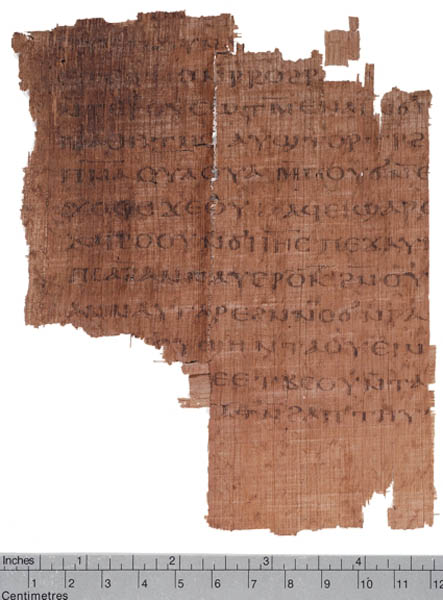

The Gospel of Judas of course lent itself to this publicity extravaganza because of its genuine cloak-and-dagger history. The codex (a codex is a book of sheets bound as a book) containing the Gospel of Judas includes three other documents. It was looted from an ancient tomb in Egypt in the 1970s, together with another Coptic codex and two Greek ones, and eventually found its way to the antiquities market. Only much later was the text of the Gospel of Judas recognized for what it is. In 1983 the Egyptian antiquities dealer who had the codex with its still-unidentified Gospel of Judas offered it and the other codices for sale in Geneva for three million dollars.2 Not surprisingly, there were no takers.

The Egyptian who still controlled the codex then flew it to the United States, where it languished in a bank vault on Long Island for 16 years, during which time it suffered severe damage.

When Zurich antiquities dealer Frieda Tchacos Nussberger finally got control of the codex in 2000, she showed it to experts at Yale University, where, for the first time, it was recognized as containing the Gospel of Judas. Yale professor Bentley Layton noticed the title at the end of the third tractate: “The Gospel of Judas.” Yale declined to purchase the codex, however, fearing legal problems. Nussberger had the codex flown back to Switzerland, where she managed to arrange with the Maecenas Foundation of Ancient Art in Basel to have the 054text conserved. Eventually the National Geographic Society was brought in to finance the project, for which it was given exclusive publication rights. The codex has been named the Codex Tchacos in recognition of the part played by Frieda Tchacos Nussberger.

The critical edition of the Codex Tchacos has recently appeared. It includes the Coptic transcriptions, translations, introductions, indices and photographic plates of the manuscript.3 Unfortunately, the plates are reduced to 56 percent of actual size, which makes it very difficult for other scholars to use. (Since the recent widespread criticism of the National Geographic transcription and translation, however, full-size photographs have been made available online.)

Scholarly criticism of the National Geographic interpretation of the Gospel of Judas has been widespread. My own assessment of their work was presented in a paper at the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in San Diego in November 2007. After I had prepared that paper, I received a copy of April DeConick’s new book.4 I am happy to say that she and I have independently come to very similar conclusions regarding what the Gospel of Judas really says about Judas. There are others as well. In a very recent book, one of the National Geographic scholars, Marvin Meyer, refers to three scholars who have proposed “a revisionist understanding” of the Gospel of Judas. In addition to DeConick, Meyer names Louis Painchaud of the University of Laval, Quebec, and John Turner of the University of Nebraska—Lincoln, all outstanding Gnostic scholars. This is not to denigrate the distinguished reputation of the National Geographic scholars, only to emphasize the growing scholarly dissatisfaction with their work. I am happy to count myself as one of the group that Meyer calls “revisionists.”

What are the “revisions”?

Earlier in this article, I gave my view that the National Geographic scholars basically misunderstood what the Gospel of Judas is really saying. This has two aspects: first, a failure to appreciate fully the Gnostic context of the Gospel of Judas; and, second, a mistranslation of some critical passages in the text.

Let’s begin therefore by talking a bit about the Christian Gnosticism that provides the context for the Gospel of Judas. (Incidentally, the Gospel of Judas was originally written in Greek; what we have here is a Coptic translation; Coptic is the latest form of ancient Egyptian.)

The Pastoral Epistle designated 1 Timothy, although it is attributed to Paul in the New Testament, is now recognized as post-Pauline. It was written sometime in the early second century by a Paulinist Christian writing a letter in the name of Paul. It includes the following warning: “Avoid the godless chatter and contradictions of what is falsely called knowledge, for by professing it some have missed the mark as regards the faith.” (1 Timothy 6:20–21). In the italicized words we may see a testimony to the beginnings of Gnosticism.

In about 180 A.D., Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons, wrote a five-volume work against various Christian “heresies.” In this massive work Irenaeus uses the same word as 1 Timothy—“so-called knowledge”—to characterize most of these heresies. Since the 17th century, scholars have used the term “Gnosticism” to characterize these “heresies,” a term based on the Greek adjective gnostikos (“knowledgeable”), derived from the Greek word for knowledge, gnosis.

Many adherents of ancient Gnosticism referred to themselves as “gnostikoi,” to distinguish themselves from people who lacked gnosis. The term “Gnosticism” covers a wide variety of religious beliefs and practices, but an essential feature of Gnostic religion is the emphasis on knowledge, rather than faith or observance, as the basis for salvation.

The content of this knowledge is essential to salvation and involves an innovative theology, cosmology, anthropology and soteriology (the study of salvation).

In Gnostic theology the Biblical God is split in two: (1) a transcendent, essentially unknown God and (2) a lower creator god responsible for the material world.

In Gnostic cosmology the world is seen as a prison in which human souls are held captive by a malevolent creator and his minions.

In Gnostic anthropology the essential human spirit is regarded as co-substantial with the highest God but imprisoned in this world in a material body.

And in Gnostic soteriology, gnosis, revealed from above, awakens the imprisoned spirit and enables it to escape the confines of the body and the material world and return to its divine origins.

These teachings are given expression in elaborate Gnostic myths, attributed to various revealers. In Christian Gnosticism, Jesus Christ is the Gnostic revealer.

Until recently, scholars studying the various Gnostic movements had to rely on Irenaeus and other church fathers for testimonies about the Gnostics and their writings. But then, some two years before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, a cache of ancient documents was discovered in Upper Egypt: the 05513 Nag Hammadi codices, named for a town not far from the place of their discovery. These manuscripts contain primary Gnostic texts that provide massive new evidence for ancient Gnostic religion, both Christian texts and non-Christian texts.

Of somewhat less significance, but nevertheless important, is the Berlin Gnostic Codex, discovered in the late 19th century but only published in 1955, with a German translation. The one-volume edition of Gnostic texts, The Nag Hammadi Library in English, published in 1977 (edited by James Robinson), contains two tractates from the Berlin Codex.

And now we have the Gospel of Judas.

As already noted, until the discovery of these documents, scholars were dependent almost exclusively on Irenaeus and a few subsequent Christian writers for their understanding of Gnosticism. In a passage that is not always easy to understand, Irenaeus portrays one group of these heretical Gnostics who are said to use a “Gospel of Judas”:

Others again say that Cain was from the superior power, and confess Esau and (the tribe of) Korah and the Sodomites and all such as their kinsmen. They were attacked by the creator, but none of them suffered any ill. For Sophia snatched away from them to herself what belonged to her. This Judas the traitor knew very well, and he alone of all the apostles recognized the truth and accomplished the mystery of the betrayal, by which everything earthly and heavenly is dissolved, as they say. And they produce a fabrication, which they call the Gospel of Judas.5

Although this language is sometimes opaque and ambiguous, it is nevertheless clear that Irenaeus is telling us that certain Gnostics transform Judas and other Biblical villains into heroes. For Irenaeus, this Gnostic portrait of Judas is a “fabrication.”

Irenaeus regards the Gospel of Judas as a heretical text. What would a heresy do but transform the most evil, dastardly betrayer into a hero! Judas is singled out 056and distinguished from the other disciples because only he “recognized the truth,” according to this heretical view. All this can be found, Irenaeus tells us, in a gospel used by the Gnostics called the “Gospel of Judas.”

Let us now look at the Gospel of Judas itself, rather than Irenaeus’s view of it. It is quite different.

At the beginning of the gospel, only Judas knows who Jesus is and where he has come from, that is, from the divine realm above this world (in the mystic language of the gospel, from “the immortal aeon of Barbelo” [35:17–18]).6 The other disciples are ignorant of the highest God and blindly worship the creator god Saklas. The other disciples also think that Jesus is the son of their god Saklas. Jesus simply laughs at their ignorance. Jesus separates Judas from the other disciples and gives him a special revelation about “the mysteries of the kingdom.” It begins to look as if Judas might be a hero. But a careful reading of the text will show that “the kingdom” whose mysteries are revealed to Judas is associated only with the “error of the stars” (46:1–2), that is, with the lower world governed by fate. Jesus tells Judas that he will grieve much when he sees that kingdom, and then Jesus laughs.

There is worse to come. While it is true that only Judas knows Jesus (as indicated above), Judas has this knowledge only because he, Judas, is a demon—daimon in the Coptic text. Later in the gospel, Jesus addresses Judas as the “thirteenth demon (daimon).” No hero here.

Strangely, Marvin Meyer, the National Geographic translator, renders daimon in English as “spirit.” Karen King in her translation misfires even worse; she translates it “god.”7 As April DeConick has pointed out, daimon can only mean “demon” in Gnostic contexts.8

At first it may seem surprising that a demon would be the only one to recognize Jesus as the son of God. But in the New Testament, too, demons recognize Jesus as the “son of God” (see Matthew 8:29; Mark 1:34; Luke 4:41). So, properly understood, Judas is no hero simply because he recognizes Jesus as the son of God.

Why does the Gospel of Judas call Judas “the thirteenth” disciple? This is a reference to the 13th aeon in the lower world occupied by the world-creator Saklas, the lower god whom the other disciples worship in Gnostic mythology. And that is where Judas will wind up (55:10–11).

That Judas will not ascend to the holy generation above is made absolutely clear: “You will not ascend to the holy [generation]” (46:25–47:1). Unfortunately, the National Geographic translation also mistranslates this passage, simply omitting the crucial “not.” The National Geographic translation reads: “They will curse your ascent to the holy generation.” This gives the sentence precisely the opposite meaning from what the text is saying.

Toward the end of the Gospel of Judas, it refers to the evil sacrifices offered by the Twelve to their god Saklas. Judas will also be sacrificing to Saklas. But Judas is even worse than the Twelve; Jesus prophesies what Judas is going to do: “You will do worse than all of them. For the man that clothes me, you will sacrifice him.” It is a supreme irony that Judas’s sacrifice will enable Jesus’ spirit to be freed from the body and ascend on high.

Again, the National Geographic translation misfires: Instead of Jesus saying to Judas, “You will do worse than 057all of them [the Twelve],” the National Geographic translation states, “You will exceed all of them.” Building on this translation, the statement that “you will sacrifice the man that clothes me” is taken to mean that Jesus is asking Judas to sacrifice him so that his spirit can be freed from his immortal body. But it means no such thing.

A number of other mistranslations could be cited, but this is enough to indicate why the National Geographic translation is flawed not only by mistranslations but also by misunderstandings of the text.

In the final narrative of the Gospel of Judas, Judas is lurking outside the room where Jesus is at prayer, presumably with the other disciples at the Last Supper. Judas is approached by some “scribes” who ask him, “Aren’t you the disciple of Jesus?” The gospel concludes with this terse comment, “He answered them as they wished. Then Judas received some money. He handed him over to them” (58:23–27). He is as guilty here as he is in the New Testament. He is surely no hero.

The Gospel of Judas is a vicious Gnostic broadside against the “catholic” and “apostolic” church represented by a growing ecclesiastical establishment during the second century. Irenaeus was the most important representative of that establishment and is probably the most important figure in the ancient church in the development of Christian “orthodoxy.”

The anti-catholic polemic of the Gospel of Judas can be seen in how the 12 disciples are portrayed. At the beginning Jesus appears to the disciples as they are offering thanks over the bread to their god Saklas. Jesus laughs at them and tells them that they are under the spell of their god. They are wrong to think that Jesus is the son of their god Saklas (32:22–35:1). It is at that point that Judas expresses his recognition of who Jesus really is.

The next day Jesus again appears to the 12 disciples. They ask him where he has been. He replies that he has been to “another great holy generation” (36:16–17). When they ask him about that generation, Jesus laughs. He makes it clear to them that they are from the mortal human generation, and have no part in the holy and immortal generation (36:18–37:20).

On another day Jesus appears to them, and they tell him that they have seen him in a vision: They saw a great temple with an altar, with priests offering their children and wives as sacrifices, and committing other unspeakable atrocities, all in Jesus’ name. Jesus’ interpretation of the disciples’ vision is startling: “You are those you saw who presented the offerings upon the altar” (39:18–20). The disciples are committing these lawless deeds as acts of worship of their god Saklas, the creator of the lower cosmos.

The 12 disciples in the Gospel of Judas are symbols of the proto-orthodox church of the second century, a church that claims to have been founded by these disciples. Members of this church worship the creator god, rather than the true God above. The worship service of the 12 disciples centers on the Eucharist, a sacred meal of bread and wine that recalls the sacrificial offering of Jesus’ body and blood on the cross. According to the Gospel of Judas, the god that proto-orthodox Christians worship is a vicious being who causes his own son to undergo a horrible death. In short, the proto-orthodox Christian contemporaries of the author of the Gospel of Judas are ignorant of the true God, and they will wind up in perdition.

What would lead the author of the Gospel of Judas to draw such conclusions regarding some of his Christian contemporaries? The answer is that the author was a Gnostic.

As we go to press, the National Geographic has announced the publication of a substantially revised edition of its The Gospel of Judas, which it originally published less than two years ago, in 2006. The new edition is not yet available for sale but has been made available to the media. It is clearly a reaction to the scholarly criticism detailed in the following article. According to the National Geographic’s advance promotional material, the new edition includes “new readings and new interpretations” and “a thoroughly updated translation” of the Gospel of Judas. In other words, the new edition recognizes […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Endnotes

The three scholars who reconstructed and translated the text are Rodolph Kasser, Marvin Meyer and Gregor Wurst, who collaborated on The Gospel of Judas from Codex Tchacos (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2006). Meyer prepared the English translation. The book also includes an essay by Bart Ehrman titled “Christianity Turned on Its Head: The Alternative Vision of the Gospel of Judas.” The interpretation of the figure of Judas found in that book has been followed by other scholars in hastily written books, including Elaine Pagels and Karen King, Reading Judas: The Gospel of Judas and the Shaping of Christianity (New York: Viking, 2007).

The story of the find and the disastrous mishandling of the Codex has been told by Herbert Krosney in The Lost Gospel: The Quest for the Gospel of Judas Iscariot (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2006).

The Gospel of Judas, Together with the Letter to Philip, James, and a Book of Allogenes from Codex Tchacos, Coptic text edited by Rodolph Kasser and Gregor Wurst, introductions, translation and notes by Rodolph Kasser, Marvin Meyer, Gregor Wurst and François Gaudard (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2007).

April DeConick, The Thirteenth Apostle: What the Gospel of Judas Really Says (London/New York: Continuum, 2007).

Against Heresies 1.31.1, in Werner Foerster, Gnosis: A Selection of Gnostic Texts. English Translation Edited by R. McLachlan Wilson , vol. 1 Patristic Evidence (Oxford: Clarendon, 1972), pp. 41–42.

Quotations from the Gospel of Judas are taken from the new translation found in DeConick’s book The Thirteenth Apostle.