For 2,000 years Jews and Christians have mentioned Queen Esther and the widow Judith in the same breath. And it’s not surprising. Both women are Jewish heroines in popular books named after them. Both women were beautiful, resourceful and brave. And the books bearing their names are among the most interesting and best-written in the Bible.

Ultimately, however, these two books experienced drastically different fates. Esther was canonized and is sacred scripture for both Jews and Christians. Judith, on the other hand, is noncanonical, apocryphal, for Jews and Protestants; and deutero- (that is, second-) canonical for Roman Catholics.1

That Jews accepted the book of Esther but rejected the book of Judith is especially puzzling2 because Judith is obviously a religious book, while Esther, on the surface at least, is not.3 God is not even mentioned in the book of Esther, a notable distinction shared only with the Song of Songs in the entire Hebrew Bible.4 Nor do we find in the book of Esther such distinctive Jewish themes and institutions as covenant, the Law, prayer, the Temple, sacrifice and kashrut (dietary laws). By contrast, these and many other religious beliefs and practices characteristic of Judaism are inextricably woven into Judith—and in quite orthodox fashion. Why, then, was the “orthodox” book of Judith rejected from the Jewish canon?

One theory is that it contains too many “errors”; other; more subtle “flaws” may also have played a part.

A mere 16 chapters, Judith can be divided into two parts: “The Prelude” (chapters 1–7) and “The Action” (chapters 8–16). The Prelude begins when King Nebuchadnezzar, king of the Assyrians, leaves his capital Nineveh in the 12th year of his reign to war against the great Median king Arphaxad. Various peoples in Mesopotamia fight at Nebuchadnezzar’s side. In the west, however, the countries he invites to march with him against Arphaxad not only refuse but treat his envoys with contempt. Nebuchadnezzar swears that some day he will avenge himself on them.

Despite these refusals of aid, Nebuchadnezzar, five years later, defeats Arphaxad and destroys his “invulnerable” city of Ecbatana (chapter 1). Now Nebuchadnezzar is ready to carry out his earlier threat against the western countries. Nebuchadnezzar commissions his most able general, Holofernes, to quell the rebellious spirit of the Western nations, with an army of 120,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry, Holofernes is successful. Some nations simply submit and present Holofernes with tokens of submission, such as offerings of earth and water. Those countries that resist, however, are utterly destroyed.

Holofernes proceeds to carry out his cruel commission with a vengeance. His huge army covers the distance between Nineveh and the plain of Bectileth in northern Cilicia in a three-day march, cutting through the lands of Put and Lud, plundering the Rassisites and then, after crossing the Euphrates River, proceeding through Mesopotamia to Cilicia and Damascus.

By late spring, Holofernes has wreaked total havoc on the Midianites and those living in the Damascus Plain, with the result that inhabitants of Mediterranean cities like Sidon, Tyre, Sur, Okina, Jamnia, Azotus (the Hellenistic name for ancient Ashdod), and Ashkelona are so terrified at his approach (chapter 2) that they surrender, unconditionally. Despite their surrendering, Holofernes not only drafts their ablest men into his army but demolishes their sanctuaries and cuts down their sacred poles, insisting that Nebuchadnezzar—and only Nebuchadnezzar—is to be worshiped as god (chapter 3).

Having heard what Holofernes has done to the other nations and that he is now consolidating his enlarged forces in the Esdraelon valley between Geba and Scythopolis (the Greek name for Beth-Shean), the Israelites in Judea are greatly concerned for Jerusalem and their Temple. (They have only recently returned from exile in Babylonia, and their Temple has just been rededicated.)

On the orders of the High Priest Joakim, all the Israelites prepare for war. Towns like Bethulia and Bethomesthaim in the Samaritan hill country secure their narrow mountain passes, through which the Assyrians must pass to gain access to Judea and Jerusalem. Meanwhile, the priests in Jerusalem continue to offer the prescribed sacrifices while all Israelites, dressed in sackcloth and ashes, beg God with prayer and fasting to spare them and the Temple (chapter 4).

On learning that the Israelites plan to resist, Holofernes inquires about them from his staff. From Achior, commander of his Ammonite contingent, Holofernes receives a brief history of the Israelites, including their origins in Chaldeab and their expulsion from there for religious reasons; their emigration, first to Canaan for a while, and then later to Egypt, where they subsequently became slaves. Thanks to the miraculous intervention of their God, Achior relates, the Israelites were expelled from Egypt and even escaped through the Red Sea, which their God had dried up for them.

Achior goes on to say that after a stint wandering in the Sinai, the Israelites settled in Canaan where their fortunes fluctuated, depending upon how faithful they remained to their God. Their increasing wickedness, however, resulted in their country and Temple being destroyed, and they themselves going into exile. In fact, they had recently returned from there and had just rebuilt their Temple in Jerusalem.

Achior concludes his presentation by advising Holofernes to bypass the Israelites; for unless the Israelites sinned against their God (which Achior thought unlikely), their God would not allow anyone to defeat them (chapter 5).

Incensed by Achior’s advice, Holofernes insists that Israel’s God could not save them because only Nebuchadnezzar is god. The Israelites, Holofernes assures Achior, will be destroyed, and Achior with them. For Holofernes will “deliver” Achior into the hands of those Israelites, in whom Achior has so much confidence, to share with them their fate!

Later, when scouts from Bethulia, a small Israelite city south of Esdraelon and near Dothan, find Achior, bound hand and foot, at the bottom of their hill, they bring him into town. There, he is interrogated in the people’s presence by Uzziah, the chief magistrate. After Achior tells the Israelites his story, everyone commends him; and Uzziah even takes him in as his house guest (chapter 6).

Holofernes then deploys his army in the valley near Bethulia, occupies the surrounding hill country, and, on the advice of the commanders of the Edomites and Moabites, seizes the town’s water supply outside its walls.

After 34 days of siege—their water and courage just about gone—the Bethulians bitterly criticize their magistrates for not having originally surrendered the town to Holofernes’ army. The townspeople argue that it is better to live as slaves than to be dead Bethulians!

Magistrate Uzziah proposes a compromise: If God does not somehow come to the town’s rescue within the next five days, the Bethulians will surrender to the Assyrians. Satisfied with this promise, the people return to their respective tasks, although with very low morale (chapter 7). So ends the Prelude. Now for the Action.

Judith, one of Bethulia’s wisest and most religious citizens, was not present at the meeting when this compromise was reached. A wealthy and very beautiful young woman, Judithc is the daughter of Merari and widow of Manasseh. She lives an abstemious life, always fasting and, except on special occasions, wearing sackcloth. Judith so fears God that everyone speaks well of her.

Appalled at the compromise, Judith immediately summons the chief magistrates to her home and chides them for trying to force God’s hand by setting a time limit for him to act. God, she insists, cannot be threatened or cajoled. He can do whatever he wants with his people. Although Israelites deserved their past suffering, since their return from exile the people had remained faithful. Viewing their present predicament as a test rather than as punishment, Judith advises the Bethulians to stand firm and block Holofernes’ route to Jerusalem.

Judith then reveals that she has a secret plan, which requires that she, along with her trusted maid, be permitted to leave town for the next several days. Willing to try anything, the desperate magistrates promptly give their permission (chapter 8).

At the precise moment the evening’s incense is offered in the Temple at Jerusalem, Judith prays to God, reminding him how he had helped her ancestor Simeon avenge himself against the Shechemites for Hamor’s raping of his sister Dinah (Genesis 34:1–31 and 49:5–7). Judith begs God to grant her—a female and a widow—the strength to carry out her plan against the arrogant Assyrians, thereby sparing Jerusalem and letting all the world know that the Lord God, alone, protects Israel (chapter 9).

Her prayers finished, Judith removes her widow’s weeds, bathes, and puts on the expensive clothes and jewelry she had worn when her husband was alive. Now, dressed to kill, Judith gives her maid their kosher provisions and dishes; and, with the blessing of the town fathers, the two women leave under the cover of darkness.

But they are soon discovered by an Assyrian patrol. Struck by her great beauty, the soldiers accompany her with a large honor guard to the camp of Holofernes, where rumors of her loveliness quickly spread (chapter 10).

Holofernes tries to reassure Judith of her safety. Her response is to insist in a polite but firm way that if he will follow her advice, then “God will accomplish something through you, and my lord will not fail to achieve his ends” (11:5). Shamelessly flattering Holofernes, she reiterates Achior’s view that as long as the Israelites have not sinned, no evil can befall them. But, she says to Holofernes, her people are about to commit a sacrilege by drinking the blood of slain cattle and eating prohibited food (a charge that she has apparently invented!). God will reveal to her in her prayers when this happens. Then, she promises Holofernes, she will reveal to the Assyrians the route to Jerusalem. In fact, she says, she will personally lead the way!

Holofernes is utterly captivated by Judith’s beauty, as well as her brains (chapter 11). Still, he is a bit dubious when, on declining to share his lavish but non-kosher food, she answers, saying, “Your servant will not exhaust her supplies before the Lord God accomplishes by my hand what he had planned” (12:4b).

For the next three days Judith follows the same routine, remaining secluded in her tent during the day and, at night, going outside the camp with her maid to bathe, pray and await “the revelation” that the Israelites had sinned.

Frustrated by four days of desiring her, Holofernes, through his majordomo Bagoas, invites Judith to a small party in Holofernes’ tent. Judith eagerly accepts the invitation, telling Bagoas, “Who am I that I should refuse my lord? I will do whatever he desires right away, and it will be something to boast of until my dying day” (12:14).

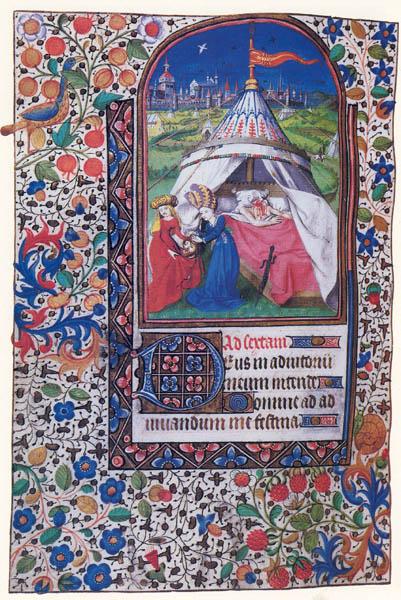

A little while later, after all his guests had left, Holofernes’ lust having been stimulated by much wine as well as by the sight of Judith reclining there on one of his lambskins (chapter 12), he lies down Judith’s feet—dead drunk! Standing beside his bed, Judith prays silently: “Lord God of all power, look in this hour upon the work of my hands for the greater glory of Jerusalem, for now is the opportunity to come to the aid of your inheritance, and to carry out my plan for the destruction of the enemies who have risen up against us” (13:4b–5).

She goes to the bedpost by Holofernes’ head, takes his sword and grabs Holofernes’ hair. Then, praying, “Lord God of Israel, give me strength, now!” (13:7), Judith strikes Holofernes’ neck twice with all her might and chops off his head.

Judith rolls the body of Holofernes off the couch, snatches his magnificent canopy and stuffs it, along with the head, into a sack. Then, as usual, she and her maid leave the camp, ostensibly “to pray.”

Instead, they go back to Bethulia, where Judith displays her trophy, proclaiming to all, “The Lord has struck him down by the hand of a female!” Moreover, she assures them, her honor is still intact: Holofernes has not laid a hand on her (chapter 13)!

For whatever reason, Achior, a battle-seasoned warrior, faints on seeing the head of Holofernes. So impressed is Achior with what God has done for Israel that he converts to Judaism and is circumcised. (His descendants remain Israelites even to the time when the book of Judith was written.) Judith then proceeds to explain her battle plans.

The next day, everything happens exactly as Judith has planned. Seeing the Bethulians coming down to fight with them, the Assyrians alert their leader, only to find him—and themselves—headless! (chapter 14) In their surprise and fear, the Assyrians panic, running in every direction before finally retreating to the northeast beyond Damascus, but only after they sustain heavy losses at the hands of the Israelites.

While visiting the deserted enemy camp, the high priest Joakim speaks for all when he says to Judith, “You are the great boast of our nation! For by your own hand you have accomplished all this. You have done well by Israel; God is well pleased with it” (15:9c–10b).

Looting of the enemy camp continues for a whole month and culminates in a victory parade, starting at Bethulia and ending at Jerusalem (chapter 15).

Judith herself composes a song of thanksgiving, describing how the Assyrians had boasted of the terrible things they would do to Israel and how God has foiled their plans. Judith’s own role is gleefully described by the people, who sing:

“But Judith daughter of Merari Undid him by the beauty of her face. For she took off her widow’s dress To rally the distressed in Israel. She anointed her face with perfume. And put on a linen gown to beguile him. Her sandal ravished his eyes; Her beauty Captivated his mind. And the sword slashed through his neck!”

(Judith 16:6–9).

Judith ends her hymn by insisting that God values reverence far more than sacrifices or burnt-offerings, and that some day he will take revenge on the wicked nations, consigning their flesh to fire and worms forever!

Having dedicated to God all the booty and gifts the people had presented her, Judith returns to Bethulia. There she lives, her fame ever growing, until the ripe old age of 105. Although many men want her, she never remarries. Judith manumits her faithful maid. Before she dies, she distributes her property to her relatives on both sides of the family. Judith is buried in the same cave as her husband, and all Israel mourns her for seven days. As the result of her heroic acts, we are told, no one threatened Israel until a long time after her death (chapter 16).

The story’s basic ingredients are God, power, sex and death. Small wonder people, including many who don’t know too much about the Bible, know that Judith was “the woman who cut off the general’s head.”

When we examine the book more closely, however, its “errors” and “flaws” soon become apparent, and this may explain why it didn’t make the canon.

From the book’s first words, we are jarred by incongruities in time, in geography, and in the identities of key people. Throughout the book, real places and people are mixed with places and individuals known from no other source. For example, the great Median king Arphaxad and Judith’s hometown of Bethulia are known from no other source, suggesting they were created for the story.

From other books in the Bible—and from extra biblical sources—we know that Nebuchadnezzar (605–562 B.C.E.d) was king of the Babylonians, not, as we are incorrectly told in the book of Judith, the Assyrians. And his capital was Babylon, not Nineveh. Nebuchadnezzar didn’t destroy Nineveh, the book of Judith to the contrary notwithstanding. Nabopolassar, Nebuchadnezzar’s father, was the one who destroyed Nineveh (in 612 B.C.E.) and then made it his capital. As for Ecbatana, whose destruction is also attributed to Nebuchadnezzar in the book of Judith, it was not until after Nebuchadnezzar (in 544 B.C.E.) that it was first conquered (but not destroyed) by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenian empire.

Judith’s Nebuchadnezzar claims to be a god, but no historical Assyrian, Babylonian, or Persian king ever actually made such a claim.e

The most egregious anachronism in the book is its historical setting. From other historical texts both in and outside the Bible, we know that it was the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar himself who destroyed Jerusalem, burned the Temple and exiled the Jews; and that it was during the subsequent rule of the Persians that the Jewish exiles returned and rebuilt their Temple. Yet, according to Judith 4:3 and 5:18–19, the Jews had just recently returned from exile and rebuilt the Temple, and Nebuchadnezzar is threatening Jerusalem after the Jews have returned from exile and rebuilt the Temple. In other words, a pre-exilic event (that is, Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of the Temple and the exile of the Jews in 586 B.C.E.) is described in Judith in a post-exilic setting (that is, sometime after 519 B.C.E.). Even stranger, the Ammonite general Achior gives this account of Israelite history to the pre-exilic Nebuchadnezzar who, in the Judith narrative, will not succeed in destroying the Temple!

Geographical errors also abound. According to the book of Judith, Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Put and Lud (2:23) prior to his moving west across the Euphrates. But, again according to biblical and extra-biblical texts, these two countries are located in Africa (possibly Libya) and Asia Minor (Lydia?), respectively.

Here’s another goof: Nebuchadnezzar’s army travels from Nineveh to the plain of Bectileth in northern Cilicia (2:21), a distance of 300 miles, in three days! These are but the book’s more glaring historical and geographical errors.

Another reason sometimes suggested for Judith’s exclusion from the canon is the claim that it was written in Greek, rather than Hebrew. According to this view, the rabbis who met at Yavneh about 100 C.E. to decide what books would be included in the Hebrew Bible resolved to exclude from the canon apocalyptic and apocryphal works appearing in the Septuagint. The Septuagint is the third-century B.C.E. Greek translation of the Torah (the five books of Moses) made in Alexandria; additional holy books were later added to it. f;According to this view, books originally composed in Greek, which might include Judith, were especially objectionable.

There are at least two things wrong with this contention. First, it is based on a now outmoded understanding of how the “final” decision was made to include or exclude books from the Hebrew scriptures. Through the first half of the 20th century, the prevailing scholarly view was that shortly after the Roman destruction of the Jewish Temple and nation in 70 C.E., the rabbinic “synod” at Yavnehg (Greek: Jamnia), sometime around 100 C.E., finalized the canonization of the Hebrew Bible, closing the Jewish canon for all time.

But today, scholars5 put far less emphasis on Jamnia’s central role, arguing that there is a lack of evidence for it.h The canonization of the Hebrew Bible, scholars now say, was not an event, done once-and-for-all by an elite group of rabbis, but rather an extended process engaged in by the Jewish people. According to this view, much of the Hebrew Bible, in effect, had already been canonized before the Jamnia Council. Only the canonicity of a few biblical books (notably, Esther, Eccelesiastes and the Song of Songs) was still being debated by some Jews into the third or fourth century C.E.

Even more significant, it is highly debatable that the book of Judith was composed in Greek. Some apocryphal books once thought to be Greek compositions (Tobit and Ben Sira) have recently turned up in Hebrew fragments—Tobit at Qumran6 and Ben Sira at Masada.7 Moreover, internal textual evidence for a Hebrew Vorlage (original) is clear even in the extant Greek version of Judith.8 So the old, easy argument that the Council of Yavneh, about 100 C.E., omitted Judith from the Hebrew canon because it was composed in Greek is no longer persuasive.

Another reason sometimes suggested for the exclusion of Judith from the Hebrew canon is its late date. Unlike most of the canonical books, Judith was not written in what ancient Jews regarded as “the Golden Age” of Scripture, that is, before the days of Artaxerxes (465–426 B.C.E.). (In Describing the nature of the Jewish canon to his gentile readers, the first-century C.E. Jewish historian Josephus explained that “From Artaxerxes to our own time the complete history [of the Jews] has been written, but has not been deemed worthy of equal credit with the earlier records, because of the failure of the exact succession of the prophets.”)9

Scholars agree that despite the setting for the story of Judith in the early Achaemenian period (late fifth century B.C.E.), the book itself was composed, or at least redacted, in the Maccabean or, more likely, the Hasmonean period, in the late second or early first century B.C.E. Such a late date of composition would make it very difficult, but not impossible, for Judith to enter the canon. After all, the book of Daniel, at least in its final form, also dates to the very early Maccabean period (c. 167–163 B.C.E.).

Others have suggested theological “flaws” that might account for Judith’s exclusion. The conversion of Achior the Ammonite general to Judaism appears to be clearly contrary to Deuteronomy 23.3.

“No Ammonite…shall enter the assembly of the Lord…forever.”

In addition, sometime after 70 C.E. (when the temple and the Jewish state were destroyed by the Romans), the rabbis decided that a Gentile convert to Judaism had to be circumcised and baptized/immersed to become a Jew.10 Achior wasn’t!

Another factor may also have played a part in the book’s exclusion: It displays a most accepting attitude toward the towns of Samaria (Judith 4:4, 6; 15:4), and even makes a Samartian woman and her kinsmen the “saviors” of Jerusalem and its Temple. At the time the canonicity of this part of the Hebrew Bible was being decided upon, a great deal of hostility existed between Jews and Samaritans—clearly reflected in the Gospels of the New Testament, for example.

One scholar has suggested an anti-feminist explanation for Judith’s exclusion: Judith was simply too radical a woman for the males who determined the Hebrew canon:

“To accept the Book of Judith as a canonical book would be to judge the story holy and authoritative. And [that]…could indeed have been deemed a dangerous precedent by the ancient sages…[Judith] fears no one or thing other than Yahweh. Imagine what life would be like if women were free to chastise the leading men of their communities, if they refused to marry, and if they had money and servants of their own. Indeed if they, like Judith, hired women to manage their households, what would become of all the Eliezers [Genesis 15:1–6] of the world? I suspect that the sages would judge that their communities simply could not bear too many women like Judith.11

Another possibility is that Judith herself might have been considered to be morally flawed. To appreciate this argument, we need to bear in mind that Bible critics, like theater and art critics, inevitably reveal their own values and biases as they “objectively” comment on a particular work. This is surely true of commentators on Judith. When Christians found themselves mortally threatened by pagan persecutions, Christian scholars like Clement of Rome (30?–99? C. E.) regarded Judith primarily as a brave woman. Later, when sexual temptations to a celibate priesthood were more common than religious persecutions, many church fathers, like St. Fulgentius of Ruspe, emphasized Judith’s self-imposed celibacy:

“Chastity went forth to do battle against lust, and holy humility forward to the destruction of pride. [Holofernes] fought with weapons, [Judith] with fasts…Accordingly, a holy widow accomplished by virtue of chastity what the whole people of the Israelites were powerless to do” (Epistle 2:29).

In Victorian England, however, Judith was sometimes found wanting. According to E. C. Bissell, writing in 1886:

“The character [of Judith], moreover, is…objectionable from a moral stand-point…. Her way is strewn with deceptions from first to last…. She assents to [Holofernes’] request to take part in a carousal at his tent…. In fact, it would seem to have been a mere matter of chance that Judith escaped an impure connection with Holofernes…. Indeed, her entire proceeding makes upon us the impression that she would have been willing even to have yielded her body to this lascivious Assyrian for the sake of accomplishing her purpose…. And she exposes herself in this manner to sin, simply for the present purpose of gaining the confidence of a weak slave of his passions that she may put him to death…. There are elements of moral turpitude in the character of Judith.”12

More recently, we have been exposed to a Freudian understanding of Judith:

“Judith penetrates Holofernes’ camp rather than Holofernes penetrates her city…. The reference to the inability of the land to bear the weight of the invaders [7:4] would appear to be a thinly veiled sexual metaphor…. Not only did [Holofernes] not penetrate the narrow passage of the city, but he lost his head over a pretty woman, with the loss of his sword and head constituting symbolic castration…. The invaded becomes the invader…. The functional equivalent of a ‘virgin’ does not lose her maidenhead but rather she wins the head of the male oppressor.”13

Feminists sometimes see Judith not just as the warrior woman and the femme fatale combined, but as the archetypal androgyne, one who combines male and female characteristics.14 What makes Judith’s androgyny unusual, according to Patricia Montley, is that her “masculinity” and her “femininity” are sequential rather than simultaneous; that is, first Judith is asexual (the widow), then female (the seductress), next male (the executioner) and, finally, asexual (the life-long celibate).15

Like a sparkling diamond, Judith is many-faceted. Critics observe her from different angles and thus see quite different sides to her. Clearly, she doesn’t fit nicely into our conventional molds of saint or sinner, of masculinity or femininity. But of such diversity are literary gems made.

The author of the story tried to portray Judith as a saintly woman: “No one spoke ill of her, so devoutly did she fear God” (Judith 8:8). She devoted herself to constant prayer and fasting and observed the laws of kashrut. Her life was totally devoted to God and her people.

But if Judith was a “saint,” she was also a shameless flatterer (11:7–8), an equivocator (12:14, 18) and a bold-faced liar (11:10, 12–14, 18–19). She was also a ruthless assassin (13:7–8), with no respect for the dead (13:9–10, 15). Possibly Judith was omitted from the Jewish canon because of these “immoral” aspects of her character and actions. Some may even say she was guilty of murder. Ironically, Judith was a saint who murdered.

In the end, it may have been irony, a rhetorical device permeating the book,16 that accounts for Judith’s exclusion from the canon. This perhaps is what distinguishes it most clearly from the book of Esther.

The failure to recognize this pervasive irony may also account for the many misinterpretations of the book. A writer using irony often says exactly the opposite of what is really meant. A correct understanding is dependent upon the reader’s (or the character’s) appreciation of the Irony. When, for instance, Judith says to Holofernes that “my lord” will do this or will do that, Holofernes always understands her to be speaking of him; but the informed reader realizes that sometimes she is speaking of God, and that in those instances she is actually promising Holofernes evil things, not good (see Judith 11:5, 6, 11; 12:4, 14, 18).

Certain historical and geographical “errors” in Judith must also be deliberately ironical, especially in the book’s opening verse. Any author who knew as much Jewish history as he put in Achior’s mouth in Judith 5 had to know that Nebuchadnezzar was not king of Assyria and that his capital, was not Nineveh. With his opening verse, the author probably intended to alert his readers to the ironic character of his entire tale. C. C. Torrey suggested that a comparable modern opening for a story like happened at the time when Napoleon Bonaparte was king of England, and Otto von Bismarck was on the throne in Mexico…17 Needless to say, if the reader doesn’t see “the wink,” then much will be missed or misunderstood.

Consider a few of the other ironies that pervade the book:

•The Assyrian army, the conqueror of many great peoples and cities, is decisively defeated by the small town of Bethulia.

•The men of Bethulia cower behind their town walls while two unarmed women go out to do battle with the enemy.

•Achior tells Holofernes the absolute truth, only to be totally disbelieved; while Judith equivocates and shamelessly lies to Holofernes—and is believed!

•Wanting only to seduce the “helpless” widow, Holofernes ends up losing his head to her. Literally!

Judith herself is the most ironic. Although shapely, beautiful and wealthy, she lives an abstemious and celibate existence, filled with prayer and self-denial. Childless, she gives new life to her people. Judith not only prays for a deceitful tongue (9:13), but actually begs Israel’s merciful God for strength to cut off a defenseless man’s head (13:7). The ultimate irony is that this deeply religious woman became revered not for her piety but for killing. Judith was the saint who murdered for her people. Such ironies can fascinate one reader and repel another.

Why was Judith excluded from the Hebrew canon while the “godless” book of Esther was included? We will never know for sure. Probably there is no one reason. As in any election, voters cast their ballots for or against a particular candidate for different reasons, some valid, some not; so the sages of Israel and their followers in effect voted. Ultimately, the Jewish community determined that the book of Judith would not be included in its sacred scriptures.

Despite the exclusion of |Judith from the Hebrew canon, Judith herself remains a vivid personality, easily remembered from the many renderings of her grisly act created by artists over the centuries. Lost in the art, however, is the irony, humor, patriotism and piety that give the book of Judith its puzzling, yet intriguing and attractive quality.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

The listing of seven cities here is probably the author’s way of underscoring the totality of the capitulation to Holofernes, the number seven in the Bible being a symbol of completeness.

The name, yhwdyt, is generally understood to be Hebrew for “Jewess” and so would be an appropriate or allegorical name for the heroine. However, certainty on this matter is dened us because Esau’s Hittite wife had the same name (Genesis 26:34), and the male equivalent of the name, Jehudi, was borne by a foreigner in Jeremiah 36:14.

B.C.E. (Before the Common Era) and C.E. (Common Era) are the religiously neutral terms used by scholars, corresponding to B.C. and A.D.

In Daniel 3 and 6, Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon and Darius of Persia, respectively, did make such claims; but in these cases, most present-day scholars interpret the claims as symbols or veiled references to the detestable Syrian king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–163 B.C.E.).

It was through the Septuagint, rather than the Hebrew Bible, that the Christian Church came to know the Jewish scriptures.

Yavneh, nine miles northeast of Ashdod, is the site where the rabbis first assembled after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 C.E.

The words of David Noel Freedman are very apropos: “What do we really know about the Council of Jamnia? Everybody quotes everybody else about this famous or infamous Council, but what are the ancient sources, and what are the reasonable inferences about its activity? Personally, I think it was a non-event, and not much happened.” (Correspondence with Freedman.)

Endnotes

Judith’s canonical status, like that of other deuterocanonical books, was established by the Roman Catholic Church at the Council of Trent in 1546.

By contrast, the Protestants’ acceptance of Esther and their rejection of Judith is not puzzling, for Protestants include in their Old Testament only those books found in the Hebrew Bible.

For a discussion of this and related problems in the book of Esther, see my “Eight Questions Most frequently Asked About the Book of Esther,” BR 03:01.

Although God is not explicitly mentioned in Esther, God is assuredly referred to in Esther 4:14, where Mordecai says to Queen Esther, “For, if you persist in keeping silent at a time like this, relief and deliverance will appear for the Jews from another quarter; but you and your family will perish. It’s possible that you came to the throne for just such a time as this.” For a brief discussion of this verse, see my Esther: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, Anchor Bible 7B (Garden City: Doubleday, 1971), p. 50.

See, for example, Shaye J. D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1987), pp. 174–195, 226–231.

See J. T. Milik, “La Patrie de Tobie,” Revue Biblique 73 (1966), pp. 522–530. Four Aramaic texts of Tobit have also been found there.

Sirach 39:27–44:17 (see Yigael Yadin, The Ben Sira Scroll from Masada [Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1965]).

See my Judith: A New Translation With Introduction and Commentary, Anchor Bible 40, (New York: Doubleday, 1985), pp. 66–67.

For further details, see Harry M. Orlinsky, Essays in Biblical Culture and Bible Translation (New York: Ktav, 1974), pp. 279–81. But see Shaye J. D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, pp. 50–55, who points out that no Jewish text from the period prior to the destruction of the Temple knows of baptism/immersion as a required ritual of conversion.

T. Craven, Artistry and Faith in the Book of Judith, Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation Series 70 (1983), pp. 117–118. This is perhaps the best study, in any language, of the literary aspects of the Book of Judith.

E. C. Bissell, The Apocrypha of the Old Testament (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1886), p. 163.

Alan Dundes, cited in Luis Alonso-Schökel, “Narrative Structure in the Book of Judith,” Protocol Series of the Colloquies of the Center for Hermeneutical Studies in Hellenistic and Modern Culture XII/17 (March 1974), pp. 28–29. This is a remarkably insightful work, with contributions from a number of scholars, from a multi-disciplinary perspective.

Patricia Montley, “Judith in the Fine Arts: The Appeal of the Archetypal Androgyne,” Anima 4 (Chambersburg, PA: 1978), p. 39.