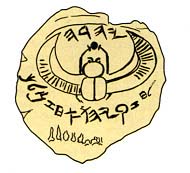

Some two years ago, Harvard professor Frank Moore Cross published an article in BAR that described for the first time an extraordinary lump of clay.a Known as a bulla, the clay was impressed with a seal belonging to King Hezekiah, who ruled Judah from c. 727–698 B.C.E. It was Hezekiah who saved Jerusalem from a siege by the Assyrian monarch Sennacherib by fortifying and expanding the city’s walls and by building the tunnel that still bears his name to ensure a steady supply of water.b And it was he who instituted a major religious reform in which he sought to centralize worship in Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, eliminating the shrines and sacred pillars in outlying areas of the country, by then divided into the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. Indeed, as we shall see, Hezekiah even wanted to reunite the country again, as in the days of David and Solomon.

The inscription on the seal, written in the kind of Hebrew letters used before the Babylonian Exile, reads, according to Cross:

לחזקיהו•אחז•מלך•/יהדה (

ḷhzqyhw ’̣hz mlk/yhdh )[Belonging] to Hezekiah [son of] ’Ahaz, king of / Judah

The seal, as impressed in the bulla, is extraordinary not only because it belonged to a well-known Judahite king, but also because it is iconic; that is, in addition to the Hebrew inscription, it shows a picture; in this case a carving of a two-winged beetle pushing a ball of mud or dung.

What in the world is a two-winged dung beetle doing on a seal of a Hebrew king? Its appearance, especially on a royal seal, begs for interpretation. Cross associates it with Phoenician iconography. The importance of the matter is reflected in the title of his article: “King Hezekiah’s Seal Bears Phoenician Imagery.”

The question is indeed important, as I shall explain, but I believe Cross gave the wrong answer. The image is a direct borrowing from Egyptian iconography and can be understood as an adaptation by the great Judahite king to advance his own national agenda.

Cross recognizes that the iconography of the dung beetle (also called a scarab) originated in Egypt. But it was appropriated by the Phoenicians, along with much other Egyptian art, as is widely accepted. Thus many Phoenician seals are scarab-shaped and we find many Egyptian motifs, including the dung beetle, in Phoenician decorative art. From the ninth century B.C.E. on, Egyptian symbols became widespread in Phoenicia as earlier local traditions receded and were forsaken.1

But this does not answer the question as to whether Hezekiah got it from the Phoenicians or more directly—from the Egyptians. In my view, the fact that the beetle symbol appears in both Phoenicia and Judah does not mean that the latter imitated Phoenicia, but rather that each independently developed its own distinguishing features based on the original source—Egypt. Transient Egyptian craftsmen transmitted their versatile skills in the arts and crafts over wide areas simultaneously in Phoenician and Judahite circles.2 Consequently, Hebrew artisans not only emulated Phoenico-Egyptian art, but also copied Egyptian art directly.3

Fortunately, there are enough unique stylistic details to allow us to determine whether the decoration on Hezekiah’s seal represents a borrowing from a Phoenician adaptation of an originally Egyptian icon or a direct borrowing from Egyptian prototypes. As one leading Egyptologist has observed, “The style of the artifact determines whether it is Egyptian or perhaps a Phoenician imitation of the [Egyptian] original.”4

Beetles were a popular motif in ancient art and were depicted in several ways, including wingless, two-winged and four-winged. In the case of Hezekiah’s bulla, the seal cutter fashioned a two-winged scarab, based on the Egyptian prototype. Egyptian artists produced only two-winged beetles.5 Phoenicia, in its adaptation of this Egyptian motif, developed the four-winged variety.6 The four-winged beetle of Phoenicia, however, is not comparable to the two-winged beetle of Egypt.7

The predecessor of the winged beetle in Egyptian iconography and imagery was the winged sun-disk. Known as the Great Winged Disk, its literal meaning in Egyptian (‘py wr) is the “Great Flier.”8 It is closely linked to Horus, god of the horizon, who is portrayed as a falcon.

Eminent Egyptologists explain the symbol of the winged sun-disk as an artistic expression of the Egyptian kingdom united under divine providence; the two wings represent Upper and Lower Egypt.9 As early as the Vth dynasty (c. 2498–2345 B.C.E.), the image of the winged sun-disk was accompanied by the phrase

The winged sun-disk also represented the pharaoh as Horus incarnate, hovering over the two halves of Egypt.11 In some instances, the winged sun-disk is defended by the two uraei (snakes), each of which faces a wing and often also wears a crown of either Upper or Lower Egypt.12 In later Egyptian imagery, Horus is often represented as a winged beetle,13 as in this inscription on the Ptolemaic-era Edfu Temple to Horus:

“You are the youth that emerged as the doer of beneficent acts,

Who served as the beetle who renews the birth of royal crowns.”14

When the beetle, or scarab, as it is often called, replaces the sun-disk, a ball carried by the beetle represents the daily rising solar ball that the sun god rolls from east to west. The name

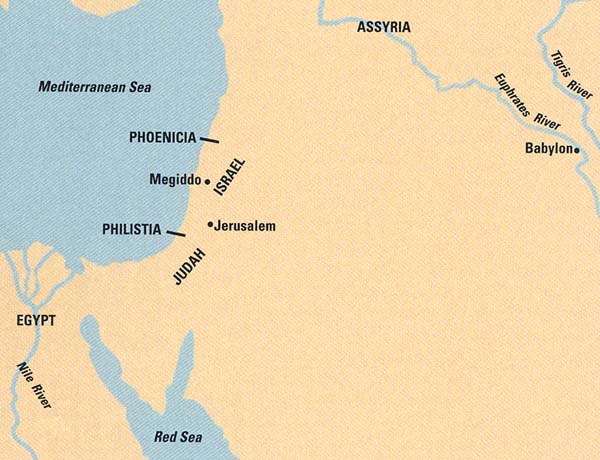

What, then, did Hezekiah wish to convey by selecting an Egyptian symbol for his seal? His message becomes evident when seen in the political context of his reign. Shortly after his reign began (c. 727 B.C.E.), the northern kingdom of Israel fell to the Assyrians (in 721 B.C.E.). The remainder of his reign (until c. 698 B.C.E.) was marked by his unrelenting efforts to entice the remaining Israelites who fled from the north to join forces with him in order to restore the unified kingdom (2 Chronicles 30:1, 6–11, 18, 25; 31:1, 5–6).17 To a certain extent he succeeded in re-establishing some of the grandeur of King Solomon’s time (2 Chronicles 30:26). He earned the respect of his neighbors (2 Chronicles 32:23) and became one of the leading forces in the rebellion against Assyria. His political alliance with the Egyptian Cushite dynasty demonstrated a daring challenge to Assyrian hegemony in the region and also reflected his direct ties with Egypt.18

Isaiah, prophet and confidante of Hezekiah, often alludes to Egyptian cultural ideology in his oracles.19 He even refers to Egypt as “land of the beetle with wings” (Isaiah 18:1).20 Much material confirms mutual contacts between the people of Judah and Egypt.21

Against this backdrop, I believe that Hezekiah consciously chose the Egyptian design, laden with symbolic content, to promote his own lofty ambitions. He borrowed the beetle icon from his southwestern neighbor and ally to convey the concept of permanence. The ball the beetle pushes represents the rejuvenation of the kingdom; the set of wings signifies the unification of the north and south of the Land of Israel under a scion of the House of David, just as they characterized the union of Upper and Lower Egypt under the pharaoh.22 The seal, then, expressed the desire for the political renaissance of a united Israel. It harmonized perfectly with Hezekiah’s fervent hopes for an eternally united kingdom.

In this way, the scarab was stripped of its Egyptian religious iconography and instead donned the mantle of a national banner. The double-winged beetle symbol unfurled the flag of Judah’s official policy and as such it was adopted as a kind of coat of arms. One scholar has recently characterized the two-winged scarab motif in Judah as “a royal emblem.”23

The idea is reinforced when the seal is read exactly as written. Even though Cross correctly deciphered the ancient Hebrew words, he did not present them in the order they appear on the seal. A perusal of Nahman Avigad’ Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals shows that the seal cutters engraved inscriptions in one of three ways: either from top to bottom, usuallywith dividers between the words, clockwise around the icon or on both sides of the icon. This seal does not follow any of these patterns. Is it flawed or deliberate? Stylistically, it combines two patterns, reading from top to bottom beginning with a single word on the top and continuing on the lower half with a phrase written in semicircle rather than straight across. The single word, yhdh, Judah, is seperated from the rest of the inscription by the body of the beetle and is embraced by its two wings. Conceptually it has a unique message. The name of the country is prominently placed, signalling its renewed status. The bottom phrase identifies the owner, “belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz king.” THe last word affirms Hezekiah as ruler. Accordingly, the inscription should read as follows:

Judah/Belonging to Hezekiah, son of Ahaz, King!

Not only does the bottom part provide patronymic details, but it also proclaims regency. Hezekiah, whose father was a vassal of Assyria, proudly features the name of his strengthened country after he had vanquished the Philistines (2 Kings 18:8) and emphasizes his elevated position as an independant king following the rebellion against Sennacherib, king of Assyria (2 Kings 18:7).

While we are not accustomed to the novel ending “king” on seal impressions, it was not unusual in Egypt. A common titular address of an Egyptian ruler was

This meant: Pharaoh, may he live and prosper and enjoy good health, the king!

To return to the question of why a Judahite king would employ Egyptian imagery, we saw that the insignia had political significance. But, besides its Egyptian-inspired symbolism, did it incorporate any Judaic values? Did the seal cutter choose a pattern for the beetle’s wings at random or did he deliberately select a particular motif? The beetle’s wings could have been portrayed in one of three ways: a horizontal position, tipped down or tipped up. The artist chose neither the hieroglyphic ideogram of the beetle with wings in a horizontal form25 nor the image of the double-winged solar disk with down-turned wingtips26 that he might have seen on the seal of Pharaoh Taharqa, the political contemporary of Hezekiah.27 These two depictions are consonant with the Egyptian view of a divine pharaoh who hovers over the Two Lands. The Egyptian artist, therefore, presents a royal god incarnate in the ruler, sheltering, with his wings, his subjects below him. In contrast, Hezekiah’s royal seal cutter chose the third model, a beetle whose double wings are upswept, as in the image of the anthropomorphic sun god Khopri.28 He picked a design that suited his king’s religious beliefs: The Judahite king did not view himself as a deity but rather as a human who gazed aloft to the God in heaven for deliverance.29

Hezekiah was succeeded by his son Manasseh. A seal inscribed “[belonging] to Manasseh son of the king” may be Manasseh’s seal before he ascended to the throne.30 The seal, like Hezekiah’s, also bears a depiction of a two-winged beetle with a ball between its forelegs.31 In this way, the message of the icon and its symbolism was passed on to an additional generation.

Manasseh’s name itself figures in the case I am building. Hezekiah did not chose a name for his son containing a Judaic theophoric element, like YW (yo-) or YH (-yah) or YHW (-yahu), all signifying the personal name of the Israelite God YHWH, as was so common among the kings of Israel and Judah (examples include Yotham [often spelled Jotham] and even Hezekiah itself [Hizqiyahu and Hizqiyah in Hebrew]). Instead he chose a name that originated on Egyptian soil. Manasseh was the name Joseph gave to his own firstborn—from his “Egyptian wife, daughter of the priest of ‘Ôn” (Genesis 41:50–51), hence a grandson to an Egyptian

It is worth noting that a number of other Hebrew seals of Hezekiah’s era display Egyptian motifs that would hardly have come from Phoenicia. For example, one seal displays a winged sphinx, wearing a kilt and double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. In front of the sphinx is a large ankh.32 Another seal displays a very Egyptian-looking winged sun-disk.33 Another seal with a Hebrew inscription includes the bust of the Egyptian lion-headed goddess Sekhmet.34 And of course the two-winged beetle appears several times.35

Cross implies that the two-winged beetle on Hezekiah’s seal reflects a religious view: “There appears to have been a tendency to solarize Yahweh in Judah in the eighth century [B.C.E.] and later,” he tells us. But this would surely not be true of Hezekiah. His allegiance solely to the God of Israel was unquestioned: “He trusted only in the Lord God of Israel. There was none like him among all the kings of Judah after him, nor among those before him” (2 Kings 18:5). It was Hezekiah who instituted a religious reform that centralized worship in Jerusalem, abolishing outlying shrines and smashing the sacred masseboth (standing stones) (2 Kings 18:4). It is unthinkable that Hezekiah had Egyptian theology in mind when he commissioned this seal.

To interpret Hezekiah’s seal Cross draws on the late fifth- or fourth-century B.C.E. prophet Malachi to support his view that the two-winged beetle, like the winged sun-disk, imparts a religious significance. For Cross, the winged sun-disk is “a symbol of the deity bringing salvation,” like the winged scarab pushing a ball of dung, which in his view signifies the ever-renewing movement of the sun. Cross invokes the words of Malachi:

“For you who revere my Name, the sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings” (Malachi 4:2; Malachi 3:20 in the Hebrew Bible).36

Reliance on Malachi, in my view, is inapt, to say the least. In the first place, the wings on Hezekiah’s seal are attached to a scarab, not to a sun-disk. Malachi’s poetic oracle mentions only the sun in conjunction with wings, not with a beetle. Moreover, a prophet of the fifth-fourth century B.C.E. is an implausible source from which to decode eighth-seventh century B.C.E. iconography. If the analogy suggested by the prophet had been drawn from a source outside ancient Israel, Malachi would have chosen motifs from art and religion of the dominant culture of the time: Persia. Indeed, we do have examples of the Persian deity Ahura Mazda rising from a winged sun-disk.37 Such decorations were widespread during the reign of the Persian kings and even reached Thebes, the cradle of sun worship.38 Surely Malachi’s metaphor has no connection to the winged beetle on Hezekiah’s seal.

Cross is correct that beetle iconography disappears from Judah relatively early.39 His reasons seem to me inaccurate, however. Cross reasons that the religious reforms of the Judahite king Josiah in the late seventh century B.C.E. were more rigorous and uncompromising in their aniconic (without images) thrust than those of Hezekiah. Indeed, the break with the past during Josiah’s reign was uncompromising, but figurative art on seals was not necessarily directly affected by his religious reforms. As one prominent expert on ancient seals has remarked, “It seems impossible to understand the growing tendency of aniconism displayed by late Judean private seals as the result of a direct implementation of the biblical veto on cultic images.”40 Instead, the waning of the beetle as a royal emblem as well as the decline in use of Egyptian pictorial designs on official (and private) seals was intentional—the result of a shift in Judahite foreign policy. Josiah had a completely different political orientation than Hezekiah. Instead of aligning himself with Egypt, Josiah saw the rising Babylonian empire as the dominating force of the future.41 He wisely sought to distance himself and his country from Egypt. His foresight was justified, as later events showed. Unfortunately, Josiah was killed in a battle at Megiddo that sought to block the Egyptian army from marching to northern Syria. Once Josiah fell, the dream of a reborn Solomonic kingdom, nurtured by his great-grandfather Hezekiah, was laid to rest. In these circumstances, the Egyptian symbol of a two-winged beetle was not only unappealing; it was also quite politically incorrect.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Cyrus H. Gordon, my teacher, with whom I discussed this bulla. “A [deceased] scholar, in whose name a tradition is reported in this world, his lips move gently in the grave” (Babylonian Talmud, Yebamoth 97a).

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Frank Moore Cross, “King Hezekiah’s Seal Bears Phoenician Imagery,” BAR 25:02.

See William Shea, “Jerusalem Under Siege,” BAR 25:06 and Mordecai Cogan, “Sennacherib’s Siege of Jerusalem,” BAR 27:01.

Endnotes

Enrico Acquaro, “Scarabs and Amulets” in Sabatino Moscati, ed., The Phoenicians (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), pp. 394–403. See also Moscati, “Arts and Crafts,” Phoenicians, pp. 244–247. Without minimizing local influences, the striding sphinx, the woman at the window and the Nimrud bowls show a “preponderance of Egyptian or Egyptianizing motifs.” See John E. Curtis and Julian E. Reade, eds., Art and Empire (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 135. See also Richard D. Barnett, “Layard’s Nimrud Bronzes and Their Inscriptions,” Eretz Israel 8, pp. 1–6. Further, Samarian ivories decorating the Ivory Palace of Ahab (1 Kings 22:39) and his Sidonian Queen Jezebel are closer in spirit to the Egyptian representations that inspired them than other ivories brought from neighboring localities. See Maria Luisa Uberti, “Ivory and Bone Carving,” in Moscati, The Phoenicians, p. 412.

Skilled artisans are among the categories of people cited by Homer’s Odyssey (chapter 17, pp. 382–386), as welcomed the world over. For a detailed discussion, see Cyrus H. Gordon, “Ugaritic Guilds and Homeric Demioergoi,” in Saul S. Weinberg, ed., The Aegean and Near East: Studies Presented to Hetty Goldman (Locust Valley, NY: J. J. Augustin, 1956), pp. 136–143. The mobility of the artisan guilds is also discussed in Walter Burkert, The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1992), pp. 6, 8.

John H. Currid, Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1997), p. 170, notes 55–59.

This is my translation. Raphael Giveon, Footsteps of Pharaoh in Canaan (Tel Aviv: Sifriat Poalim, 1984), p. 112 [Hebrew]. For the Phoenician aspect, see Cyrus H. Gordon, “The World of the Phoenicians,” Natural History 75 (1966), pp. 14–23.

See Ruth Hestrin and Michal Dayagi-Mendels, Seals from First Temple Period: Hebrew, Ammonite, Moabite, Phoenician and Aramaic (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1978), p. 53 [Hebrew].

The proximity of production dates led Cross, in his BAR article, to compare the icon on the Hezekiah bulla with the four-winged beetle on a Phoenician bowl, also from the Moussaieff collection. Raphael Giveon finds that the four-winged motif originated in the Mitanni Kingdom and was later absorbed into Phoenician art. (Giveon, Footsteps of Pharaoh, pp. 140–4 [Hebrew]). Nahman Avigad assumed that the Hebrew artisans adopted the four-winged scarab from the Phoenicians who had used Egyptianized themes. He admits, however, that the “two-winged scarab and the two-winged uraeus of Egypt [my emphasis] were often depicted as four-winged on Hebrew seals.” Nahman Avigad, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1997), p. 45.

Both two-winged and four-winged flying beetles with or without a solar disk were found in Jerusalem on jar handles during the period of Hezekiah. Almost all—60 out of 61—of these l’melekh (“belonging to the king”) seals were of the two-winged variety. Very few of the four-winged type were discovered. A.D. Tushingham, an expert in lmlk seals, maintains that the latter was the royal symbol of the Northern Israelite kingdom. Although rarely found on lmlk jars, the four-winged beetle was absorbed as a symbol by Judah, which already had the two-winged scarab as its royal symbol, because of King Hezekiah’s insistence that he was the legitimate heir to the defunct Northern Kingdom. This iconography was not original, but derived from Phoenicia, with which the Israelite dynasties had close ties. See A. D. Tushingham, “New Evidence Bearing on the Two Winged LMLK Stamp,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 287 (1992), pp. 61–64.

The two-winged icon, either alone or with the solar disk, emerged from a version of the old Egyptian solar disk motif that was prevalent in the entire Levant during the monarchical era. The origin of the two-winged variety of lmlk cannot be determined because the prototypes were crude representations with clumsy inscriptions.

Raymond Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian (Oxford: Griffith Institute, 1986), p. 41. For the story of the winged sun-disk see Alfred Wiedemann, Religion of the Ancient Egyptians (London: H. Greuel, 1897), pp. 69–80. See also Herbert W. Fairman, “The Myth of Horus at Edfu,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 21 (1935), pp. 26–36. See Alan H. Gardiner, “Horus the Be

Kurt Sethe, Urgeschichte und alteste Religion der Ägypter (Leipzig: Nendeln, 1930; Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1966) pp. 155ff. See also Gardiner, “Horus,” pp. 46–52.

Gardiner and T. Eric Peet, The Inscriptions of Sinai (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1952), Plate VI, no. 10.

“Winged Sun-disk,” in Wiedemann, p. 75, fig. 14. See also Richard H. Wilkinson, “The Sphinx Stela of Thutmose IV in Giza,” in his Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994), pp. 152–153, Illus. 106. Usually, the sun god has only one uraeus for his protection. See also Gardiner, “Horus,” p. 48, n. 2, p. 50, fig. 3.

Gardiner, “Horus,” p. 53. See also Erman and Grapow, Wörtenbuch, 1.178 no. 11 and 10.179 no. 22.

Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar, 3rd ed. (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1973), p. 584. Also, E.A. Wallis Budge, The Egyptian Book of the Dead (New York: Dover, 1967), cix–cx, p. 246 n. 2. For an explanation of

Giveon explains the relationship between the sun god and the dung beetle in Egyptian Scarabs From Western Asia From the Collections of the British Museum (Freiburg: University Press, 1985), p. 9.

Hezekiah is described as a king with impeccable behavior by the Chronicler. For a discussion of the aim of the Chronicler, see David N. Freedman, “The Chronicler’s Purpose,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 23 (1961), pp. 436–442 and Isaac Kalimi, The Book of Chronicles Historical Writing and Literary Devices (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 2000), p. 31 [Hebrew]. For an explanation of the diverging accounts of Kings and Chronicles see M. Breuer, “Torat ha-Teudot shel ba’al Sha’agat Aryeh,” Megadim 2 (1986), pp. 9–22 [Hebrew].

2 Kings 18:21, 19:9; Isaiah 36:6, 37:9, 17–22. The weakness of the Egyptian ally, however, is demonstrated by his failure to send help to Hezekiah, who was under siege in his capital. See Douglas J. Brenner and Emily Teeter, Egypt and the Egyptians (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1999), p. 50. Compare Antony Spalinger, “The Concept of Monarchy During the Saite Epoch—An Essay of Synthesis,” Orientalia 47 (1978), p. 24. See also Hayyim Angel, “Differing Portrayals of Hezekiah’s Righteousness: Narratives and Prophecies,” Nachalah: Yeshiva Univ. Journal for the Study of Bible (1999), pp. 1–13. For Egyptian ties, see pp. 5 and 8.

Judeans during the time of Hezekiah were aware of Egyptian culture and symbols. See Sarah Israelit-Groll, “The Egyptian Background to Isaiah 19:18, ” in Meir Lubetski et al., eds., Boundaries of the Ancient Near Eastern World: A Tribute to Cyrus H. Gordon (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), pp. 300–303; Meir Lubetski and Claire Gottleib, “Isaiah 18: The Egyptian Nexus,” Ancient Israelite Religion, pp. 364–384; Kenneth A. Kitchen, “Late Egyptian Chronology and the Hebrew Monarchy,” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Studies 5 (1973), pp. 225–233; Currid, Ancient Egypt, pp. 229–246; Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1992), p. 351.

This is my translation, published in Lubetski et al., Boundaries. See also Lubetski, “Isaiah 18:1: Egyptian Beetlemania,” in Jewish Studies in a New Europe: Proceedings of the Fifth Congress of Jewish Studies in Copenhagen 1994 under the Auspices of the European Association for Jewish Studies (Copenhagen: C.A Reitzel Publishers and the Royal Library, 1998), pp. 512–520.

A successful struggle for the reunification of Upper and Lower Egypt under one monarch takes place toward the end of the seventh century B.C.E. See the relevant Egyptian sources in James H. Breasted, ed., Ancient Records of Egypt IV (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1906), pp. 452, 454. Neferkara Shabako, the Nubian pharaoh of the XXVth dynasty who unified Upper and Lower Egypt, commemorated his achievements on a scarab; see J. Yoyottee, “Plaidoyer pour l’authenticité de scarabée historique de Shabako,” Biblica 37.4 (1956), pp. 457–476. Possibly Hezekiah emulated Shabako by symbolizing his attempted unification of Israel and Judah with a scarab seal.

Robert Deutsch, Messages From the Past (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications, 1999), p. 51. It is important to mention the cubic bronze weight in the British Museum (WA119433) on which a two-winged scarab is portrayed and is thought to be the royal symbol of the Kings of Judah. Curtis and Reade, Art and Empire, p. 195. Yigal Yadin already suggested in 1965 that the symbol of the four-winged beetle served as the royal insignia of the Judean monarchy: “A Note on the Nimrud Bronze Bowls,” Eretz-Israel, 8:6 and n. 1 and 2. He passed away before the information about the two-winged beetles appeared.

Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar, p. 75, n. 10. Further evidence of this style, where an inscription surrounds an icon and the phrase ends with a royal title, can be found as follows: A scarab from the period of the New Kingdom found in Tell el Ajjul reads

See Max E.L. Mallowan, Nimrud and Its Remains, vol. 2 (London: Collins, 1966), p. 599, fig. 583. For additional scarab objects belonging to the Egyptian Saite period see pp. 437–41, 472, and p. 645 n. 96.

Did the vision of the cherubim’s wings that spread upward in the Tabernacle (Exodus 25:25, 2 Kings 6:27) play a role in the design of the wings? Note the view of the rabbis in the Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 5b. For illustrations of cherub wings from the ninth century B.C.E. see Elie Borowski, “Cherubim: God’s Throne?” BAR 21:04.

Some have suggested that the seal is a forgery. As Avigad noted, the problem is that Manasseh ascended the throne when he was just 12 years old. Would he have had a seal before then? He may have had property of his own despite his young age or the seal could have been used by the custodian of his property. See Avigad, “The Contribution of Hebrew Seals to the Understanding of Israelite Religion and Society,” in Patrick D. Miller et al., eds., Ancient Israelite Religion: Essays in Honor of Frank Moore Cross (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987).

See Robert Deutsch and Michael Heltzer, New Epigraphic Evidence from the Biblical Period (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publication, 1995), p. 59,(no. 63 [8]).

The translation is quoted from the article in BAR. Cross cites the verse as Malachi 4:2, which is based on the Septuagint. In the Masoretic Text the verse is 3:20. Cross, in his note 8, acknowledges Lawrence Stager for bringing to his attention the verse and its meaning. However, the meaning of this verse is not at all clear. Witness the plethora of explanations to the phrase in Andrew E. Hill, Malachi, Anchor Bible Series, 25D (New York: Doubleday, 1998), pp. 349–350. See also Mordecai Zer-Kavod, Minor Prophets (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1970), Malachi 3:20, n. 58. [Hebrew].

Porada, Ancient Iran, p. 154, fig. 84. See also an Achaemenid cylinder seal bearing the name of Darius and portraying Ahura Mazda rising from a winged disk on p. 176, fig. 89.

Avigad already observed that the Hebrew seal cutters produced more glyphic seals in the eighth century B.C.E. than their seventh-century counterparts. There is a 4:1 ratio between the iconic seals of royal officials in the eighth century B.C.E. and the iconic seals, bullae and seals dating to the end of the seventh century B.C.E. See “Seal,” Encyclopedia Biblica (Jerusalem, 1958), pp. 67–86 [Hebrew]; Hebrew Bullae from the Time of Jeremiah (Jerusalem: Israeli Exploration Society, 1986), p. 118.

Christoph Uehlinger, “Northwest Semitic Inscribed Seals, Iconography and Syro-Palestinian Religions of Iron Age II: Some Afterthoughts and Conclusions,” in Benjamin Sass and Uehlinger, eds., Studies in Iconography of Northwest Semitic Seals, pp. 257–288, esp. pp. 278–288; Sass, “The Pre-Exilic Hebrew Seals: Iconism vs. Aniconism,” in Sass, Studies., pp. 194–256, esp. pp. 196–199 and 243–245.

Yehudah Kil describes in detail the intentions of the king in going to battle with the Egyptians in 2 Kings (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1989), pp. 802–804 [Hebrew]. See Kil, 2 Chronicles (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1986), pp. 924–925 [Hebrew]. In fact, contacts with Babylonians already had begun during the reign of Hezekiah. (See 2 Kings 20:12–19; Isaiah 39:1–8.)