I remember it vividly. It was September, 1991. I was a new, although not exactly a young, scholar, still working toward my master’s degree at Tel Aviv University. Professor Benjamin Mazar, the doyen of Israeli archaeology and former president of Hebrew University, invited me to a salon he regularly held in his apartment. In attendance was the most illustrious scholar of ancient epigraphy at Hebrew University, Professor Nahman Avigad, as was the distinguished epigraphic au-thority and my friend and mentor, Professor Michael Heltzer of Haifa University. Naturally, the discussion focused on a set of new inscriptions that were coming to light, the most exciting of which were included in a hoard of bullae (singular, bulla)—flattened lumps of hardened clay bearing seal impressions—that Professor Avigad had published in his 1986 book, Hebrew Bullae from the Time of Jeremiah: Remnants of a Burnt Archive.a Toward the end of the afternoon, I recall Professor Avigad, who was already an old man, wistfully expressing the hope that before he died he would see a seal or seal impression of a Judahite king.

Unfortunately, Professor Avigad went to his grave the following January at the age of 86, b not knowing that he had indeed seen the seal impression of one of the most important Judahite kings, Hezekiah, who ruled from 727 to 697 B.C.E. In the Bible, Hezekiah is celebrated for purging the Judahite religion of foreign influence, centralizing the cult in Jerusalem and withstanding a siege of Jerusalem by the Assyrian monarch, Sennacherib. Archaeology has also revealed much about Hezekiah’s reign.c One of the bullae in the hoard that Avigad had published in 19861 (bulla 1) was, in fact, impressed with the seal of that great Judahite king. But Avigad didn’t recognize it.

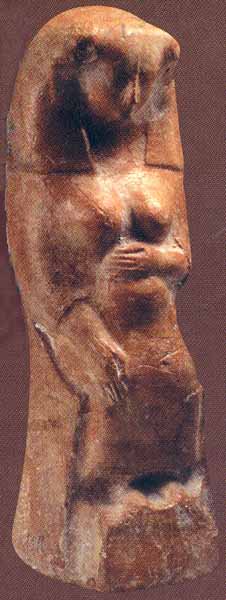

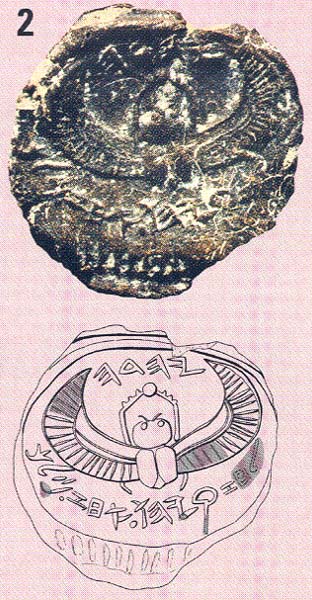

Avigad cannot be faulted, however. The seal featured a two-winged scarab (dung beetle) pushing a ball of mud or dung. But in the impression, only four letters of the seal owner’s name had survived: the Hebrew letters nun, yod, he and waw, that is, nyhw. The last three of those letters formed a very common name-ending, yahu, a form of the divine name Yahweh, the personal name of the Israelite God. But of the first part of the seal owner’s name, only one letter was left, a nun, or n, and so Avigad guessed that the name on the seal was Adoniyahu. In fact, part of the letter that Avigad took for a nun was not entirely preserved; it was actually a qof, or q. The preserved letters on the seal were not nyhw but qyhw, which spell the end of Hezekiah’s name in Hebrew, H

We now know what Avigad could not know, because a new crop of bullae bearing impressions of Hezekiah’s seal has been making its way into public view from the antiquities market since the mid-1990s. Some of these bullae are being published here for the first time.

The first one that I was able to inspect (bulla 2, above) came into my hands in 1997.2 Enough of the inscription had survived in this bulla that its inscription could be read: “Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz, king of Judah.” That same year I mentioned this more complete bulla of Hezekiah’s seal in my book, Messages From the Past;3 in 1999 Professor Frank M. Cross of Harvard University published it in BAR.d The impression on this bulla is so similar to the one on Avigad’s bulla that Professor Cross (and I, initially) thought that both bullae were made from the same seal. After a closer examination, however, I have concluded that they must have been made from different seals, because the bullae differ very slightly. For example, look at the left wing of the bulla that Avigad published (bulla 1): A single line appears above the cross-hatching on the upper edge of the wing. Now compare that with the wings of the scarab in the bulla published by Frank Cross (bulla 2). Above the cross-hatched wings, especially discernible on the right wing, are two lines. The seals from which the impressions were made are extremely similar, but not identical. The court functionaries who sealed royal documents must have had more than one copy of the king’s seal.

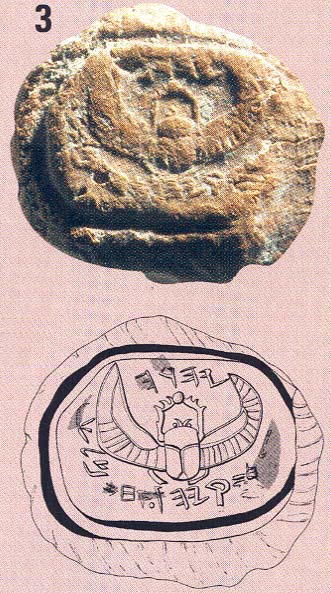

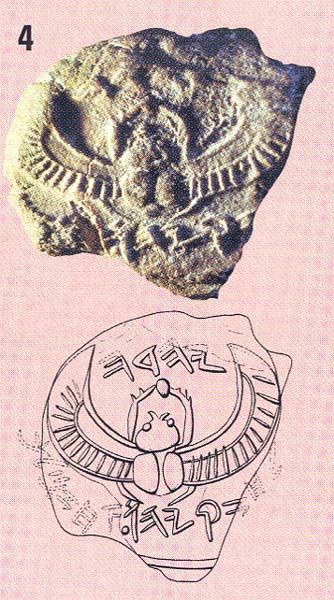

If the two bullae were impressed by different seals, can we indeed complete the missing letters on the Avigad bulla with the name of Hezekiah from the Cross bulla? As it happens, we can, thanks to three previously unpublished bullae (two of which are shown in this article) that have very recently been made available. One of the seal impressions (bulla 3, above left) was slightly crushed before it dried and hardened, unfortunately leaving both the image and the inscription incomplete. But enough is legible to confirm that it was made by the same seal4 that produced the bulla that Avigad could not recognize as belonging to Hezekiah. The second of the three bullae (bulla 4, above right) is well preserved but not fully impressed.5 A third one, which I have seen but which is not shown here, is in excellent condition and leaves no doubt that it bears the very same seal as Avigad’s—and its inscription reads “Belonging to Hezekiah (son of) Ahaz, King of Judah.” I can offer neither a picture nor a drawing of it, because it is being marketed by an antiquities dealer.

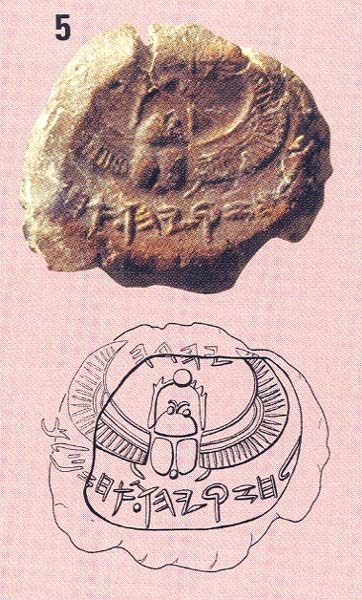

The current cache of new bullae also includes yet another example of Hezekiah’s seal that has the two lines above the wings (bulla 5, below). It too is being published here for the first time.6

Thus we now have a total of six bullae, each of which has a two-winged scarab and the identical inscription: “Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz, King of Judah.” Four have one line and two have two lines above the wings.

A new surprise emerged with two other recently unveiled bullae that are inscribed with Hezekiah’s name but have an entirely different royal emblem. Instead of a two-winged scarab, the seals feature a two-winged sun disk. Six rays shoot out of the top and bottom of the sun disk and two downward-curving wings project from the sides (unlike the upswept wings on the seals with a scarab). On either side of the disk is an Egyptian ankh, a symbol known as “the key of life.”

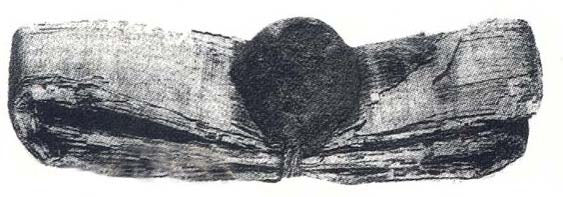

Both bullae are made from the same seal. One is in excellent condition;7 the other, much less so.8 The well-preserved bulla (shown at the beginning of this article) is made of black clay and has a complete seal impression. Like most bullae, it is tiny—barely a half-inch wide and even less than that in height.9 A deep groove around the edge indicates that the seal was probably originally set in the metal bezel of a ring.

Above and below the two-winged sun disk is an inscription identical to that appearing on the Hezekiah bullae with the two-winged scarabs:

hdhy ûlm zJa whyqzJl lh

zqyhw ‘h z mlk yhdh Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz, King of Judah.

So now we know that Hezekiah had at least two royal emblems: the two-winged scarab and the two-winged sun disk.

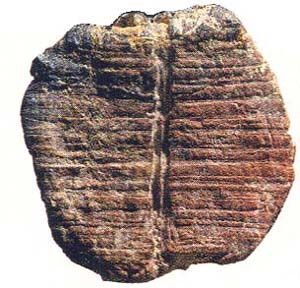

This should not surprise us, given what we have seen on nearly 4,000 so-called l’melekh jar handles that have been firmly dated to Hezekiah’s reign.10 Before being baked, these clay storage jar handles were impressed with a stamp seal containing an icon and an inscription, much like the other royal seals we have been discussing. Each jar handle inscription begins with the word l’melekh, which means “Belonging to the king.” Following this designation of the king’s ownership is the name of one of four cities, each of which was probably an administrative center.

The icons on these l’melekh handles vary. Some bear a four-winged scarab. Others have a two-winged sun disk with six rays that is similar to one on the newly revealed bullae impressed with Hezekiah’s name. (No l’melekh handles show scarabs with two wings.) I wouldn’t be at all surprised if someday we also find a seal or bulla of Hezekiah that has a four-winged scarab on it!

Long ago, Yigael Yadin (1917–1984), one of Israel’s pre-eminent archaeologists, asserted that the l’melekh stamps represent royal emblems.11 Some scholars doubted this—but these bullae end the debate and prove Yadin correct. We now know that Hezekiah had at least two royal emblems, which appear both on royal seals and on jar handle seals dated to his reign.

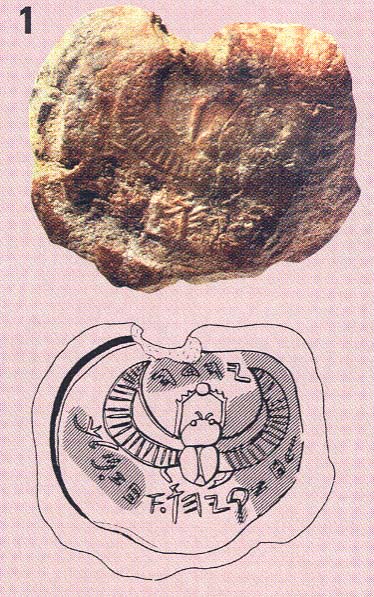

Hezekiah seems to be the first Judahite king to adopt a royal emblem with an icon on it. A seal impression bearing the name of Hezekiah’s father, King Ahaze (735–725 B.C.E.), is aniconic: It has no royal symbol, only an inscription.12

Why would King Hezekiah, acclaimed in the Bible for his elimination of foreign influences from Judahite cult practices, adopt Egyptian iconographic elements—elements that were both foreign and pagan—as his royal emblems?

This is a topic of intense debate. Frank Cross argued in BAR that although Hezekiah’s two-winged scarab was an Egyptianized icon (that is, one created by non-Egyptians to look Egyptian), it was really mediated through Phoenician iconography.f Meir Lubetski took Cross to task for this in a later issue of BAR,g arguing that Egypt, not Phoenicia, was the direct source of the symbol. BAR readers in turn took issue with Lubetski’s thesis.h (Lubetski also misread the inscription.13)

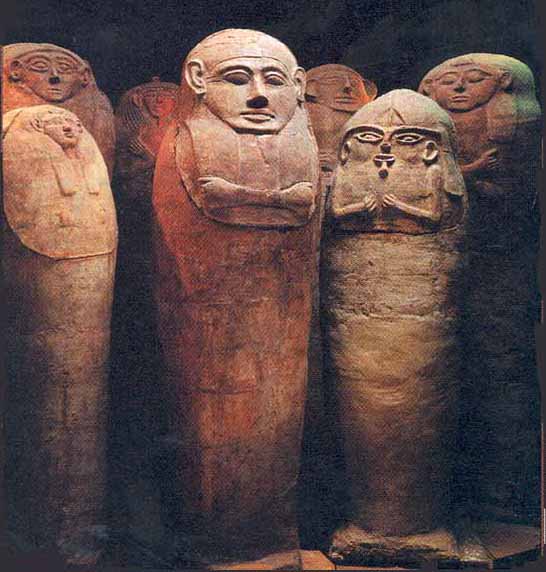

In my view, neither Cross nor Lubetski is quite correct, although Cross is closer to the truth. Egyptian influence is abundantly evident in Palestine throughout the Bronze Age (3000–1200 B.C.E.). For example, we find large quantities of Egyptian and Egyptianized pottery for as far back as the Early Bronze Age (3000–2200 B.C.E.) from Arad in the south to Megiddo in the north. Hieroglyphic inscriptions have been discovered in Arad, Megiddo, Beth-Shean and elsewhere. Egyptianized anthropoid coffins from the 13th century B.C.E. (Late Bronze Age) have been unearthed at Deir el-Balah in Gaza in the south and at Beth-Shean in the north. Rich Egyptian-style burial offerings have been found at numerous locations, from the southern site of Tel el-Far’ah to Lachish in central Judah and Beth-Shean in the north.14 In the Iron Age (1200–586 B.C.E.), faience artifacts, such as amulets depicting a variety of gods and goddesses from the Egyptian pantheon, are found at almost every ancient site in Israel. Egyptian iconography was also used in highly prized ivory carvings found at Samaria, capital of the northern kingdom of Israel (see artifacts in the sidebar “Egyptian Influence in Ancient Israel”).15

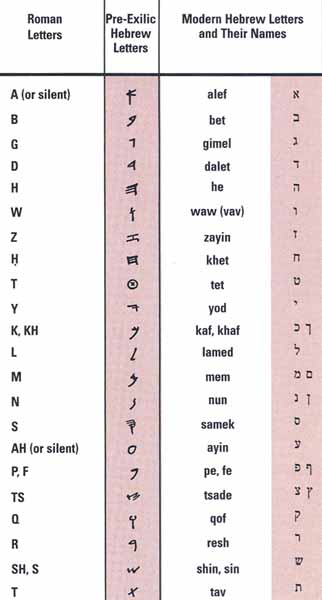

Even Hebrew writing can be traced indirectly to Egypt. Hebrew script is based on the script of the Phoenicians, who in turn borrowed extensively from the Proto-Canaanite and Proto-Sinaitic alphabets, which in fact developed from Egyptian hieroglyphs.

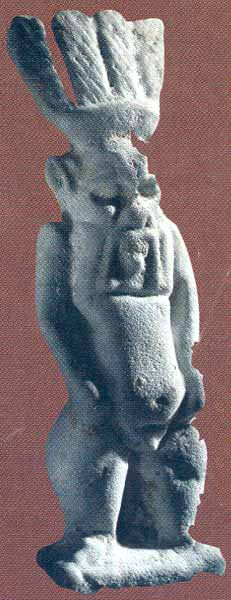

At the time the seals and corresponding bullae of Hezekiah were being produced, many other examples of Egyptian influence were present in Judah. Egyptian hieratic numbers are used on Hebrew dome-shaped weights and ostraca. The Egyptian ankh is widely used on seals. The Egyptian god Bes is frequently painted on storage jars, as at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, or appears as an amulet; later Bes is found on fourth-century B.C.E. Samarian coins. The Judahite Ashtoret or Asherah (a common pillar figurine) wears an Egyptian hairstyle. Sphinxes and griffins found in Israel wear crowns of Egypt’s upper and lower kingdoms. An oblong frame resembling that of an Egyptian cartouche (a sovereign’s name enclosed in an oval) appears on several seals and bullae—but unlike those in Egypt, it contains no royal name.

Winged sun disks, similar to those on our bullae, appear on three Israelite Hebrew seals of the eighth century B.C.E.16 This emblem is found even more often in Phoenician iconography. For example, the icon is on five Phoenician seals17 and two Phoenician/Punic gold pendants of the seventh to sixth century B.C.E., one found at Carthage, in Tunisia, and the other at Motya, in Sicily. These both have winged sun disks with six rays.18

Egypt probably exerted the strongest influence on Judahite iconography, but elements from other cultures—Canaanite, Mycenaean, Assyrian and Hittite—can be clearly discerned as well. Aramaic and Assyrian motifs are also common in both Judahite and Phoenician art.

Judah was hardly the only ancient culture to borrow iconography from its neighbors. Phoenician cities, including Tyre, Sidon and, especially, Byblos were awash in Egyptianized material culture. In like fashion, the royal emblems Hezekiah adopted—the winged scarab and the winged solar disk—were common in both Phoenician and Aramaic iconography.

The motifs adorning the emblems of high officials and royalty throughout the ancient Near East were drawn from a fund of symbols and images common to the whole region. Once a symbol had been associated with authority, rule, domination or power, it was appropriated by those who wished to embellish their public image.

I believe that this is what happened in Israel and Judah. Although winged sun disks and scarabs had originated in foreign lands, by the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E., when they appeared on Hebrew seals, they were already quite old and bereft of any religious significance. They were used solely for their decorative value and their connotation of power19—and should be regarded as Israelite/Judahite. When Hezekiah adopted the two-winged scarab and the two-winged sun disk with six rays as royal emblems, he was simply appropriating generally accepted icons of royal power and not importing meaning from either Phoenicia or Egypt.

We also learn much from the inscription on the bullae, “Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz, King of Israel.” The ubiquitous lamed (l), which means “belonging to,” regularly appears as a prefix to the name of the owner. The words “son of” are in brackets to indicate that the words are not actually there, but are understood. The omission of bn, or “son of,” is not a mistake. We know that it is an intentional omission because it is regularly left out of inscriptions even when there is sufficient space. Of 57 different seal impressions on storage jar handles from the time of King Hezekiah, only two include the word bn; the rest omit it.20

The spellings of key words in these seals are quite interesting because they tell us something about the development of the language. Hebrew is written without vowels. In the tenth century C.E., scribes developed a system of “pointings,” subscripts and superscripts that were placed under and over letters to indicate vowels. These are still used in Hebrew prayerbooks in the United States and elsewhere, but not in modern Hebrew newspapers and books in Israel. Nevertheless, at an earlier stage in the evolution of Hebrew orthography (spelling), a few consonants were also given vowel values (he, or h, served as a and waw, or w, served as o or oo). When used as vowels, these letters are called matres lectionis, mothers of reading. When these vowels are included in ancient inscriptions the spelling is said to be plene, full. When they are omitted, the spelling is said to be defectiva, defective.

On the bullae we have been considering, Judah is written in defectiva spelling: yhdh, Yehudah. The plene spelling would insert the vowel in the middle: yhwdh. The pronunciation is the same, but the oo vowel in the middle is more clearly indicated by the letter waw. The name Yehudah is recorded more than 800 times in the Bible, always appearing in its plene spelling, yhwdh

That the spelling on our bullae is defectiva has chronological significance: We do not see the plene spelling of Judah consistently used in inscriptions until 200 years after Hezekiah’s reign. Either the Biblical texts were written down at least two centuries after Hezekiah or the texts we have were later spelling-corrected.

On the bullae, Hezekiah’s name is spelled h

There is no clear explanation for these variant spellings. Perhaps it shows the chronological evolution of the language, with the texts containing the defectiva spellings being earlier. But the fact that all the bullae spell Hezekiah’s name the same way, despite the availability of other spellings, may indicate that all three of the seals impressed in these nine Hezekiah bullae were made in the same workshop.

The source of these bullae raises another big question. All of the bullae hoards that have been recently brought to light came from the antiquities market; not one was found in a scientific archaeological excavation, with one important exception not relevant to this discussion.i It is reasonable to ask whether they could be fakes. The universal answer of all experts in the field is “no.” It is simply impossible to fake them. The wet clay bullae were not baked at the time they were imprinted, but dried upon the documents they sealed. They hardened only in a fire that destroyed the documents the bullae sealed. For this reason they are very fragile—and have worn during the last 2,700 years. All have small cracks and surface corrosion, and under a microscope we see small crystals in the cracks and on damaged edges and surfaces. None of this can be duplicated.21

The bullae that are discussed for the first time here seem to be part of a larger group that came onto the antiquities market in Jerusalem in 2001 and were purchased by several individual collectors. One major collection of 109 bullae that has stayed intact, known as the Moussaieff Collection (after Shlomo Moussaieff, who authorized me to publish them in 1997 (in Hebrew; an English version appeared in 1999)22, surfaced in the mid-1990s. The new hoard contains many duplicates of bullae in the Moussaieff Collection. These duplicates suggest that both collections were once part of an even larger group.

A closer look reveals that the duplicates in the new group are more complete or better preserved than those in the Moussaieff Collection. I can only conclude that the group that once included both the new hoard that came to light in 2001 and the Mousaieff Collection was divided into two groups, one containing the more complete and better preserved bullae and the other the less complete and the less well-preserved pieces. The latter group was acquired by Moussaieff. The better pieces were withheld until 2001.

We will never know for certain where they came from, however.j Nahman Avigad assumed that the hoard he published in 1986, which may also be part of the large group, were found in the vicinity of Tel Beit Mirsim in southern Judah.23 Frank Cross thought it likely that they came from an archive in Jerusalem.k

My guess is that they came from a site known as Khirbet el-Qom, near Hebron, because of a bulla in the Moussaieff Collection that bears the inscription “Epai son of Natanyahu.” Epai is an extremely rare name—but it appears on an unpublished bulla in the new hoard,24 further indicating that the two hoards were originally one. Although the names are the same, the seals are quite different; apparently this Epai also had at least two seals. The name also appears twice in a late eighth or early seventh century B.C.E. burial inscription from Khirbet el-Qom,25 along with the father’s name, Natanyahu. I suspect that this was the same Epai, son of Natanyahu, whose seals are impressed in the bullae we now have. If that is so, the bullae may well have been produced in Khirbet el-Qom, where Epai, son of Natanyahu, was buried.

Incidentally, the very same name shows up in, of all places, a recently published graffito on a stone block acquired on the Jerusalem antiquities market.26 This is a soft limestone that is very similar to others that came from Khirbet el-Qom—and the graffito bears a close paleographical resemblance to other writing from there. It very likely came from the same place, and it makes us wonder: Who was this Epai, son of Netanyahu? He must have been one important—or ubiquitous—person. Perhaps future finds will enlighten us. The story of archaeology never ends.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “Jeremiah’s Scribe and Confidant Speaks from a Hoard of Clay Bullae,” BAR 13:05.

See Frank Moore Cross, “Nahman Avigad: In Memoriam,” BAR 18:03, and “Nahman Avigad, 1905–1992,” BAR 18:03.

See, for example, Philip J. King, “The Great Eighth Century,” BR 05:04; Joanne Hackett, Frank Moore Cross, P. Kyle McCarter, Ada Yardeni, André Lemaire, Esther Eshel and Avi Hurvitz, “The Siloam Inscription Ain’t Hasmonean,” BAR 23:02.

See Frank Moore Cross, “King Hezekiah’s Seal Bears Phoenician Imagery,” BAR 25:02.

See Robert Deutsch, “First Impression: What We Learn from King Ahaz’s Seal,” BAR 24:03.

Cross, “King Hezekiah’s Seal Bears Phoenician Imagery,” BAR 25:02.

See Meir Lubetski, “King Hezekiah’s Seal Revisited,” BAR 27:04.

Deryck Sheriffs, “Decoding Judahite Symbolism,” Paul S. Forbs, “Wrong on Several Counts” and Gabe Moskovitz, “Hezekiah’s Agenda,” Queries & Comments, BAR 27:06.

That hoard was found at the City of David excavations that were led by the late Yigal Shiloh. See Tsvi Schneider, “Six Biblical Signatures,” BAR 17:04.

See Hershel Shanks, “Bringing Collectors (and Their Collections) Out of Hiding,” BAR 25:03.

Cross, “King Hezekiah’s Seal Bears Phoenician Imagery,” BAR 25:02.

Endnotes

Robert Deutsch, Messages from the Past (in Hebrew) (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications, 1997), p. 35. See also the English translation (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications, 1999), p. 42.

For those who want exact figures, it is 13.2 mm (0.52 inch) in width, 11.9 mm (0.47 inch) in height and 1.8–3.8 mm (0.07–0.15 inch) thick. The seal impression itself is very small, 11.4 mm x 9.8 mm (0.45 x 0.03 inch). On the back is the imprint of the papyrus document, and holes and grooves mark where the cord that tied the document ran.

David Ussishkin, “The Destruction of Lachish by Sennacherib and the Dating of the Royal Judean Storage Jars,” Tel Aviv 4 (1977), pp. 28–60.

Lubetski argued that because “Judah” was at the top of the seal, the inscription should read, “Judah/Belonging to Hezekiah, son of Ahaz, King” instead of “Belonging to Hezekiah, son of Ahaz, King of Judah.” On the basis of this distorted reading, Lubetski claimed that Judah belonged to Hezekiah, affirming his position as ruler. Lubetski admits that we are not accustomed to the “novel ending ‘king’ on seal impressions” from Israel. Indeed! As the bullae discussed in this article demonstrate, the phrase is always “King of Judah.” Of course not all of these were available to Lubetski when he wrote his article. But the bulla of Ahaz certainly was (see Robert Deutsch, “First Impression: What We Learn from King Ahaz’s Seal,” BAR 24:03). The formula of Ahaz’s inscription is exactly the same as we now see on these Hezekiah bullae. In Ahaz’s bulla, the inscription is in three lines and reads from top right to bottom left: “Ahaz, [son of] Yehotam, King of Judah.” Lubetski’s silence regarding the formula on the Ahaz’s bulla is enigmatic (or perhaps he deliberately ignores it, as it doesn’t fit his theory). This silence is also observed by Lubetski’s critic, Edward Greenstein, in “Follow the Formula,” Queries & Comments, BAR 28:02. The same reading—that Hezekiah was “King of Judah”—is clear from the newly revealed Hezekiah bullae presented here.

Trude Dothan, The Philistines and Their Material Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), pp. 252–288, especially 256, 277, 278.

Richard David Barnett, Ancient Ivories in the Middle East, (Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University, 1982), p. 49, plates 48–49.

Nahman Avigad, revised and completed by Benjamin Sass, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Israel Exploration Society, Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1997), no. 3; Robert Deutsch and André Lemaire, Biblical Period Personal Seals in the Shlomo Moussaieff Collection, (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications, 2000), nos. 13 and 14.

Georgio Pisano, “Jewellery,” in Sabatino Moscati, ed. The Phoenicians 1988, pp. 376–377, 626, 654, nos. 250 and 416. For a detailed discussion on the winged sun disk motif, see Dominique Parayre, “A propos des sceaux ouestsémitiques: le role de l’iconographie dans l’attributation d’un sceau à une aire culturelle ou à un atelier,” in Benjamin Sass and Christoph Uehlinger, eds. Studies in the Iconography of Northwest Semitic Inscribed Seals (Fribourg, Switzerland: University Press; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1992), pp. 27–51.

Frank Moore Cross’s assumption that the “scarab and the sun-disk imparts a religious significance” in Judah, as also Meir Lubetski’s assumption that the “Judean king gazed aloft to the God in heaven for deliverance,” are mere speculations.

Andrew G. Vaughn, Theology, History, and Archaeology in the Chronicler’s Account of Hezekiah (Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press, 1999), pp. 199–216, XXIIe and XXIIIa.

Deutsch, Messages from the Past (in Hebrew) (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications, 1997).

Nahman Avigad, Hebrew Bullae from the Time of Jeremiah: Remnants of a Burnt Archive, (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1986).

Now in the collection of J. Chaim Kaufman and to be published by me in a forthcoming volume on the J. Chaim Kaufman collection.

William G. Dever, “Iron Age Epigraphic Material from the Area of Khirbet el-Qom,” Hebrew Union College Annual 40/41 (1969–1970), pp. 169–170.