When the National Rifle Association recently elected Charlton Heston, who is best known for his portrayal of Moses in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, as its new president, the NRA’s vice president said that it was “a way of saying, ‘Hey, Moses is on our side.’” And when Jeffrey Katzenberg, cofounder of the DreamWorks studio, wanted to show that his animation team could compete with Disney, he produced The Prince of Egypt, the first major film about Moses in more than 40 years.

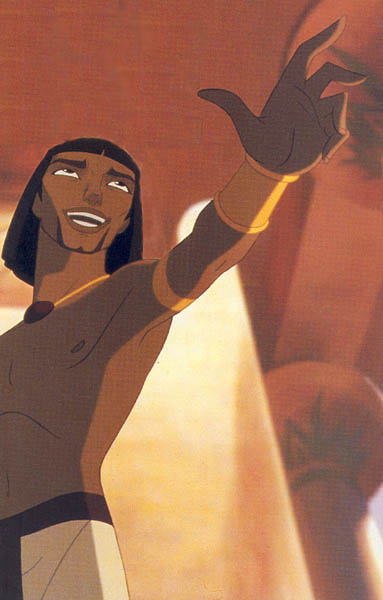

The Prince of Egypt, which premiered to great fanfare just before Christmas, features probably the best and most seamless integration of computer-generated images and hand-drawn animation to date, and may represent a step forward for mature storytelling in animated films. There are no cute and cuddly sidekicks, and there are no talking animals or gargoyles (as in Disney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame). The central relationship is not between two dreamy lovers but between two brothers who are torn apart by their respective destinies. The songs, sung by some of today’s top-selling pop performers, speed the narrative along while highlighting the emotional and thematic significance of key plot developments, such as the execution of the Hebrew male children, Moses’ spiritual growth during his years living with his father-in-law, Jethro, and the contest of wills between Ramesses and Moses.

In this version of the story, Moses (the voice of Val Kilmer) and Ramesses (Ralph Fiennes) are not jealous rivals for the throne but siblings who feel a genuine brotherly bond. Ramesses, the elder, is assured of his place on the throne, but he feels he cannot live up to the standards that have been set for him by his father, Seti (Patrick Stewart). Moses, the younger brother, is a wild and reckless fellow who keeps getting his older brother into trouble. The film begins with the two of them engaged in a chariot race, a chaotic chase in which they knock the nose off a sphinx, among other things.

One night, as Moses runs out into the street in pursuit of a Midianite woman who has escaped from her captors in the palace, he bumps into the Hebrew slaves Aaron (Jeff Goldblum) and Miriam (Sandra Bullock). Miriam tells Moses that he is really a Hebrew like them and that his mother set him adrift in a basket years ago to save him from a massacre. Their story is confirmed when Moses finds a wall of hieroglyphs commemorating the slaughter. In a creative sequence, the hieroglyphs come to life in a nightmare and reenact the story of Moses’ infancy. Seti, unaware that Moses is one of the Hebrew boys who would have been killed by his decree, tries to explain it away: “Sometimes, for the greater good, sacrifices must be made.” Moses cannot accept this, and when he tries to stop an Egyptian taskmaster from beating a Hebrew slave, he accidentally knocks the taskmaster off the scaffolding and to his death. Moses, fearful and ashamed, runs out into the desert, leaving Ramesses behind.

Moses meets Jethro (Danny Glover), marries his daughter Zipporah (Michelle Pfeiffer)—who, of course, turns out to be the Midianite girl he was pursuing earlier—and becomes a shepherd like them. One day, he sees a strange glow in the distance and discovers a burning bush. This scene is particularly clever: To demonstrate that the flames burn but do not consume, the animators have Moses put his stick in the flames, and then his hand, both of which come out unscathed. Then, as the voice of God tells Moses to lead his people into a land flowing with milk and honey, the bush quietly grows green leaves, a promise of the life and prosperity that is to come.

Moses returns to Egypt expecting to confront Seti, but he discovers that Ramesses has succeeded to the throne. Ramesses is the film’s most tragic figure, and he almost steals the show from Moses. The young Ramesses was torn between his love for Moses and his need for his father’s approval. When Moses returns, Ramesses is initially happy, but he is bemused and distraught when Moses tells him to let the Israelites go. Ramesses cites tradition and says he cannot disappoint the memory of his father. As the plagues escalate, and their toll on the Egyptians increases, Ramesses’ heart hardens until, standing before the hieroglyphs that commemorate the slaughter of the Hebrew children, he says it is time to finish Seti’s job. Moses is aghast: “Ramesses, you bring this upon yourself,” he warns. Before Ramesses can fulfill his threat, however, the plague that kills the Egyptian firstborn, including Ramesses’ own son, strikes. Moses pays Ramesses one last visit after that and Ramesses says the Hebrews may go. Then Moses, heartbroken by the damage that has been inflicted upon his former home, steps outside, where he breaks down and cries against a wall.

The Prince of Egypt, like other Moses films before it, weaves fine entertainment and compelling human drama from the threads of the biblical narrative. It also touches on contemporary social issues, such as the question of masculinity and the transmission of political and racial beliefs from father to son. Ramesses does not appear to be wholly to blame for his actions; rather, he gives in to the policies of his tyrannical father. Moses, on the other hand, turns his back on Seti once he learns of his adoptive father’s murderous inclinations and finds inspiration in a surrogate father, Jethro, who points his attentions heavenward to an even more benevolent parent.1

The Prince of Egypt had its genesis in a conversation between director Steven Spielberg, movie executive Jeffrey Katzenberg and music producer David Geffen shortly before they founded the DreamWorks studio. As they were discussing possible subjects for an animated feature film, Spielberg, who had already paid homage to DeMille’s epic with Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and, indirectly, with Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), turned to Katzenberg and said, “Why don’t you do The Ten Commandments?” Spielberg and Katzenberg were not as interested in telling the Bible story as they were in re-creating a memorable event in the history of popular culture.

That event, the release of DeMille’s 1956 epic, made such a strong impression that no one since has attempted a theatrical film on that subject and on that scale. DeMille’s film was itself a remake of an almost equally impressive film that he had directed during the silent era. Anyone who has produced a feature film about Moses in the past 75 years has had to deal in some way with DeMille’s near monopoly of the story of the Exodus.

DeMille’s weighty legacy helps explain why there are far fewer films about Moses than there are about Jesus.a Moses would seem to be a safer character: He appeals to Jews and Christians alike; the story of a Hebrew slave raised as an Egyptian prince is full of possibilities for character development; and no one has ever claimed divine status for Moses, who was a fully human individual capable of losing his temper (he killed at least one man with his own hands). But the story of Moses, a man who led an entire nation out of bondage, must be told on a grand scale, unlike the story of Jesus, which takes place mostly in small villages and can be filmed relatively inexpensively. Few though they may be, films about Moses reflect an interesting range of responses to modern questions concerning political ideals, interfaith relationships, the juxtaposition of science and religion, and the need for a moral code to govern human behavior.

The first film about Moses was made in France. The Pathé studio released Moses et l’Exode de l’Egypte in 1907. Confetti stood in for manna falling from heaven, streamers for flames, and God wore a paper halo. The film was 478 feet long and, at typical silent-era projection speeds, would have lasted between five and ten minutes.2 Other French studios followed suit with Israel in Egypt (1910) and The Infancy of Moses (1911).3

In America, the Vitagraph company released a five-part series of films under the collective title The Life of Moses between December 1909 and February 1910. Directed by J. Stuart Blackton, each film took up a single reel and told a different episode, such as the Red Sea or the giving of the Ten Commandments.4 But Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 Ten Commandments was the first truly remarkable film on the subject.

DeMille was the son of a successful playwright and had once considered joining the clergy but decided against it when he realized that Broadway melodramas, with their nondenominational tales of the conflict between good and evil, had the potential to reach more people than any sermon ever could. In 1913, he was hired to direct films that would bring respectability to the cinema and attract a higher class of customer than those who were flocking to see slapstick comedies.5 DeMille accomplished this, in part, by hiring stage actors, and even opera stars, to appear in his silent films, many of which were based on popular novels or on historical characters such as Joan of Arc. After the First World War, DeMille made high-society dramas, but they were ridiculed as kitschy. The Ten Commandments revived his career and defined the shape it would take thereafter.

The film was not about the life of Moses, per se. Like other films of the late silent period, it had two parts: a biblical story extravaganza, and a modern morality tale. DeMille’s film critiqued modernity and the tendency of modern people to scorn the moral lessons of the past; it also critiqued the religious fundamentalism that had arisen in response to modernity. Fundamentalism ensured that biblical stories were as familiar to working-class audiences as they were to the upper classes, so DeMille’s intertitles frequently specified the verses they quoted or drew upon for their inspiration. And, since all things Egyptian were popular at the time, thanks to Howard Carter’s discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, the statues and monuments constructed by the Hebrew slaves in the film were based on archaeological discoveries, lending an air of authenticity to DeMille’s film.

DeMille made his critique of modernity plain from the film’s outset. Its opening titles read:

Our modern world defined God as a “religious complex” and laughed at the Ten Commandments as OLD FASHIONED.

Then, through the laughter, came the shattering thunder of the World War.

And now a blood-drenched, bitter world—no longer laughing—cries for a way out.

There is but one way out. It existed before it was engraven upon Tablets of Stone. It will exist when stone has crumbled. The Ten Commandments are not rules to obey as a personal favor to God. They are the fundamental principles without which mankind cannot live together.

They are not laws—they are the LAW.

The film then proceeds to sketch out the basics of the Exodus story, beginning with the slaves pulling a giant sphinx and continuing through the death of the firstborn, the Exodus and the parting of the Red Sea to the giving of the Ten Commandments. God, his words appearing like flame out of a string of fireballs, dictates the commandments to Moses, who chisels them into the rock; meanwhile, at the foot of the mountain, the Hebrews are engaged in an orgy. Miriam (Estelle Taylor) strips and dances before the golden calf, declaring to her countrymen, “Come worship ye the golden god of pleasure! For the god of Israel heareth not—neither doth he see!” She is immediately struck with leprosy, and when Moses comes down and confronts the Israelites, lightning follows, destroying the golden calf and the revelers alike. The sequence, mixing episodes from Exodus and Numbers with fictitious elements, catches DeMille at his most lurid and extravagant.

The film then dissolves to an image of a middle-aged woman (Edythe Chapman) reading the story to her two grown-up sons. One of them, a business contractor named Dan (Rod La Rocque), is clearly bored and declares, “All that’s the bunk, Mother! The Ten Commandments were all right for a lot of dead ones—but that sort of stuff was buried with Queen Victoria!” His brother, a simple carpenter named John (Richard Dix), holds the Decalogue in higher esteem: “Laugh at the Ten Commandments all you want, Danny—but they pack an awful wallop!” The second half of the film shows how Dan, who vows to break all ten of the commandments, is done in by his own immorality. He dilutes the cement in a church he has been hired to build, and the weakened wall collapses on his mother and kills her. He and the building inspector he has bribed get caught in a corruption scandal. He smuggles in jute, a fiber used mainly for burlap and twine, as filler for his plaster, but the boat carrying the jute picks up Sally Lung (Nita Naldi), a French-Chinese refugee from a leper colony, who has an affair with Dan and spreads her leprosy to him and his wife, Mary (Leatrice Joy). Dan ultimately kills Sally, who collapses before a statue of the Buddha and taunts him: “Danny dear—I’ll tell the Devil, you won’t be far behind!” Dan tries to escape in a motorboat named Defiance, but a storm sends him crashing into a cliff, where he dies.

Although the biblical prologue made up less than half of DeMille’s film, the images were so powerful that it remained the definitive treatment of Moses in the movies for years.

The financial constraints of the Great Depression, and the practical restraints imposed by early sound-recording equipment caused the religious spectacular to all but vanish during the 1930s, except for reissues of older films with music and sound-effects tracks.

All that changed once the Second World War ended and the cinema found itself competing against television. Audiences needed a reason to leave their homes, so movie studios began to promise bigger screens, bigger sounds, and splashier sets, costumes and effects than anything that could be found on TV. America found itself wielding international power to an unprecedented degree, and the epic genre, with its images of construction and destruction on a massive scale, flaunted the affluence of an economically invigorated society. For the less pious members of the audience, biblical epics offered the potential for miraculous special effects and action-packed battle scenes as well as half-naked men and women, whose state of undress was justified by the ancient setting and the moral message of the films.6

DeMille himself revived the biblical epic genre genre in 1949 with Samson and Delilah, a lurid yet reverent box-office smash, whose $9 million gross was soon eclipsed by the $11 million earned by Henry King’s David and Bathsheba (1951), the $17 million earned by Henry Koster’s The Robe (1953) and the $34 million earned by DeMille’s own remake of The Ten Commandments in 1956.7

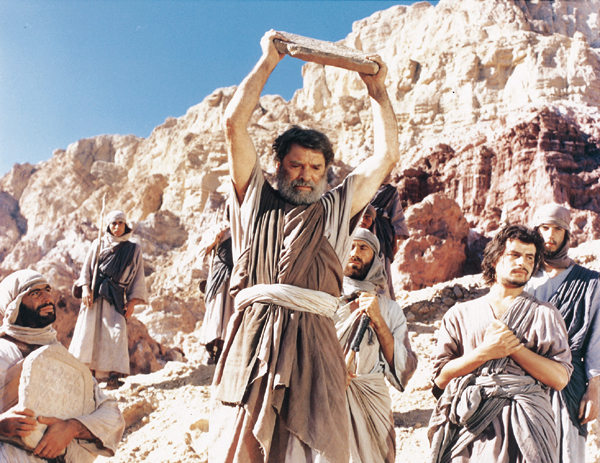

His remake was not divided into an ancient story and a modern story, as the original had been in 1923. Instead, he explored modern political themes within the ancient story, using biblical events as pegs from which to hang a largely fictitious tale. As before, he relied on artists and on archaeological discoveries to attract audiences and to boost the superficial credibility of his film. In a trailer advertising the film, DeMille pointed out that Charlton Heston’s profile resembled that of Michelangelo’s statue of Moses.8 He also cited the Dead Sea Scrolls, which had been discovered just a few years before, to back up his claim that Philo and Josephus, two of the historians upon whose works the script was allegedly based, had had access to similar ancient sources that still awaited discovery. DeMille also shot much of the film in Egypt, so that audiences could, as the film’s opening credits put it, “make a pilgrimage over the very ground that Moses trod more than 3,000 years ago” for the price of a mere movie ticket.

DeMille believed passionately in this project, which proved to be his last as a director. He suffered a heart attack while preparing to shoot the Exodus but was back on the set after a day’s rest.9 When the film was finished, he made free prints available to prisons and even offered to distribute it in the Soviet Union, provided that the censors not touch it.10

This last proposal was especially cheeky, considering the explicitly anti-Communist tone of the opening prologue, which DeMille himself delivers to the audience from behind a microphone. The underlying theme of the film, he says, is “whether men are to be ruled by God’s law or whether they are to be ruled by the whims of a dictator like Ramesses. Are men the property of the state? Or are they free souls under God? This same battle continues throughout the world today.”

In keeping with this theme, DeMille turned the ancient Israelites into proto-Americans. No mention is made of the fact that the Israelites, as well as the Egyptians, owned slaves. No mention is made of the purity laws and religious rituals that set the Israelites apart as a unique ethnic and religious group. No mention is made of the impending conquest of the promised land, in which whole Canaanite towns and villages would be destroyed. Instead, God compels the Israelites to spread a concept of liberty that bears more than a passing resemblance to American political ideals. Some scholars have suggested that Moses, in the final shot, raises his hand in a pose that is intended to resemble the Statue of Liberty.11 The last words of dialogue in the film, spoken by Moses, are taken from Leviticus 25:10, but with one subtle revision. Moses gives his benediction, saying, “Go, proclaim liberty throughout all the lands, unto all the inhabitants thereof.” The verse, which is also engraved on the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, refers to the Jubilee Year, when debts are forgiven and slaves set free,b and speaks of a singular “land”; DeMille has Moses look forward to the spread of western democracy.12

DeMille also integrated elements from several religions to promote cooperation among the faiths. The overt Christianity of the 1923 film is absent altogether, though Christ motifs are tucked into the film at key points. For example, Pharaoh orders the death of all newborn boys in Goshen, not because he is afraid of Hebrew population growth, but because a star has prophesied the birth of a deliverer in their ranks.13 This detail calls to mind Matthew’s version of the Nativity story, in which a special star signifies the birth of Jesus, provoking Herod to kill the infants in Bethlehem. Later, when the grown-up Moses meets his Hebrew mother, her beatitude echoes the Magnificat of the Virgin Mary: “Blessed am I among all mothers in the land, for my eyes have beheld the deliverer.” In another scene, Moses comforts a dying old man who says he once prayed “that before death closed my eyes, I might behold the deliverer who will lead all men to freedom.” (The old man doesn’t realize that his prayer has just come true, but the audience does, of course.) The old man is reminiscent of Simeon, the righteous man in Luke’s Gospel, who recognizes the infant Jesus and prophesies that the young Christ will one day bring salvation to the gentiles and thus to the whole world.

The ancient biblical epic, as a genre, faded away in the 1960s, as production costs rose and audiences lost interest. But the genre found a revival of sorts on television, where feature-length films and miniseries based on the lives of Jacob, Joseph, David and Jesus played to relatively high ratings in the 1970s. These films had a more naturalistic feel than the epics of old. They eschewed the fancy costumes, splashy colors and picture-perfect landscapes of past epics in favor of authenticity. They were typically shot on location in the rugged countryside of Israel or some other country close to the Holy Land, such as Egypt or Tunisia.

Moses, the Lawgiver, which was broadcast on CBS in 1975, is only partly concerned with the Exodus. The second half of the film recounts the 40 years in the wilderness that followed, and it highlights the zeal, even the fanaticism, with which some ancient Israelites observed the Law. It is also unclear at times whether Moses (Burt Lancaster) is speaking for God or invoking God’s name in order to validate his own improvisations. After crossing the Red Sea, Moses tells the Israelites that they will be punished if they do not keep the Sabbath holy. When someone asks what the punishment will be, Moses replies, “We’ll think of that later. It’s enough to speak now of the Lord’s displeasure.” Here, he suggests that the Law is, to some extent, the creation of human lawgivers and not the exclusive decree of God. Some years later, in an episode culled from Numbers 15:32–36, two men are caught gathering palm fronds to start a fire on the Sabbath, and Moses orders that they be stoned to death. The director, Gianfranco DeBosio, then shows the brutality of the stoning itself and makes a point of showing the children who witness the execution flinching and covering their eyes.

The film’s treatment of Moses’ brother, Aaron (Anthony Quayle), raises interesting questions about the role of religion and the forms it may take. In DeMille’s films, the golden calf is presented as a god of hedonistic pleasure, and Aaron is coerced into making the calf by brethren who rejected God. In Moses, the Lawgiver, Aaron creates the golden calf, not because the Hebrews have turned away from God, but because they do not yet comprehend God. “This image is not God,” he tells them. “The very idea is absurd. But it will remind you of God each day that you pass by it. Its head the sun, its forehead the moon, its limbs the four corners of the universe, so what you see is the image of our unity as a people, the unity of a people chosen by God himself.” However, despite this lesson in metaphors, the Hebrews begin to worship the image itself, indulging in drink and dance and, before long, even human sacrifice. When Moses comes down from the mountain, punishment does not come from the heavens, as per DeMille, but through mass executions, as per the Bible. The Hebrews who worshiped the golden calf are stoned, thrown off cliffs, buried in caves and forced to drink molten gold.

Today, television continues to be the medium through which biblical stories are most often explored.14 The life of Moses was portrayed in two episodes of the NBC series Greatest Heroes of the Bible (1978–79) and in an Emmy-winning episode of the British-Russian series Testament: The Bible in Animation (1996). It was also featured in Moses (1996), a two-part movie broadcast on TNT starring Ben Kingsley as Moses.

Moses is one of a series of films released on video under the collective title “The Bible Collection.”15 It emphasizes the flawed humanity of the biblical characters while maintaining the utmost reverence for God.

Of all the on-screen interpretations of the life of Moses, Ben Kingsley’s may be the most emotional. He laughs when the Red Sea parts, and he weeps when the Israelites are struck down by the Levites for worshiping the golden calf. Kingsley’s cry of deep and personal anguish is far removed from the towering, authoritarian righteousness of Charlton Heston’s Moses. The Ten Commandments are not introduced, as they are in DeMille’s films, by a fireball that talks, nor does Moses simply dictate them to the people, as he does in Moses, the Lawgiver. Instead, God visits Mt. Sinai in a trumpet blast and a windstorm that terrifies the Israelites but causes Moses to laugh with joy. Moses begins to recite the commandments, and he is soon joined by other Israelites who spontaneously recite them alongside him. The Law, as portrayed in this film, is not something to be feared, but something to be followed willingly; it is also purged of its more problematic elements, such as the harsh punishment meted out to those who would gather sticks on the Sabbath.

The film ends on an upbeat note that extols the virtues of love and faith but omits any reference to, say, the impending conquest of Canaan.16 Moses bids farewell to Joshua on Mt. Nebo, telling him that a nation must be built on love, not anger. Moses then ascends the mountain to pray, and the film concludes with aerial shots of a green and apparently unpopulated land just waiting to be possessed, and a narrator who declares that the Israelites “ended their wandering.”

The Prince of Egypt never gets to the promised land. Like the films of Cecil B. DeMille, it comes to a stop at Mt. Sinai, but unlike the films that came before it, it omits the golden calf and other incidents that might complicate the Israelites’ newfound freedom. The film reaches its true climax at the Red Sea, when the Egyptians’ hold over the Israelites is severed forever and the charioteers are crushed and drowned beneath the collapsing waves. Like many other feature-length cartoons, The Prince of Egypt depicts the yearning for freedom—freedom from taskmasters, freedom from evil stepmothers, freedom from being confined to a genie’s bottle—but does not explore the responsibilities that come with freedom and the limitations that prevent it from being abused.

The filmmakers obviously wanted to please followers of the major religions—they went to great lengths to consult scholars from across the theological spectrum—but they are not particularly interested in what those religions have to say about social and ethical behavior. In the closing credits, they make a point of quoting several passages from the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament and the Koran, but the film never spells out the Ten Commandments themselves. Instead, it promotes a sort of generalized pop spirituality: Hold on, have faith, just believe. If the film has a shortcoming, it is this: The producers of past Moses epics, on screens both big and small, used his story as an opportunity to promote a moral vision or to stir thoughts on questions concerning morality, the law and how one’s own religious tradition may be interpreted. The producers of The Prince of Egypt, on the other hand, seem to want nothing more than to put on a show, to build a monument to their artistic and technical prowess that will stand for years to come, like a pyramid or a sphinx. Well, at least they pay their workers.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Peter T. Chattaway, “Jesus in the Movies,” BR 14:01.

See Michael Hudson, “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land,” and the accompanying sidebar on the Liberty Bell in this issue.

Endnotes

DreamWorks originally tried to create a genderless voice for God with the help of computers, but in the end, the voice was provided by Val Kilmer.

Richard H. Campbell and Michael R. Pitts, The Bible on Film: A Checklist, 1897–1980 (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1981), p. 2; Derek Elly, The Epic Film: Myth and History (London: Routledge and Kegan, 1984), pp. 35, 188.

Sumiko Higashi, Cecil B. DeMille and American Culture: The Silent Era (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1994), p. 1.

See Bruce Babington and Peter William Evans, Biblical Epics: Sacred Narrative in the Hollywood Cinema (Oxford: Manchester Univ. Press, 1993), p. 7; Gerald E. Forshey, American Religious and Biblical Spectaculars (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1992), p. 46.

Babington and Evans, citing Michael Wood, America in the Movies, or ‘Santa Maria, It Had Slipped My Mind’ (New York, 1978), in Biblical Epics, p. 10.

One early scene, in which Moses presents the Ethiopian king to Pharaoh’s court as an ally rather than as a humiliated foe is open to a number of interpretations. Forshey (Spectaculars, p. 132) notes that Moses’ graciousness to Ethiopia parallels America’s graciousness to former enemies such as Germany and Japan. Babington and Evans (Biblical Epics, p. 55), however, suggest that the scene reflects American concerns over Soviet influence in the Third World.

This plot element was reportedly inspired by Josephus’ account of an Egyptian scribe who predicted the birth and future success of Moses (Antiquities of the Jews 2.205). However, Josephus does not mention a star.

There have been a few theatrical films too, but they remain obscure and difficult to find. These would include Wholly Moses (1980), a comedy starring Dudley Moore, and Moses und Aron (1975), a German adaptation of Arnold Schoenberg’s three-act opera, which was first performed in the 1950s (Campbell and Pitts, The Bible on Film, pp. 64–65).

Previous films in the series depicted the lives of the patriarchs; one, Joseph (1995), won an Emmy for outstanding miniseries. However, ratings on subsequent installments have slipped, and as of this writing, executive producer Lorenzo Minoli has not found a network for the episodes on Solomon, Jeremiah and Esther, though CBS has expressed interest in an as-yet-unproduced film on Jesus (John Dempsey, “‘Jesus’ Won’t Bless TNT,” Daily Variety, July 20, 1998).

The next film in the series was Samson and Delilah (1997). The series, which explored the Book of Genesis in warts-and-all detail, jumps from the period of Israel’s oppression under the Egyptians straight to the period of Israel’s oppression under the Philistines, omitting anything that would make the Israelites look like oppressors themselves.