052

Poor Wenamun! Stranded in a foreign city, his money stolen and letters of introduction misplaced, the Egyptian official throws himself upon the mercy of the local administration—an all-too-familiar tale of a traveler in distress. But Wenamun’s story dates to the end of the Late Bronze Age (c. 1075 B.C.), in the days before American Express.

Wenamun’s calamities are recorded on an 11th-century B.C. hieratic papyrus now housed in Moscow’s Pushkin Museum. Our ancient traveler is dispatched from the Egyptian court to purchase wood at Byblos, a port city on the coast of what is now Lebanon. While moored in the harbor off the coast of Dor (in northern Israel), Wenamun is robbed by a crew member who makes off with his silver and gold.

This is just the beginning of Wenamun’s misadventures on the high seas of yesteryear. Later, he is shipwrecked on the island of Cyprus as he tries to make his way back to Egypt. At this point, however, the papyrus breaks off. We don’t know whether he eventually reaches Egypt safely or remains stranded forever on Cyprus. (The tale’s first-person narrative may suggest that Wenamun did make it home to recount his epic struggles to a scribe.)

Until recently, we did not even know if the story took place at all, whether it was pure fiction or contained a kernel of truth. One of the felicities of Shelley Wachsmann’s latest book, Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant, is that it confirms some of the facts in this ancient Egyptian yarn—such as the existence of maritime trade between Egypt and Byblos throughout the second millennium B.C., especially involving the export of cedar (and other woods) from Lebanon to Egypt.

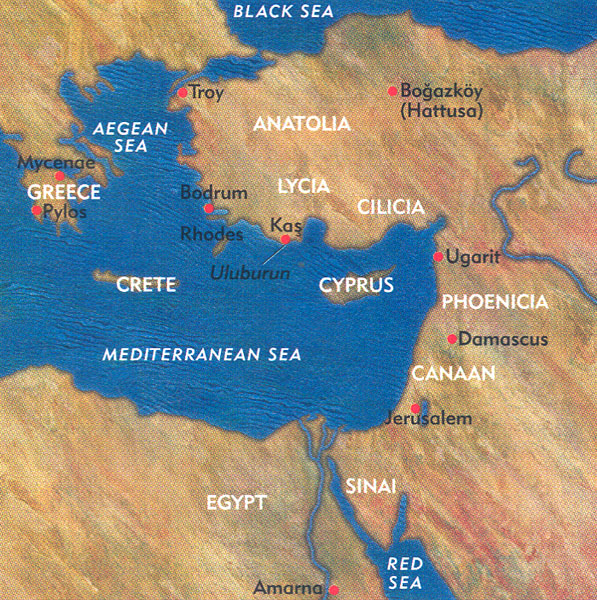

Wachsmann, best known perhaps for excavating and publishing the so-called “Jesus Boat” found in the Sea of Galilee, 053draws on a wide variety of evidence to produce this comprehensive study of seamanship in the Bronze Age (c. 3000–1000 B.C.) cultures of Canaan, Cyprus, Egypt and the Aegean.a Not only does he provide detailed discussions of ships and ship building—everything from anchors and hull construction to rigging and methods of propulsion—but he also addresses issues of trade, war and piracy, as well as the relevant texts from the archives of the great port cities of Ugarit in Syria and Pylos on the Greek mainland.

The stories of maritime adventures in the Bronze Age Mediterranean are full of drama, triumph and tragedy. Take, for example, the late 14th-century B.C. Uluburun shipwreck, off the southern coast of Turkey.b Excavated by George Bass, the “father of underwater archaeology,” and Cemal Pulak (both, like Wachsmann, now at the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A & M University), the wreck was discovered in 1982 by a young Turkish sponge diver, who reported seeing “metal biscuits with ears” on the seabed. The metal biscuits were in fact 60-pound ingots of pure copper, part of a cargo containing more than ten tons of copper and a ton of tin! That would have been enough metal to produce nearly 11 tons of bronze alloy—the metal of preference at that time (this was, after all, the Bronze Age).

The Uluburun shipwreck was the focus of 11 seasons of intensive underwater excavation from 1984 to 1994—no easy feat, given that the wreck lies under 140 to 170 feet of water, almost too deep for 054safe diving. Consequently, each archaeologist was allowed to dive to the wreck only twice a day, with each dive limited to about 20 minutes on the seafloor. Working at that depth induces a grogginess resembling the effect produced by a couple of martinis, according to Bass. Still, Pulak reports that over the course of the 11 seasons of excavation, the dedicated team of underwater archaeologists logged nearly 22,500 dives, spending more than 6,600 hours uncovering the buried wreck and its fabulous cargo.

The ship went down carrying not only a fortune in copper and tin but glass ingots, resin from the terebinth tree (a kind of sumac), ivory, ebony and cedar wood, and other raw materials. Among the other valuable items on board were gold and silver jewelry, pottery, weapons, tools and cylinder seals. In all, the wreck contained goods from at least seven different countries around the Mediterranean area. The excavations also turned up a nearly intact wooden writing tablet, known as a diptych, and parts of another. In ancient times, molten wax would have been poured into the hollow interior of this folding tablet, and a message would have been scratched into the surface of the wax once it had hardened. Unfortunately, the wax had long since dissolved in the seawater, so we will never know if the tablet once contained the ship’s itinerary, or its cargo manifest, or an official letter from one king to another, or

055

The problem is, we don’t know who sent the ship or why. Judging by its final resting place, the ship apparently departed from Cyprus or Syria and was heading somewhere in the Aegean, perhaps to the Greek mainland or Crete. Voyages during the Bronze Age usually followed a counter-clockwise route around the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean—for example, from Syria-Palestine and Cyprus west to mainland Greece, via the southern coast of Anatolia, Rhodes and the Cyclades; then returning southeast to Crete, directly south to Egypt, and back east again to the Levant. The Uluburun ship seems to have been following this circuit when it sank off the southern coast of Anatolia.

According to the excavators, the ship was trying to clear the rocky headland at Uluburun on its way to the Aegean when, possibly due to an unfortunate gust of wind, it slammed into the sheer rock face, spun around and sank with its cargo intact. No bodies were found, but the finds seem to indicate that the ship was of Canaanite origin, carrying passengers of several nationalities, including at least one Mycenaean.

The ship may have belonged to a wealthy, traveling merchant who sold goods around the Mediterranean and took advantage of the prevailing winds and currents. We know of at least one such ancient merchant, a man named Sinaranu who sent a ship from Ugarit to Crete in the middle of the 13th century B.C. In an appendix to Wachsmann’s book, J. Hoftijzer and W.H. van Soldt provide a text stating that Sinaranu’s imported goods are tax-exempt: “From this day on, Ammishtamru, son of Niqmepa, King of Ugarit, has exempted Sinaranu, son of Siginu; he is clear as the Sun is clear. Neither his grain, nor his beer, nor his oil will enter the palace (as tax). His ship is free (from claims). If his ship comes (back) from Crete, he will bring his present to the king and the herald will not come near his house.”

Although the excavation of the Uluburun shipwreck was concluded several years ago, the overwhelming mass of finds is only now beginning to be fully processed, studied and understood; it will be years before any firm conclusions can be reached.

Some 50 or more years prior to the disaster at Uluburun, the Egyptian pharaoh Amenophis III (c. 1391–1353 B.C.) may have sent an official embassy to the Aegean. The existence of such an embassy has been hotly debated over the past 20 years by a number of scholars. At the heart of the debate is the so-called Aegean List, names carved onto the base of a statue in the pharaoh’s mortuary temple at Kom el-Hetan, near the Valley of the Kings. This is a list of Aegean place names, including Crete (Keftiu), the Greek mainland (Tanaja), the cities of Knossos and Mycenae, the island of Kythera, and possibly the city of Troy. Nowhere else in Egypt do these names appear. They are unique to Amenophis III’s reign and to his mortuary temple.

Wachsmann suggests that the sites listed on this Egyptian statue appear to form a geographical itinerary of a sea journey around the Aegean. It is possible that the Aegean List provides a kind of manual for such a voyage—instructing Egyptian seafarers to proceed first to Crete, then to the Greek mainland via the island of Kythera, and then to return to Crete, presumably to replenish their food and water supplies, before completing the final leg of the journey back to Egypt.

056

But a number of scholars believe, and I agree, that the Aegean List records a specific journey to Greece and Crete authorized by Amenophis III, who is known more for his diplomacy than for his military campaigns (although he was not loath to use force when necessary). Six faience plaques, uncovered at Mycenae, bear the cartouche of Amenophis III. At no other site outside of Egypt have such plaques been found. Scarabs with the cartouche of Amenophis III or his wife Queen Tiy have also been found at sites around the Aegean, including Mycenae and Knossos—both of which, as we have seen, are mentioned on the Aegean List.

As part of his foreign policy, Amenophis III sent embassies to, signed peace treaties with, and married the daughters of the most powerful rulers of the day in Syria-Palestine, Anatolia and Mesopotamia. Some of these diplomatic missions are reported in the so-called Amarna Letters, an archive of cuneiform tablets discovered by a peasant woman in 1887 at Tell el-Amarna, halfway between Cairo and Luxor. We also know that Amenophis III, like other pharaohs, received gifts from foreign kings. One of the Amarna Letters, sent to Amenophis III from

057

Why would Amenophis III have sent embassies to the distant Aegean? Possibly because of the threat of another party—the Hittites in central Anatolia, far to the north. Under an ambitious king named Suppiluliuma, the Hittites, who had an on-again, off-again relationship with the Egyptians, were expanding their territory early in the 14th century B.C. By moving into northern Syria, the Hittites encroached upon territory that had been under Egyptian influence for more than a century. So Amenophis III befriended the various powers surrounding the Hittites—probably including the Mycenaeans, who exerted considerable influence along the Aegean coast of Anatolia. An embassy sent to the Aegean by Amenophis III would have been charged with hammering out peace treaties with Mycenaean powers, in order to stem Hittite expansion into western Turkey.

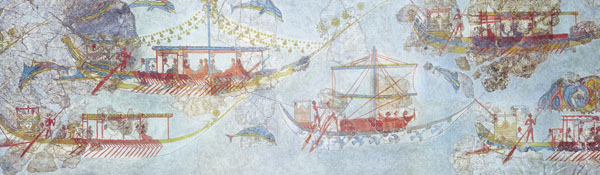

Just as the Mycenaeans made frequent sea journeys during the 14th and 13th centuries B.C.—to the western coast of Anatolia, to Syria-Palestine, to Cyprus and to Egypt—centuries earlier the Minoans from Crete had ventured to these very same areas. Sarah Morris of UCLA has suggested that a famous painted scene from the Aegean island of Santorini (ancient Thera) may depict a Minoan voyage to western Anatolia in the 17th or 16th century B.C. The paintings appear on the walls of a house in the town of Akrotiri. Around 1638 B.C., a violent volcanic eruption destroyed much of the island and dumped about 30 feet of ash and debris on what remained. Akrotiri was devastated, but the wall paintings were preserved.

The painting, dubbed the Miniature Frieze, depicts a variety of maritime scenes and runs around three walls of one room. Depicted on the south wall is a flotilla of vessels leaving one port city and arriving at another—a journey from the Aegean to Anatolia, Morris suggests, or from the Aegean to Libya, according to other scholars. Still others, including Wachsmann, argue that the voyage is strictly an Aegean one, perhaps part of an annual ceremony.

On the north wall of the same room is another puzzling scene, depicting three naked sailors floating in the water, either sideways or upside-down. These dead (or dying) sailors, foundering amid a number of ships, may have been the unlucky victims of human sacrifice, according to Wachsmann’s elaborately documented argument. Earlier scholars have suggested that these sailors were simply casualties of a battle fought in the area; indeed, warriors are shown marching on a nearby hillside. Curiously, as Wachsmann points out, neither the warriors nor the other people pictured in the scene appear to take notice of the floating corpses.

But who ran the ships depicted in the Miniature Frieze? Are they Theran, Minoan or something else? Scholars have long spoken about a Bronze Age “Minoan Thalassocracy” (from Greek words meaning ruling over the seas)—a theory that powerful Crete ruled over mainland Greece and the Cycladic islands for much of the second millennium B.C. The Minoans did exert considerable influence at this time, but they weren’t the only ones plying the waters of the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. There is a good deal of evidence indicating that Minoan vessels shared the seas with Egyptian, Canaanite and possibly Cypriot fleets; 061none of them held a monopoly or ruled over a true thalassocracy.

Minoans traveled extensively in the second millennium B.C., establishing colonies in the Cyclades and eastern Dodecanese, as well as on the western coast of Asia Minor. Minoan traders even ventured, perhaps, as far as Mari (in modern-day Syria), a powerful city in ancient Mesopotamia.

Cuneiform texts from the reign of Zimri-Lim, king of Mari around 1760 B.C., mention Minoan goods apparently transported from Crete to Mesopotamia—including daggers encrusted with gold and lapis lazuli, richly decorated vases, and various textiles and articles of clothing. According to one text, a pair of Minoan leather shoes was carried to the palace of the Babylonian king Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 B.C.), either by the Minoans themselves or by enterprising middlemen of other nationalities. Mysteriously, the shoes “were returned”—perhaps because they were thought unsuitable for a king. Hammurabi’s famous Code of Laws, which provides the earliest basis for the saying “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” does not mention any penalty for ill-fitting shoes!

Wachsmann is lucky in his subject. Sailing the wine-dark waters of the Bronze Age—is there more romantic material than that? His book is full of drawings of ships, maps and plans, and photos of various kinds. We learn how ships were built and rigged, what routes they traveled, what they carried. And the stories: mysterious shipwrecks, Minoan colonies in Canaan and Egypt, Sea Peoples. These things pass before Wachsmann’s attentive eye.

Poor Wenamun! Stranded in a foreign city, his money stolen and letters of introduction misplaced, the Egyptian official throws himself upon the mercy of the local administration—an all-too-familiar tale of a traveler in distress. But Wenamun’s story dates to the end of the Late Bronze Age (c. 1075 B.C.), in the days before American Express. Wenamun’s calamities are recorded on an 11th-century B.C. hieratic papyrus now housed in Moscow’s Pushkin Museum. Our ancient traveler is dispatched from the Egyptian court to purchase wood at Byblos, a port city on the coast of what is now Lebanon. While moored in […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Shelley Wachsmann, “The Galilee Boat—2,000-Year-Old Hull Recovered Intact,” BAR 14:05.

See the following articles in the September/October 1999 issue of Archaeology Odyssey: Cemal Pulak, “Shipwreck! Recovering 3,000-Year-Old Cargo,” and Dorit Symington, “Recovered! The World’s Oldest Book,” AO 02:04.