“Lost Gospels”—Lost No More

The New Testament, a 27-book collection of texts written within a century of Jesus’ crucifixion, is typically thought of as the one-stop source for all information about the origins of Christianity and for the answers to pressing moral and ethical questions. But these texts were not automatically declared scripture after their writers had put down their pens. It took some time, centuries in fact, for Christians to determine which texts were important enough and popular enough to be added to the Jewish Tanakh as a reflection of the “new covenant” ushered in by Jesus.

By the time that decision was reached, Christianity had gone through a period of intense literary activity, leaving the church with an embarrassment of riches from which to choose their sacred texts. The considerable literature that did not make the cut constitutes the Christian apocrypha.

The word “apocrypha” means “secret,” but by the end of the second century the term had taken on the pejorative meaning of “false” or “spurious.” Christians were urged to avoid reading these rejected texts because, as bishop Athanasius of Alexandria wrote (c. 367 C.E.), they “are used to deceive the simple-minded.” Once Athanasius and other church leaders decided on the official canon (meaning “standard” or “rule”) of Christian scripture, the rejected texts were apparently “lost” for centuries until the beginning of the Renaissance, when scholars journeyed to the East in search of old manuscripts gathering dust in monastery libraries, and more recently by archaeologists, who pulled tattered scraps of papyrus out of tombs and ancient garbage dumps.

Today scholars of the Christian apocrypha are challenging this view of the loss and rediscovery of apocryphal texts. It has become increasingly clear that the Christian apocrypha were composed and transmitted throughout Christian history, not just in antiquity. And they were valued not only by “heretics” who held views about Christ that differed from normative (or “orthodox”) Christianity, but also by writers within the church who did not hesitate to promote and even create apocryphal texts to serve their own interests.1

To some extent Christian apocrypha have been with us for as long as the texts of the New Testament. Ancient literature is difficult to date precisely, but arguments have been made, particularly by North American scholars, for dating some of the Christian apocrypha to the first century. Such is the case for several “lost” Jewish-Christian gospels—the Gospel of the Hebrews, the Gospel of the Nazareans and the Gospel of the Ebionites—known today only through quotations from these gospels made by early church writers such as Jerome and Origen. The Gospel of Thomas, a collection of sayings of Jesus, may have been assembled within a few decades of Jesus’ death.

Other early apocrypha are preserved in part within the New Testament. The gospel that scholars refer to simply as Q is a hypothetical document that consists of sayings of Jesus, some of which have been included in the canonical texts of both Matthew and Luke.a However, Q itself was not accepted for inclusion in the New Testament canon. We know it only from common quotations in Matthew and Luke.

Canonical texts hint of other written sources, such as the “Signs Source” in the Gospel of John and the “Passion Narrative” incorporated into the Gospel of Mark.

By the mid-second century, the four Gospels now included in the New Testament had become widely accepted as authoritative. But many Christians considered them incomplete accounts of the life of Jesus. Gaps left by the gospel writers were filled in with such texts as the Birth of Mary (sometimes referred to as the Protevangelium of James), containing details of Mary’s conception and birth, and the Childhood of Jesus (more commonly known as the Infancy Gospel of Thomas), featuring stories of Jesus performing miracles between the ages of 5 and 12. Both of these texts were extremely popular throughout the Middle Ages and can be found in numerous manuscripts dating from the fourth to the sixteenth centuries.

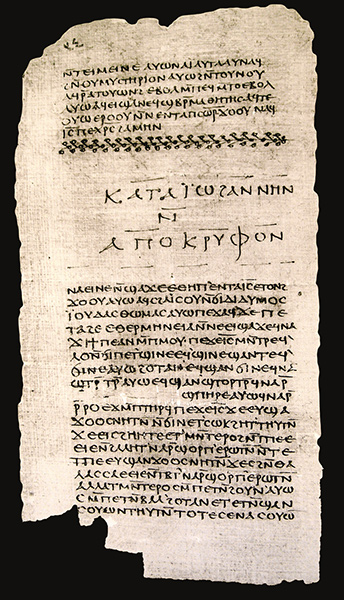

Other texts recount teachings of the adult Jesus, sometimes in the form of dialogue gospels—such as the Dialogue of the Savior and the Apocryphon of James—in which Jesus appears to the apostles after the resurrection and instructs them about the origins of humanity and how to achieve salvation. These particular texts did not share the popularity of the childhood gospels; indeed, scholars did not even know they existed until recently, when fourth-century copies of the texts were found in Egypt.

Internal disagreements led to division within Christianity, with various groups coalescing around charismatic teachers, such as Valentinus (100–160 C.E.) and Marcion (85–160 C.E.). Texts became arenas of conflict between the groups; their followers composed new gospels in which early Christian figures outside of the 12 apostles vied with the other apostles over points of Christian teaching and practice. The Gospel of Judas, for example, portrays Judas alone as the one who understood who Jesus was and condemns the 12 for leading others astray.b

The variety was vast and included more than just gospels. Each apostle was featured in his own book of “acts” documenting his missionary efforts. And additional apocalypses and letters were composed. Paul is said to have written a third letter to the Corinthians, and there is a correspondence between Paul and the first-century Roman philosopher Seneca. There is even a correspondence between Jesus and a Syrian king named Abgar.

All of these texts (and more) circulated in the first three centuries after Jesus’ crucifixion, some more widely than others, some achieving more esteem than others. But no formal decision could be made about which texts were to be considered authoritative for all Christians until after the emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313 C.E., allowing Christianity and other religions to be practiced freely throughout the empire. A consensus then emerged in the newly institutionalized church over which texts were to be included in their New Testament. The final shape of the canon was seemingly settled by 367 C.E. when Athanasius of Alexandria issued his annual letter for Easter. This 39th Festal Letter lists the 27 books of the New Testament as we have it today.2

It is often assumed that Athanasius’s letter had a devastating effect on the Christian apocrypha. Those who valued the rejected texts either hid them away or destroyed them for fear of excommunication, or worse, execution. Thereafter Christians of all nations focused their attentions entirely upon the texts of the canon.

According to this prevailing view, the Christian apocrypha were lost to history until Renaissance scholars, enamored with literature from Greek and Roman antiquity, traveled to eastern lands and returned with manuscripts of long-lost texts, which they could now disseminate widely thanks to the recent invention of the printing press.

The best-known of these travelers is Constantine Tischendorf, the German scholar who recovered the Codex Sinaiticus from St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt. Sinai.c Incidentally, Codex Sinaiticus includes two works that also did not become part of the New Testament canon: the Shepherd of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas. Manuscripts of other apocryphal texts were found at the monastery, and Tischendorf drew upon these manuscripts for his critical editions of Christian apocrypha, editions that remain influential to this day.

Scholars naturally prefer to work with manuscripts of the texts as close to their time of origin as possible. So you can imagine their delight in finding early manuscripts in archaeological excavations. In 1886–1887, a French archaeological team digging in a cemetery in Akhmîm in Upper Egypt excavated a portion of what appears to be the Gospel of Peter, which recounts the trial and crucifixion of Jesus using elements from the canonical gospels as well as some never-before-seen features, along with sections of the Apocalypse of Peter and the Jewish pseudepigraphon 1 Enoch.

This discovery was soon followed by excavations in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt. The Oxyrhynchus papyrus scraps included numerous Christian, Jewish and pagan texts.d Three pages were found from three separate copies of the Gospel of Thomas dating from the late second to the third century. The Thomas fragments were by far the most dramatic find at Oxyrhynchus, but this ancient garbage dump also yielded fragments of several other apocryphal texts: the Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Peter, the Acts of John, the Acts of Paul, the Acts of Peter and several unidentified gospel narratives.3

Apocryphal works have also come into scholarly hands via the antiquities market. In 1954 the Bodmer Library in Geneva began publication of a horde of manuscripts from the third to fifth centuries, apparently discovered by peasants near the Egyptian town of Dishnâ and sold through middlemen to several European and American libraries.4 Among the finds were a complete Greek copy of the Birth of Mary and portions of the Acts of Paul in Greek and Coptic.

Coptic is the language also of a number of other Egyptian discoveries originating, it would seem, from ancient Christian tombs.e These include the fifth-century Berlin Codex, containing a large portion of the Gospel of Mary, and the recently-published Tchacos Codex from c. 300, containing the one and only copy of the Gospel of Judas and several other texts.

The most famous discovery of Christian apocrypha is the Nag Hammadi Codices, a cache of over 50 texts discovered by Bedouin in 1945 in a mountainous area dotted with caves near the town of Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt.f The 13 codices contain 14 apocryphal texts, including a complete copy of the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip and the Gospel of the Egyptians, as well as dialogues, acts, letters and apocalypses.

The Nag Hammadi Library was a goldmine of apocryphal literature that, to some scholars, redrew the history of Christianity.5 It has become increasingly clear that Christianity began as a multitude of voices, each one declaring itself right and others wrong. One, led by the Roman Church, emerged as the victor. It was the Roman Church that determined the canon of the New Testament, effectively silencing contrary beliefs and casting itself as the true heir to the teachings of Jesus.

This revision of Christian history understood the Nag Hammadi Codices, and other manuscripts of apocrypha, as hidden away in order to safeguard them from confiscation by church officials looking to root out heresy. The Christian apocrypha were thus “lost” for over a thousand years. But scholars in the field are now challenging this narrative and demonstrating that the “lost gospels” were not so lost after all.6

First, the shape of the 27-book New Testament canon was not settled in the fourth century after all. The Bible took on different shapes in parts of the world outside of Roman influence. The Eastern Orthodox Church, centered originally in Constantinople, separated from Rome in the fifth century. Their New Testament did not include Revelation until the 10th century. Farther east, the Syrian Orthodox Church, established in 451 C.E., until recently read from a New Testament that lacked five of the 27 texts (those still debated in the fourth century: 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude and Revelation) and once included 3 Corinthians. So enamored was Syrian Christianity with apocryphal texts that monasteries throughout Turkey and Iraq have become a major source for manuscripts of Christian apocrypha.

Still farther east, the Bible of the Armenian Church included 3 Corinthians and the Martyrdom of John. And the Bible of the Ethiopian Church today includes not only additional Old Testament texts, including Enoch and Jubilees, but a New Testament canon with several texts related to church organization and practice along with the Book of the Covenant, the Book of the Rolls and others.

In sum, what constitutes the canon of the New Testament has varied over time and space. The line between canonical and non-canonical texts has often been blurry, and texts we believed “lost” were not lost to everyone.

Second, even after efforts to settle the New Testament canon in the fourth century, writers in the church continued to create entirely new apocryphal texts. After Constantine’s triumph, the once-outlawed religion now had to construct churches, inaugurate festivals and enshrine its heroes. From its beginnings, Christianity was a religion of texts, of story, and in this new environment they used story again for “inventing” Christianity.7 New apocryphal acts were written, such as the Acts of the Centurion Cornelius and the Acts of Titus,8 each telling the life of the saint using a combination of canonical and non-canonical traditions and ending with a story of the discovery and internment of the saint’s relics in his or her very own church.

The Coptic Church was particularly effective in composing such texts. A veritable cottage-industry of writings—known in scholarship as “pseudo-apostolic memoirs”—were created to institute feast days for early Christian saints.9

The Western Church worked at compiling and translating Greek texts for Latin readers, such as the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, which combines the birth of Mary with additional stories of the holy family in Egypt, and the Greek Acts of Pilate, which was repurposed and expanded as the Gospel of Nicodemus. Both Nicodemus and Pseudo-Matthew were widely copied in the West, and elements of their stories appear in art, literature and theater throughout the medieval period.

Not everyone in the churches valued the new texts, and certainly none of them was esteemed highly enough to become canonical, but they demonstrate that even after the formation of the canon, writers within the church were willing to create apocryphal texts—in effect, to create forgeries—when it suited their needs.

Third, if the churches were willing to write apocrypha and sometimes incorporate them in their liturgies, then it can hardly be true that they were vigorous in their efforts to suppress apocryphal texts, even particularly heretical texts. Recent re-evaluations of the story of the discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library suggest that the codices were not hidden in order to safeguard them from confiscation after all.10 The Bedouin who found the codices claimed to have discovered them in a large jar while digging for fertilizer, but there is good reason to believe they invented the story as a cover for grave robbery. Like the Akhmîm Codex, and the Berlin and Tchacos codices, the Nag Hammadi Codices were probably buried with the monks or collectors who valued them; likely they read (or heard) the standard texts of the Bible, just as everyone else, but saw something of value also in these non-canonical texts despite the occasional call for their destruction.

The canon of the New Testament has not been stagnant, as demonstrated by the Christian apocrypha. Whether a text is canonical or non-canonical has not always been clear, and the so-called “lost” texts were not lost to all. We are also aware that the modern interest in Christian apocrypha, occasioned in part by the attention paid to Dan Brown’s 2004 novel The Da Vinci Code, is far from new; Christians today read texts outside of the canon for the same reasons as their forebears: because the New Testament does not satisfy their needs for knowledge about the origins of Christianity nor for answers to all of their metaphysical and theological questions. The notion that “lost gospels” have been rediscovered makes for fascinating reading, but the history of the composition and transmission of the Christian apocrypha is far more complex than is usually told. Far from lost, these texts have always been with us and will be there whenever they are needed.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1.

See these articles regarding Q: Eta Linneman, “Is There a Gospel of Q?” Bible Review 11:04; Stephen J. Patterson, “Yes Virginia, There Is a Q,” Bible Review 11:05.

2.

Birger A. Pearson, “Judas Iscariot Among the Gnostics,” BAR 34:03.

3.

Stanley E. Porter, “Hero or Thief? Constantine Tischendorf Turns Two Hundred,” BAR 41:05; “Who Owns the Codex Sinaiticus?” BAR 41:05.

4.

Stephen J. Patterson, “The Oxyrhynchus Papyri,” BAR 37:02.

5.

Leo Depuydt, “Coptic: Egypt’s Christian Language,” BAR 41:06.

6.

Charles W. Hedrick, “Liberator of the Nag Hammadi Codices,” BAR 42:04.

Endnotes

1.

For an accessible collection of the early (first–fourth-century) texts discussed in this article, see Bart D. Ehrman, Lost Scriptures: Books That Did Not Make It into the New Testament (Oxford and New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2003). Late-antique and medieval apocrypha receive far less attention, but the forthcoming collection edited by Tony Burke and Brent Landau (New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans]) is a step toward remedying this problem. For a comprehensive overview of the primary and secondary literature, see the two volumes by Hans-Josef Klauck (Apocryphal Gospels: An Introduction, Brian McNeil, trans. [London and New York: T&T Clark, 2003] and The Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles: An Introduction, Brian McNeil, trans. [Waco, TX: Baylor Univ. Press, 2008]) or the shorter treatment by Tony Burke (Secret Scriptures Revealed: A New Introduction to the Christian Apocrypha [London: SPCK and Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2013]).

2.

For further details about the formation of the canon, as well as challenges to the notion of the settling of the canon in the fourth century, see the work of Lee Martin McDonald, including The Biblical Canon: Its Origin, Transmission, and Authority, 3rd ed. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007) and The Formation of the Bible: The Story of the Church’s Canon (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2012).

3.

The Oxyrhynchus and other early apocrypha manuscripts are available, with photographs, in Thomas A. Wayment, The Text of the New Testament Apocrypha (100–400 C.E.) (New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2013).

4.

See James Robinson, The Story of the Bodmer Papyri (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2011).

5.

Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (New York: Vintage Books, 1979) was an early and prominent voice in this discussion.

6.

This re-evaluation has been brought to wider attention lately by Philip Jenkins in The Many Faces of Christ: The Thousand-Year Story of the Survival and Influence of the Lost Gospels (New York: Basic Books, 2015).

7.

Paul C. Dilley examines this phenomenon particularly for the Western church in “The Invention of Christian Tradition: ‘Apocrypha,’ Imperial Policy, and Anti-Jewish Propaganda,” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 50 (2010), pp. 586–615. Interest in this area of study has led to the creation of a new series from Penn State University Press called Inventing Christianity, edited by L. Stephanie Cobb and David L. Eastman.

8.

These two texts will appear in Burke and Landau, New Testament Apocrypha.

9.

Alin Suciu has become an expert on this literature. His Ph.D. dissertation, Apocryphon Berolinense/Argentoratense (Previously Known as the Gospel of the Savior). Reedition of P. Berol. 22220, Strasbourg Copte 5–7 and Qasr el-Wizz Codex ff. 12v–17r with Introduction and Commentary (Université Laval, 2013), includes a comprehensive survey of all the pseudo-apostolic memoirs (see pp. 75–91). The thesis will soon be published in E.J. Brill’s series Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae.

10.

See Nicola Denzey Lewis and Justine Ariel Blount, “Rethinking the Origins of the Nag Hammadi Codices,” Journal of Biblical Literature 133 (2014), pp. 399–419 and Mark Goodacre, “How Reliable Is the Story of the Nag Hammadi Discovery?” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 35 (2013), pp. 303–322.