The Sistine Chapel: A Glorious Restoration

ed. by Pierluigi De Vecchi

(New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994), 271 pp., 312 illus., $75.00

Spanning a void, two index fingers stretch toward each other, not yet touching, yet implying in the space between them God’s creative power. Incontestably the most famous image in Christian art, Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam from the Sistine Chapel ceiling in the Vatican has been copied, adapted, distorted—even spoofed.

Complaining that he was a sculptor, not a painter, Michelangelo accepted the commission to decorate the Sistine ceiling from Pope Julius in 1508, but only after numerous threats from the pope. Once he took the job, however, Michelangelo put all his prodigious energy into it, even designing the scaffold needed to render the paintings at the lofty height of 70 feet. In the incredibly short period of four years, he created the largest frescoed ceiling up to that time (132 feet by 44 feet). His contemporary, the painter, architect and art historian Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) exulted: “Painters no longer need to seek new inventions, novel attitudes, clothed figures, fresh ways of expression, different arrangements, or sublime subjects, for this work contains every perfection possible under those headings.”1

The recent, beautifully published The Sistine Chapel: A Glorious Restoration, offers an opportunity to revisit the ceiling, with its complex design and theological program, without traveling to Rome.2 From the first page, depicting the face of an old man—believed to be a self-portrait of Michelangelo—to the last, this book’s nearly 300 photos by Takashi Okamura glow with color and seem almost tactile in the way they record the restored painted surface.3 Next to the larger illustrations are apt biblical quotations (King James Version) and colorful quotations from Vasari’s “Life of Michelangelo Buonarrote.”

The ceiling, spread across a three-and-a-half-page foldout, divides into three sections. The outermost includes lunettes and triangular severies depicting the ancestors of Jesus (beginning with Abraham and ending with Joseph, as listed in Matthew 1:1–16). In four triangular spandrels in the four corners of this tier, the artist painted Old Testament scenes (depicting Judith and Holofernes,a David and Goliath, the Brazen Serpent and the Hanging of Haman), in which figures are miraculously saved from destruction. In the next tier appear seven enthroned prophets and five sibyls (see photo of the Delphic Sibyl).b At the summit a fictive architectural framework defines nine rectangles of alternating sizes that contain scenes from Genesis (see Sistine Chapel ceiling).c

The nine major scenes Michelangelo painted on the Sistine Chapel ceiling reveal his unique vision and religious devotion, as discussed in the sidebar to this article. Even though Michelangelo’s art was expressed through the human body full of life, art historian Kenneth Clark points out that he “became increasingly preoccupied with death; the soul must be judged; and he became more and more burdened by the consciousness of sin.”4 How appropriate, then, for him in his 60s to be commissioned to paint on the back wall the Last Judgment as the concluding scene in this extraordinary chapel of artistic miracles.

While the photo captions in The Sistine Chapel: A Glorious Restoration briefly mention the theological program behind the paintings, the book is devoted to more technical matters of how (rather than why) Michelangelo painted the ceiling. The book begins with an account of the cleaning by the late restoration supervisor, Carlo Pietrangeli, general director of Papal Museums, followed by nine articles by scholars who recreate Michelangelo’s methods, intentions and successes in painting the Sistine ceiling.

Michelangelo spent 520 days painting the entire ceiling, using the buon fresco (true fresco) technique, applying water-based pigments directly to wet plaster, writes chief restorer Gianluigi Cola-lucci in his article on the artist’s methods. Each day, Michelangelo plastered over the area to be painted that session. By noting discrepancies in the thickness of these plaster patches, restorers could determine the scope of each day’s work, or giornata. Michelangelo chose color pigments well suited to long-lasting buon fresco, and, contrary to the theory of conservative artists and Renaissance scholars, he did not tone down bright colors with a layer of glue, notes Colalucci.

In December 1509 Michelangelo dismissed the five assistants he had called to Rome from Florence, writes Fabrizio Mancinelli, who directed the restoration of the ceiling. Although individual hands are not distinguishable in the frescoes, Michelangelo was, apparently, disappointed with their work and discharged them. Soon after, Michelangelo completed the first half of the ceiling. His scaffolding was removed, and the artist could observe his work from the floor. The result: Halfway across the ceiling Michelangelo shifted to a larger scale, used fewer figures and, the restoration reveals, executed his figures more rapidly. He continued to work solo until he completed the ceiling in 1512.

Editor Pierluigi De Vecchi writes that the effect of unity and harmony created by the artist “relies as much on the painted architectural structure as on the relationships between sizes, gestures, and rhythms established by the placement across the ceiling of figures outside the narrative scenes.”5 These figures, often painted to look like statues, include ten pairs of ignudi, or young nude males, who flank the five smaller Genesis scenes at the center of the ceiling. (The ignudi are visible in the Sistine Chapel ceiling.) Seated in active poses on plinths that appear to jut out from the ceiling, the ignudi support imitation bronze medallions depicting scenes from Genesis, Samuel, Kings and Maccabees. Below the ignudi appear putti (naked babies), painted as high-relief marble statues. Writhing bronze-like male nudes, sometimes interpreted as devils, Michelangelo’s equivalent of medieval gargoyles, occupy the spandrels above the ancestors of Jesus.

Examining the clothing worn by the ancestors of Jesus, intended as biblical costumes, Edward Maeder, curator of Costumes and Textiles at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, points out various anachronisms: Many of the ancestors wear yellow garments and head coverings, both of which European Jews were required to wear at various times and places during the Middle Ages. The wife of Mathan (Joseph’s grandfather) wears a headpiece adapted from hats associated with Armenian Jews in late-15th-century Venice. In the paintings of Jesus’ ancestors, Maeder identifies 19 garments made of sarsenet, or “shot” silk, a shimmering textile in which the warp is one color and the weft another, causing the fabric to appear one color from one angle and another from a different angle. Popular, inexpensive and easily available in the 16th century, the fabric may have been introduced to Europe by Crusaders returning from the Holy Land; in Renaissance painting, shot silk often appears in clothing of people from the East, such as the magi.

Thirty years after completing the ceiling, Michelangelo painted his monumental Last Judgment on the Sistine Chapel’s eastern wall. A whirling composition dominates this fresco (measuring 591 square feet) of Jesus separating the elect from the damned. “In this work,” wrote Ascanio Condivi, the artist’s 16th-century biographer, “Michelangelo expressed all that the art of painting can do with the human figure.”6 Others, however, accused the artist of obscenity and monotony, which led, shortly after Michelangelo’s death, to the painting of loincloths over male genitalia by Daniele da Volterra, who ever afterwards was known as the “breeches painter.” The nudity of the figures, writes Pierluigi De Vecchi in The Sistine Chapel, was meant to emphasize the redemption of the body on the day of resurrection.

The Last Judgment was still being cleaned and restored at the time of this book’s publication, although the work is now complete and the loincloths have been removed. The restoration team determined that, despite the awkward and often damaging attempts to clean and restore the Last Judgment in the past, the fresco remains in excellent condition. Using seven colors, Michelangelo painted the entire wall in 450 days, creating cartoons—or full-scale preliminary drawings—for all the principal figures. Although he continued to use buon fresco, the artist occasionally painted a secco (on dry plaster) and added impastos (pigments applied thickly) rather than the transparent colors of the ceiling.

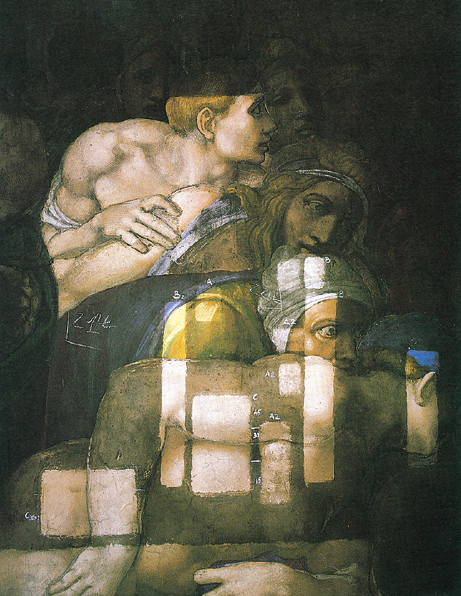

An illustration of tests being conducted on a segment of the Last Judgment reveals the dirt and grime on the fresco before cleaning (see Michelangelo’s Last Judgement). It reminds me of the transformation brought about when Rembrandt’s famous Nightwatch (painted in 1642) was cleaned in 1946–1947. The scene was discovered to be an early morning scene, thus a “Daywatch”! Does the fact that this volume came off the press before the Last Judgment was completely cleaned mean that another volume is in the offing?

Missing in the volume are photos of the technicians at work cleaning the Sistine Chapel ceiling, such as those published in David Jeffery’s most informative article, “A Renaissance for Michelangelo,” published in The National Geographic.7 Seeing the grand scale of the paintings beside the workers makes Michelangelo’s achievement even more astonishing. The infrared and ultraviolet photographs that accompany Jeffery’s article add considerably to the analysis.

Some scholars and artists opposed the restoration. In 1986 and 1987 several American scholars and artists wrote letters to Pope John Paul II asking him to suspend the cleaning process immediately until all data could be thoroughly reexamined. One letter was signed by artists Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Robert Motherwell, Christo and Andy Warhol, the latter having died before the letter was delivered. The art historian who protested most vehemently was Professor James Beck, head of the Art History Department at Columbia University.8 Arguing that delicate glazes and final touches applied by Michelangelo were being removed, he proclaimed the cleaning a disaster.d

Now the protests are quietly fading away. A new evaluation of Michelangelo as an extraordinary colorist is emerging. To grasp Michelangelo’s true intention, John Shearman reminds readers of The Sistine Chapel that one must observe the frescoes under natural lighting from the floor of the chapel. The restoration’s critics, Shearman suggests, made their judgments by looking at color photographs rather than viewing the frescoes in the setting in which Michelangelo painted. As meant to be viewed, however, the expressions and the action are exceptionally legible.

Proof of Michelangelo’s ability to use natural color, vivid yet harmonious, is there for scholars and public alike to see, as evidenced in the new book. The procedures used in cleaning and restoration at last seem justified.9 We anxiously await the publication of a concluding volume on the restored eastern wall. Then the world’s art critics can truly make their Last Judgment!

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Although Jews and Protestants number the Book of Judith, which includes the story of Judith and Holofernes, among their apocrypha, Catholics consider it canonical. Thus it would have been part of Michelangelo’s Bible.

Sibyls were women in the ancient world with the gift of prophecy. The church fathers recognized several of these women as prophets heralding the coming of Jesus.

For a description and plan of the ceiling and its parts, see Suzanne F. Singer, “Understanding the Sistine Chapel and Its Paintings,” BR 04:04.

For a full description of these debates, see Jane Dillenberger and John Dillenberger, “Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling—To Clean or Not to Clean,” BR 04:04.

Endnotes

This is actually the second book on the restoration produced by the Nippon Television Network. The first in the series, The Sistine Chapel: Michelangelo Rediscovered (London: Muller, Blond & White, 1986), dealt with the historical setting in Michelangelo’s Rome, the history of the earlier decoration in the Sistine Chapel, the theology behind Michelangelo’s ceiling, his later Last Judgment fresco (on the end wall above the Sistine Chapel altar) and the painting of the lunettes, the semicircular scenes that make up the lowest section of the ceiling decoration. Only the lunettes had been cleaned and restored when this volume went to press in 1986. The current issue was published in Italian six years later (the English edition appeared in 1994), after the entire ceiling had been cleaned and while the cleaning of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment fresco was under way.

Pierluigi De Vecchi, “The Syntax of Form and Posture from the Ceiling to the Last Judgment,” in The Sistine Chapel: A Glorious Restoration, ed. De Vecchi (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994), p.224.

James Beck, Art Restoration: The Culture, the Business and the Scandal (London: J. Murray, 1993).