Editor’s Note: This article contains images of human skeletal remains.

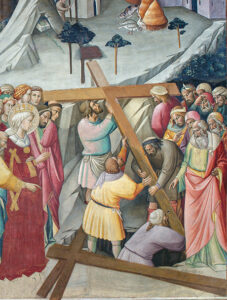

The nails of the cross are the stuff of legend. According to the fourth-century bishop Ambrose of Milan, Constantine’s mother Helena, on her pilgrimage to the Holy Land, discovered the true cross and the nails used during Jesus’s crucifixion. She then had one of the nails fashioned into a bejeweled diadem, writes Ambrose, and another one incorporated in a bridle for Constantine’s horse (On the Death of Theodosius 47). Mentioned a few times by the early church fathers (Ignatius, Letter to the Smyrnaeans 1.1; Justin Martyr, First Apology 35), it was Helena’s mythic journey and discovery that helped solidify the nails as part of the evolving Christian lore surrounding the crucifixion. Today, numerous relics that claim to be one of the nails of the cross are considered sacred by both Catholic and Orthodox Christians.

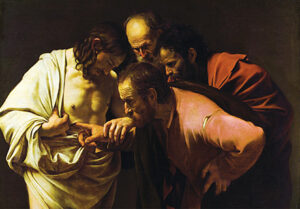

Surprisingly, however, the detailed crucifixion narratives in the Gospels (Matthew 27:27–44; Mark 15:16–32; Luke 23:26–43; John 19:16–37) are conspicuously silent about what exactly was used to secure Jesus to the cross. The Greek verbs used to describe the crucifixion, namely stauroō and kremannymi, mean “to hang on a stake” or simply “to hang up,” respectively. Neither implies how the victim was fastened to the cross. Moreover, the single occasion where Jesus’s nail wounds are explicitly mentioned is in the “Doubting Thomas” episode (John 20:24–29), an account unique to John’s Gospel. There, the disciple Thomas, who is missing during Jesus’s first appearance (v. 24), would not believe Jesus had risen without seeing—and placing his finger on—the “mark of the nails.” The other Gospels make no mention of the wounds, and all the disciples, including Thomas, appear to be present when Jesus first appears (see Mark 16:14). Therefore, outside of the Doubting Thomas scene, the New Testament does not explicitly mention Jesus’s nail wounds, (Colossians 2:14 refers to the titulus, “which proclaimed the nature of the crime”).1

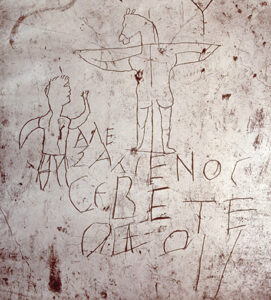

Despite this ambiguity in the gospel accounts, archaeology has provided the prospect of finding additional evidence for crucifixion or, at least, how it was typically carried out. In 1968, archaeologists struck gold, metaphorically speaking, at the ancient Jewish burial site of Givat ha-Mivtar, Jerusalem.a A calcified heel bone with an almost 5-inch nail driven through it was uncovered at the bottom of an undecorated ossuary (bone box) typical of the late Second Temple period, with the mixed human remains inside dating from the first century BCE to the time of the First Jewish Revolt (66–74 CE). Shallowly etched into the ossuary were two Hebrew inscriptions, the first giving the name “Yehohanan” and the second, carved just to the left of the first, reading “Yehohanan ben hagaqol.” While some have taken hagaqol to be a patronym, Yigael Yadin argued it should be read as h‘qil, describing how Yehohanan was crucified with his “knees apart.”2 This style of suspension may be corroborated by several ancient depictions of crucifixion, including the Puteoli and Alexamenos graffiti, as well as the Pereire gem.b

The area of Givat ha-Mivtar held more surprises. At the so-called Abba cave, just a short distance away, archaeologists found skeletal remains dating to the first century BCE, including a decapitated skull and finger bones with associated iron nails. Some scholars suggested these could be the remains of Mattathias Antigonus, the last Hasmonean ruler (r. 40–37 BCE), who, according to historical sources, was executed by Marc Antony, either by beheading (Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 15.9) or crucifixion (Dio Cassius, Roman History 49.22.6).3 Notably, however, even though Dio Cassius mentions that Antigonus was “bound to a cross and flogged,” there is no reference to the use of nails. Furthermore, according to physical anthropologist Patricia Smith, the nails found in the Abba tomb “did not penetrate the bone,” suggesting they were likely not used to crucify the deceased.4

In 2017, a striking parallel to the heel bone from Givat ha-Mivtar was discovered more than 2,000 miles away in Fenstanton, England. During the cleaning of skeletal remains from a Roman-era gravesite, archaeologists identified a heel bone pierced by a nail.c The site and remains date to between the second and fourth centuries. The pierced heel bones from Jerusalem and Fenstanton join only two other archaeologically attested cases of crucifixion, one in Egypt and the other in Italy, although in both cases, the heel bones showed only the trauma from crucifixion and did not have the nails preserved.5 Importantly, however, the examples from outside Israel date to after the first century CE. Within Israel, the heel bone from Givat ha-Mivtar likely dates to just before the First Jewish Revolt.

Equally significant, our historical and textual sources from the late Second Temple period are quite vague on how crucifixion was carried out, at least until the time of the First Jewish Revolt. The Commentary on Nahum, a first-century BCE Dead Sea Scroll text that attempts to contemporize the biblical prophet, references the “seekers of smooth things” who are hung alive on trees by the “lion of wrath” (frags. 3–4, I.7) which may be an allusion to the crucifixion of Pharisees by the Hasmonean ruler Alexander Jannaeus (Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 13.380). Similarly, the Temple Scroll, discussing those who commit crimes against the community, permits hanging perpetrators “on a tree alive until dead” (64.7–11). Both accounts use the ambiguous Hebrew verb talah (“to hang”) and neither references the method of suspension. The historian Josephus employs only slightly more precise terminology to describe crucifixion. His use of the Greek verb “to crucify” (stauroō, anastauroō) means to suspend someone from a wooden stake, with no indication of the method or tools used.

In discussing various Roman atrocities during the First Jewish Revolt, however, Josephus noticeably uses a different verb, namely, “to nail” (proseloō), when describing crucifixion. In particular, he depicts the Roman procurator of Judea, Gessius Florus (64–66 CE), as having “nailed” some of Judah’s highest-ranking citizens to the cross (War 2.308). During the destruction of Jerusalem, Roman soldiers likewise “nailed” those they caught to crosses (War 5.451). In both accounts, Josephus jettisons the verb “to crucify” and instead describes crucifixion quite simply as “nailed … to crosses.” Various references in the Mishnah seem to indicate that crucifixion with nails continued well after the revolt. The second-century teacher Rabbi Meir, for example, is recorded as allowing the “nail from a crucified victim” to be used for healing (m. Shabbat 6:10).

If the Romans did indeed change their execution style during and after the First Jewish Revolt, this could suggest that earlier crucifixions, including during the time of Jesus, were carried out with ropes or other similar material. In fact, Luke’s use of the word “to hang” (kremannymi) to describe one of the crucified thieves (Luke 23:39) as well as Jesus’s own death (Acts 5:30) seems to imply ropes. Furthermore, this use of kremannymi is equivalent to the language we find in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Josephus, at least in references to crucifixion before the time of the First Jewish Revolt.

Yet if nailing was not common in Judea before the revolt, why does John’s Gospel explicitly mention Jesus’s nail wounds in the Doubting Thomas episode? Several reasons seem plausible. First, the author (or his audience) was perhaps located in a region, such as Ephesus or elsewhere in Asia Minor, where nailing of the hands was well known. Second, there are aspects of John’s crucifixion and resurrection accounts that are unique. John alone describes the piercing of Jesus’s side (19:34) and views it as a fulfillment of prophecy, namely, “they will look on the one whom they have pierced” (19:37; cf. Zechariah 12:10). John also appears to be rewriting Luke 24:36–43, where the disciples are directed to “touch” and “see” Jesus’s hands and feet. Of course, it is clear in Luke (v. 39) that Jesus’s hands and feet are intended to prove the resurrection of his body and not to demonstrate the nail wounds. Therefore, John might be creatively weaving together these elements, portraying the crucifixion as real, even a fulfillment of Zechariah’s prophecy, for a community who had to believe without seeing.

Most important, in the Doubting Thomas episode, John’s Gospel preserves a style of crucifixion that does not appear to predate the First Jewish Revolt, specifically in Judea. Therefore, this account may have come from a time after the revolt or somewhere in the Diaspora where nailing was more common, while John’s crucifixion story was adapted from his sources, likely the other Gospels.

Crucifixion was a common form of punishment in the Roman world. Yet when ancient texts and archaeological evidence are examined together, it appears that nailing a victim to a cross may not have been as common as most people think. And it might have been introduced in Judea only after the time of Jesus.

For my tio Arnaldo Arroyo, who will not get to see this published but whose discussions about the Bible gave me agency to look at its narratives from different perspectives. Te amo y te extraño, tio.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. Vassilios Tzaferis, “Crucifixion—The Archaeological Evidence,” BAR, January/February 1985.

2. Ben Witherington III, “Images of Crucifixion: Fresh Evidence,” BAR, March/April 2013.

3. See Strata, “Roman Crucifixion in Britain,” BAR, Fall 2022.

Endnotes

1. See Gunnar Samuelsson, Crucifixion in Antiquity: An Inquiry into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011), p. 294; and John Granger Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014), p. 110. First Peter 2:24, Galatians 6:17, and Revelation 1:7 are either alluding to the Hebrew Bible or referring generally to “wounds.”

2. Yigael Yadin, “Epigraphy and Crucifixion,” Israel Exploration Journal 23.1 (1973), pp. 19–22.

3. Yoel Elitzur, “The Abba Cave: Unpublished Findings and a New Proposal Regarding Abba’s Identity,” Israel Exploration Journal 63 (2013), pp. 83–102; see also James Tabor, “The Abba Cave, Crucifixion Nails, and the Last Hasmonean King,” Taborblog (online), April 3, 2016.

4. Patricia Smith, “The Human Skeletal Remains from the Abba Cave,” Israel Exploration Journal 27.2/3 (1977), pp. 123–124.

5. See Emanuela Gualdi-Russo et al., “A Multidisciplinary Study of the Calcaneal Trauma in Roman Italy: A Possible Case for Crucifixion?” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, April 2018, doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0631-9.