018

019

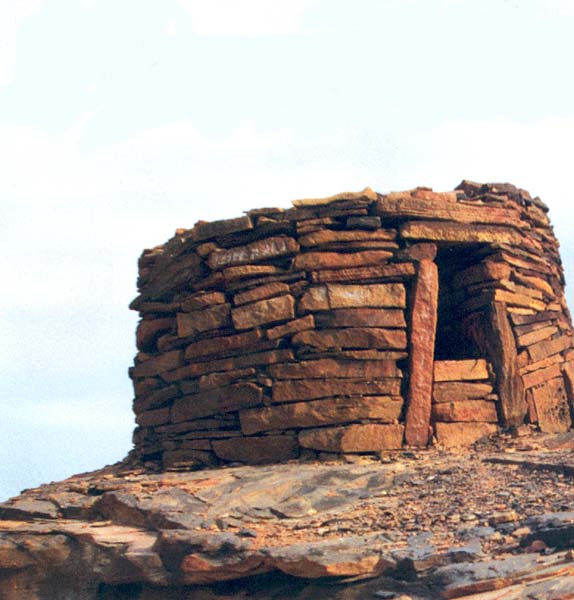

They look like flattened igloos—mysterious ancient round burial tombs, called nawamis, in southern Sinai. To Canadian archaeologist Charles Currelly, who studied them in 1904 as part of British archaeologist Flinders Petrie’s expedition to Sinai, these 6-foot-high sandstone structures resembled beehives scattered across the desert floor.

020

Their name, nawamis, means mosquito. According to Bedouin legend, the nawamis were built as protection against mosquitoes by the Israelites of the Exodus during their wanderings in Sinai. The Bedouin also give the more likely explanation that the term namusiyeh (plural, nawamis) refers to any separate or freestanding structure. We shall simply use nawamis to refer to one or many of these unusual structures.

From the burial goods and human remains found in the nawamis, we know that they were built around 5,000 years ago as tombs by nomadic herders. These remarkably preserved stone buildings are thus the world’s oldest remains of a pastoral nomadic society.

The bones in the nawamis were disarticulated (that is, separate from one another), which suggests that the tombs were used for secondary burials. Nomadic peoples did not always conveniently die near their burial grounds, and it would have been dangerous and unpleasant to transport decaying corpses over long distances. So the deceased would have been buried at the site of death and disinterred some time later for transport to the nawamis. The bones may well have been deliberately disarticulated for ease of transport.

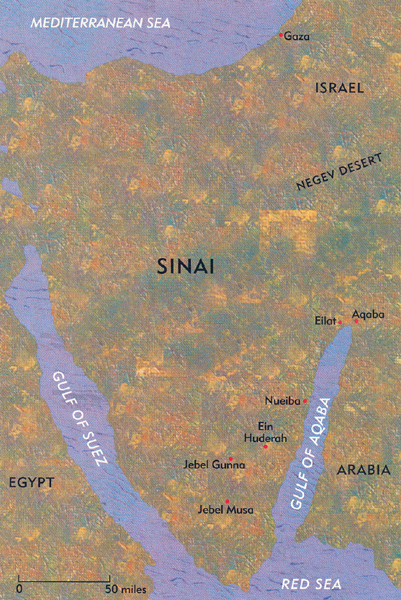

Nine groups of nawamis have been discovered in southern Sinai, creating a kind of ring around Jebel Musa, the 7,000-foot-high peak that is the traditional—although much-disputed—location of the biblical Mt. Sinai.

The people who built the nawamis would move seasonally with their herds of goats. In the heat of summer, they would climb high into the mountains to find pasture. During the bitterly cold winters, they would make their camps at lower altitudes. Most of the nawamis clusters are 2,400 to 3,000 feet above sea level.

The cluster we investigated most thoroughly, at Ein Huderah, was discovered in the late 1960s during a survey by Israeli archaeologist Beno Rothenberg. Located on the route between St. Catherine’s monastery at the foot of Jebel Musa and the resort village of Nueiba on the western shore of the Gulf of Aqaba, Ein Huderah lies between the mountainous limestone plateau of central Sinai and the 021high mountains of southern Sinai.

Rothenberg conducted his surveys while Israel controlled Sinai. At that time, I was appointed by the Israeli Department of Antiquities to serve as Archaeological Staff Officer for Sinai. Although international law does not allow new elective excavations to be undertaken in occupied areas, it does require the controlling power to perform a salvage excavation if a site is threatened. As soon as Rothenberg’s discovery became known, hundreds of tourists began making their way to Ein Huderah, where they enjoyed crawling through the narrow entrances of the nawamis. We were afraid that careless visitors would damage the ancient remains. A salvage dig was needed.1

From St. Catherine’s monastery, it took us the better part of two days in a jeep, crossing dunes and mountainous terrain, to reach Ein Huderah. We were so astonished by our first glimpse of the stone huts on top of a hill that we shouted with surprise as we ran up to them. They were extremely well preserved, so we didn’t think they could date earlier than the medieval period, or perhaps the Byzantine period. Here and there, however, we came across shell beads that hinted at a much earlier date.

We conducted a week-long salvage excavation in December 1971, and then another week-long excavation in the spring of 1973. We asked local Bedouin to assist in the excavations. They told us that they would carry baskets of excavated material from the nawamis, but they would not enter a tomb or touch the bones of the dead. Maybe this fear helped preserve the nawamis over five millennia.

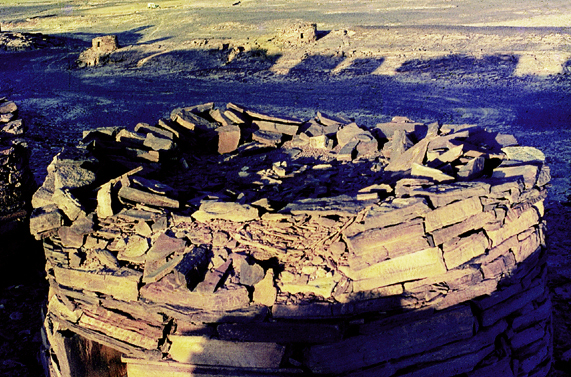

Of the 42 nawamis at Ein Huderah, 30 were clustered on a low, flat hill. The others were scattered about the sandstone plateau. Each building was circular, about 12 feet in diameter (from outer wall to outer wall) and 6 feet high, with a small entrance and a slightly concave roof.

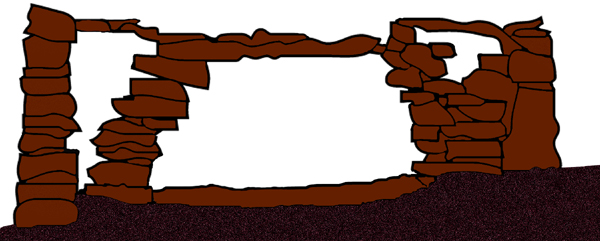

We investigated 24 of the structures, all well-built cylinders made from carefully selected, but not dressed, sandstone. The outer wall of each nawamis was built perpendicular to the ground. When the wall reached about 2 feet in height, the interior space was filled with gravel, and sometimes a floor of flat stone slabs was laid over the gravel. From this floor level, the outer wall was then continued straight up to the full height of the nawamis. An inner wall of stone slabs, abutting the outer wall, was built up from the gravel floor. This inner wall was constructed with a corbeling technique—so that each successive course of stone slabs jutted slightly more toward the center of the nawamis, eventually forming a partial 022interior dome (see drawing depicting corbeling technique). The opening at the top of this dome was then capped with a 3-foot-square slab of stone.

The outer wall of the nawamis rose 4 to 8 inches above the level of the capstone. The tomb builders then filled in any spaces between outer and inner walls with rubble, strengthening the structure and creating a shallow basin-shaped roof. The finished tomb—with its solid, finely constructed outer wall, its lovely circular shape and its spare desert surroundings—is an impressive monument for the dead.

This corbeling technique is well known from later periods. The founder of Egypt’s 4th Dynasty, Sneferu (2575–2551 B.C.), built the first Egyptian corbeled chamber in his North Pyramid at Dahshur, at the southern end of the Memphis necropolis. The nawamis are at least 500 years older than the North Pyramid; they thus provide some of the world’s earliest known examples of the use of corbeling, along with the roughly contemporaneous megalithic temples on the island of Malta.a No doubt the lack of wood in the desert motivated the nomads of Sinai to develop this elegant roofing solution.

Each nawamis has a small rectangular entrance, about 2 feet high and 1 foot wide, always facing west. The entrances 024were probably sealed with a blocking stone, though we found no sealed nawamis. These stones were likely removed in later times, either by grave robbers or by Bedouin who simply wanted to use the nawamis as tombs (one nawamis contained a skeleton that was less than 100 years old).

Let’s imagine what happened on a particular day more than 5,000 years ago in Sinai. Nomadic herders arrived with their flocks at Ein Huderah, carrying with them the bones of a deceased man from their tribe. After the man had died near a distant pasturing ground, his family had immediately buried him there. A year or more later, when the body had lost its soft organs, the family disinterred the skeleton and took its bones to their sacred burial site at Ein Huderah.

Although other families in the tribe owned nawamis, which they used to inter multiple family members, our recently aggrieved family had not yet built one and thus had their work cut out for them when they reached Ein Huderah. They would have assembled in the evening at the site of the proposed structure to mark the direction of the setting sun. Perhaps they drew a circle on the ground—a kind of floor plan—providing the dimensions of their nawamis. Perhaps they then drew a line from the center of the circle toward the setting sun, thus pointing out the entrance of the tomb. Perhaps they even performed a ceremony to honor the deceased. The next morning they began to gather the stones. Four or five men could have completed the nawamis in three to four days.

We are even able to suggest, from the apparent motion of the sun, the months when the nomads built their burial structures at Ein Huderah. The sun travels about 23 degrees north to south along the western horizon during the year—being farthest north at the summer solstice and farthest south at the winter solstice. So we calculated a line that passed from the center of each nawamis through the center of its entrance and on to the horizon. In 80 percent of the nawamis, the entrances were oriented toward the setting sun of July or August.

How do we date these enigmatic structures? How do we know that they were not built during the medieval or Byzantine periods, as we first suspected? The answer lies in the objects buried with the disarticulated bones in the nawamis. Our task was made more difficult, however, by the fact that each of the 24 structures we were examining had been disturbed in antiquity. This means that our dates for the nawamis remain somewhat speculative. To fix the dates of the tombs with certainty, we would need to find an undisturbed, sealed nawamis. Nonetheless, by sieving the sand and rubble inside the structures, we found evidence that had been overlooked until 025our salvage excavation.

The most numerous artifacts were necklace beads made from marine shells, fish teeth, carnelian, bone, ostrich shells and faience—the latter made from glazed pottery, probably acquired in Egypt by the nawamis builders. We collected well over 1,000 beads. The most common bead by far was made from dentalium, a mollusk with a tapering tubular shell (often called a tooth shell), found in the Red Sea.

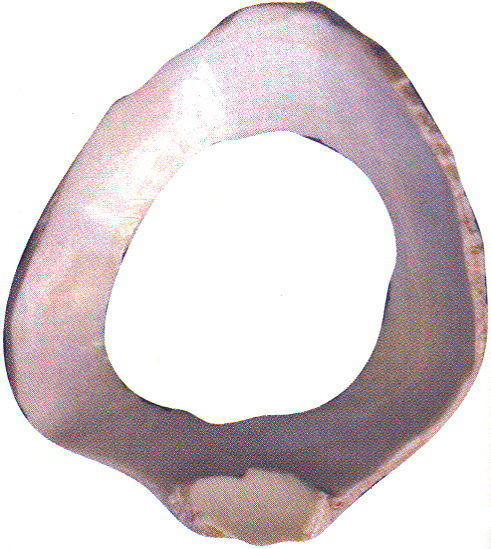

In a third of the nawamis, we found shell bracelets that had been cut from the mollusk Lambis truncata. This Red Sea mollusk, also known as the Giant Spider Conch, grows to as large as 16 inches long and 8 inches wide. Lambis bracelets are known from the Chalcolithic period (c. 4500–3500 B.C.) site of Tell Abu Matar, near Beer-Sheva, Israel, and from the Chalcolithic/Early Bronze sites (late fourth millennium B.C.) of Bab edh-Dhra in Jordan and Tell el-Farah (North) on the West Bank. Thus our Lambis bracelets provide a rough chronological indicator for dating the nawamis to the fourth millennium B.C.

Support for this date also comes from about 100 flint transverse arrowheads found in most of the nawamis we studied. Unlike the more familiar arrowhead whose point forms the end of the projectile, transverse arrowheads are “backward”—with the point of the triangular arrowhead attached to the arrow’s shaft and the wide edge of the arrowhead forming the end of the projectile. These arrowheads are quite common at sites in the Egyptian Delta, the Mediterranean coast of Egypt, Sinai and southern Israel—and they all date to the fourth millennium B.C. Transverse arrowheads are also depicted in early Egyptian art, such as on the Hunter’s Palette (also called the Lion Hunt Palette) from the late pre-dynastic period (c. 3000 B.C.). Today transverse arrowheads are sometimes used to hunt small birds, in order to disable but not kill the creatures.

We also found flint tools, such as borers and scrapers, and a few copper objects, including an ax head and four arrowheads. We found hardly any pottery, which is not surprising for a nomadic culture that does not carry breakables in moving from site to site. Of the eight sherds we found in the nawamis, five were Byzantine and three were probably Early Bronze Age II (3000–2700 B.C.).

To test the fourth-millennium B.C. date provided by the Lambis bracelets and transverse arrowheads, we had radiocarbon tests performed on the scant organic finds. Charcoal found in the nawamis gave a carbon date of the fourth millennium B.C.

Although we could not date the human bones, there was much to learn from them. Of the 24 nawamis we investigated, 20 contained human bones—the remains of men, women and children as young as 2 026years old. Younger infants may have been buried beneath the floors of family living areas rather than in tombs—a practice known from the Chalcolithic site of Tuleilat el-Ghassul, just north of the Dead Sea in Jordan. The greatest accumulations of bones in the Ein Huderah tombs were near the walls. Apparently newly reinterred bones were placed at the center of the nawamis, which had been cleared of older burials by moving them aside.2

Only three of the 29 adults we found lived more than 40 years. All adult teeth were severely worn down, perhaps as a result of a diet high in coarse flour and, inevitably, wind-blown sand. Physical anthropologist Patricia Smith determined that several adults suffered from severe osteoarthritis in their spine and joints, which would have made it difficult, if not impossible, for them to walk.

Life was harsh and relentlessly demanding for these herders, who moved from place to place constantly searching for grazing land for their goats. Why, we asked ourselves, did they bury hard-to-come-by goods—even valuable copper arrowheads—with the dead rather than pass them on to the living? Clearly they believed that the dead needed their beads, bracelets and arrowheads in the afterlife.

We would later see this belief in an afterlife fully developed in pharaonic Egypt. Egyptian burial practices resembled those of the nawamis, especially in their orientation toward the setting sun. The west, in Egyptian belief, was the land of the dead, where every evening the sun “died,” only to be “reborn” in the morning in the east. Even in pre-dynastic Egypt (last centuries of the fourth millennium B.C.), bodies were laid to rest in burial pits with their heads facing west.

We admit that we cannot make tight connections between the nawamis culture of Sinai and the cultic practices of Egypt. Perhaps this poor, spare desert society in Sinai and the resplendent dynastic world in Egypt simply arrived by coincidence at similar beliefs about life and death.

The nawamis culture was a flash in historical time, lasting only about 300 years. When the Egyptians began to build the great pyramids in the mid-third millennium B.C., the nomads who buried their 062dead in strange stone desert huts had already lived out their history—or at least what we know of it. The pyramids, with all their grandeur and majesty, seem built for eternity. What is astonishing is that the small, modest stone structures in Sinai also still stand strong in the battle against leveling time.

They look like flattened igloos—mysterious ancient round burial tombs, called nawamis, in southern Sinai. To Canadian archaeologist Charles Currelly, who studied them in 1904 as part of British archaeologist Flinders Petrie’s expedition to Sinai, these 6-foot-high sandstone structures resembled beehives scattered across the desert floor. 020 Their name, nawamis, means mosquito. According to Bedouin legend, the nawamis were built as protection against mosquitoes by the Israelites of the Exodus during their wanderings in Sinai. The Bedouin also give the more likely explanation that the term namusiyeh (plural, nawamis) refers to any separate or freestanding structure. We shall simply […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Linda C. Eneix, “The Twin Temples of Gozo,” Destinations, AO 04:04.

Endnotes

See Ofer Bar-Yosef, Anna Belfer, Avner Goren and Patricia Smith, “The Nawamis near ‘Ein Huderah (Eastern Sinai),” Israel Exploration Journal 2–3 (1977), pp. 65–88.

This was confirmed by our later excavation of nawamis at Gebel Gunna, about 20 miles east of Ein Huderah. Almost all of the bones we found were disarticulated and lying near the outer walls. See O. Bar-Yosef, Anna Belfer-Cohen, A. Goren, I. Hershkovitz, Ornit Ilan, H.K. Mienis and B. Sass, “Nawamis and Habitation Sites near Gebel Gunna, Southern Sinai,” Israel Exploration Journal 3–4 (1986), pp. 121–167.