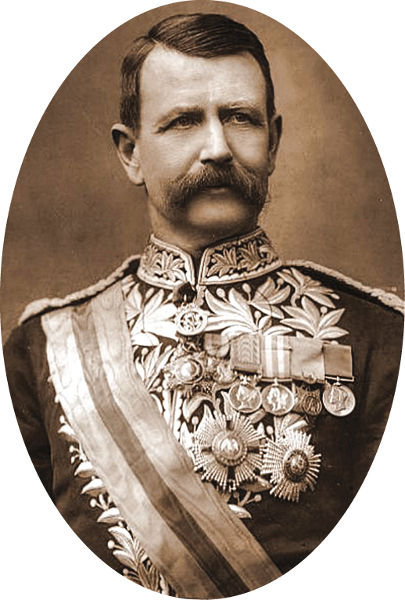

On November 20, 1867, the great Charles Warren, later Sir Charles Warren, the famous English engineer who conducted the first major excavations near Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, uncovered an impressive hall about 400 feet from the Temple. For some unknown reason, he named it the Free Masons Hall, or simply the Masonic Hall. It immediately became a sensation, attracting many visitors, both women and men.

We believe this structure was an elegant dining hall that dates to King Herod’s time.

About a century after Warren discovered the hall, it was investigated by William F. Stinespring in 1966. But it was only after the Six Day War in 1967, when the Old City of Jerusalem came under Israeli control, that the hall was cleared from the fills that had accumulated over centuries, the plaster covering its walls was removed and it was further explored by Meir Ben-Dov, Dan Bahat and Aren Maeir.

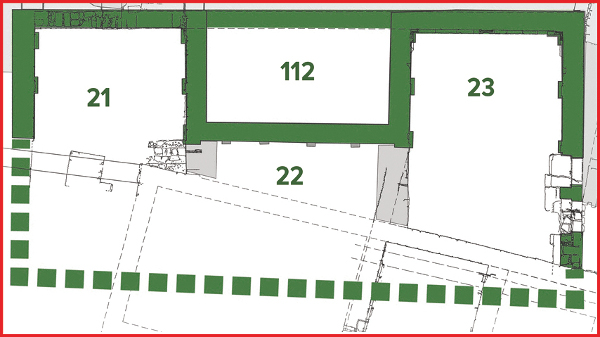

Between 2007 and 2012, Alexander Onn—on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority and on the initiative of the Foundation for the Heritage of the Western Wall—excavated another room identical to the Masonic Hall to its west as well as an elaborate fountain room and a water reservoir between the two side halls.

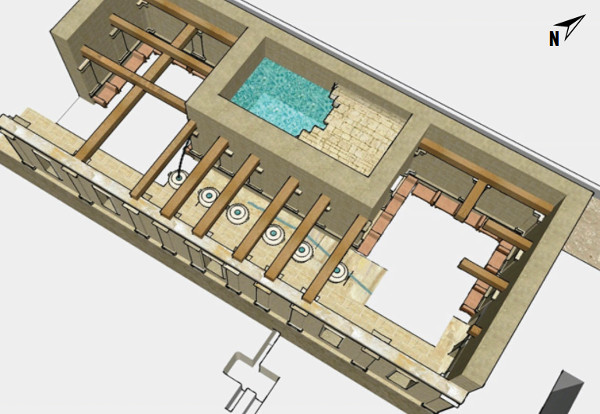

After our recent re-examination, we can suggest that the building, of which the rooms are part, was actually a royal banqueting complex equipped with a fountain (Room 22 on the plan).1 The two side halls (Rooms 21 and 23) were triclinia (dining rooms) with reclining couches arranged along the walls. This identification is based on the architecture, the wall decoration, comparison to similar buildings and the elimination of other possible functions of the halls, as the complex was neither a domestic structure, storage facility, religious structure, fortification nor a nymphaeum (decorative fountain), as has been suggested in the past.

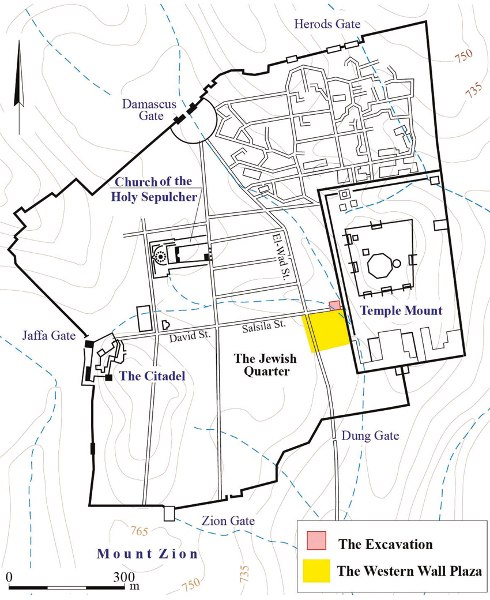

The banquet building is about 75 feet from the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. The building’s floor lies about 50 feet below the level of the Street of the Chain. The building is composed of two identical elaborate halls and a fountain room in between. The walls were adorned with attached pilasters resting on a raised podium crowned with a decorative cornice and supporting plain-faced Corinthian capitals. It went out of use in about 33 C.E., presumably due to damage caused by an earthquake in the year of “the Crucifixion of Christ” (33 or 34 C.E.).

The stones used on the outside of the building have chisel-drafted margins resembling those of the Western Wall, but smaller in size.

Couches were set along the walls of the two side halls (Rooms 21 and 23). Since couches were generally movable and made of perishable materials, they are not generally preserved in situ, but in our case traces were left on the stone walls: A rectangular depression in the southern end of the western wall of Room 21 marks the leg-end of the last couch in that hall, and a curvilinear depression in the southern end of the eastern wall of Room 23 marks the head-end of the first couch in that hall.

In modern scholarship, a dining room is usually called a triclinium, even if there were more than three reclining couches (klinai, in Greek) in the room.

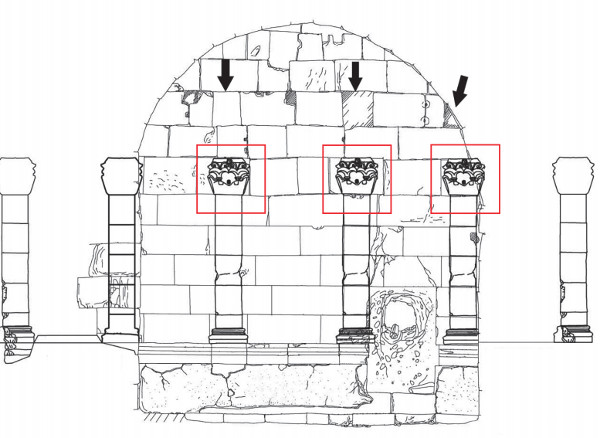

The southern part of the complex has entirely collapsed. The façade of the room separating the two triclinia was adorned with six attached pilasters. Holes were cut in the center of each of their capitals, and a lead pipe was set in each. These six capitals served as fountain heads. Water flowed out through the pipes from a reservoir that was built behind the decorative façade. Higher up on the fountain wall were recesses into which were set roofing beams.

The architectural style, magnificence and sophistication of the building, with its integrated fountain, suggest that it was sponsored by Herod himself. It stands as an independent structure next to the road that led from the upper city eastward to the Temple Mount. Its location along the road that continues to the Temple Mount suggests that it served guests of the king or of the city before they entered the Temple precinct. Visitors may have included foreigners who wanted to admire the splendor of the Temple and its ceremonies. The building may also have served as a meeting place for the nonpriestly chiefs of the Israelites who served at the Temple.

The complex was apparently in use for about 60 years. It was partially destroyed some 40 years before the Temple’s ultimate destruction by the Romans in 70 C.E.

This composite triclinium is arguably the most splendid Herodian building to have survived the Roman destruction of Jerusalem.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

1.

The findings were published in full in Joseph Patrich and Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah, “The ‘Free Masons Hall:’ A Composite Herodian Triclinium and Fountain to the West of the Temple Mount,” New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and Its Region 10 (2016), pp. 15–38; Alexander Onn and Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah, “Jerusalem, The Western Wall Tunnels,” Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel 128 (2016), www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=25120&mag_id=124.