On the Road and on the Sea with St. Paul

Travelling conditions in the first century

038

In the Acts of the Apostles, we are told that Paul made three missionary journeys. In almost every introduction to the New Testament I have seen, the author discusses St. Paul’s journeys in terms of places and dates; his concern is to establish the location of the cities Paul visited and to fix the exact time he visited them. But when Paul himself speaks of his travels he emphasizes, not the “where” or the “when,” but the “how.” For instance, in defending himself against attacks on his authority in the church of Corinth, Paul writes:

“Three times I have been shipwrecked; a night and a day I have been adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from robbers, … danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brethren; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, in hunger and thirst, often without food, in cold and exposure” (2 Corinthians 11:25–27).

By this catalogue of hardships, the Apostle underlines his dedication to his ministry. But for us, too much is left unsaid for the evocative potential of Paul’s description to be fully realized. Paul’s contemporaries could easily have filled in the picture from their own experiences. We who travel at great speed and in security and comfort, however, need to transport ourselves consciously to a very different world if we are to appreciate the conditions under which Paul passed a great part of his life, and that contributed to the experiences that became integral to his theology.

Since Paul himself gives us no details, we must extrapolate; what he encountered would have been similar to what others, who lived a century before or after, experienced.

With minor localized exceptions, peace reigned throughout the Roman Empire for 200 years after Augustus Caesar’s (Octavian’s) accession to power in 30 B.C. During this time, travel conditions remained the same. From scattered references by Greek and Roman writers, we can recreate a rather detailed picture of what it was like to travel in the first century A.D. This has been done in an excellent study entitled Travel in the Ancient World by Lionel Casson (London: Allen & Unwin, 1974). But Casson’s material needs to be supplemented by information from a source that he inexplicably ignores; that is, from The Golden Ass,1 a Latin novel written by Apuleius, who was born about 123 A.D. This novel describes the adventures of Lucius, a man turned into a donkey, who undergoes many misfortunes at the hands of a series of owners before finally recovering his own form as a man. The action takes lace in the area between Corinth and Thessalonica, where Paul also went, and provides invaluable 039insights into life outside the major cities, as well as conditions of travel.

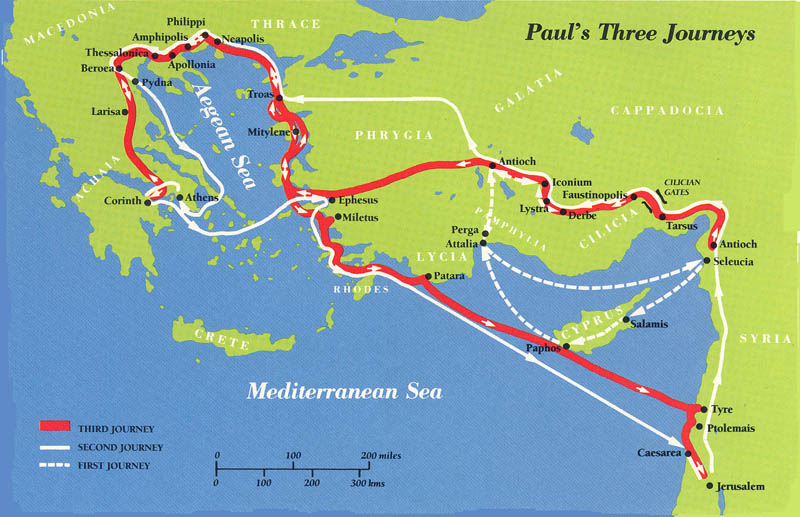

Paul’s first missionary Journey took him from Syria to Cyprus and then to Pisidia (part of modern Turkey) (Acts 13–14). His second journey, across Asia Minor into Europe, is narrated by Luke in Acts 15–18. The journey can also be reconstructed from hints scattered throughout the Pauline Epistles. The only difference between the account in Luke and in the Epistles is the date. Luke places Paul’s journey after the Jerusalem conference (Acts 15), which took place in 51 or 52 A.D., when the apostles worked out a compromise permitting Jewish and Gentile Christians to eat together. From Paul’s own letters it is clear that this journey must have taken place before the Jerusalem conference, probably between 45 and 51.2 On his third journey, Paul revisited many of the cities where he had preached during his second journey (Acts 18:22–21:16).

In Paul’s time, as today, how you traveled depended on how much money you could afford to spend. Paul was not a rich man. The impression he gives in his letters is that he had no significant personal financial resources. He seems to have had nothing beyond what he could earn and the sporadic gifts sent to him by various churches (2 Corinthians 11:8–9; Philippians 4:14). As an itinerant artisan, a tent-maker (Acts 18:3), he was far better off than an unskilled worker of the laboring class, but no artisan became rich. It would have been as much as Paul could do to earn his daily bread, even if he had enjoyed a stable situation with a regular clientele. But Paul garnered much of his work from fellow travelers on the road, or he had to begin anew in a strange city where he had no reputation to attract business.

In these circumstances, Paul certainly traveled on foot. A large selection of wheeled vehicles was available to travelers, but to rent or buy one would 040have been beyond his means. What about a horse? Except by military dispatch riders, horses were not used to travel long distances. Riding came easily only to those born on horseback, for saddles were rudimentary, and stirrups unknown. A donkey could certainly have borne some of Paul’s baggage, but this would only have increased his expenses without increasing his speed. Moreover, a donkey could be requisitioned by any soldier or official who needed it. Several decades earlier, the philosopher Epictetus had advised donkey owners to surrender their beasts immediately on being requested to do so, in order to avoid being beaten up by soldiers (Discourses 4:1.79). Requisitioning by soldiers was so common that it is even illustrated by an episode in Apuleius’s Golden Ass (9:36–10:12).

How far could Paul expect to go in a day? In some travel narratives the number of days needed to cover a known distance is recorded; the average daily distance is about 20 miles.3 An anonymous traveler known as the Bordeaux pilgrim, who visited the Holy land in 333 A.D., kept a famous diary that has survived. From Faustinopolis to Tarsus he followed the Roman road laid down when Pompey moved his legions into the East m 63 B.C., through the Cilician Gates. Paul took this road in reverse when he traveled from Tarsus to Galatia. According to data given by the Bordeaux pilgrim, the distances were as follows:a

|

City of Tarsus |

to Inn at Mascurinaer—12 Roman miles

|

|

Inn at Mascurinae

|

to Post at Pilas—14 Roman miles

|

|

Post at Pilas

|

to Inn at Podans—12 Roman miles

|

|

Inn at Podanos

|

to Post at Caena—13 Roman miles

|

|

Post at Caena

|

to City at Faustinopolis 12 Roman miles

|

From Tarsus to Faustinopolis, then, was 62 Roman miles. But in between, as the chart shows, were several inns and posts. A traveler would normally spend the night at an inn (mansio). A post (mutatio) was simply a staging-point where animals could be changed.

Thus, a normal day’s journey for those traveling by carriage was from inn, roughly 25 Roman miles or 22 modern miles. Those who walked, as 041Paul did, would have had to extend themselves to cover this distance. It is unlikely that Paul could have maintained such an average for long periods, particularly when the road was hilly.

If Paul says that he was “in hunger and thirst, often without food, in cold and exposure” (2 Corinthians 11:27), it is obvious that on occasion he found himself far from human habitation at nightfall. He may have failed to reach shelter because of weather conditions; an unusually hot day may have sapped his endurance; mountain passes may have been blocked by unseasonably early or late snowfalls; spring floods may have made sections of the road impassable (he claims to have been “in danger from rivers”)(2 Corinthians 11:26); or fierce hailstorms may have forced him to take refuge. The average height of the Anatolian plateau (present day central Turkey) is 3,000 feet above sea-level, but great sections of it rise to double that and extreme variations of temperature are the rule. The mountainous territory through which Paul Passed in northern Greece would have been only marginally better.

Anyone living in the vicinity of a Roman road, and particular near a post or an inn, was subject to requisition by Roman military, as well as civilian officials. Not only could their animals and vehicles be “borrowed” but they themselves could be pressed into service as porters or drivers. In these circumstances, the ordinary traveler did not get much sympathy. So many demands were made upon those who lived near the road that they would not be apt to offer aid gratuitously. Paul, in consequence, could not count on free hospitality. Despite the traditional generosity of the poor to their own kind, he would have had to pay for both food and lodging—which meant that he had to earn money as he traveled.

Fortunately, Paul had a trade that was much in demand among travelers. As a tent-maker he had the skill to make and repair all kinds of leather goods, not just the animal skins used to make tents, Travelers were shod in leather sandals and often wore hooded leather cloaks. They carried water and wine in leather gourds. Animals were attached to carriages and carts by leather harnesses. Sometimes, the wealthy even carried tents in case they were caught in the open at nightfall. Repairing torn pieces of leather or broken stitches no doubt provide Paul with the means to pay his way. Of course, he had no control over when the demand for his services would come. He could be summoned just as he was starting out from the inn in the morning. He could be involved in a breakdown on the road. He could be kept working late at night by a customer anxious to make an early start next day. Worst of all, he could be commandeered by a soldier or official to repair the soldier’s or official’s equipment. For this, he was unlikely to be paid and all such work meant delay— another reason why Paul sometimes found himself 042far from where he planned to be at nightfall.

When Paul made it to an inn, he could not look forward to a night of total repose. The average inn was no more than a courtyard surrounded by rooms. Baggage was piled in the open space where animals were also tethered for the night. The drivers sat around noxious little fires fueled by dried dung, or slept on the ground wrapped in their cloaks.

Those who could afford better rented beds in the rooms. The snorting and stamping of the animals outside was sometimes drowned out by the snores of others who shared the room, anyone of whom might be a thief. Paul’s anxiety that he might lose the tools of his trade was hardly conducive to a sound night’s sleep. And sound sleep was made infinitely more difficult by that perennial occupant of all inns, the bedbug.

The menace posed by the bedbug is graphically— and amusingly—described in a tale from the Acts of John written in the third century A.D. about a journey from Laodicea to Ephesus.4

“On the first evening we arrived at a lonely inn, and while we were trying to find a bed for John we noticed a curious thing. There was one unoccupied and unmade bed, so we spread the cloaks which we were wearing over it, and begged him to lie down on it, while all the rest of us slept on the floor.

“But when John lay down he was troubled by the bugs. They became more and more troublesome to him, and it was already midnight when he said to them in the hearing of us all, ‘I order you, you bugs, to behave yourselves, one and all. You must leave your home for tonight and be quiet in one place, and keep your distance from the servants of God.’ And while we laughed and went on talking, John went to sleep, but we talked quietly and, thanks to him, were not disturbed.

“Now, as day was breaking, I got up first, and Verus and Andronicus with me, and we saw by the door of the room which we had taken an enormous mass of bugs. We were astounded at their great number. All the brethren woke up because of them, but John went on sleeping. When he woke up, we explained to him what we had seen. He sat up in bed, looked at the bugs, and said, ‘Since you have behaved yourselves and listened to my correction, you may go back to your own place.’ When he had said this, and had got up from the bed, the bugs came running from the door towards the bed, climbed up its legs, and disappeared into the joints” (#60–61).

Paul and his traveling companions must have scratched through many a weary night wishing that they had the power to rid themselves of the pest by means of a simple word!

Danger from robbers is another worry Paul mentions in his catalogue of apostolic sufferings in 2 Corinthians 11:26, and indeed robbers were almost as pervasive as bedbugs. Casson describes a commonly held, but erroneous, view of travel conditions in the Roman Empire at the time: “The through routes were policed well enough for the traveller to ride them with relatively little fear of bandits… Wherever he went, he was under the umbrella of a well-organized, efficient legal system.”5 This was true, however, only to the extent that the Emperor was conceived as a universal protector; in many instances, he did not function in that way. Two episodes from Apuleius’s Golden Ass illustrate the real situation. In one, Lucius, still in the form of an ass, has been driven toward a robbers’ hideout in the mountains. In a town on the way, he decides to invoke the name of the emperor, with the following result:

“It suddenly struck me that I could use the way out open to every citizen, and free myself from 044my miseries by invoking the name of the Emperor. It was already daylight, and we were going through a populous town to which a market had attracted a good crowd. In the middle of these groups, all made up of Greeks, I tried to invoke in Greek the august name of Caesar. I got as far as a distinct and powerful ‘O’ but the remainder, the name of Caesar, I could not pronounce. The robbers, not liking the discordant sound of my voice, took it out of my hide” (3:29).

The point is no less clear for being made with sophistication and wit. The poor had no access to the emperor, and could not effectively claim his intervention.

Powerful and influential personalities were in a different situation. Apuleius’s second story concerns a disgraced procurator who was on his way into exile on the island of Zakynthos. The procurator and his escort were spending the night at a small inn at Actium when it was attacked by robbers. The robbers were beaten off by the procurator’s escort, but the procurator’s wife, who had volunteered to go into exile with him, was so incensed that she returned to Rome and asked Caesar to exterminate the brigands. There was a happy ending.

“Caesar decided that the gang of the brigand Hemus should no longer exist, and it immediately disappeared; such is the power of an imperial wish. The whole gang, chased by detachments of soldiers, ended up by being cut to pieces” (7:7).

As these stories reflect, imperial authority was exercised on the personal demand of those with enough clout to reach the emperor, not by any formal institution.

It was difficult, as well, to invoke the protection of lesser officials, since provincial governors had no permanent forces to perform regular police functions. Although they moved around their territories holding judicial sessions at selected towns, and auxiliary bodyguard units could be used to intervene if necessary, the frequency of a provincial governor’s visits to outlying towns depended on the whim of the official. Many were less than conscientious; even those who took their duties seriously made no effort to cover their territories systematically.6

Apuleius gives a picture of the small towns in northern Greece through which Paul passed that makes them sound similar to the frontier towns of the Wild West that had no sheriff. Individuals had no one but themselves to defend their rights; they often took the law into their own hands. According to The Golden Ass, towns were often run by influential families in their own interest. Thus, we find a outpoor man dispossessed with impunity “by a rich and powerful young neighbor, who misused the prestige of his ancestry, was powerful in local politics, and could easily do anything he liked in the town” (9:35). Just before being turned into an ass, Lucius is warned.

“Take care to return early from your dinner. A gang of young idiots, all from the best families, disturb public order. You will see cadavers strewn in the street. And the auxilia of the governor, far away as they are, cannot rid the city of such carnage” (2.18).

The poor were defenseless before such casual brutality. How could they appeal to the governor? And if they ever reached him, would he accept their version of events?

Neighbors could sometimes band together against outsiders. Apuleius tells the story of a group of robbers who sidle into a town and, by cautious questions in the market, discover the house of the town’s moneylender. The moneylender becomes aware of what is going on, however; when the robbers come to his house that night, he is ready. As the chief robber slips his hand through the keyhole in order to pull the bolt, the owner nails it to the door, and runs to the roof to summon help (4:9–11). A similar story is narrated in 4:13–21. Such justice, of course, was highly localized. One could avoid a charge of murder simply by moving to another town (1:19). Runaway slaves were in little danger of being caught (8:15–23). On the other hand, if feelings ran high, thieves were simply executed on the spot (7:13).

Little imagination is needed to appreciate how vulnerable Paul was under such conditions. He was the stranger, the outsider. There was no one to whom he could turn for aid. He had no neighbors or friends, and could be easily victimized in innumerable ways. I think it very likely that this sense of vulnerability is what lies behind his repeated stress on his “weakness” (1 Corinthians 9:22; 2 Corinthians 11:29).

If the towns were chaotic, anarchy ruled in the countryside. Even in the relatively populous region between Athens and Corinth, the section of this road called the Sceironian Rocks was notorious for the number of its highwaymen. Highwaymen, however, were by no means the only “danger in the wilderness” (2 Corinthians 11:26) that Paul experienced.

Another danger sounds rather banal. Not all the Roman roads Paul walked were as well constructed as the famous Via Egnatia, which he took from Neapolis to Philippi and then on to Thessalonica via Amphipolis and Apollonia (Acts 17:1). The Via Egnatia was a via silice strata, paved with hard igneous rock and bordered with raised stones outside of which was an unpaved track for pack animals 045and pedestrians. Most of the other roads in the East were paved only near towns. In the countryside the road was a via glarea strata, an unsealed br gravel road. On these roads, the danger from flying stones thrown up by passing vehicles was a menace the walking traveler had to live with.

Wild animals were another danger. The story of the Golden Ass is set in an area well known to Paul, the area between Beroea and Thessalonica. As recounted by Apuleius, it was to this region that the rich man from Corinth came to collect wild beasts for his gladiatorial show (10:18). Apuleius refers explicitly to bears (4:13; 7:24), wolves (7:22; 8:15) and wild boar (8:4). Travelers in this story are armed with throwing-spears, heavy hunting-spears, bows and clubs (8:16).

Paul could have encountered some of these wild animals. When he was sent off from Beroea “as far as the sea” (Acts 17:14), presumably he went to Pydna, where the harbor may have remained functional, even though the town itself moved inland in the Roman period. As the crow flies, the distance between Beroea and Pydna is 31 miles (50 krns) over mountainous terrain, a habitat of wild animals.

Several segments of Paul’s second missionary journey were by sea. He sailed from Troas to make his first European landfall at Neapolis, the port of Philippi (Acts 16:11). Certainly the return journey from Corinth via Ephesus to Caesarea was also by sea (Acts 18:18–22).

Combining land and sea travel was common in the eastern Mediterranean. At the beginning of the second century A.D., Pliny the Younger wrote to the Emperor Trajan,

“I feel sure, Sir, that you will be interested to hear that I have rounded Cape Malea [the southern tip of Greece] and arrived at Ephesus with my complete staff after being delayed by contrary winds. My intention now is to travel on to my province [Bithynia] panly by coastal boat and partly by carriage. The intense heat prevents my traveling entirely by road, and the prevailing Etesian winds [north winds that blow from July to September] make it impossible to go all the way by sea” (Letters, 10:15, cf. also 10:17).

As an official, Pliny could requisition boats and carriages at will. Paul had to make do with what was available. When he left from Troas, it is likely that he simply took the first boat sailing to Greece, without being too particular about its specific destination. Since it was summer he could be sure of finding a boat. This would not have been true during the rest of the year, however. In winter, the Mediterranean was effectively closed to travel. Luke notes that “The voyage was already dangerous because the Fast [Yom Kippur, celebrated near the autumnal equinox] was already over” (Acts 27:9). And Pliny the Elder advises us that “Spring opens the sea to voyagers.” (Natural History, 2:47). Storms blew regularly in winter; the violence of these winter storms is well documented. Paul’s trip to Rome started so late in the season that one storm he endured lasted nearly three weeks (Acts 27:19, 27). Josephus records a case where a ship sent to sea in winter on an urgent military mission hit three continuous months of storms (Jewish War, 2:200–203). Not unreasonably, the ancients considered sea travel highly risky between March and May and during September and October. Between November and February, however, it was extremely dangerous. We can easily understand why Paul wintered in Malta, rather than continuing his travels, after his shipwreck (Acts 28:11), and why he considered wintering in Corinth (1 Corinthians 16:6).

Storms were not the only reason the seas were usually closed in winter. Sailors plotted a course by the sun and stars, as well as by landmarks. In winter, fog or heavy cloud cover would cut off their navigational guides, easily leading to shipwreck. Therefore, ships usually did not stray far from land. Particularly in a crowded archipelago, sailors preferred to move from one land sighting to another in daylight. Thus, on the run from Troas to Neapolis, Paul’s ship spent the night at Samothrace (Acts 16:11), and on the trip from Troas to Miletus (Acts 20:6–16), the ship made frequent stops—at Assos, at Mitylene, at a place opposite Chios, and finally at Samos. Cicero describes a similar journey in 51 B.C.:

“Even in July sea travel is a complicated business. I got from Athens to Delos in six days. On the 6th we left; Piraeus for Cape Zoster. A contrary wind kept us there on the 7th. On the 8th we reached Kea under pleasant conditions. We had a favorable wind for Gyaros. Thence to Syros, and on to Delos, the end of the voyage, each time more quickly than we would have wished. You know the Rhodian aphracts; nothing rides the sea as badly. So I have no intention of rushing, and do not plan to move from Delos until I can see all of Cape Gyrae [the southern tip of Tinos]” (Ad Atticum, 5:12.1).

The prevailing wind in the sailing season was called the Etesian wind. It blew from the northern quadrant (northwest to northeast), and most 046consistently from the northwest. Thus, any sea journey to the southeast was likely to be a delight. When Agrippa I (10 B.C. to 44 A.D.) was returning to Palestine to take over the tetrarchy of his uncle Philip, the Emperor Caligula advised him not to take the overland route to Syria, but, as quoted by Philo,

“to wait for the Etesian winds and take the short route through Alexandria. He told him that the ships are crack sailing craft and their skippers the most experienced there are; they drive their vessels like race horses on an unswerving course that goes straight as a die” (Philo, In Flaccum, 26—[trans. Casson]).

The ships referred to are the great clippers that brought Egyptian grain to Rome. These were the biggest and best ships of their day. A contemporary description gives their length as 180 feet, their beam as 50 feet, and their depth, from the deck to the bottom of the hold, 44 feet.7 From Rome to Egypt, they ran in ballast at their best point of sailing and could carry several hundred passengers. The journey from Rome to Alexandria lasted 10 to 20 days.

Things were very different on the return trip from Egypt to Rome. The rig of that time did not allow ships to sail close to the wind; their keels were not deep enough and they lacked jibs.8 Thus, they could not retrace their outward route, but were forced north and east toward the southern coast of Asia Minor. They had to remain at anchor when the winds were adverse and make short dashes when conditions turned favorable.

It is obvious why Paul, of his own free will, never took a ship going west. When he traveled from the Middle East to Europe, he always went overland through Asia Minor, thereby avoiding the frustration of being delayed in port by adverse winds. On the return trip, however, he always took a boat. Once the island of Rhodes had been left astern, it was a straight run to the Phoenician coast (Acts 21:1–3). It certainly saved him several weeks of foot slogging.

Pliny the elder argued that “the sea-sickness caused by rolling and pitching are good for many ailments of the head, eyes, and chest” (Natural History, 31:33)! We will never know whether Paul agreed with this assessment.

Paul sailed west only once—to be tried by the emperor (Acts 25:12). The centurion who escorted Paul obviously knew the wind patterns. In the ports of the southern coast of Asia Minor, he looked for a ship going to Rome; in Myra in Lycia, the centurion found a grain carrier (Acts 27:5, 38). Even if we were not told it was an Egyptian grain carrier, we could have deduced as much from the number of passengers, 276 in all (Acts 27:37). Luke graphically describes the difficulties caused by adverse winds (Acts 27:7–8), and the short-lived euphoria produced by a favorable breeze (Acts 27:14).

There were no passenger vessels sailing regular schedules in Paul’s day. Cargo ships took passengers on a space available basis. The procedure is described by Philostratus in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana:

“Turning to Danis, Apollonius said, ‘Do you know of a ship that is sailing for Italy?’ ‘I do,’ he replied, ‘for we are staying at the edge of the sea, and the crew is at our doors, and a ship is being got ready to start, as I gather from the shouts of the crew and the exertions they are making over weighing the anchor!’’ (8:14).

This vignette omits the haggling over the fare with a hard-eyed owner or his representative who was determined to get the maximum the market would bear. Presumably, maximum utilization of equipment was as much a concern then as it is today, but the ship’s departure had to await the coincidence of a favorable wind with favorable omens. Passengers, too, had to wait; they could not afford to go too far away because the vessel might sail at any moment.

Since passengers were nothing more than an incidental benefit to the owner, the ship provided water, but neither food nor services. Passengers were expected to furnish their own provisions, other than water, for the duration of the voyage. They had to cook for themselves, which meant taking turns, after the crew had been fed, at the hearth in the galley. The fire might be doused by a stray wave, or rough conditions might mean the fire had to be extinguished before passengers had finished cooking, since loose live coals could do irreparable damage to a wooden boat in a very short time.

Passengers had to live on deck; there were no cabins on the average coastal vessel. Apart from a little shade thrown by the mainsail, no shelter was provided. The more experienced travelers brought small tents to protect themselves and their provisions. Tents would also be useful when the boat anchored for the night, often at a port where there was no inn. Frequently, the boat anchored in a small cove whose only amenity was a spring of clear water.

If Paul needed companions on the road for the slight degree of security they provided, a friend was equally necessary on board. It would be difficult for one person to carry on board the provisions 047necessary for an extended voyage, and it was imperative to have someone to keep an eye on them. The fact that tents were in use both ashore and on board gave Paul an opportunity to earn at least some of his passage money.

The discomfort of a sea voyage was intensified by fear. Travelers went by ship only when there was no real alternative. In the world in which Paul lived, the sea was considered dangerously alien. Farewells tended to assume that the friend taking the ship might never be seen again. Poems were written to memorialize the solemn departure. For instance, in order to wish Virgil a safe voyage to Athens, Horace composed a poem in which he evoked the invention of a boat with the words, “A heart enclosed in oak and triple-bonded bronze first committed a frail bark to the dangerous deep,” and so the human race “was launched on the forbidden route of sacrilege”(Odes, 1:3.9 and 16). In other words, in this satirical poem, Horace is saying that the ship was first conceived by a sadistic degenerate whose mission was to destroy humanity. Without this fatal discovery Virgil would not be putting his life at risk by sailing to Athens.

Such sentiments were well warranted, for shipwrecks were common. “Three times I have been shipwrecked, a night and a day I have been adrift at sea,” Paul tells us (2 Corinthians 11:25). The graphic description of a shipwreck Luke gives in Acts 27:39–44 is confirmed by other travelers. For example, listen to Dio Chrysostom (40–120 A.D.):

“It chanced that at the close of the summer season I was crossing from Chios with some fishermen in a very small boat, when such a storm arose that we had great difficulty in reaching the Hollows of Euboea in safety. The crew ran their boat up a rough beach under the cliffs, where it was wrecked. [Dio is befriended by a hunter who tells him] ‘These are called the Hollows of Euboea, where a ship is doomed if it is driven ashore, and rarely are any of those aboard saved, unless like you they sail in very light craft’” (Discourses, 7:2–7).

Only the most urgent business justified Dio’s risking 96 miles of open sea between the island of Chios and the wild, indented east coast of Euboea. He survived only because the light fishing boat would be maneuvered through the surf. A larger boat would have been pounded to pieces further out to sea so that few if any survivors would have made it to shore. Conditions may not have been as violent off the Malta coast where the ship carrying Paul to Rome went down, because all managed to make ashore either by swimming or by holding on to loose planks (Acts 27:41–44).

On at least one occasion Paul found himself “adrift on the open sea” (2 Corinthians 11:26), apparently as a result of some other kind of mishap. On the open sea, a smaller boat might be run down by a bigger one or break a plank on a heavy piece of flotsam. The survivors of an accident like this had no means of sending an SOS. Even if they were spotted by another vessel, the limited maneuverability of ancient ships made it difficult to change course to pick them up. Human life was cheap; if it was too difficult or simply too inconvenient to pick up survivors, they would be left where they were. We don’t know whether Paul was rescued by a passing ship or whether a lucky current washed him ashore. In either event, he was lucky to have spent only 24 hours in the water. And he would have been less than human had he not faced his next voyage with increased trepidation.

I have tried to give something of the reality behind Paul’s impassioned words in 2 Corinthians 11:25–27. When we understand this reality, we better understand Paul’s dedication. I suspect our admiration for his perseverance would be even greater if we knew more about how he tried to ensure his security and earn his way.

Some of the areas through which Paul passed are spectacularly beautiful; yet this seems not to have influenced him in any way. On the other hand, his experiences as a lonely traveler almost certainly affected his theology. His pessimistic view of human nature may have been born of the ethos of his age, but it was surely reinforced by what he encountered at the inns and seaports of Greece and Asia Minor. His own poverty forced him to rub shoulders with the most downtrodden and brutalized elements in society. He no doubt felt the impact of the forces that made these elements of society what they were. He himself felt the force of a value system that the poorer elements of society could not escape. His own struggle against the insidious miasma of egocentricity would have sharpened his consciousness of sin and at the same time strengthened his dedication to the salvation of its victims. “Who is weak, and I am not weak? Who is made to fall, and I do not burn with anger?” (2 Corinthians 11:29).

In the Acts of the Apostles, we are told that Paul made three missionary journeys. In almost every introduction to the New Testament I have seen, the author discusses St. Paul’s journeys in terms of places and dates; his concern is to establish the location of the cities Paul visited and to fix the exact time he visited them. But when Paul himself speaks of his travels he emphasizes, not the “where” or the “when,” but the “how.” For instance, in defending himself against attacks on his authority in the church of Corinth, Paul writes: “Three times I have […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Endnotes

See in particular Fergus Millar. “The World of the Golden Ass,” Journal of Roman Studies 71 (1981) pp. 63–75.

J. Murphy-O’Connor, “Pauline Journeys Before the Jerusalem Conference,” Revue Biblique 89 (1982) pp. 71–91. This table is based on the calculations presented in Robert Jewett, A Chronology of Paul’s Life (philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1979). pp. 59–61.

Except for minor modifications, the translation is that of G. C. Stead in E. Hennecke-W. Schneemelcher, New Testament Apocrypha, 2 (London Lutterworth Press, 1965), pp. 243–244.

Cf. G. P. Burton, “Proconsuls, Assizes and Administration of Justice Under the Empire,” Journal of Roman Studies 65 (1975) pp. 92–106.