In the deft hands of Jerusalem artist Yehudit Shadur, simple sheets of paper are cut into intricate designs blending the poetic words and images of the Bible. A leading reviver of the traditional Jewish folk art of paper-cutting, Shadur combines a sensitive understanding of well-known biblical stories, an intimate knowledge of the plants and animals of the Land of Israel, and a formidable artistic talent.

“I try to create the illusion of depth and solid forms,” she says—“to combine two-dimensional decorative elements with symbols and shapes of monumental weight and significance, to create an atmosphere of grandeur and awe befitting the sacred texts. All this I try to do from a simple sheet of paper cut with a pencil-size, snap-off-blade knife.” Shadur’s seemingly fragile paper-cuts are a delightful combination of lace-like intricacy and bold, sweeping areas of negative or positive space.

Her Jerusalem studio is on a narrow, quiet street a short distance from the official residence of Israel’s president, near the imposing sculptural form of the Jerusalem Theater. Old stone houses—each with a distinctive facade—stand close together, partly obscured by cascades of vines and large pine trees. In one of these houses is Shadur’s studio. A gate opens onto a profusion of flowers; a curving stone staircase leads to her apartment. Like many apartment houses in the older sections of Jerusalem, this one was originally built for a single family. Today, the three-story structure has been divided into several apartments, where, a number of families now live on a smaller, but still comfortable scale.

The studio apartment reflects the lives of Yehudit Shadur and her husband Joe, who came to Israel together from the United States in 1950. On the walls, drawings of plants and landscapes of the Negev are reminders of their ten years as young pioneers at Kibbutz Nirim in the western Negev, and their seven years at the College of the Negev near Kibbutz Sde Boker. From Egypt a tapestry, from Turkey an embroidered wool hanging, a fine collection of first-edition Holy Land travel diaries written by Europeans—all recall their trips abroad.

Yehudit Shadur’s small workroom seems spacious because of its high ceilings and tall windows. A drafting table and large, flat files storing completed paper-cuts fill one side of the room; two walls contain shelves of art and history books, including many on paper-cutting.

The art of cutting pictures from paper is almost as old as the production of paper itself. Paper was invented in China about 2,000 years ago. The oldest extant paper-cuts—more than 1,500 years old—were discovered in excavated tombs in northwest China. These paper-cuts probably served as patterns for other materials out of which the shapes could be cut, sawed or sewn. Papermaking spread westward in the wake of conquering armies, reaching Europe through Spain and Turkey during the 11th century.

Not only was cut paper used to transfer patterns to more durable materials, the craft of paper-cutting became a separate art form among many nationalities and ethnic groups from China to Northern Europe. Unique and distinct paper-cut styles—both secular and religious—developed in different places and cultures.

As early as the 14th century in Spain, an essay by Rabbi Shem-Tov ben Yitzhak ben Ardotiel titled “The War of the Pen Against Scissors,” was “written” in cut-out letters. Like other forms of traditional Jewish art, paper-cutting prominently featured calligraphy and the embellishment of scriptural texts. “This is hardly surprising,” Shadur observes, “since the holy scriptures and the voluminous commentaries that make up the Talmud have been the center of life, as well as the basic textbooks in the education of every observant Jew since ancient times. Indeed, the purpose of traditional Jewish art is to adorn, beautify and enhance the Torah and by so doing to express love and devotion to God.” The artist’s work, Shadur suggests, becomes the embodiment of Exodus 15:2, “He is my God, and I will prepare him a glorious habitation.”

The folk tradition of paper-cutting spread among Jews throughout Europe and North Africa. By the 18th century, the art of paper-cutting was established in Poland, the source of most surviving examples of Jewish paper-cuts found in museums and private collections. Jewish paper-cutting reached its zenith in the 19th century, only to be gradually replaced by mechanically made pictures and posters produced by newly available color-printing processes. The art of paper-cutting never quite disappeared, however. Especially during holidays, when decorations were in demand, paper-cutting endured. It is this tradition that Yehudit Shadur continues.

The most richly developed Jewish paper-cut subject is the mizrah, the Hebrew word for “east.” In Europe, east was the direction of Jerusalem, and it is toward Jerusalem that Jews direct their prayers. Paper mizrahs were hung on the east walls of most of the synagogues and homes in 19th-century eastern Europe. Sometimes it was a simple sign featuring the word mizrah, often it was a work of art, embellished with appropriate sayings, symbols and decorative devices. In her mizrahs Shadur often chooses the saying, “From this direction the spirit of life” (mitzad zeh ruach hayim), an acrostic made from the Hebrew word mizrah. Another favorite is the Mishnaic aphorism from the Pirkei Avot, The Ethics of the Fathers, “Be as bold as the leopard and swift as the eagle, fleet as the deer and courageous as the lion to do the will of thy Father in Heaven.” Sometimes all four animals are depicted on a mizrah.

During the two decades since Shadur began to create art in cut paper, her repertoire of themes has grown, but her inspiration has remained the Biblical text and the evocative imagery of the land of Israel.

Shadur made her first paper-cuts in 1966 at the College of the Negev where she was teaching art. The college campus is located two miles south of the small, rugged kibbutz of Sde Boker where David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, lived. With her students, Shadur decorated a large sukkaha built to receive guests coming to celebrate Ben-Gurion’s 80th birthday. The sukkah was decorated with colorful paper-cuts, pictures, greenery, and clusters of ripe grapes and other fruit. For the center of the wall facing Jerusalem (in the Negev this was the north wall), Shadur made a large paper-cut mizrah. The warm response this mizrah received from BenGurion and his guests inspired Shadur to make a series of smaller paper-cuts using traditional motifs, but incorporating her personal approach.

Shadur’s second paper-cut portrayed Jerusalem, a popular folk art motif and the inspiration of much Hebrew literature, but a subject she had never seen in paper-cuts. Since creating her Jerusalem paper-cut, she has returned again and again to this theme (see photo of Jerusalem paper-cut). Shadur explains the magnetism of Jerusalem: “Depicting the walls, gates and towers encompassing palaces and temples, surrounding mountains studded with cypress and olive trees, and all of this beauty hovering under the Shekhina, the Divine Presence, constantly challenges me to search for the ideal representation of the Holy City of Jerusalem.” But her most frequent source of themes is the Bible—especially the Psalms, among them 48, 122 and 137, which glorify Jerusalem and praise the beauty of Zion.

In the years since 1966, Yehudit Shadur has made many more paper-cuts, exploring the endless effects of this seemingly restricted medium. She studied ancient Jewish symbols—the menorah, tree of life, lions, deer, birds, crowns, vines—as well as the calligraphy of Hebrew inscriptions. She expanded her repertoire by adding motifs found on Jewish amulets, seals and early Hebrew prints of the Holy Land. Later, she added architectural forms she observed in Jerusalem’s streets.

In addition to adapting traditional images used in the past by paper-cut artists, Shadur experimented with themes never before represented in paper-cuts. Reading the Bible with the landscape of Israel in mind suggested new images. One of her first non-traditional projects was a series of paper-cuts based on the Song of Songs and the theme of love. At the time she made this series Shadur did not represent the human form in paper-cuts in deference to a strict interpretation of the Second Commandment, which prohibits the making of images. Her dilemma was how to represent human love without the human body?

Shadur turned to the expressive metaphors in the Song of Songs inspired by the flora and fauna of the Holy Land.

“As the apple tree among the trees of the wood,

So is my beloved among the sons.” (2:3)

“Make haste, my beloved, and be thou like to a roe

or to a young hart upon the mountains of spices.” (8:14)

Another verse in the Song of Songs that inspired a paper-cut compares woman, the bearer of life, to a garden spring:

“A fountain of gardens,

a well of living waters

and streams from Lebanon.”(4:15)

Shadur comments about her attraction to water imagery: “Having lived many years in the Negev, the desert area of Israel, the importance of water for sustaining life and for spiritual well-being takes on a special poignancy for me.”

Other books of the Bible have evoked Shadur’s water imagery. Psalms 1:3 describes the good life of the observant believer: “He is like a tree planted by streams of water that yields its fruit in its season and its leaf does not wither.” This passage accompanies a series of paper-cuts inspired by the Psalms in which Shadur depicts arabesque-like waves of water. A verse in Jeremiah also led Shadur to a flowing water theme in a paper-cut. The prophet relates God’s assurance, “For I will satisfy the weary soul, and every languishing soul I will replenish” (31:25). Shadur illustrates this verse with an elegant, tiered fountain because the Hebrew verb “will satisfy” derives from a word root meaning “to quench thirst.”

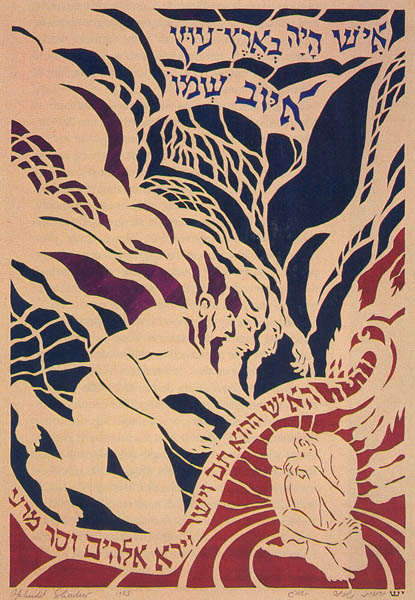

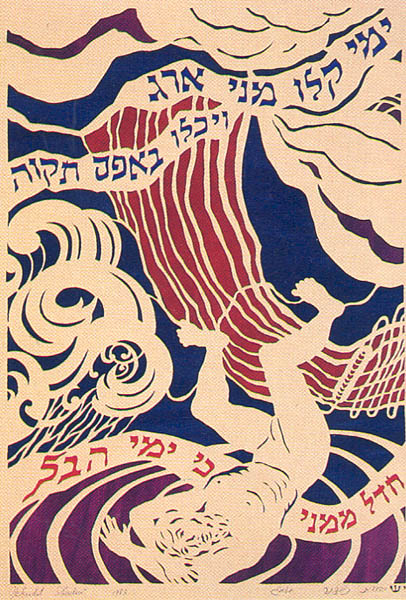

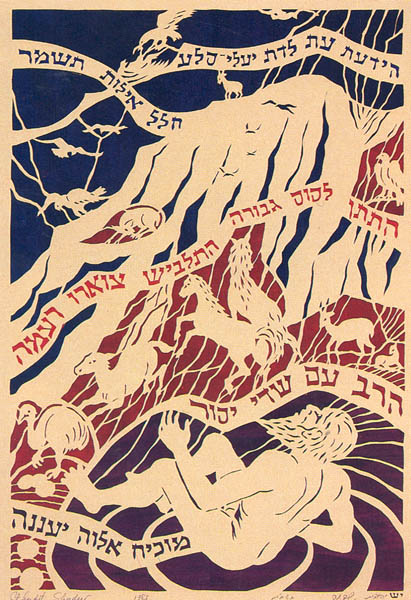

Recently Shadur turned to the subject of Job. Traditional symbols were inadequate to express Job’s anguished quest to understand God. To harmonize the concept of a good and just God with seemingly undeserved suffering and to combine this with powerful nature imagery called for a new approach. Discarding symmetry, and for the first time utilizing the human form, Shadur developed the Job theme in a series of five panels, which we illustrate in the second sidebar to this article. Each panel portrays Job exclaiming a text that Shadur has cut into the composition.

In Job, as with the Song of Songs, the Psalms and the prophetic books, Shadur uses simple materials and tools—paper and pencil-knife—to interpret and embellish a biblical text.