Frank Moore Cross—An Interview

Part II: The Development of Israelite Religion

018

In the August 1992 BR we published the first part of a three-part interview with the world-renowned scholar Frank Moore Cross (see Frank Moore Cross—An Interview, BR 08:04). The interview, conducted in Cross’s home in Lexington, Massachusetts, occurred on the occasion of his retirement as Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Other Oriental Languages at Harvard University.

In the first installment, Cross and BR editor Hershel Shanks discussed the origins of the ancient Israelites, especially Cross’s view that an important component of the Israelites came from Midian (in what is today northwest Saudi Arabia and the southern Jordan) Pointing to a dearth of archaeological evidence for the Exodus in the Sinai, Cross outlined his belief that whatever Exodus from Egypt actually occurred likely went through Midian. Cross also elaborated on the theory regarding the various strands that make up the Bible and on his attempts to study the oldest sections of the Bible to recover the religious thought of the earliest Israelites. It is at that point that we rejoin the conversation.

HS: You spoke of utilizing archaic poetry in the Bible to ferret out the history of Israelite religion and society. How do you tell what is archaic and old, and what isn’t?

FMC: One of the first two monographs that Noel Freedman and I wrote was on just this subject.1 In the book we attempted to isolate archaic poetry by utilizing a series of typologies. Typological sequences are used to date scripts, pots, grammatical usages, prosodic canons and rhetorical devices, spelling practices, art forms and musical styles, architecture, dress fashions, armor and automobiles. The typologies we used in the analysis of archaic poetry included dating linguistic usage, vocabulary, morphology (notably of the verb system and pronominal elements and particles), syntax, spelling styles (a precarious task since spelling was usually revised over the centuries of scribal transmission), prosodic styles and canons, and finally mythological and religious traits. Extra-biblical Canaanite and Hebrew inscriptions have provided the basis for a typological description of Hebrew poetry in the Bible, controlling the more subjective procedure of analyzing biblical literature and developing its typologies only on the basis of internal evidence. Poetry particularly lends itself to this procedure because its metrical structure and set formulas resist in some measure the pressures to modernize that shaped less structured prose.

More subjective, but no less important, is the 019historical typology of ideas, particularly religious ideas. In archaic biblical poetry one finds survivals of raw mythology. In Psalm 29, a lightly revised Ba’al hymn, Yahweh is celebrated as the storm god whose voice is the thunder and whose bolts shatter the cedars of Lebanon. His roar “makes [Mt.] Lebanon to dance like a young bull, [Mt.] Sirion like a young buffalo” (Psalm 29:6). Archaic poetry delights in recounting the theophany (or visible manifestation) of the storm god as the Divine Warrior who marches out to war or who returns in victory to his temple (or mountain abode). In the oracles of rhapsodist prophets—such as Isaiah or Jeremiah—this language comes to be regarded as uncouth if not dangerous and is characteristically replaced in revelations by word, audition or vision of the heavenly council of Yahweh. Instead of thunder we get the word, the judgment.

HS: The still, small voice.

FMC: Just so. The still, small voice is a genuine oxymoron. The Hebrew should be translated “a silent sound.” And the meaning is that Yahweh, whose theophanic appearance Elijah sought, passed with no perceptible noise.

HS: As opposed to passing in the storm.

FMC: Yes. Yahweh passed silently, but happily engaged in conversation with Elijah. The account in 1 Kings 19 (see the first sidebar to this article) of Elijah’s pilgrimage to Mt. Sinai (to escape from the wrath of Jezebel) is most interesting one. It comes at the climax of a battle in which Yahwism seemed about to be 020overcome by Ba’alism, that is, by the sophisticated polytheism of the Phoenician court. Elijah goes to the mountain, to the very cave from which Moses glimpsed the back of Yahweh as he passed reciting his (Yahweh’s) names. Elijah is portrayed as a new Moses seeking a repetition of the old revelation to Moses on Sinai, but one marked by storm, earthquake and fire—in short, by the language of the storm theophany, the characteristic manifestation of Ba’al. In 1 Kings 19 there is wind and earthquake and fire, but the narrative in vivid repeated phrases, tells us that Yahweh is not in the storm, Yahweh is not in the earthquake, Yahweh is not in the fire. He passes imperceptibly, and then speaks a word to Elijah, giving him a new vocation.

In the prophetic literature from the ninth century B.C.E.a to the Babylonian Exile in the sixth century B.C.E., the language of revelation utilizing the imagery of the storm is rare or missing. It does return in baroque form in what I call proto-Apocalyptic (I prefer that label to so-called Late Prophecy). See, for example, the vision of the storm chariot that introduces the Book of Ezekiel. The storm theophany is essentially the mode of revelation of Ba’al. By contrast the mode of revelation of ‘El is the word, the decree of the Divine Council.2 In the virile, unchallenged vigor of early Yahwism, the borrowing of the language of the storm theophany was acceptable. In the era of the prophets the language of ‘El was deemed safer. I suspect that the ancient Israelite may have said simply—in our terms—that Yahweh decided to change his normative mode of self-disclosure.

HS: You have mentioned that there must have been some conflict in the course of the Israelite settlement in the hill country of Canaan. There is much talk these days about the historical reliability or lack thereof, of the conquest stories such as Jericho and Ai. How do these fit into your theory?

FMC: In the case of Jericho and Ai (the name 021means the ruin), there was no occupation in period of the conquest/settlement. There may have been some squatters at one or both sites, but the great, fortified cities did not exist, only their ruins. There are also problems in Transjordan. Heshbon, capital of one of the Amorite kingdoms destroyed by Israel (according to biblical tradition), seems to have been founded after the entry of Israel into their land. We generally date this entrance to the time of Ramesses II (1279–1212 B.C.E.) or the time of Merneptah (1212–1202 B.C.E.). New ceramic evidence for the date of collared-rim jars—a marker of the early Israelites—suggests a date no later than Ramesses II for the beginning of the settlement.3

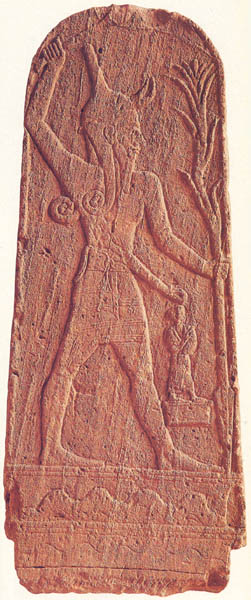

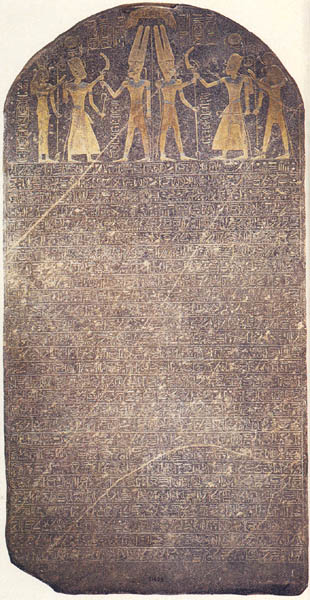

HS: The Merneptah Stele dates to 1207 B.C.E.

FMC: Yes, to the fifth year of Merneptah.

HS: At that time, Israel was already in the land, settled, according to the Merneptah Stele. What you do with that? In this stele, the most powerful man in the world, the pharaoh, not only knows about this people Israel in the land—this is not some commercial document concerning some Israelite about whom we have no information, whether he is a single individual or a member of a marginal tribe or whatever. This people Israel has come to the attention of pharaoh himself. And pharaoh claims that his victory over this people Israel in Canaan is one of the most significant accomplishments in his reign.

FMC: I am not sure I would call Merneptah the most powerful man in the world in this time. Surely Tukulti-Ninurta I of the Middle Assyrian empire, the conqueror of Babylon, the first Assyrian king to add the title “king of Babylon” to his titulary, has a better claim. But never mind. The Merneptah Stele is important, but it needs to be read with a critical perspective.4 Most of the stele contains hymns, or strophes of a long hymn, about the defeat of various groups of Libyans. The final hymn, or strophe, in which Israel is named, describes Merneptah’s conquests ranging from Hatti (the Hittite empire), Libya and the Sea Peoples to Canaan. Then there are claims at the end of the hymn “that every single land is pacified, everyone who roams about is subdued,” justifying John Wilson’s remark that the text is a “poetic eulogy of a universally victorious pharaoh.” The stele is written in parallelistic poetry. Israel is found in the quatrain:

“Ashkelon has been carried off;

Gezer has been seized;

Yano‘am has been made into nothing,

Israel is laid waste; his seed is not.”

Around this quatrain, in an envelope or circle construction, are the lines:

“Plundered is the [land] of Canaan …

Palestine (Hurru) has become a widow for Egypt.”

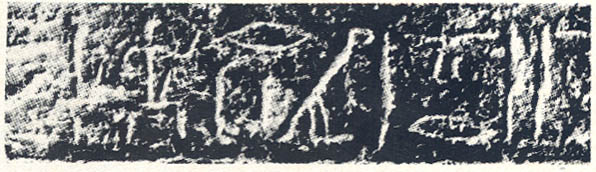

Interestingly, one name for Canaan is male; other one (Hurru) is female. This was no doubt a 022conscious device of the poet. Israel, marked in Egyptian with the determinative sign for the name of a people, not of a place or a state, is in parallel to Ashkelon and Gezer, and more closely to Yano‘am, all three of which are marked with the determinative for city-states. This suggests the scale of importance given to Israel. Further, the pharaoh Merneptah added to his official titulary the title “Seizer of Gezer,” suggesting strongly that of the list of entities in Canaan, Gezer was preeminent. I would conclude that the “Israel” of the stele was a small people, perhaps villagers or pastoralists living in the central hill country, but not the full, 12-tribe league of greater Canaan. The stele, moreover, says that he left Israel destroyed without seed.

HS: Obviously that is wrong. But Israel must have been in the land. That’s 1207, the end of the 13th century. That is before Iron I, is it not?

FMC: Yes to all points. The beginning of the Iron Age we label with a round number, 1200, but we might add: plus or minus a decade or so. But to address your main point, when we say that Israel was in the land, what do we mean? Jacob/Israel is, of course, the eponymous ancestor chosen to head the genealogies of the tribes. But it is not obvious, or even 023credible to me, given the language of the stele, to suppose that the “Israel” of the stele is identical with the Israelite confederacy as it developed in the late 12th and the 11th centuries. The proper name of the early league was the actually the Kindred of Yahweh (‘am yahweh). In my judgment, the first reference to the full confederacy is in the late 12th century (in the Song of Deborah, Judges 5).

HS: What was the Israel mentioned in the Merneptah stele?

FMC: I cannot answer satisfactorily—elements of later Israel.

HS: A particular tribe?

FMC: Perhaps a group of tribes or clans, perhaps—to speculate further—a group in the area of Shechem, about which we have very early cultic traditions going back into the 12th century.

HS: And they were somehow related to the people who later became the 12-tribe league?

FMC: I should think so. But I am not sure that this Israel and the Midianite-Moses group which so strongly shaped early Israelite religionb were yet united. At present I do not think there is sufficient data to decide such questions.

HS: We don’t really know that there was ever a 12-tribe league, do we?

FMC: I am among those who think there was a 12-tribe league. Twelve was a round number and there is documentation of 12-tribe leagues both in Greece and in the south of Syria-Palestine. You could always arrange your tribes and clans so as to come out with 12.

HS: By jiggling the numbers?

FMC: Yes. Is Levi one of the 12? And what of the half-tribes of Manasseh and Ephraim (Joseph’s sons), rather than Joseph? The number 12 also seems to have marked the leagues of Ishmael, Edom and Seir (Genesis 25:13–16, 36:10–19, 36:20–30, respectively).

HS: Would you agree with me if I suggest that the Merneptah Stele seems to indicate that there was an Israel in Canaan perhaps as early as 1250?

FMC: Pottery usually associated with the early elements of Israel perhaps begins as early as the second half of the 13th century. But the Merneptah Stele tells us only that by 1207, a group of people—settled in villages or nomadic, but not constituting a state—called Israel was defeated.

HS: Are you so sure of the dates that you can say that the villages that sprang up in the central hill country of Canaan didn’t appear until after the Merneptah Stele?

FMC: One is never certain within a generation of pottery dates. There is now some evidence for collared-rim jars as early as the late 13th century. But most of the evidence for the foundation of these villages is Iron I, the early 12th century, at least in the view of ceramic specialists (of which I am not one). I have dated one inscription on a collared-rim jar to the late 13th century, but with the recent lowering of the Egyptian chronology, my date too must be lowered, to about 1200 or to the early 12th century. My dating of this inscription was based purely on paleographic grounds; at the time, I am embarrassed to say, I was innocent of the knowledge that the handle on which the inscription was scratched was from a collared-rim jar.5

HS: I see a problem here. The Merneptah Stele indicates the emergence of a people named Israel. It had to have developed before Merneptah heard about these people and was concerned about them 024and wanted to brag about defeating them. So I say that Israel was in the land sometime, conservatively, around 1230 B.C.E.

FMC: I cannot disprove that, but I can continue to ask what size was the Israel of the stele, and what its relation was to the later 12-tribe league.

HS: Then if you say that these villages in the hill country did not spring up until 1180 or so, there is a gap.

FMC: Not necessarily. I have said, basing my views on such studies as those of Stager and Finkelstein, that most of these villages appear to date from the beginning of the Iron Age. Some scenarios can be created to accommodate the data. Let’s say that in the Shechem area, home of ‘Apiru, tribal elements of patriarchal stock consolidated themselves in a covenant of ‘El-berit (El of the Covenant) (Judges 9:46; cf. Joshua 24 and the rites at Shechem). The covenanted clans may have been called by the patriarchal epithet “Jacob /Israel.” One patriarchal cultic aetiology has Jacob/Israel purchasing a plot in Shechem and setting up an altar “to El, the god of Israel [i.e., of Jacob]” (Genesis 33:20). Traditions of the cult of Shechem recorded in the Bible, in which the law was recited and a ceremony of covenant renewal was held at intervals, must have been very early since Shechem was destroyed in the second half of the 12th century. Such an “Israel” may have had nothing to do with other groups of clans coming into the land from the east—e.g., the Moses group, devotees of Yahweh, the ‘El of the south—until sometime later. This Moses group is described as entering Canaan from Reuben and moving into what would be called Judah, by way of Gilgal. Still other groups of tribes in the north, in Gilead and in the far south may have been added (through the mechanism of covenant-making) to the expanding confederation, making up, finally, the 12-tribe league of tradition.

How long such a process would have taken we do not know. How much conflict and warfare was involved as the league pushed out into the uninhabited portions of the central hill country we do not know. We know the expansion was completed by the time of Saul, and I think it highly likely that it was completed by the end of the 12th century. That is, a process that began slowly accelerated rapidly in the course of the 12th century. I am aware that in large part our reconstruction of this era is a skein of speculation. But at least our speculation tries to comprehend all the bits of data we possess at the moment and to interpret them in a parsimonious way.

HS: Let’s go back to Jericho and Ai. You said there were no cities there in the late 13th century, when we would suppose that the conquests had taken place? What do you make of these stories? Is there any history in these stories?

FMC: The conquests of the walled city of Jericho and the great bastion of Ai were not the work of invading Israelites. These cities were destroyed earlier (and at different times). In the account of the fall of Jericho, moreover, there is a great deal of telltale folklore and literary ornamentation. The story of Rahab the harlot is a masterpiece of oral literature (Joshua 2).

HS: But it’s also full of an enormous number of details that fit the location of Jericho, fit the environment, fit the time of year, fit the people—extraordinary details and even a destruction that in the lay mind says okay, maybe the Israelites attributed their victory to some kind of divine cause, but what is preserved here is a real victory that has been elaborated in an epic that attributes a divine cause to a victory that in fact has very natural causes.

FMC: There are two issues here: (1) whether there is any historical reality lying behind the story of the conquest of Jericho, and (2) whether one can explain away divine causes as natural causes. The latter does not really concern us here, though I have never understood why literalists and fundamentalists wish to explain away divine miracles by searching for natural or scientific explanations. To get rid of God in order to preserve the historicity of a folkloristic narrative strikes me as an instance of robbing Peter to pay Paul.

The first question is a more serious one. The details of local color were available to any singer of tales who had visited Jericho. Jericho had undergone a tremendous destruction of an earlier city and lay there in impressive ruins. I am inclined to think that a pre-Israelite epic tradition sang of the destruction, adding marvelous details over time, and that later Israelite singers, composing an epic of Israel’s coming into the land, added the Jericho tale to the complex of oral narratives in their repertoire. Such expansion of epic narrative is characteristic of the process of the creation and transmission of epic, and should not be the occasion of surprise.

HS: Where then do you see the conquest in the Israelite occupation of Canaan?

FMC: There was a great deal of disturbance in this period and the destruction of many sites. It is difficult in any single case to be sure who was the 025agent of destruction. Merneptah and the Sea Peoples were busy in the south and along the coast. Sites in the north like Hazor or Bethel are better candidates for Israelite conquest. But I am inclined rather to credit the consistent witness of early Hebrew poetry that Yahweh led Israel in holy ways and not attempt to trace the conquest in the archaeological record. There are destructions enough to accommodate all parties. As I observed above, the 12-tribe league consolidated itself in the land with extreme rapidity. The speed of the formation of the league would, I think, require military conflict for its success, and military conflict would in turn speed the formation of the league.

HS: We are talking about a couple of hundred years, are we not?

FMC: From Merneptah to the end of the 12th century is a century. By the time of the composition of early biblical poetry in the late 12th and 11th centuries B.C.E., these poets assume a more or less homogeneous religious group, a tribal system with a number of sodalities [brotherhoods or communities]—a league militia a cultic establishment or religious society, priestly and lay leaders.

HS: Let’s turn to the religion of Israel. You have stressed the continuities between Israelite religion and what went before, especially Canaanite and Amorite religion. You have emphasized the relationships and the developments from earlier and contemporaneous West Semitic religion, isn’t that correct?

FMC: I do underline continuities between West Semitic and Israelite religion. This is partly in reaction to a past generation that stressed the novelty and uniqueness of Israelite religion. These claims have now been smothered by a cascade of new evidence, religious texts won by the archaeologist’s spade.

My own philosophy of history maintains that 026there are no severely radical, or sui generis, innovations in human history. There must be continuity or the novel will be unintelligible or unacceptable. This does not, however, mean that nothing new emerges. On the contrary, new elements do emerge, but in continuity with the past.

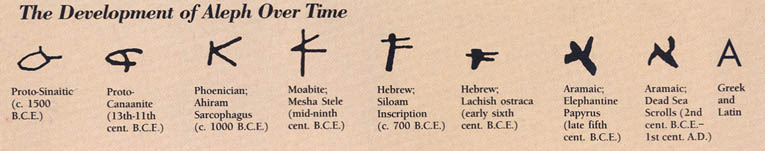

Let me illustrate with an example in paleography. All letters change over time. But their change cannot be so radical as to be unrecognizable. If it is, the writing will be illegible. Change exhibits continuity, but genuinely new styles do emerge. A letter, let us say an aleph, can change from one shape to another over a long period of time, so that one would never recognize the late form as developed from the early. But if the whole typological series is laid out for scrutiny, the continuity from one form to another is continuous and wholly intelligible.

One can speak of revolutions in history or revolutions in religious conceptions and insights. But these great changes are prepared for before they emerge. They may be precipitated swiftly, but if sufficient detail is known, one is able to perceive links and continuity. The new emergent takes up the past into itself.

HS: What is unique and distinct about Israelite religion and how did it emerge?

FMC: Near Eastern religion, and especially West Semitic religion, has at its heart a cycle of myths about the establishment of kingship among the gods. Its cosmogonies and rituals have two levels: (1) the celebration of the victory of the god of fertility and life and order over the unruly old powers of chaos and death, and (2) the establishment of the earthly kingdom after the heavenly model, a ritual attempt to bring the king the nation and its people into harmony with the gods and the state into the eternal orders of creation. This is a profoundly static vision of ideal reality. Such religion is concerned with eternity, not with time or history.

At the heart of biblical religion, on the other hand, is not the imitation of the gods but a celebration of historic events located in ordinary time, events which in theory can be dated, in which historical figures like Moses play a central role. To be sure, in Israelite Epic the hero is a Divine Warrior, Yahweh the god of armies. This is, if you wish, a mythological feature that illuminates history and gives it meaning, direction and a goal. Epic memory and hope gave identity to Israel. Israel’s vocation—a nation of slaves, freed by a historical redemption—was to establish a community of justice. In the new Israel, the ethical was not defined by hierarchical structures in a society established in the created order; we do not find justice as equity according to class. Rather, justice is defined in egalitarian terms; it is redemptive, it frees slaves, uplifts the poor, gives justice to the widow and orphan, loves with an altruistic amity both one’s neighbor (i.e., fellow member of the kinship community) and the resident alien or client (“sojourner” in the King James Version) as oneself. The system of land tenure treats the land as a usufruct [something that can be used by all], a provisional loan from the Divine Landlord, and its largess is to be distributed with a free hand to all in need. Rent and interest and the alienation of the land was prohibited—at least in the ideal law codes preserved by Deuteronomistic and Priestly circles in Israel. The religious obligation laid on the 027Israelite is “to do justice and love mercy” (Micah 6:8) in the here and now, not to be preoccupied with ritual and sacrifice or intent on bargaining with the deity for an individual, eternal salvation. According to its prophetic teaching, Israel was to construct a community of social responsibility, of justice, of compassion and of brotherhood.

This understanding of the business of religion—at least in its emphasis—contrasts with religions that sanctify an order of divine and human kingship. In one sense, Israel’s emergent faith seeks the secularization of religion. For the prophet, neither the person of the king, nor the Temple in Jerusalem, nor any other institution of society is divine or sacral in more than a provisional way, and the survival of these institutions depends on their fulfillment of the command to “Let justice well up as waters, Righteousness as a mighty stream” (Amos 5:24).c

Israel’s religion is historical. It offers no escape from history, but rather plunges the community into the midst of the historic.

HS: You don’t mention ethical monotheism.

FMC: I have been talking about the ethical, and of history as the realm of the ethical. What interests me is Israel’s peculiar understanding of the ethical. Monotheism also emerged in Israel, of course, as it did elsewhere. Once again, I am more interested in the specific type of monotheism found in the Bible than in monotheism as an abstract category. If we define monotheism as a theoretical or philosophic affirmation that “no more than one god exists,” we have not recognized, I think, what is most important about Israel’s concept of their deity. Why is one god better than two or none? The biblical view of God is not abstract or ontological; it is existential. What is important is the relation of the worshiper and the community to its God—obedience to and love of God, rather than affirmation of his sole existence.

The Shema (found in Deuteronomy 6) is often misunderstood as such an abstract affirmation of the existence of one God. It is usually translated: “Hear O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is one.” Literally translated, it reads, “Hear O Israel: Yahweh is our God, Yahweh alone.” The substitution of “the Lord” for the personal name of the Israelite God (Yahweh) confuses matters. To translate “the Lord is one” makes sense as an affirmation of a monotheistic faith. But to translate literally “Yahweh is one” makes no sense. Who would claim that more than one Yahweh existed? Israel was required to worship only one God and to confess his unique and universal power in the historical realm. At least in early Israel, Israelite religion did not systematically deny the existence of other gods or divine powers. In Psalm 82, Yahweh stands up in the council of the gods and decrees the death of the gods because of their failure to judge their peoples justly, and then Yahweh takes over. One may argue that the psalm at once admits to the existence of other gods and asserts that Yahweh killed them off—instant monotheism. I prefer to speak of existential monotheism in defining Israel’s credo.

HS: What you are describing may be henotheism.

FMC: Well, henotheism historically has been used 028to refer to the belief in one local god who enjoys domination over his local turf: Israel or Moab or Ammon. One god per country, so to speak. I don’t think that Israel ever had such a belief, and indeed, even in pre-Israelite Canaanite mythology, the great gods were universal. The myths speak of the land or mount of heritage of some of the gods, but these are favorite abodes and the expressions indicate no limits on their power or, normally, their ability to travel over the cosmos.6

Monolatry is another term that many scholars use: the worship of only one god. This term, also, I regard as too restrictive in defining Israelite faith and practice. In Israel, Yahweh was creator and judge in the divine court. Other divine beings existed, but they were not important; they exercised little authority or initiative. If they retained some modicum of power, let’s say to heal or provide omens, the Israelite was forbidden to make use of their power. Quite early, magic was proscribed. The existence and effectiveness of magic was not denied or theoretically repudiated, but an Israelite was not to touch it. Indeed, there is a law requiring that a sorceress or witch be put to death (Exodus 22:18). Nor is the transcendent one, the God of Israel, to be manipulated.

In short, Israel defined its God and its relation to that God in existential, relational terms. They did not, until quite late, approach the question of the one God in an abstract, philosophic way. If I had to choose between the two ways of approaching the deity, I should prefer the existential, relational way to the abstract, philosophical way. I think it is truer—or, in any case, less misleading—to say that God is 029an old Jew with a white beard whom I love than to say that God is the ground of being and meaning, or to say that God is a name denoting the ultimate mystery. I prefer the bold, primitive colors of the biblical way of describing God.7

HS: You have said that “in Israel, myth and history always stood in strong tension, myth serving primarily to give a cosmic dimension, transcendent meaning to the historical, rarely functioning to dissolve history.”

FMC: I don’t remember that precise quotation but it sounds like me. Let me quote a better statement from the Preface to Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic:

“Characteristic of the religion of Israel is a perennial and un-relaxed tension between the mythic and the historical…. Israel’s religion emerged from a mythopoeic past under the impact of certain historical experiences which stimulated the creation of an epic cycle and its associated covenant rites of the early time. Thus epic, rather than the Canaanite cosmogonic myth, was featured in the ritual drama of the old Israelite cultus. At the same time the epic events and their interpretation were shaped strongly by inherited mythic patterns and language, so that they gained a vertical dimension in addition to their horizontal, historical stance. In this tension between mythic and historical elements the meaning of Israel’s history became transparent.”

Let me illustrate with something concrete—the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15. This poem recounts a divine victory at the sea. Then the Divine Warrior marches with his chosen people to his mount of inheritance and builds his sanctuary. There he is revealed as king, and the poem ends with the shout, “Let Yahweh reign, Forever and ever.” This sequence of themes is really, in outline, the story of Ba’al’s war with Sea (Yamm): Ba’al defeats Sea, builds his temple as a manifestation of the kingship won in his victory and is declared eternal king. But there are, of course, differences in the biblical poem. Yahweh does not defeat the sea, but creates a storm to drown the Egyptians. The sea is his tool, not his enemy, and his real foes are pharaoh and his chariotry—human, historical foes. One is moved to ask, however, why is the central, defining victory of the deity made to take place at the sea? Why not the victory of the conquest? Why isn’t the gift the Land of Promise, which is the climax of the old epic narrative? Surely it is because the old mythic pattern survives and exercises influence. In Isaiah 51:9–11, the old myth resurfaces, so to speak, in the identification of the victory of Yahweh (or rather Yahweh’s arm, symbol of his strength) in the battle of creation against the sea monster, and at the same time (time becoming fluid in mythic fashion) in the cleaving of a path through the sea for Israel to cross over, and (time again becoming fluid) with the eschatological new way through the desert built for the redeemed of the exile to march to Zion. The mythic garb with which historical events are dressed points to the transcendent meaning of event at the sea and of the march to the land. They are the familiar magnalia dei (wonders of God), the plot of the Israelite epic in new form.

HS: Are they historical in any sense that we understand that term, or do we have to do with a transformation of myth into mythical history?

FMC: Both. Many scholars are inclined to call much of biblical narrative mythology. I think this is misleading. On the other hand, I hesitate to use the term “history.” History in the modern context means a description and interpretation of human events arrived at by a specific scientific method. Among the stipulations of 050this method is agreement to eschew discussion of ultimate causation or meaning, these tasks supposedly being left to the philosopher of history or to the theologian or to the Marxist. You don’t speak of divine acts or victories in writing history. At best, the historian can describe people’s beliefs about such matters. Attribution of events to miracle is disallowed on methodological grounds (not necessarily on philosophic or theological grounds, though frequently the postulates of the method become a negative metaphysics for the practitioner). In short, the historian qua historian must put distance between himself and religious affirmations of Yahweh’s divine direction of history. So to use the term “historical” is misleading in describing the constitutive genre of biblical narrative. Sometimes I use the term “historic” (geschichtlich) rather than “history” (Historie). I prefer to use the term “epic”; this term takes up into itself both the historic and mythic elements in the Hebrew Epic.

HS: Is there a factual core?

FMC: In the case of biblical epic and Greek heroic epic, yes. Included in the epic genre are narrative poems with differing amounts of factual, historical memories. Biblical epic in my view is on the more rather than the less side of the spread of historical elements.

HS: Does the historical side matter?

FMC: Yes. Without a historical core I doubt that the historic nature of Israelite religion with its particular values and ethics would have emerged from its Canaanite environment or, later, would have overcome its mythological rivals and survived to become a foundation of Western culture. Unless we are legitimately able to affirm the essential historical character of biblical religion, our religious tradition will tend to dissolve into ahistorical forms of religion: Docetism, Gnosticism, other-worldliness and kindred heresies.

This, of course, cannot be the reason that we insist on a core of history underlying biblical narrative. Our claims must rest on objective historical analysis. But the issue has important consequences for Christianity and Judaism, and for the Western tradition, especially in a day in which diverse mystical and ahistorical religious lore is in vogue under the misleading label of multiculturalism.

The world of epic, in which there is a mixture of myth and history, is not distant from our experience. An American today often perceives his or her place in history in “epic” categories. There is our familiar Pilgrim epic. We, mostly of lowly birth and status, were freed from the persecution and chains of the Old World and led through the perils of the great ocean to a new land, a land flowing with milk and honey. (Mark Twain, standing on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, was unimpressed and exclaimed that the Lord would never have chosen the land of Canaan as the Holy Land if he had ever seen Lake Tahoe.)

The Mayflower covenant or pact was sealed by a company conscious of its repetition of the Israelite liberation and its covenant at Sinai, and members of the company sang biblical psalms as the new land came into sight.

Two epic traditions have been said to mark much of the better American fiction. There is a dark thread that presents the American experience in terms of a broken covenant. It is expressed variously. We are pictured as fouling and corrupting the pristine Land of Promise. You see this vividly in Faulkner’s novels and in Moby Dick, one of the monuments of American literature, a novel full of biblical symbolism. These writers and others express guilt for the American story in our new land: slaughter of the aborigines, the establishment of slavery, reversion to the class system, reversion to the greed and nationalism of the Old World from which we fled, crimes we swore to eradicate.

There is another thread—ebullient, optimistic, a plot taken from the normative American cowboy story or its ancestor, Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. Americans are the good guys who therefore can shoot straighter, who can redeem the wilderness, who create unlimited wealth, who outrun, outwit and outdo lesser breeds. This epic thread is visible in absurd simplicity in the credo of Ronald Reagan: this is God’s land; we are a city on a hill; Americans are God’s people; the future belongs to us. Only the evil empire hinders our apotheosis.

We know that this epic, which informs our lives, is a mixture of myth and history. Few of us are descendants of the Pilgrims who came early to the new land. But in becoming part of the American community and its self-understanding, we live and relive the experience of the founding fathers, just as I think many (or most) Israelites who came late into the Land of Promise and who never saw Egypt did. In their festivals—and in ours—we regard ourselves as having been freed from the house of bondage and led to the Promised Land.

HS: Even today, in the Passover seder, Jews say that they were personally freed from Egypt.

FMC: Yes. Our history with its trappings of myth gives meaning to past and future. We live in a community of epic memories and expectation. I think that is the way human beings are meant to live and think—which reflects the influence on me of biblical religion.

In the August 1992 BR we published the first part of a three-part interview with the world-renowned scholar Frank Moore Cross (see Frank Moore Cross—An Interview, BR 08:04). The interview, conducted in Cross’s home in Lexington, Massachusetts, occurred on the occasion of his retirement as Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Other Oriental Languages at Harvard University. In the first installment, Cross and BR editor Hershel Shanks discussed the origins of the ancient Israelites, especially Cross’s view that an important component of the Israelites came from Midian (in what is today northwest Saudi Arabia and the southern Jordan) Pointing to […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

B.C.E. (Before the Common Era), used by this author, is the alternate designation corresponding to B.C. often used in scholarly literature.

See the first part of this interview, “Israelite Origins,” BR 08:04.

Note that Amos’ oracle here quoted includes these words about the usual practice of religion: “I hate, I despise your feasts, And I will take no delight in your sacred assemblies. Yea, though you offer me holocausts [burnt offerings] and your meal offerings, I will not accept them; Neither will I regard the communion offerings of your fat beasts. Take away from me the noise of your hymns; And let me not hear the melody of your stringed instruments. But let justice well up as waters …” (Amos 5:21–24).

Endnotes

David Noel Freedman and Frank M. Cross, Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry, Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation Series 21 (Missoula, MT: Society of Biblical Literature, 1975).

A long exposition and documentation of the languages of revelation in the Hebrew Bible can be found in the section “The Storm Theophany in the Bible,” in Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1973), pp. 156–194.

The best treatment of the stele and its implications for Israel’s occupation of the land is, in my opinion, the paper of Lawrence Stager, “Merenptah, Israel and Sea Peoples: New Light on an Old Relief,” Eretz Israel 18 (1985), pp. 56*–64*; see also Frank J. Yurco, “3,200-Year-Old Picture of Israelites Found in Egypt,” BAR 16:05.

See Cross and Freedman, “An Inscribed Jar Handle from Raddana,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 201 (1971), pp. 19–22.

On occasion a god may be restricted to the underworld, or Yamm, deified sea, may be banned from dry ground. But even then, Ba’al is resurrected from the dead (and confinement to the underworld), and the cosmic waters may break out of their bounds in bringing the flood.

The masculine or patriarchal language used in describing God in the Bible gives offense to many. At least one should note, however, that Israel’s deity is without a female counterpart and, in contrast to the gods in central myths of sacral marriage in the ancient Near East, engages in no sexual activity. In reality a god without a spouse is sexless.