The Middle East “peace process”—may it be thy will, O Lord—has raised two thorny archaeological issues. Both have recently been in the news.

The first concerns archaeological finds recovered in territories taken in war and later ceded—or to be ceded—to other sovereigns. The results of 15 years of Israeli excavations in Sinaia will be turned over to Egypt, according to a recent agreement between the two countries. Now Palestinian archaeologists, anticipating a sovereign state or autonomous area in the West Bank and Gaza, are laying claims to the Dead Sea Scrolls, as well as to other finds that originated in those two places.

The second issue concerns the Israeli Antiquities Authority’s Operation Scroll—the recent search near Jericho and Qumran for more scrolls.

Both issues involve the competing claims of patrimony and sovereignty, the rights of cultural heirs versus the rights of modern nation-states that own the land. But, as we shall see, there are other considerations as well.

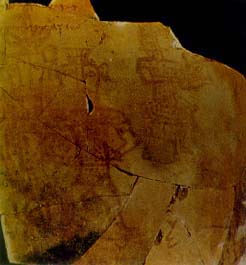

I confess that I start from a not altogether unbiased position. It hurts me that Israel is going to give to Egypt the extraordinary artifacts recovered from Kuntillet Ajrud in Sinai—finds that are enormously important to the study of Israelite religion. Kuntillet Ajrud was a way station or pilgrimage stop for travelers crossing the desert. Archaeologists discovered there two pithoi, or storage jars, with scenes and inscriptions painted on them. The inscriptions refer to Yahweh, the personal name of the Israelite God, and his asherah (or Asherah). Twenty years after their discovery, scholars are still debating whether Asherah, the pagan goddess, was believed by some Israelites to be the consort of Yahweh.b What the pictures on the vessels mean is another fascinating debate. Some scholars believe they depict Yahweh and his consort, but others argue that Yahweh is portrayed in an emptiness. Certain other scenes, such as a line of praying figures, illuminate other aspects of early Israelite religion.

It is not simply that these artifacts should be displayed in Jerusalem. It is that the paintings and inscriptions on these vessels are so fragile, so pale, as to be almost disappearing. They must be treated with extraordinary care or they will vanish. And to the Egyptians, understandably, such artifacts are not important. If displayed in a museum, they will not attract viewers. Where in Egypt will they be stored, under what conditions and for what purpose? Why do the Egyptians want them? How were the Israeli negotiators out-maneuvered?

The Israeli lawyer who advised the Foreign Office in the matter told me the law was clear: Egypt was the sovereign of Sinai; finds recovered from its territory belonged to it. When, a decade or more after concluding a peace agreement with Israel, Egypt asked for them, Israel had no choice.

I don’t believe it. At the very least, Israel could have negotiated for a permanent loan of the Kuntillet Ajrud finds, which mean so much to Israel and little, if anything, to the Egyptians. It would still be a mark of good grace for Egypt to lend these objects to Israel. About the legal aspects of the case, more later.

Some archaeologists are pleased with the agreement to return the Sinai objects to Egypt because the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, allocated two million shekels ($600,000) to support a study of the finds for a two-year period before they must be returned. To rejoice in this, however, is to take a short view of things. That nearly 20 years after they were excavated no excavation report has been published on Kuntillet Ajrud is not quite a tragedy, but it is nothing to be proud of. It is a poor bargain that provides money to study these treasures at the cost of giving them up forever.

Palestinians are now using this case as a precedent for demanding that Israel give up the Dead Sea Scrolls. Qumran, where the scrolls were found, is in the West Bank. The New York Times recently quoted Professor Nazmi Jubeh, a professor of archaeology at Bir Zeit University in Ramallah and technical adviser to the Palestinian delegation to the peace talks: “We want to repeat the Sinai experience. They gave it all to Egypt, so why not to us?” If the Palestinians ever get a Palestinian state that includes Qumran, they will claim that they are entitled to the scrolls, based on the Sinai precedent. The Israeli Foreign Office will make a legal distinction, as one of its lawyers has told me: When Israel occupied Sinai in 1967, Sinai belonged to Egypt; but the West Bank belonged to no one before 1967. Neither Israel nor the rest of the world (except Britain and Pakistan) recognized Jordanian sovereignty over the West Bank and certainly no one recognized it as belonging to a sovereign national entity called Palestine. This argument will appeal more to lawyers than to the media, however.

Yet it is difficult to imagine Israel giving up the Dead Sea Scrolls: They are, after all, Jewish religious documents. But what supports Israel’s claim to the Dead Sea Scrolls? One thing is sheer power—the same reason that the British refuse to give Greece back the Elgin Marbles, and the Turks refuse to return the Siloam Inscription to Jerusalem, and the Germans refuse to return to Egypt the bust of Nefertiti (fraudulently removed from Egypt) and the British Museum refuses to give back to the monks of Mt. Sinai the Codex Sinaiticus (a 4th-century Greek Bible), even though it was only “borrowed” from the monastery, as the monks can easily show.

Yet Israel’s case is based on more than sheer power. The Dead Sea Scrolls are Israel’s patrimony, its cultural heritage.

But does this consideration find any support in international law? According to the Israeli lawyer who advised the Israeli government on the return of the Sinai artifacts to Egypt, the answer is no. I disagree.

Public international law is largely a matter of custom and treaty, rather than judicial precedent. That is because, for the most part, there is no court that renders decisions in suits between nations, issues written opinions on these questions and is able to enforce its judgments.

In recent years, the movement for the “restitution of cultural treasures” has been steadily gaining strength in international legal circles. A number of “returns” have occurred that give standing to a claim for cultural patrimony. A recent study of international law on the subject recognizes that “cultural property is most important to the people who created it or for whom it was created or whose particular identity and history it is bound up with.”1

There are other considerations too. As one noted authority has stated, “Every single object has its own particular history, its own peculiar circumstances of acquisition, and the merits of each case must be weighed. These merits should obviously include such factors as the capacity of the home country to house, protect, study and display any material that is returned, just as much as the gratification of national pride or the soothing of national injury for political or sentimental reasons.”2

These considerations are not exhaustive. In Israel’s case, the issue is not restitution, but Israel’s right to retain the objects against a claim that they be returned. But the considerations are generally the same whether a party is resisting or seeking restitution.

What is clear, however, is that sovereignty over the land where the objects were found is simply one consideration, not a talisman of decision.

Moreover, compromises should be relatively easy to reach. There is enough material to share among the contending parties. What is important to Israel is not very important in the cultural life of Egypt or to the Palestinians or the Jordanians. Another kind of compromise is to give one party title, accompanied by a loan to the other. It should be possible to work these things out.

Problems will remain. Take, for example, the most dramatic finds recovered from Gaza—magnificent anthropoid coffins originally stumbled upon by Gazan farmers at a village named Deir el-Balah.c Eventually, 40 of these coffins were purchased or excavated (illegally) by that romantic eye-patched Israeli general Moshe Dayan. After his death, they were acquired by the Israel Museum. In addition Israeli archaeologist Trude Dothan excavated four more of these extraordinary life-size coffins decorated with sometimes natural and sometimes grotesque faces. Indeed, these faces have Egyptian-like features and come from a period before the rise of ancient Israel. So Israel has less of a claim to these than, say, the Dead Sea Scrolls or the Kuntillet Ajrud pithoi. Yet there is enough here to go around. Why not share them? Why not make the sharing of them a joint project, perhaps rotating museum displays over the years? The possibilities for cooperation are great.

Obviously sites themselves must remain in place. Every sovereign state has an obligation to preserve and maintain sites relating to other cultures. Thus the ancient synagogue near Jericho, with its lovely mosaic floor featuring a Torah ark and a menorah with a Hebrew inscription from the Psalms, Shalom al Yisroel, Peace unto Israel, must remain in place. Whoever controls this area has an obligation to assure that it is properly cared for.

Experience is not always encouraging, however. The Great Mosque of Gaza was originally a Crusader church. One of the upper columns in this magnificent structure had once been a column in an ancient synagogue: Near the top of the column a menorah was engraved. The menorah remained there for all to see from the time of the Crusades to the time of the Intifada. Now the menorah has been destroyed.

In another case from Gaza, a mosaic from an ancient synagogue depicting King David playing a lyre like Orpheus was vandalized. After King David’s face was gouged out, Israeli archaeologists excavated the mosaic and removed it to the Israel Museum, where it has been restored and is now on display (see “King David’s Head from Gaza Synagogue Restored,” in this issue).

On the other hand, one of the most beautiful ancient synagogues, its walls covered with Biblical paintings, was discovered in the 1930s at Dura-Europos, now in Syria. The synagogue has been beautifully conserved and displayed in the Damascus Museum. The Syrian Department of Antiquities has recently supplied us with excellent transparencies of the original paintings from the synagogue as displayed in the museum.

This is perhaps enough to indicate that the issues are complicated and will require Solomonic judgment and creativity to resolve fairly. It remains puzzling why Israel capitulated so simple-mindedly in the case of the Sinai artifacts, particularly regarding the Kuntillet Ajrud finds.

Which brings to us to Operation Scroll. Bottom line: I believe the Israel Antiquities Authority has taken a lot of unjustified flak.

Operation Scroll was an organized effort to explore systematically the caves in the Dead Sea rift in the hope of finding more scrolls. For several weeks in November, some 20 teams that included over 300 archaeologists, volunteers and workers searched hundreds of caves.

Some Palestinian archaeologists accused Israel of raiding the area just before the Israelis were about to leave. For several days, it became a media uproar. Palestinian archaeologist Nazmi Jubeh claimed, “All of these activities are illegal.” Israeli archaeologist Aharon Kempinski echoed this view: A Jerusalem Post article quoted him accusing the IAA of a last-minute “snatch” of antiquities before the area is handed over to the Palestinians.

For the Israel Antiquities Authority, it was damned if you do and damned if you don’t. Once the IAA did a volte-face regarding access to the unpublished Dead Sea Scrolls, following BAS’s publication of a two-volume set of photographs of the unpublished scrolls, attention turned to other scroll issues: how to preserve the fragile fragments, how to remove the cellophane tape that early researchers had used to connect joins, how to save the deteriorating negatives of scroll photographs that had captured many scroll fragments when they were in better condition than they are now, how to get the scrolls studied and published more quickly—and how to search for more scrolls.

The fact is that practically everyone thinks there are more scrolls in the caves. But most of them will be extremely difficult to find. They fall into two categories: In the first category are scrolls in caves whose entrances have collapsed and scrolls that have been buried under the collapse of cave ceilings. The Dead Sea area is prone to earthquakes, lying as it does at the edge of two tectonic plates deep in the Great Rift Valley, the lowest spot on earth. When earthquakes periodically shake the region, boulders, often huge ones, are detached from cave ceilings and pile up on the floors.d Over the years, ceilings and floors both rise. Earthquakes also shut cave entrances, so that even their location is a puzzle. With modern sonar equipment, however, these caves can often be located. To explore caves in this category would require a massive effort, but has the best chance of success.

The second possibility of finding more scrolls is to explore all the accessible caves in the area, even those difficult to enter, and excavate where there is any indication of finding ancient materials. The chances of finding more scrolls in this category are slim. The reason is simple: The Bedouin of the region, many of whom are now experts at excavating caves, have probably found whatever was there and sold it illegally on the antiquities market. Yet, for all their expertise, the Bedouin don’t use the modern methods and equipment (metal detectors, powerful lights, masks, ladders and rappeling gear) of professional archaeologists.

The question becomes: Should we re-explore the accessible caves systematically, just to make sure? The answer seems obvious. We cannot forego the possibility that there may be more scrolls in these caves. Professionals have not really undertaken such a project on a large scale since caves with scrolls were located in the 1950s. Moreover, the longer we wait, the more likely it is that the Bedouin will get there first.

Thus the IAA planned a major exploration of the caves, dubbed Operation Scroll. Not to have done so would also have opened it to criticism. So Amir Drori, the director of the IAA, made the conservative decision: Try to find more scrolls.

Whether there was a “grandstanding” aspect to Operation Scroll, as some critics have charged, is an open question. Doubtless the IAA wished to improve the tarnished image that resulted from its early opposition to free access to the unpublished scrolls.

In any event the project had some bad luck in its timing. Although planned years earlier, it began just after the Great Handshake on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993, looking to a turnover of the Jericho area to the Palestinians. Though it is unlikely that Qumran will be included in this area (the question is still open as I write), Operation Scroll gave the Palestinians an opportunity to make political capital out of the search, and for critics of IAA Director Amir Drori to jump on the bandwagon.

“If you ask me, the chances that they will find something now are one in a hundred,” the New York Times quoted Ya’akov Meshorer, the Israel Museum’s chief curator of archaeology. Whether Meshorer would still take the chance, given the value of the prize, was not discussed in the Times article.

The president of the Association of Israeli Archaeologists, Aharon Kempinski, criticized the quality of the excavations undertaken as part of Operation Scroll, a charge disputed in the box on page 56. Others were critical because the operation failed to uncover any significant scroll materials. But that charge can be made only with the benefit of hindsight. In truth, not much was found: a papyrus fragment from the second century C.E., but this came from a cave that was already being explored and excavated for many years;e a skeleton from the Early Bronze Age buried with some weapons; some flints, coins and pottery; and a pair of Roman period sandals. “The only worthwhile discovery was an ancient pair of sandals. Drori spent a million shekels on an old pair of sandals,” commented another archaeologist, who requested anonymity from the Jerusalem Post reporter.

Drori, a former general in the Israeli army, is a master of terrible public relations. His unwillingness to talk not infrequently gets him into trouble. When one Jerusalem Post reporter tried to interview him, as reported in his article, IAA spokesperson Efrat Orbach “refused to let [the reporter] ‘waste Drori’s time’ with accusations that he’s heard ‘many times before.’” Naturally Drori came off looking bad in the story.

Kempinski called Drori “the Indiana Jones of Israeli archaeology,” charging he was making a media circus out of the event. Drori directed the operation himself from headquarters in a caravan at the settlement of Qumran. However, the temporary quarters were placed in the heart of the ancient Jewish cemetery at the site. When this was called to his attention, Drori simply took down the sign pointing to the cemetery.

The legal question, however, remains: Was it illegal to search the caves for more scrolls? According to the 1954 Hague Convention for the protection of cultural property in the event of war, an occupying power may not remove antiquities. However, it may conduct salvage excavations. The question is whether this excavation can be justified as a salvage excavation, to preserve whatever is found from the depredations of illegal Bedouin diggers. (Would the Hague Convention prevent the removal of the Gaza synagogue mosaic after the head of King David was destroyed?)

To my mind the fact that the search is for Jewish inscriptions known to have been hidden in caves provides additional justification for Operation Scroll, especially because the area may someday be turned over to a population hostile to the recovery and preservation of such precious documents. Whether or not this issue would be recognized under international law, it is a practical aspect of the matter that needs to be considered. The Hague Convention itself speaks of the “preservation of the cultural heritage of a people”; indeed, the entire convention is suffused with this purpose. Surely the Hague Convention, and international law generally, take the purpose of preservation into account in resolving disputes relating to cultural objects.

The resolution of the issues discussed here is complex and uncertain, but fair and reasonable compromises should not be difficult to reach by people of good will.

No doubt our readers will have further light to shed on these questions.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, “Fifteen Years in Sinai,” BAR 10:04.

See the following BAR articles: “Cache of Hebrew and Phoenician Inscriptions Found in the Desert,” BAR 02:01, and André Lemaire, “Who or What Was Yahweh’s Asherah?” BAR 10:06.

See Hershel Shanks, “Excavating Anthropoid Coffins in the Gaza Strip,” BAR 02:01; see also “The Philistines and the Dothans—An Archaeological Romance, Part 2,” BAR 19:05.

For a first-hand description of some of the dramatic finds, including a white-robed skeleton, discovered in caves with collapsed ceilings, see Baruch Safrai, “More Scrolls Lie Buried,” BAR 19:01.

See Esther Eshel, Hanan Eshel and Ada Yardeni, “Rare DSS Text Mentions King Jonathan,” BAR 20:01.