021

In the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 B.C.), Rabbath Ammon was renamed Philadelphia. Despite the name change, the city’s inhabitants remained largely Semitic and probably were never extensively Hellenized.

When Arab Muslims conquered the region of present-day Jordan in 634, they called the city by the name local peoples used: Amman, the modern Arabic version of ancient Ammon. Thus the city became officially Semitic again.

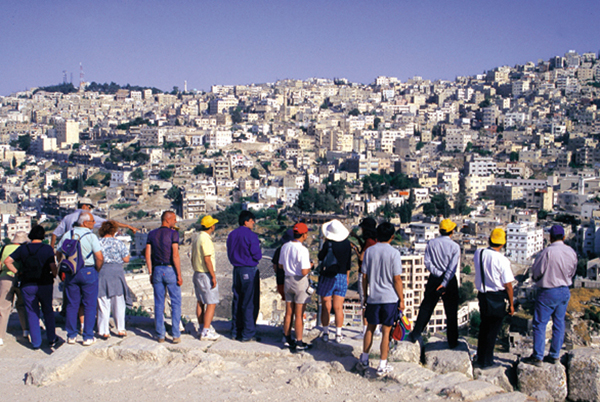

In this, Amman was different from other Levantine cities, such as nearby Jarash or Gadara. The reason is simple. Amman rests among barren rolling hills, cultivable to the west, where the rainfall is higher, but denuded and dry to the east. It is a natural magnet for desert peoples—as Amir (later King) Abdullah realized in 1921 when he decided to locate the Hashemite capital at Amman, where he could rally the tribes of the desert. On the other hand, this site was not particularly attractive to sophisticated Greeks and Romans, who preferred “civilized” places like Antioch or Alexandria.

In the years preceding the creation of the Roman province of Arabia in 106 A.D., Philadelphia was a member of the Decapolis, a league of ten cities stretching between Damascus and Amman. Only a few remains have been uncovered from the Decapolitan period, which does not appear to have been very prosperous. In the early second century, however, Philadelphia began to thrive as a provincial city of the Roman Empire.

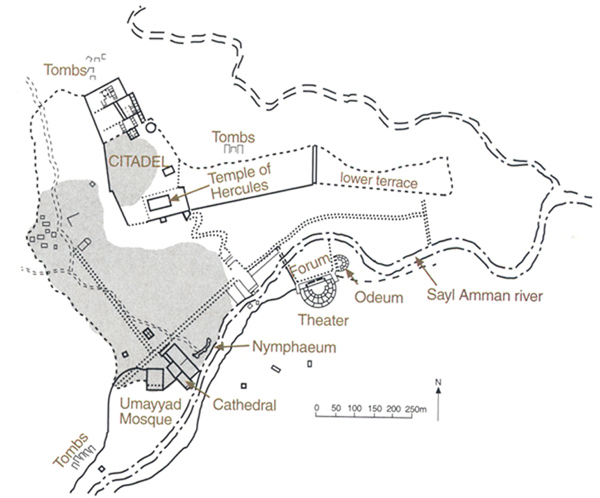

Unlike ancient Rabbath Ammon, the main parts of Roman Philadelphia were not up on the Citadel but down along the Sayl Amman river, which unlike other desert wadis flows throughout the year. A plan of the site was made by the famous British surveyor Claude R. Conder in 1881, just before Circassians fleeing from the Russian advance in the Caucasus resettled in Amman and began to destroy much of what had been preserved from ancient times. Conder’s plan shows a medium-sized town with two colonnaded streets, one running east-west on the north bank of the river (a section of this street, called the Decumanus Maximus, has been revealed in salvage excavations) and the other running northwest-southeast in the valley between Jebel Luweibdeh and Jebel al-Qal’a (the Citadel).

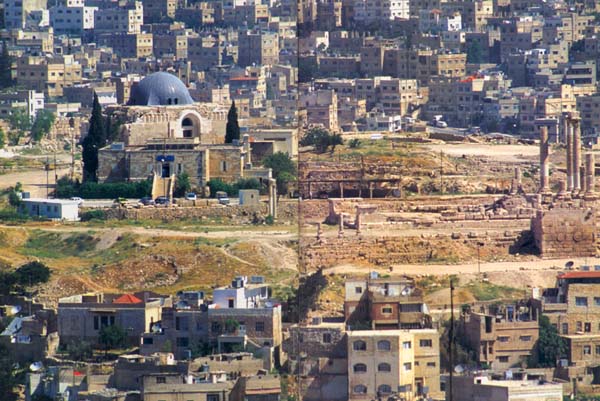

On the south side of the river lay the forum, a large colonnaded plaza dating to year 252 of the Pompeian era (or 189 A.D.). Behind the forum, Philadelphia’s magnificent theater was built into the steep hillside. Probably dating to the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180 A.D.), this theater had 33 rows of seats and accommodated 6,000 spectators. Just east of the forum was the odeum (a smaller enclosed theater), which was 120 feet in diameter. Both the theater and the odeum have now been restored.

Southwest of the forum was Philadelphia’s nymphaeum, a spectacular fountain fed by the Sayl Amman river. It was a half-decagon (half of a ten-sided polygon) about 225 feet long, with three semi-domed apses flanked by two tiers of niches, probably for statuary. The Philadelphia nymphaeum was one of the largest of its kind in the eastern Roman provinces—comparable to, but larger than, 022the splendid nymphaeum of Jerash, which was built in 191 A.D.

On the north side of the Decumanus Maximus, at the foot of the Citadel, was a propylaeon (an entranceway leading to a temple or sacred precinct). Today little remains of this structure, which once probably consisted of an elaborate gateway leading to a stairway rising to the upper terrace of the Citadel. The reason we have no remains is that Amman, lying near a fault line that runs through the Dead Sea and along the Jordan Valley, is hit by major earthquakes about once a century, the last having occurred in 1927. During earthquakes, buildings at the edge of the Citadel tend to collapse and fall down the steep incline. That, no doubt, was the fate of the propylaeon.

Excavations in the 1970s showed that Byzantine buildings on the Citadel’s upper terrace were constructed right on the bedrock. Since the Byzantine period was not a time of monumental construction, it seems likely that the Citadel was razed during the Roman period, probably in the second century A.D. when so much construction took place. Sadly, this means that we have lost forever much of Rabbath Ammon, the glorious capital of the ancient Ammonites.

The Roman-period Philadelphians enclosed the Citadel’s upper terrace with a new fortification wall. The wall was remodeled in the Umayyad period (661–750 A.D.), however, so we do not know much about the details of the earlier towers and gates. The long stretches of completely new Umayyad wall suggest that sections of the Roman wall had collapsed in an earthquake and slid down the hill.

Inside this wall were two sacred enclosures (temenoi, in Greek), one at the north and one at the south. Philadelphia’s urban planners apparently conceived of a monumental acropolis on the upper terrace of the Citadel resembling the Acropolis in Athens—two large temples standing alone on a fortified hill. From inscriptions, we even know the names of two of the sponsors of the work: Martas and Doseos.

The southern enclosure is usually thought to have contained the Temple of Hercules mentioned in an inscription found on Jebel Luweibdeh, the hill just west of Jebel al-’Qal’a (the Citadel). The stairway from 023the propylaeon at the foot of the Citadel, in the principal part of the Roman-period town, led up the hill to a semicircular gate at the southeastern part of this sacred precinct. Clearly identified on the south and east sides, the southern enclosure was a rectangle 390 feet long and 250 feet wide. All that remains of the temple proper is a portion of its huge podium, 140 feet long and 90 feet wide, along with masonry pieces found in secondary contexts in Muslim-period buildings and parts of the temple’s facade, including pieces of the wall and some columns. Although earlier scholars, such as Princeton archaeologist Howard Crosby Butler (1872–1922), showed the facade as tetrastyle (four-columned) in their reconstruction drawings, the size of the podium indicates that it was actually hexastyle (six-columned). The American Center of Oriental Research in Amman has remounted the surviving columns, which are about 33 feet tall.

The northern enclosure was even more impressive, but the Umayyads later built a palace directly over the site, destroying many details. The large complex, about 400 feet square, was a double courtyard built on an artificial platform that projects from the north end of the terrace. The ashlar masonry of the platform walls survives to a maximum height of 46 feet. In its day, this enclosure must have looked like a smaller version of the platform of Herod’s temple in Jerusalem. Portions of the walls of the southern courtyard (of the northern enclosure) are preserved: Its north wall contained niches and podiums (decorative blocks supporting columns), and its east wall was lined with rooms. Traces of a monumental entrance were found by the Spanish Archaeological Mission underneath the later Umayyad reception hall at the southernmost side of the enclosure. Although archaeologists once thought this enclosure was a forum, we know that such massive platforms were only built for temples. Indeed, there were probably two temples, one in each courtyard, but the structures themselves have disappeared. This complex was probably built earlier than the Temple of Hercules, though both are from Philadelphia’s construction-mad second century A.D.

By the end of the second century, Philadelphia had been completely rebuilt in a classical monumental style and had caught up with rival cities, such as Jerash, which had begun building at an earlier date. It is not known what source of wealth made this construction possible, for the local region has never been rich in agricultural land. Probably it was trade, and Philadelphia was at least in part a “caravan city” like Petra and Palmyra.

The Citadel was apparently badly damaged by an earthquake in 363 A.D. This occurred about 50 years after the emperor Constantine (306–337 A.D.) embraced Christianity and shortly before the emperor Theodosius (379–383 A.D.) closed the pagan temples. After the earthquake, then, little was done to restore the Citadel to its classical form. Instead, it soon became the site of Philadelphia’s Byzantine quarter. A Byzantine church on the upper terrace was first excavated in 1938 by an Italian team; and a church on the lower terrace was excavated in 1987 by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities in association with the American Center of Oriental Research. The former was a basilica oriented northeast, with mosaic floors forming an abstract design of overlapping circles. Jordanian archaeologist Fawzi Zayadine dated the basilica to the fifth century, but it clearly remained in use into the eighth century, when it was probably covered over by the Umayyad reconstruction of the Citadel.

The principal church of Philadelphia, located in the lower city near the nymphaeum, was a basilica about 140 by 75 feet. In a photograph taken in 1867, the apse is shown preserved up to three courses of the semi-dome, which was flanked by pairs of arched niches in two tiers. All traces of the church seem to have disappeared during the rebuilding of Amman 027at the end of the 19th century. Historians call this church the city’s cathedral, because it was almost certainly the seat of the Bishops of Philadelphia, who are attested from the time of the 325 A.D. Council of Nicaea. (The Eastern Church still has a Bishop of Philadelphia and Petra.) A Byzantine inscription found in a small chapel built outside a rock-cut tomb on Jebel Luweibdeh, on the grounds of the modern Greek Catholic church, mentions a bishop named Polyeuctus.

Jordan was the first area targeted by Muslim raids after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632. With the establishment of the Umayyad caliphate in 661 A.D., centered at Damascus, the edge of the Jordanian desert apparently became attractive to royal families. The magnificent Umayyad desert castles of the first half of the eighth century, such as Qusayr Amra and Qasr Mshatta, bear witness to Islamic princely luxury. This was the only time in history that Jordan played a significant role in a world empire; the power of the Umayyad caliphate reached from Samarkand in Uzbekistan and southern Pakistan to Spanish Cordoba.

Amman served as an Umayyad provincial capital. One of its Muslim governors, probably a prince of the Umayyad family, rebuilt the Citadel in the 730s. The Citadel of the Umayyad period was an early version of the medieval castle, with accommodation for the prince and his military entourage. The Byzantine quarter of the upper terrace was leveled by simply knocking the upper parts of buildings down into the lower parts. Houses were built for the garrison, and a palace was constructed on the site of the northern Roman-period temenos, following the outer walls of the earlier enclosure.

028

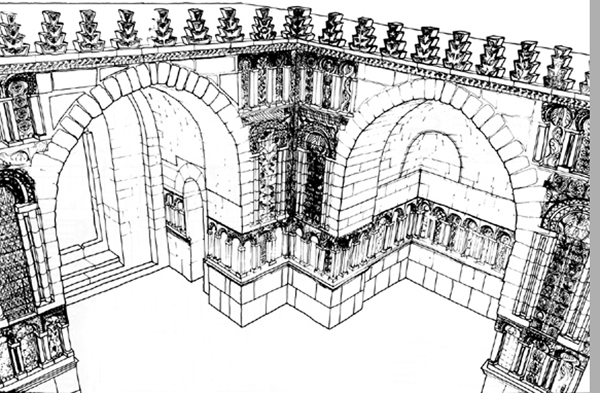

The Umayyad palace was built in the Persian style popular at the time. The reception hall, which dominates the entrance to the enclosure, survives to a height of more than 33 feet. The structure’s exterior is square with barrel-vaulted doorways; the interior is cruciform in shape with two barrel vaults and two semi-domes. The hall’s inner walls are decorated with three tiers of niches carved with Eastern motifs of palmettes, rosettes and trefoils, imitating the sixth-century A.D. Sasanian palace at Ctesiphon, in modern Iraq. In the mid 1990s the Spanish Archaeological Mission, responsible for restoring the reception hall, covered the building with a dome, as would have been done in Spain. Contemporaneous parallels in Iraq and Iran, however, suggest that the center was left open. All in all, the reception hall was a bizarre building, poorly adapted to the cold of the Jordanian winter; indeed, a wooden roof had to be added later as protection from the elements, as we know from holes in the walls of the central court—where supports for the roof were once adjoined to the building.

Inside the enclosure, a short columned street led from the reception hall to a second reception hall at the northernmost part of the complex. This structure had a high open-fronted vaulted hall leading to a domed chamber. On both sides of the street and northern reception hall were buildings used as residential apartments. So far, 13 buildings have been identified.

Recent excavations on the upper terrace south of the Umayyad palace have uncovered a public square with shops. Facing the reception hall from across the square was a sizable mosque, which unfortunately is not very well preserved. On the eastern side of the square a bath has been excavated next to a large circular open-air cistern.

It is an impressive structure—the third largest 029Umayyad palace known, after those at Mshatta and Kuta in Iraq. But there is very little mention of the complex in the chronicles of the period—we only know, from the chronicle of the Arab scholar Tabari (839–923 A.D.), that Sulayman, the son of the caliph Hisham, was imprisoned here in 744.

Soon afterward, in 748 or 749, an earthquake devastated Jerusalem and the Jordan valley. The initial shock was extremely violent and unexpected; at several sites, archaeologists have recovered numerous skeletons of people and animals killed in the collapse. The quake extensively damaged the fortification walls on the Citadel, along with much else. Two houses on the Citadel that were destroyed by the earthquake have been excavated: one in 1949 by G. Lankester Harding, then Jordan’s Director of Antiquities; and the other in 1976 and 1977 by a British team led by Crystal Bennett. These are the earliest well-preserved houses belonging to Muslims. The inhabitants, we learn, used open steatite (soapstone) cooking pots and incense burners imported from Yemen.

Just two years later, the revolution of 750 A.D. replaced the Umayyads with the Abbasid caliphs, who ruled from Baghdad. The new regime had little interest in Jordan, and investment was diverted to Iraq. Amman remained the seat of governors, however, who now arrived from the east, and it was one of the few places repaired after the earthquake.

But this repair did not last long: In the ninth century an earthquake demolished the Citadel’s fortifications and at least one of the palace buildings. This time the Citadel was not repaired; houses were simply built over the remains.

When the Crusaders arrived in 1099, Amman sat on the dividing line between the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Atabeks in Damascus. The city apparently fell into Crusader hands at one point, for two Latin charters of 1161 and 1166 speak of the giving of “Haman” and “Ahamant” as fiefs. Some time after the reconquest of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187, a watchtower was built on the Citadel, but new political arrangements in the Near East had made Amman irrelevant. By the late 14th century the city seems to have been abandoned except as a stop on the hajj road to Mecca. Not until half a millennium later did Amman become relevant once again.

In the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 B.C.), Rabbath Ammon was renamed Philadelphia. Despite the name change, the city’s inhabitants remained largely Semitic and probably were never extensively Hellenized. When Arab Muslims conquered the region of present-day Jordan in 634, they called the city by the name local peoples used: Amman, the modern Arabic version of ancient Ammon. Thus the city became officially Semitic again. In this, Amman was different from other Levantine cities, such as nearby Jarash or Gadara. The reason is simple. Amman rests among barren rolling hills, cultivable to the west, where the rainfall is […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username