One of last year’s most important archaeological discoveries occurred not in the field but in some apartments in Germany. And it was not made by archaeologists but by police after an eight-month sting operation.

Last fall, Munich police raided three apartments during a crackdown on an antiquities smuggling ring. Hidden in the floors and walls of the apartments were dozens of boxes and suitcases stuffed with more than 4,000 ancient artifacts from around the world: East African ceramics, Mayan crafts, Roman coins, Hellenistic pottery and a Coptic prayer shawl from Egypt. But the bulk of the illegal hoard was from Cyprus’s Christian churches and monasteries; the police found more than 140 icons, fragments of Byzantine frescoes depicting Jesus’ disciples, silver crosses, Bibles and prayer books, and exquisitely carved wooden church doors.

On the open market, appraisers say, the icon collection would bring $3 million and the fresco fragments several million dollars apiece; the entire collection may well have a market value as high as $40 million. German authorities removed these valuable objects to the Bayerischer Landesmuseum in Munich.

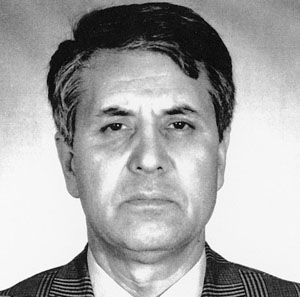

Munich police also arrested the owner of the apartments, a Turkish citizen named Aydin Dikman. Authorities describe the 60-year-old Dikman, who has lived in Germany since 1961, as one of Europe’s most prolific art thieves. Dikman now stands accused of plundering artifacts and works of art from around the world—particularly from Turkish-controlled northern Cyprus, many of whose ancient churches have been systematically robbed of the masterpieces that once graced their sacred interiors. “We have managed to catch the mastermind of the whole smuggling operation,” Athanassios Papageorgiou, a former director of Cyprus’s department of antiquities and an expert in Byzantine art, told Reuters news service.

The churches of northern Cyprus are especially vulnerable to art theft. Since the time of Paul, who visited the island on his first missionary journey (c. 47–49 A.D.), Cyprus has been an important center of Christianity, particularly for the Greek Orthodox Church. In 1572 Ottoman Turks captured the island and held it until the late 19th century, when the Ottoman Empire ceded the island to the British. In 1960 the British handed over control of Cyprus to an unstable Greek-Turkish partnership.

In 1974, Turkish troops invaded Cyprus, which contains a sizable Islamic community of Turkish descent, and seized the northern third of the island. A frenzy of migration followed, with Turkish Cypriots fleeing to the north and Greek Cypriots taking refuge in the south. The island has since been divided between Turkish-occupied Cyprus—which has not been officially recognized by any nation other than Turkey—and Greek-speaking Cyprus.

Over the years, the government of Greek Cyprus has repeatedly accused Turkish forces of permitting, even encouraging, the removal and sale of antiquities from the 500 Greek Orthodox churches now under Turkish control. Although no detailed catalogue of these churches had been compiled before 1974—and official inspections, by such international bodies as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), have not been permitted by Turkish authorities—Greek Cypriot officials report that more than 20,000 artworks and ancient artifacts have been looted from churches in Turkish-occupied Cyprus. Frescoes and mosaics have been ripped from walls and floors, and Bibles, icons, crosses, carvings and chalices have disappeared, according to the Cyprus Weekly.

The shadowy figure now accused of coordinating thefts of numerous artworks from northern Cyprus, Aydin Dikman, has been described in various reports as an archaeologist, an art dealer and a broker dealing in salvageable material from scrapped ships. His name was on a list of suspected antiquities smugglers compiled in the early 1980s, according to the Turkish Cypriot publication Olay. This publication also reported that in 1982 Dikman was detained under suspicion of smuggling by officials of Turkish-controlled Cyprus—a report confirmed by Ahmet Erdengiz, the representative of Turkish-controlled Cyprus in Washington, D.C., who told Archaeology Odyssey that Dikman was released in 1982 because there was insufficient evidence of any crime to arrest him.

Dikman has since been involved in several well-publicized cases involving stolen Cypriot antiquities. In 1983, he and his associates offered to sell 38 Byzantine frescoes to Houston-based art collector Dominique de Menil. Dikman explained to de Menil that the frescoes had been salvaged from a ruin in Turkey, and he invited her to view the paintings at his Munich apartments. De Menil told the Texas Monthly that Dikman struck her as “seedy”; he was very nervous and his apartment was squalid, she said. Feeling that Dikman could not be trusted, de Menil sought assistance from a friend, Herbert Brownell, Jr., a former U.S. Attorney General in the Eisenhower administration. Brownell contacted officials of nine nations situated in what was once the Byzantine Empire and described the frescoes to them. Although Cyprus, Lebanon and Turkey immediately claimed the paintings, the Church of Cyprus produced photographs taken before and after the frescoes were restored prior to the 1974 Turkish invasion—proving that they had once decorated the apse of the 13th-century church of St. Themonianos, near Lysi in northern Cyprus. One of the frescoes was an exquisite depiction of Jesus Christ Pantokrator (shown above)—or ruler of all things—surrounded by angels.

De Menil struck a deal with the Church of Cyprus, which is recognized internationally as the legal owner of Cyprus’s Christian churches and their furnishings: She would “ransom”—to use de Menil’s own word—and restore the St. Themonianos frescoes if the church allowed her to display them for at least 20 years in Houston; after the 20-year period, to begin in 1992, the frescoes would be returned to Cyprus. The church agreed to these terms. The restoration work was completed in 1991 and the frescoes went on display in Houston on February 8, 1997, in the specially designed Byzantine Fresco Chapel.

Despite the fact that these frescoes were illegally plundered from the St. Themonianos church, illegally removed from Cyprus and illegally sold, Dikman was never officially charged with a crime. A member of the legal team representing the Church of Cyprus in a later case told Archaeology Odyssey that Constantine Leventis, then Cyprus’s ambassador to UNESCO and the country’s legal representative in the deal between de Menil and the church, testified that he was unaware of Dikman’s involvement. Cypriot officials apparently decided that they had a better chance of getting the frescoes back promptly and unharmed if de Menil bought and restored them.

This sentiment is shared by Gary Vikan, currently the director of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore. Before approaching de Menil, Dikman had tried to sell the St. Themonianos frescoes for $600,000 to Vikan, who was then a senior associate at the Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies in Washington, D.C. Vikan immediately became suspicious and wanted nothing to do with the deal. But he later observed that had de Menil not bought the frescoes, they would have been acquired by someone else. “I can see someone buying them and putting them in a barn for 50 years,” he told the Texas Monthly. “Or buying them and putting them back together poorly.”

In 1988 Dikman and company struck again. This time they approached an Indianapolis-based art dealer named Peggy Goldberg. They sold her fragments of four rare Byzantine mosaics for more than $1 million. Goldberg then offered to resell the mosaics to the Getty Museum in Malibu, California, for about $20 million; but Getty curator Marion True recognized the fragments as Cypriot and notified Vassos Karageorghis, then director of Cyprus’s department of antiquities. Karageorghis verified that the Church of Cyprus had been searching for these very mosaics: images of Jesus and his disciples that had once adorned the sixth-century church of Kanakaria, near Lythrangomi in northern Cyprus. The government of Cyprus and the Church of Cyprus sued Goldberg in a U.S. federal court in Indianapolis for the mosaics’ return. In August 1989 federal judge James Noland ruled that Goldberg had not made sufficient efforts to determine whether the mosaics had been stolen. The export license for at least one of the mosaics was issued by the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus,” a regime not recognized by any nation other than Turkey, the judge noted. Information about these particular mosaics was even available at the time: The removal of artifacts from the Kanakaria church was reported in a 1977 monograph by A.H.S. Megaw, “The Church of Panyia Kanakaria at Lythrangomi in Cyprus,” as well as at a 1984 museum conference in Athens. Goldberg was ordered to return the mosaics, without compensation for her financial losses, to authorities of Greek Cyprus. Since 1992 they have been on display in the Archbishop Makarios III Foundation Museum in Nicosia.

Once again, however, Dikman escaped prosecution. His luck might have continued had not one of his associates come forward, a flamboyant Dutch art dealer named Michel van Rijn, who claims to be a descendant of the masters Rembrandt and Rubens. Van Rijn told the New York Times that he had helped Dikman sell icons and frescoes plundered from Cypriot churches and monasteries to art dealers around the world. And it was van Rijn, according to Peggy Goldberg’s statement during the 1989 Indianapolis lawsuit, who had set up Goldberg’s initial meeting with Dikman to discuss the Kanakaria mosaics.

After a series of quarrels with Dikman, van Rijn said, he decided to assist authorities in recovering stolen objects he had earlier fenced. Last fall, van Rijn approached Cyprus’s honorary consul in the Hague, Tasoula Georgiou-Hadjitofi, and offered to act as a middleman to help Cyprus buy back artifacts smuggled out of the country under Dikman’s supervision. Cypriot authorities raised $500,000 from various private sources, and van Rijn arranged for the purchase of 32 items from Dikman. Among the objects bought by van Rijn were mosaics depicting Jude (see photo, above) and the doubting apostle Thomas, both from the Kanakaria church; the Jude mosaic may be worth as much as $8.6 million on the open market. Van Rijn also bought several frescoes from the 12th-century monastery of Antiphonitis, located in the mountains of northern Cyprus.

Van Rijn’s bodyguard videotaped these transactions and turned the tapes over to German police, according to the New York Times. In October and November of last year, the police conducted two separate raids on apartments owned by Dikman, finding ancient artifacts and valuable works of art stolen from around the world and smuggled into Germany.

The police also found documents in Dikman’s apartments that detail his methods of pilfering Cyprus’s churches. Photographic albums contained pictures of looters climbing scaffolding and removing fresco fragments from the walls. Notebooks found in the apartments contained drawings of frescos known to have disappeared from churches in Turkish-controlled Cyprus; the drawings are marked with lines showing workers what portions of the frescoes to hack off—directing them particularly to the valuable faces of Jesus’ disciples.

The government of Cyprus immediately claimed two carved doors that Dikman’s henchmen had allegedly removed from the church of Peristerona, six frescoes and 92 icons. Archbishop Chrysostomos, head of the Church of Cyprus, believes that 210 more objects from the Dikman hoard belong to Cyprus and will be returned once the church can prove ownership.

Dikman, who has been charged in Germany with trading in stolen artifacts, faces up to 15 years in jail if convicted. His case is still pending as authorities continue to recover items he allegedly sold to dealers around the world.

But according to Cypriot authorities, these recoveries are only the tip of the iceberg. They claim that important and valuable works of art have been, and are still being, systematically looted from Cyprus’s Christian churches—and that this is the modern equivalent of the Islamic iconoclasm that swept through the Byzantine world in the eighth and ninth centuries, destroying much Christian art. Athanassios Papageorgiou, who currently is preparing an inventory of antiquities in Cyprus’s Orthodox Christian churches—including frescoes, icons, wood carvings, manuscripts, mosaics and old books—estimates that Cyprus once contained more than 200,000 Byzantine artifacts.

The President of Turkish-controlled Cyprus, Rauf R. Denktash, has often denied charges that his government has permitted the plundering of Greek Orthodox churches. The Turkish Cypriot government concedes that some monasteries in northern Cyprus have been violated, but not nearly to the extent reported in the media; it claims that Turkish Cyprus has only limited resources to protect and restore the churches and that foreign nations, which do not recognize the government’s authority, are loath to part with aid money. Moreover, in the northern Cyprus city of Famagusta, the Denktash government has restored the huge Gothic cathedral of St. Nicholas (which had served as a mosque since 1571) and turned the monastery of St. Barnabas into a splendid icon museum.

Nonetheless, artworks from northern Cyprus continue to appear on the market. This February, for instance, German police confirmed that nine icons from northern Cyprus had been recovered from Serafim Dritsoulas, a Munich-based Greek art dealer, who had bought them from Dikman. Papageorgiou believes Dikman is one strand of a large web of smugglers operating out of the Netherlands, Japan, the U.S., Greece and other countries. Cypriot pieces sold by Dikman have passed through Britain, Belgium and Switzerland, suggesting the existence of a network of intermediaries capable of routinely violating the laws of several countries. Some plundered Cypriot treasures, according to Archbishop Chrystomos, are known to be in Britain, waiting to be sold or moved to safer locations.

Although Cypriot authorities know about these and other looted works of art, they often do not have sufficient resources or evidence to take legal action. So they recover what they can, sometimes by “ransom,” hoping someday to restore their churches’ sacred precincts.