Heinrich Schliemann’s second season of excavation in 1872 on the mound of Hisarlik, which he fervently believed to be the site of Homer’s Troy,1 had ended in triumph. He had discovered, so he thought, the “Great Tower of Ilium”—which Hector’s wife Andromache anxiously climbed upon learning that the Trojans were being pushed back by the advancing Greek armies (Iliad, Book VI).

Shortly afterward, however, in February 1873, Frank Calvert, a British expatriate who had initially interested Schliemann in excavating Hisarlik, published an article in the Levant Herald in which he debunked Schliemann’s “Great Tower.”2 Calvert, who had spent most of his life in the Troad, the area around Troy on Turkey’s northeast coast, and who knew more than anyone about its archaeology, correctly observed that the “Great Tower” was not a tower at all but simply the place where two different phases of a city wall parted and reconverged.

Calvert raised anot her point, even more devastating. He argued that the numerous occupation layers Schliemann uncovered essentially represented only two cultures: a Greek-Roman culture that extended down to a depth of about 6 feet, and a much earlier society below that level. In the earlier levels, dating to the Early Bronze Age, stone tools were common, metal tools and weapons were scarce and made of bronze, and finds of gold and silver jewelry were meager. Calvert showed that the lower culture could not be later than 1800 B.C. and the upper not earlier than 700 B.C. Roughly a thousand years were missing between these two cultures.

Modern archaeologists have confirmed that Calvert’s analysis was essentially correct. But if Calvert was right, what Schliemann had excavated could not have had anything to do with the events described by Homer in the Iliad. Everything was either far too early or far too late! Historians have agreed, then as now, that the Trojan War, if historical, must have taken place about 1200 B.C.

Schliemann was enraged by Calvert’s article. Nonetheless, he confidently proceeded with his third season of excavations. He now dug a long east-west trench to meet the enormous north-south trench he had cut through the mound in 1872. These two trenches revealed a complex network of walls in a series of “cities,” or occupation levels, built over one another. His finds, on the other hand, proved rather disappointing. Although he unearthed a huge quantity of unusual pottery that was surely very old, he found little that suggested the grandeur and sophistication of the world of Homer’s heroes.

Not far into the third season, he discovered a number of significant finds in the great east-west trench, including inscriptions and pieces of statuary from the upper (Greek and Roman) levels and about 40 bronze tools and weapons, mostly from the lower (Early Bronze Age) levels. Most of these finds he secretly shipped off to Athens. Then he found what appeared to be the city wall of Troy II—the level he believed to correspond to Homer’s Troy (we now know that this level dates to about 2400 B.C., more than a thousand years earlier than the Late Bronze Age city Homer wrote about). At a break in this wall, near the southwest corner of the mound, he came upon an impressive city gate, which he immediately identified as Homer’s Scaean Gate, and behind that, the walls of a ruined building. Here he also found some remarkable pieces of pottery, including a 2-foot-high, terracotta vase with an owl-like face, a necklace, breasts and a girdle draped over the shoulder. Could this building be King Priam’s palace?

On May 23, 1873, Schliemann made a spectacular find in a room of this “palace”: a large silver vase with a smaller silver vase inside it and some fragments of bronze that he identified as “helmet pieces” (in reality, parts of a bronze vase). A few days later, on May 31, came the discovery that has endured as one of the most famous moments in the history of archaeology. This is how he describes it in the official report:

Behind this [wall] I exposed at a depth of 8 to 9 m. [almost 30 feet] the Trojan circuit-wall as it continues from the Scaean gate, and in excavating further on this wall, right next to the house of Priam, I came across a large copper object of the most remarkable shape, which attracted my attention all the more as I thought I saw gold behind it In order to withdraw the treasure from the greed of my workmen, and to rescue it for science, the utmost speed was necessary, and although it was still not yet breakfast-time, I immediately had “païdos” [a work break] called. While my workmen were eating and resting, I cut out the treasure with a large knife. It was impossible to do this without the most strenuous exertions and the most fearful risk to my life, for the large fortification-wall, which I had to undermine, threatened at every moment to fall down on me. But the sight of so many objects, each one of which is of inestimable value for science, made me foolhardy and I had no thought of danger. The removal of the treasure, however, would have been impossible without the help of my dear wife, who stood always ready to pack in her shawl and carry away the objects I cut out.3

Then follows a detailed description of the individual pieces of “Priam’s Treasure”: four bronze objects, three gold vessels, one gold cup, six silver ingots, three silver vases, one silver cup and one silver dish. But that was only the beginning: He also found 37 bronze weapons or tools, two gold diadems with pendants and one without, 60 gold earrings and 8,750 gold beads. Since all these objects were found tightly packed together, Schliemann thought that they might have once been in a chest. Nearby, he found what he thought was the key to the chest. His vivid imagination conjured up a stirring scene:

It is probable that some member of the family of King Priam hurriedly packed the Treasure into the chest and carried it off without having time to pull out the key; that when he reached the wall, however, the hand of an enemy or the fire overtook him, and he was obliged to abandon the chest.4

Much of Schliemann’s account of the discovery of Priam’s Treasure is fiction, certainly in giving Sophia a leading role. As Schliemann’s own diary and correspondence attest, she was in Athens on the day of the discovery. It is also unlikely that Schliemann got down into the trench and personally removed the treasure. That would have attracted the attention of the Turkish overseer. More likely is the account he gave to a friend on July 5, 1873: “The greatest difficulty I had was to save [the treasure] in the presence of the Turkish watchman, but I succeeded in doing so by suddenly singing out that it was my birthday, by feigning to drink freely and by making my Turk drink copiously of that famous liquor called ‘cognac,’ a word which hereafter I shall never be able to hear without breaking out in shouts of laughter.” This clearly implies that Schliemann distracted the overseer while the workmen removed the treasure from the trench.

As was his practice, Schliemann rewarded the workmen for the pieces they brought to him. Perhaps he did not pay them enough, for later in the day Amin, the Turkish overseer who had been plied with cognac, heard that a valuable find indeed had been made. He rushed into Schliemann’s house and demanded that the chests and cupboards be opened immediately. But Schliemann threw him out. Amin left the site intending to return the next day with gendarmes to force a search of Schliemann’s chests and cupboards. About 7 o’clock that evening, two German visitors arrived unexpectedly, Gustav von Eckenbrecher and his son Themistocles. Gustav later described their arrival at Hisarlik:

We left our horses below and climbed the steep slope over the debris and along narrow paths beside deep excavation trenches. At the top Schliemann came to meet us—a sunburnt, stocky figure of medium build. On his head, which was shaved quite bald, was a straw hat bound all around in Indian fashion with white muslin. His linen paletot coat was covered with the dust of the excavations and his whole face even more so. He asked us if we spoke German. I told him my name and at once we were afforded the most hearty welcome. The larger of the small houses which he had built for himself on Hissarlik was shown to us as our lodgings—for otherwise there would have been no accommodations to be found far and wide—but then he begged us to excuse him for he had pressing business to attend to and could no longer look after us for the present. It was, as we later learned, the evening on which he had to dispatch the “Treasure of Priam” to Athens, which had to be done with the greatest care. His wife, a young Athenian lady, his otherwise constant companion in his Trojan excavations, was not present; she had gone back to Athens.

The stone house where we were now staying, completely surrounded by deep excavation trenches, consisted of a large room, adjoining which there was a kitchen and servant’s quarters. For sleeping, Schliemann had assigned us his own very spacious bed After we had fortified ourselves at the evening meal with fine bread and an authentically Asiatic roast of mutton-tail and excellent Tenedos wine, Schliemann was once again free, and we spent the rest of the beautiful evening sitting in the front door of our house, talking of many things and recalling the events that happened here in remote antiquity. After sunset, the sky and the Hellespont gleamed in the glimmering twilight, the craggy peaks of Imbros and Samothrace were sharply distinguished on the horizon and even distant Athos was visible.

Schliemann seems to have been busy packing the treasure when the Eckenbrechers arrived. As the workers left at sunset, he dispatched the treasure to the farm of Frederick Calvert (Frank’s brother), which was located about four miles south of the site, with the following note:

I am sorry to inform you that I am closely watched and expect that the Turkish watchman who is angry at me, I do not know for what reason, will search my house tomorrow. I therefore take the liberty to deposit with you 6 baskets and a bag begging you will kindly lock them up and not allow by any means the Turks to touch them.

On June 6, 1873, Schliemann had the treasure secretly removed from the farm and smuggled to Athens. He announced his great discovery to the world in August and put Priam’s Treasure on display in his house in Athens, inviting leading Greek and foreign scholars to examine it. A few months later, when the Turkish government started a lawsuit in the Greek courts for its half-share of the treasure, the treasure disappeared again, this time, as we now know, to the French School at Athens.

After a year of legal maneuvering, the Turkish government reached an agreement with Schliemann, whereby it seems to have renounced its claims to a half-share of the treasure in return for a cash settlement of 50,000 francs (according to Schliemann’s correspondence). Unfortunately, the text of the settlement agreement, with the precise terms, has never been published. The relevant documents, if they are ever found, would be of great importance in connection with the current controversies over the treasure’s ownership. After Schliemann settled with the Turkish government, he was able to bring the treasure out of hiding. But he eventually tired of showing it to the endless stream of visitors it attracted to his house. In 1877 he put it on temporary exhibit at the South Kensington (now the Victoria and Albert) Museum in London. In 1881 he transferred it to Berlin, giving it in perpetuity to the German people. In return, he was made an honorary citizen of Berlin.

In 1945, when Soviet armies reached Berlin, they found the Trojan treasures along with other valuable art works in a flak tower (a placement for antiaircraft guns) in the Berlin Zoo, where they had been taken for safekeeping. From there, they were transported to Russia.

Most of the gold and silver pieces of Priam’s Treasure ended up in Moscow, but many bronze (and some silver) pieces went to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. For the next 50 years the treasure lay hidden in museum storehouses, with the Soviet authorities insisting that it had never reached Russia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, reports began to appear that Priam’s Treasure was in storage at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow; in 1994 this was officially confirmed by the Russian government. Since then, the major pieces have been put on public display: Most of the gold and silver items were exhibited in the Pushkin Museum in 1996, and some bronze and silver pieces were exhibited in the Hermitage in 1998.

The first object in the treasure that Schliemann said he removed from the trench is a 20-inch-wide, circular bronze piece, with a raised boss (or omphalos) in the center surrounded by a raised ring. Schliemann incorrectly identified this as a shield. In fact, it is part of a pan, usually called a “frying pan” from its shape. The handle, to which a silver cup was attached, had broken off. Schliemann did not associate the handle with the pan, thinking that the former might be the hasp of the lost treasure chest. Today, the pan is in Moscow and the handle is divided between Berlin and St. Petersburg—a stark reminder of the dislocating effects of war on cultural property. Only a few of these “frying pans” have ever been found, most of them in the Troad. No one knows what they were used for. One scholar has suggested they might have been used for gold-panning, whereas another believes they served some ritual function.

Two other finds, small gold cups, are both elegantly fluted, one with vertical and the other with diagonal ribs. One can readily imagine a Trojan leader of the late third millennium B.C. sipping wine from these beautiful cups, perhaps poured from a spherical gold flask also found by Schliemann.

Unquestionably the finest piece in the treasure is the so-called sauceboat, also made of gold. Though some similar sauceboats with a single spout and a single handle are known in both gold and ceramic, no other two-handled piece quite like this has ever been found in any medium. Its unique shape perhaps suggests a ritual function.

Six silver ingots, now in the Hermitage, if not exactly Homeric “talents,” as Schliemann thought, may well have had a similar function. In pre-monetary societies, precious metals, especially silver, often served as money. The value of the ingots would have been determined by their weight. The weight of three of them is virtually identical, ranging from 5.9 to 6 ounces.

Of the three large silver vases in the treasure, two are without handles. The third and largest vase has one handle. Inside it Schliemann claims to have found the two gold cups and all the jewelry.

Two small silver vases have lugs for suspension and are supplied with lids. In 1890 Schliemann found another vase of this type at Troy, this one in a grave. So this type of vase must have been considered appropriate as a funerary offering.

Schliemann counted 13 “spearheads” (or “lances”) in the treasure. Scholars now identify them as daggers. He also found seven “daggers” now considered spearheads. The treasure also includes 14 axes, which were probably once attached to wooden shafts with leather thongs. Schliemann called them “battle-axes,” but they are now viewed as tools and are referred to as “flat-axes.”

Among the jewelry, the most outstanding pieces are the two gorgeous diadems with pendants. These would have been worn across the brow with the longer side sections framing the face. The famous photograph of Sophia Schliemann wearing the large diadem shows how this could be done. However, because the chains in the brow section are so long (about 4 inches), she had to pile her hair high on top of her head and fasten the top of the diadem across her hair, rather than across her brow, so that it would not cover her eyebrows. For this reason, some have suggested that the diadems were intended not for humans but for larger-than-life cult statues.

Almost as striking are two pairs of basket earrings fitted with chains and pendants. Schliemann found several pairs of these earrings at Troy. Similar, though less skillfully worked, examples have been found at other Anatolian sites, notably at Eskiyapar in central Anatolia and at Poliochni on the island of Lemnos, not far from the Troad.

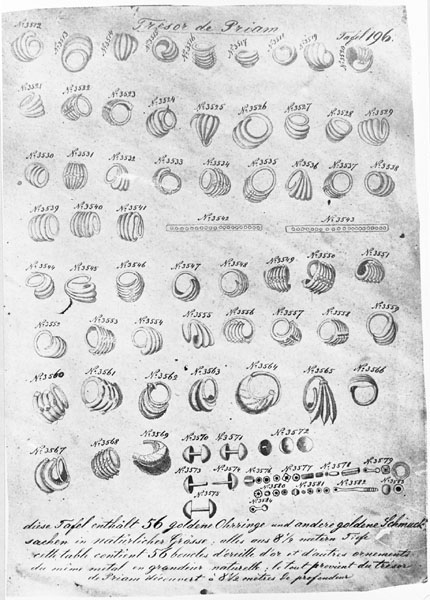

Besides the two pairs of basket earrings, the treasure includes 56 smaller gold earrings (though some scholars believe they were used, instead, as hair-rings). These fall into three groups: 30 plain earrings with three, four or six lobes; 20 earrings decorated with rows of studs; and six earrings with faceted segments and granulation along the ribs. The earrings of the first two groups are fairly ordinary and are found in many Anatolian sites from the late second millennium B.C. But the three pairs of granulated earrings are impressive. Goldsmiths in the 19th century wondered how the prehistoric craftsmen had been able to affix the small granules of gold to the body of the earring—a skill that had been lost for centuries.

Many of the 8,750 beads are intricately worked despite their tiny size, attesting to the skill of the craftsmen some four thousand years ago. Most of these beads would have been strung together to form necklaces. The string joining them has long since disappeared and we can now only guess how they might have been arranged.

While Priam’s Treasure certainly contains some beautiful pieces, a great many others have little aesthetic appeal. Why then is it so famous? Part of the answer lies in the romantic account of its discovery and the extraordinary story of what happened to it since 1873. Schliemann’s long fight with the Turks over ownership brought notoriety to the treasure shortly after its discovery. His attribution of the treasure to Priam, the noble king of the Trojans, has also been a factor in its fame. Despite the false attribution (off by a thousand years), both name and fame have stuck.

Is the treasure archaeologically important? Definitely “yes,” even if that “yes” now needs some qualification.

In the Bronze Age, Troy was an important bridge linking east and west. The rich array of finds it has produced is important not only for what it tells us about the culture of the Trojans, but just as often it is important for what it tells us about other sites. Archaeological sites are not unlike Internet web sites. Ultimately, they are all connected by an intricate series of links. An unusual piece, like the “frying-pan,” immediately links together the small group of sites where this kind of object has been found. The greater the number of links that can be established between sites, the clearer the relationship between them becomes. In this game of connections, a large find comprising many different pieces that can firmly be attributed to a single stratum is of great importance because of its potential for establishing secure links with a large number of other sites. Of particular importance are “closed deposits,” in which all the pieces were laid down at the same time (as, for instance, when someone buries a hoard of valuables in a jar). If a large find can be shown to be a closed deposit, then all the items must be contemporary. Given Schliemann’s report that he found all the pieces packed together in a mass, archaeologists regard Priam’s Treasure as a closed deposit. It is of unusual importance because of the unparalleled range of objects that it contains.

Its status as a closed deposit, however, has recently been challenged. It has been argued that the treasure is rather a composite of a number of smaller finds made over the preceding months. A key element in this argument is the growing mass of evidence that Schliemann told a great many lies. Anthony Snodgrass of Cambridge University has called him “profoundly dishonest.”5 Contrary to what his supporters have maintained, this penchant for deceit has also contaminated his archaeological reporting. Casting Sophia as the sole witness of the discovery when she was not even in the country is a striking instance of this disturbing trait.

Schliemann also lied about the findspot. He apparently wanted to use the find to lend credibility to his identification of the rather unimpressive building within the gate as Priam’s Palace. In his first reports, he says he found the treasure “in a room of the palace.” Only much later, perhaps when he noticed that his engineer Adolphe Laurent had marked the true findspot just outside the city wall on the carefully drawn plan of the excavations, did Schliemann decide that it was easier to change his report of the findspot than to change Laurent’s plan. However, he still tried to link the treasure to the palace with the fanciful story of a member of Priam’s family escaping with a treasure chest and abandoning the chest on the wall and immediately next to “Priam’s Palace,” never addressing the fact that it was separated from the palace by the substantial width of the city wall! When he next made a plan of Troy (in 1881), he marked the findspot squarely on the wall, not outside it. All experts agree, however, that the true findspot was where Laurent indicated in 1873—outside the wall.

Schliemann lied, too, about the date of the discovery. It is now clear that the find was made on May 31. Schliemann’s first account of it is under an entry bearing that date. After his return to Athens in late June, he wrote up a new account of the discovery, dating the find to June 7. He wrote this in the same diary that contained the first version of the discovery under the date of May 31! In this new account he stated that he found the treasure in “a narrow room of Priam’s palace enclosed by two walls near the city wall as its runs N.W. from the Scaean Gate.” (Although it is hard to imagine how any room could be enclosed by two walls, there is just such a narrow space very close to the city wall a little north of the Scaean Gate). But this “narrow room” lay directly under Schliemann’s own wooden house, which he removed on June 3 to excavate the mound of earth beneath it. The room could not have come to light until about June 7. So Schliemann changed the date of the discovery to fit the findspot. He needed a findspot in Priam’s Palace. His diary showed that the findspot he wanted was not uncovered until about June 7. So the date of the discovery had to be changed, too.

If Schliemann could be cavalier about both the findspot and the date of discovery, what about the contents of the treasure? There is one other witness to the discovery whose testimony survives, Nikolaos Yannakis, Schliemann’s trusted personal servant and paymaster. His testimony is on all points much more reliable than Schliemann’s. For instance, he insisted that Sophia was not in Troy when the treasure was discovered and he placed the findspot not “on” but just outside the city wall. He remembered that there had been a great many bronze pieces, but was “hazy” as to the rest of the treasure. In this respect, his testimony resembles Schliemann’s earliest accounts of the discovery, written at Troy. In them Schliemann gives convincing accounts of the bronze pieces, but when it comes to the gold pieces, he cannot describe them. He explains that he had to pack them away quickly. But this was equally true of the bronze pieces. When he does try to describe one of them, the gold sauceboat, his description is so erroneous as to raise serious questions about when he last saw it: He says that because of its shape it can only be made to stand on its brim! The best available evidence therefore compels us to question whether the gold pieces were found on May 31.

The evidence regarding the jewelry is even more suspicious. There is no mention of it in the earliest accounts. It is first mentioned in the version written shortly after Schliemann’s return to Athens, and even there it is not included in the main description of the treasure but added as an afterthought—after his account of subsequent excavations.

One of the plates in the Atlas of plates that Schliemann published in 1874 to accompany the German and French editions of his excavation report is also suspicious. Some of these plates were actual photographs of the objects, taken after Schliemann had returned to Athens in late June 1873. Most of the plates relating to the 1873 excavations, however, were photographs of drawings made on site by Schliemann’s illustrator, Polychronios Lempessis. Plate 196 contains drawings of the 56 smaller earrings and a selection of beads. The heading now reads: “Trésor de Priam.” But it is clear that when the earrings were drawn, Schliemann had no intention of adding a heading, as no space was left for one.

The captions tell the same story. It is clear from their alignment that originally they simply read: “This plate contains 56 golden earrings and other gold jewelry (natural size),” in both French and German. To the German caption Schliemann added: “Everything from 8 1/2 meters deep.” To the French caption he added: “Everything comes from Treasure of Priam discovered at 8 1/2 meters deep.” Probably, then, the earrings were found at different depths in different locations. Only after his return to Athens, it seems, did Schliemann think of using them to add glamour to Priam’s Treasure, so he added the heading and amended the captions.

At least two of the granulated earrings seem far too late for Troy II (c. 2920–2420 B.C.). K.R. Maxwell-Hyslop, a leading expert on Anatolian and Near Eastern jewelry, sees unmistakable signs of Mesopotamian influence in these earrings and dates them to about 1900 B.C. or later.6 The current excavators of Troy, following the evidence of carbon-14 testing, now date the end of Troy II to about 2400 B.C.7 It is difficult to see how these earrings could have come from a Troy II stratum.

Clearly if Priam’s Treasure is a composite of different finds from the pre-Greek levels of Troy, it can no longer be considered a closed deposit. Many archaeologists, however, including the current excavators of Troy, defend the integrity of the find. While agreeing that Schliemann’s story about Sophia’s participation is a lie, they tend to attribute other discrepancies to confusion or rationalization on Schliemann’s part rather than to a deliberate attempt to manipulate the facts. Ultimately, of course, motives are irrelevant. If, as seems increasingly likely, Priam’s Treasure loses its status as a closed deposit, its diagnostic value is diminished. It will nonetheless still be of considerable archaeological significance. Nobody is suggesting that any of the pieces of Priam’s Treasure is a fake or was bought from dealers. All the pieces seem appropriate to Early Bronze Age Troy (Troy II-V, with a terminal date of about 1750 B.C.), even if some may be too late for Troy II.

Ironically, while the archaeological significance of Priam’s Treasure may be in decline, its value as a cultural phenomenon and tourist attraction seems to be increasing. Russia, Germany and Turkey have all staked out claims to ownership. The looming legal battle is certain to be protracted and will only add to the treasure’s glamour.8

MLA Citation

Endnotes

See David A. Traill, Schliemann of Troy: Treasure and Deceit (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995).

For more information on Frank Calvert, see Susan Heuck Allen’s Finding the Walls of Troy: Frank Calvert and Heinrich Schliemann at Hisarlik (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains (London: John Murray, 1875; New York: Dover, 1994), pp. 323–24. I have retranslated the passage to make it conform more closely with the German original.

For more details on Schliemann’s life and the history of the treasure, see Traill, Schliemann of Troy; for the period after his death, see Caroline Moorehead, Lost and Found: The 9,000 Treasures of Troy (New York: Viking, 1996); and for a good summary of the entire issue, see Donald Easton, “Priam’s Treasure: the Full Story,” Anatolian Studies 44 (1994).

Anthony Snodgrass, “Betrayer of the Truth” (review of David A. Traill, Schliemann of Troy), Nature 378 (Nov. 2, 1995), p. 113.

Manfred Korfmann, “The Value of the Finds to the Scientific Community,” in Elizabeth Simpson, ed., The Spoils of War (New York: Harry Abrams, 1997), p. 207.