013

Rabbath Ammon it was called in ancient times, a place-name we might translate as the Ammonite Heights. During the Iron Age, it was the capital of the kingdom of Ammon, rival of the biblical Israelites.

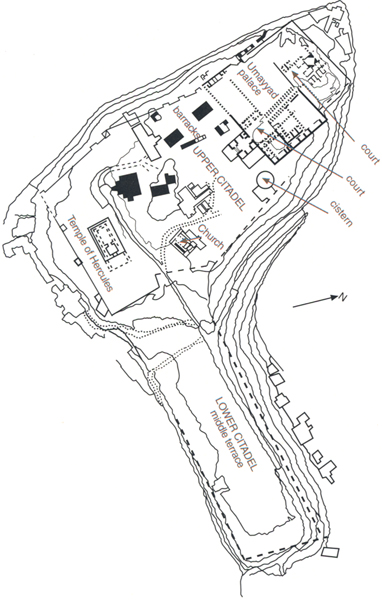

The remains of the ancient Ammonite acropolis are perched atop a rocky outcrop overlooking the bustling capital of modern Amman, Jordan. Known today as Jebel al-Qal’a, or the Citadel, the hill is an L-shaped plateau of about 40 acres divided into three levels, or terraces. Precipitous wadis (dry river beds) surround the plateau on all sides except the north. Below the southern flank—the long east-west base of the L—flows the Sayl Amman, which joins the Wadi Zarqa (referred to in the Bible as the Jabbok River) in its tortuous descent to the Jordan Valley.

The Ammonites were the descendents of Semitic groups that had occupied the area of Transjordan around Amman at least since the mid-second millennium B.C.E. The Bible, written from an adversarial viewpoint, identifies them more specifically as descendants of Ben-ammi, who was born of an incestuous union between a drunken Lot and his younger daughter (Genesis 19:38). In the period of the Judges, the Israelite commander Jephthah crossed the Jordan River “to attack the Ammonites, and the Lord delivered them into his hands” (Judges 11:32). Before the battle, Jephthah swore an oath that in return for a victory over the Ammonites he would sacrifice the first thing to greet him when he returned home—a compulsive vow that forced him to commit an unthinkable act:

When Jephthah arrived home in Mizpah, it was his daughter who came out to meet him with tambourines and dancing. She was his only child; apart from her he had neither son nor daughter. At the sight of her, he tore his clothes and said, “Oh, my daughter, you have broken my heart!” … And he fulfilled the vow he had made (Judges 11:34–39).

Indeed, the long arc of Ammonite history parallels that of the biblical Israelites—not surprisingly, since Amman is less than 50 miles from Jerusalem. Both flourished during the Iron Age (c. 1000–600 B.C.E.), fell to the Babylonians in the early sixth century B.C.E., and then submitted to Persian domination.

In the Hellenistic period, Rabbath Ammon was rebuilt and renamed Philadelphia, after Philadelphus II (285–246 B.C.E.), one of the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt. Later, as the capital of the Roman province of Arabia, established in 106 C.E., Philadelphia grew dramatically, sprawling off the Citadel and into the surrounding valleys. It was during this period that many of the town’s civic structures were built along the Sayl Amman, including the spectacular theater and forum still visible today.

The town continued to prosper in the early Islamic period under the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 C.E.), when Philadelphia was renamed Amman—the Arabic form of the ancient name. Ruling from Damascus, the Umayyads established Amman as a seat of provincial governors, one of whom built a luxurious palace on the Citadel.

014

With the rise of the Abassid Caliphate (750–974 C.E.) in Baghdad, Amman became less important and fell into decline. In the early 14th century C.E., the Arab geographer Abu al-Fida reported that Amman lay completely in ruins.a

Over the millennia, the Citadel’s inhabitants tended simply to remove earlier structures and build new ones on the natural bedrock. This means that very little has been preserved from the earliest periods. The site’s natural defensive position high on the outcrop and its proximity to dependable sources of water continued over the millennia to make it an attractive location.

It appears that the Citadel was first occupied in the Neolithic period, around 7,000 years ago. Excavators have also found pottery fragments dating to the Chalcolithic period (4500–3100 B.C.E.) and Early Bronze Age (3150–2200 B.C.E.), though these sherds were discovered in secondary or tertiary contexts. The most secure evidence suggests that the early settlement was confined to the lowest terrace of the Citadel. However, a number of caves cut into the slopes of the upper terrace contained pottery dating to the end of this period (c. 2200–2000 B.C.E.), perhaps indicating a shift in settlement to the higher level at this time.

The remains of substantial fortification walls and a glacis (a sloping rampart) date to the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 B.C.E.). The glacis formed part of an elaborate defensive system along the northern edge of the upper terrace, the only part of the Citadel not protected by a steep ravine. The middle and upper terraces were probably enclosed by walls as well.

Archaeologists have also uncovered three Middle Bronze Age tombs containing a wealth of artifacts: pottery vessels, scarabs, cylinder seals, ivory inlay, alabaster jars and metal objects. These tombs were cut into the southern part of the upper terrace, near a structure that may have been a temple. Although the Roman-period inhabitants leveled this entire area 015to build the huge Temple of Hercules, the Middle Bronze Age tombs and the apparent absence of other contemporaneous remains suggest that the upper terrace was considered a sacred precinct. This interpretation was strengthened by the discovery in 1987 of a large stone wall separating the upper terrace from the rest of the settlement, creating a kind of protected zone.

Surprisingly, all we have from the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.) settlement are some pottery sherds. If the Citadel was occupied during this period, it clearly did not support the sizable population that lived, worshiped and died there in the Middle Bronze Age. Rabbath Ammon does not appear, for example, on a list of Canaanite toponyms recorded by the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 B.C.E.) at Karnak—even though the pharaoh does mention several nearby sites, such as Krmn (possibly Tell al-’Umayri, south of Amman). Perhaps during this period a smaller settlement simply shifted to the currently inhabited—and thus unexcavated—part of the lower terrace (see plan of Philadelphia of the Decapolis in “Philadelphia of the Decapolis”).

What we do have, however, is an impressive Late Bronze Age building, possibly a temple, located a few miles east of the Citadel on the grounds of the former Amman civil airport. Discovered in 1955 during an expansion of the airport runway, this structure was made of stone and almost perfectly square, measuring close to 50 feet on a side. The building resembles an Egyptian-style residence from the Amarna period (14th century B.C.E.), and it contained a rich assortment of non-local pottery, stone vessels and jewelry, some imported from as far away as Egypt, Cyprus and the Aegean. The complex also produced large quantities of charred human bones, perhaps from cremation, identifying it as a possible mortuary temple.

In 1940, after completing a series of arduous treks across the rugged Transjordanian highlands, the American rabbi Nelson Glueck published an archaeological history of the region. In The Other Side of the Jordan, he argued that the highlands were virtually devoid of human populations for most of the second millennium B.C.E.; only with the onset of the Iron Age, around 1200 B.C.E., did people begin settling in the region. Glueck explained this growth as the emergence of the biblical kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom. He identified Ammon as a territory consisting of a series of hilltop towers guarding the approaches to the foothills around the capital, Rabbath Ammon. Glueck maintained that these defensive towers were built specifically to ward off the tribes of Israel as they passed through the region en route to their promised land.

The past 60 years of archaeological exploration have disproved some of Glueck’s claims. We now know, for example, that there were sizable sedentary populations in the region throughout the Bronze Age. Even so, surveys consistently uphold Glueck’s view of a dramatic settlement expansion in the highlands during Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.).

Excavations on the Citadel, however, have produced little more than residual sherd material dating to the early Iron Age. Nor do the literary sources referring to this period mention the site. The biblical account of Jephthah’s campaign against the Ammonites, for example, does not mention Rabbath Ammon, even though he would have had to pass it during the pursuit of his adversaries. The Ammonites of the early Iron Age, therefore, seem to have been a loose political entity, probably with a small 016community established on the Citadel.

Rabbath Ammon re-enters history at about the same time as the formation of the Israelite state, in the early tenth century B.C.E. According to the Bible, Nahash, a king of the Ammonites, dies and is succeeded by his son Hanun. King David (c. 1004–965 B.C.E.) sends a mission to Hanun with words of sympathy, but Hanun treats David’s men as spies and punishes them, in typical Ammonite fashion, by cutting off half their beards, cutting off half their garments and dismissing them. David seeks retribution by sending his general Joab to engage the Ammonites. Joab succeeds in severely weakening the enemy, and then David himself takes over. The Israelite king “marched on Rabbah, and attacked and captured it.” David then takes the golden crown of the Ammonite kings and places it on his own head (2 Samuel 10–12).

David later secures his hold on Rabbath Ammon with a marriage alliance between his son Solomon and Na’amah, an Ammonite princess. Under the influence of Na’amah, Solomon builds a sanctuary for the Ammonite god Milcom (1 Kings 11:7). Na’amah later gives birth to Rehoboam (c. 928–911 B.C.E.), Solomon’s successor and the first king of the southern Israelite kingdom of Judah (I Kings 14:21, 31; 2 Chronicles 12:13).

Archaeological excavations on the Citadel may provide evidence for part of this story. Joab, David’s general, apparently was able to weaken the Ammonites by capturing the “King’s Pool”: “I have attacked Rabbah and have taken the pool,” Joab writes in a dispatch to David in Jerusalem (2 Samuel 12:27). This very likely means that Joab captured Rabbath Ammon’s water supply, allowing the Israelites to overrun the town.

Salvage excavations in 1969 along the northern edge of the upper terrace uncovered structures dating to the tenth or ninth century B.C.E. Although the material had been severely disturbed by modern building, the excavators were able to delineate the outline of a city wall and possibly a gateway. Within the area enclosed by the wall, a 6-foot-high tunnel had been cut down through the bedrock to a stairway, which in turn descended into a large underground chamber 20 feet wide, 55 feet long and 23 feet high—parts of which were located outside (though below) the city wall.

017

This large underground chamber resembles hidden underground water systems at Megiddo and other Iron Age sites in Israel, so it is possible that it is indeed the “King’s Pool” captured by Joab, a reservoir that kept Rabbath Ammon’s citizens supplied with drinking water. This reservoir extending outside the walls of the northern part of the city—the one part of the city not protected by steep cliffs—was the weakest part of the town’s natural defenses.b

Following the death of Solomon, Ammon regained its political independence, and steadfastly maintained its isolation throughout much of the ninth and eighth centuries, choosing only periodically to participate in regional wars against the Neo-Assyrians. For example, an inscription on a 7.2-foot-high stela found in Kurkh, on the Tigris River in modern Turkey, recounts how the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (858–824 B.C.E.) defeated a coalition of 12 smaller kingdoms. One of these kingdoms was led by “Ba’sa, son of Ruhubi, from Ammon.” A later Assyrian king, Tiglath-pileser III (744–727 B.C.E.), boasted that he received tribute from “Sanipu of Bit-Ammon” (literally “House of Ammon,” the Assyrian designation for the Ammonite Kingdom). In all likelihood, it was during this period that the kingdom’s political and religious institutions were formalized, and Rabbath Ammon emerged as its ritual and ceremonial center.

Although excavations at Rabbath Ammon so far have identified little from this period, some developments point to the transformation of the town. In addition to the water installation at the northern part of the upper terrace, sections of a fortification wall have been found along the southern edge of the lower terrace. It seems that the entire Citadel was enclosed within an extensive defensive system at this time. There were probably other monumental structures as well. In 1961 the Citadel’s excavators discovered a small stone slab (about 7.5 inches by 10 inches) with a dedicatory inscription in Ammonite. Dated paleographically to the mid-ninth century B.C.E., the text on the slab commemorates the construction of a public building, possibly a temple to the god Milcom, whose name appears in the first line of the fragment (see the second sidebar to this article).

Excavators have also found numerous statues from this period depicting noble or royal figures. One statue is inscribed as depicting “Yarah-azar, son of Zakir, son of Shanib.” This “Shanib” is possibly the “Sanipu of Bit-Ammon” listed as a tribute-payer in the Tiglath-pileser inscription already mentioned. We thus have the names and relative dates of three Ammonite kings from the latter part of the eighth century B.C.E.—all suggesting that the Ammonite capital was a substantial city, a seat of royalty.c

Rabbath Ammon enjoyed great prosperity during the seventh century B.C.E. as a vassal state of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Assyrian influence is vividly apparent in seventh- and sixth-century B.C.E. statuary found at Ammon, including carvings of the Assyrian goddess of love and war, Astarte. Virtually every sounding on the Citadel has produced well-preserved remains from this period. Excavations on the lower terrace, for example, have uncovered a 018large building reminiscent of Assyrian palatial architecture. Described as an elite residence by the excavators, the complex consisted of a large open courtyard, 33 feet by 50 feet, surrounded by a series of rooms, whose floors were covered by a fine white plaster. The building looked out onto a well-paved street and contained imported pottery, Phoenician ivories, lapis lazuli and other luxury items.

The Citadel’s upper terrace has also yielded numerous remains of the late Iron Age city. Recently, excavations conducted as part of the Temple of Hercules Project have uncovered a series of architectural features, including the remains of a monumental building constructed of megalithic limestone boulders. Its location within what may have been a sacred precinct in more ancient times—and what certainly was a sacred precinct in Roman times—points to a religious function, perhaps even a temple to Milcom or some other Ammonite deity. The recovery of six votive figurines in the debris associated with the building gives some support to such an interpretation.

The prosperity of this pax Assyriana is also evident in the wealth displayed in the necropolis that grew up around the city, in the technical skill of Ammonite sculptors and potters, and in the proliferation of epigraphic material in the area. The collapse of the Assyrian Empire at the end of the seventh century B.C.E. brought this era of peaceful coexistence to an end. The Neo-Babylonian Empire assumed most of the Assyrian territory. In 605 B.C.E. King Nebuchadnezzar, ruler of Babylon, invaded the Levant, sacking the Philistine city of Ashkelon on the Mediterranean coast in 604 B.C.E., and, after almost two decades of further conflict, destroyed Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E. Just four years later, 019the Ammonite capital of Rabbath Ammon also fell to the Babylonians.

The Ammonites may have been partially responsible for their own demise. According to the Bible, the Babylonians appointed a man named Gedaliah to act as governor of the region following the destruction of Jerusalem. Shortly thereafter, Gedaliah was assassinated by a disgruntled military officer with ties to the former royal family, and the remaining inhabitants of Judah fled to avoid retribution by the Babylonians (2 Kings 25:22–26). Gedaliah’s assassination was apparently instigated, however, by an Ammonite king named Baalis (Jeremiah 40:14).

Archaeology has provided an interesting link to this Baalis. A seal impression found in 1984 at the Ammonite site of Tell al-’Umayri reads, “Belonging to Milkom’or, servant of Baalyasha.” There are several reasons to identify Baalyasha as the biblical Baalis. For one, the theophoric element “baal” (a theophoric element is the name of a deity, like Milcom or Baal, included in the name of a person) is extremely unusual in Ammonite names. Also, the writing on the impression can be dated by paleography to about the early sixth century B.C.E. Finally, the impression bears an image of a four-winged scarab—a symbol of royal authority in the Levant.

So it appears that the Ammonite king Baalyasha, by instigating the assassination of the regional governor, may have incurred the wrath of Babylon. In any event, the fall of Rabbath Ammon marked the end of the Ammonites’ existence as an independent people.

But this was not the end of the Citadel’s place in history. The story continues in the exciting article that follows.

Rabbath Ammon it was called in ancient times, a place-name we might translate as the Ammonite Heights. During the Iron Age, it was the capital of the kingdom of Ammon, rival of the biblical Israelites. The remains of the ancient Ammonite acropolis are perched atop a rocky outcrop overlooking the bustling capital of modern Amman, Jordan. Known today as Jebel al-Qal’a, or the Citadel, the hill is an L-shaped plateau of about 40 acres divided into three levels, or terraces. Precipitous wadis (dry river beds) surround the plateau on all sides except the north. Below the southern flank—the long […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

The modern revival of the city began a little more than a century ago, when Circassians from east of the Black Sea were relocated to the area by Ottoman authorities. In 1921 King Abdullah made Amman the dynastic seat of the Hashemite family. Since then, the city has grown into a thriving metropolis of more than 2 million people.

The German scholar Ulrich Hubner has proposed that this “city of the waters” was located down below the Citadel, near the later Roman forum, where excavators have found pottery dating from the eighth to the sixth century B.C.E. However, maintaining the city’s water supply that far from its defenses would have left its inhabitants exposed and vulnerable to attack.