022

Familial tension in the Bible is typically sibling rivalry, rather than Oedipal conflict. We are hard put to find examples of a struggle between parents and children in Genesis, although the popularity of the Greek myth would lead us to expect to find this as the prototype for all family stress. Instead, Scripture offers us example after example of the rivalry of brothers—Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau, Joseph and his brothers.

And of sisters. Distressing though these episodes of sibling tension are, the most tragic example of sibling antagonism is between Rachel and Leah. (To review the familiar—but complex—story of Rachel and Leah, see the first sidebar to this article)

With Rachel and Leah the jealousy of sisters is compounded by their being wives of the same husband, a practice so frowned upon that it was placed amidst the central list of forbidden sexual relations in Leviticus: “Do not marry a woman as a rival to her sister and uncover her nakedness in the other’s lifetime” (Leviticus 18:18).a In view of this explicit prohibition, the question naturally arises: How could Rachel and Leah’s marriage to a single husband have occurred in the first place? While polygamy was permitted by biblical law, Jacob’s marriage to Rachel and Leah was not simply polygamous but involved two sisters marrying the same husband. The biblical prohibition against this is unmistakable. How did Jewish tradition deal with it?

Several answers have been suggested: The proscription against such a marriage was not yet in effect when this liaison occurred, the giving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai having followed by many centuries the events of story. This same reason is also 023used to explain how Abraham could have served his guests a meal of meat together with milk (Genesis 18:8), clearly contrary to the dietary laws expressed in Exodus 23:19. Although the rabbis assumed the patriarchs observed all the laws of the Torah even before they were given at Mt. Sinai, some say that this applied only when the patriarchs resided in the land of Israel but not outside the land—such as in far-off Haran where Jacob married both Leah and Rachel. Another suggestion is that there was divine sanction to violate the law in this particular case, because the future progeny of these marriages would comprise the heads of the 12 tribes of Israel. Still another explanation: Because Leah and Rachel each feared that whichever of them did not marry Jacob would become the wife of his brother Esau, God decided to give them both to Jacob.1

Whatever the justification for the marriage two sisters to the one man, it is clear that as cowives they were in an untenable situation. After all, both loved the same man, both sought his love, both wished to be the mother of his children and both felt envy of the other. Thus, “when Rachel saw that she had borne Jacob no children, she became envious of her sister” (Genesis 30:1); for her part Leah complained: “You have taken away my husband” (Genesis 30:15).

The dramatic development of the Rachel/Leah story reflects a divine pendulum, now swinging toward one sister, then toward the other. At first the movement is in the direction of Rachel, the young, beautiful shepherdess whose first meeting at well evokes Jacob’s love; then Leah, favored by the custom of marrying off the elder sister first, substituted for Rachel on her wedding night; then Rachel, who Jacob insists be given to him as wife as well; then Leah, who because “the Lord saw she was unloved, opened her womb” (Genesis 29:31)025 to an abundance of sons for Jacob, while Rachel remained barren; then Rachel, whose chosen maid gives two sons to Jacob so “that through her [Rachel] too may have children” (Genesis 30:3); then Leah, whose maid also bears sons, followed by Leah herself; and, finally, the pendulum rests with Rachel, whom God “remembered… and opened her womb,” (Genesis 30:22) so that she conceives and, at last, bears her first son, Joseph.

This fast-moving theater, in typical biblical style, is tightly condensed into the fewest possible verses—even more compressed in Hebrew than in translation— half concealing worlds of hope and despair that later writers expanded on endlessly.

The Rachel/Leah conflict focuses on the contest between love and motherhood. Is there some scale of priority to choose between them? On the one hand, continuation of the covenant between God and his people requires children; on the other, true marriage demands love. Is succession so important that it can be satisfied with loveless children? It would seem so, for despairing of bearing children themselves, both Abraham’s wife Sarah and Jacob’s wife Rachel present Abraham and Jacob, respectively, with their maids to bear children in their stead. Conversely, can a childless love-marriage succeed? We hear no complaint from Jacob about Rachel’s barrenness in the years before she conceives. (Is it because he had children through Leah ?) But neither Rachel nor Leah were satisfied with their lot. Each wanted both love and motherhood. The struggle between them is nowhere given so clearly as in the names the sister-wives—never the father—give to their natural and surrogate children. In biblical days names were not given for their caressing sound or endearing association, or even to carry on a family name, as is the custom today; rather, names were intended to capture and convey the meaning of the life they denoted. At the birth of each of Jacob’s children, they are given a name by Rachel or Leah, followed immediately in the text by an explanation of the name. The explanation expands on the meaning of the Hebrew elements of the name. These names clearly express the motherhood-love tension: Rachel, possessing Jacob’s love but seeking mother; Leah, possessing motherhood but seeking Jacob’s love.

Consider how the names, and the meanings of the names ascribed to them by Leah, express her yearning for Jacob’s love:

Reuben (Hebrew:

÷bwar , “see” + “son”) = “See, God has given me a son and surely now my husband will love me.”Simeon (Hebrew:

÷w[mv , “to hear ”) = “The Lord heard that I was unloved and has given me this one also.”Levi (Hebrew:

ywl , “to join” = “Now will my husband be joined to me, for I have borne him three sons.”Genesis 29:32–34

Leah already had Jacob as husband-father, but she wanted his love as well. Herein lies the tragedy of Leah’s life. For how was she to gain that love? Can love be cajoled, commanded, produced by publicity, called up on demand, summoned by fiat or tears— or through children? Must it not emerge of itself, if is to emerge at all? And of that, there was little possibility in the shadow of Rachel, whose romance with Jacob was immediate and decisive, exceptional and persistent, and contrary to the then normal 026pattern whereby marriage precedes love. Jacob’s love for Rachel was the love of passion, a mutual passion which is “necessarily exclusive. ”2 What room, then, could there be for Leah? Was she not forced upon Jacob through intrigue by her father, who claimed to be bound by the custom of the land to marry the elder daughter first, and did she not cooperate in the scam, according to some rabbinic commentaries, lest she be compelled to wed the wicked Esau? She would not have Esau, as Jacob would not have her. Whom she can have, she does not want; whom she wants she cannot have. (The same can be said for Jacob when Laban substitutes Leah for the beloved Rachel: Whom he can have, he does not want; whom he wants he cannot have.)

What could Leah have reasonably expected from Laban’s intrigue? One Midrashb turns the screw tighter by having her exacerbate Jacob’s anger when he discovers the substitution. Leah is said to have rebutted Jacob’s outrage by pointing out that when she impersonated her sister by deceptively responding to his call for Rachel in the darkness of the nuptial chamber to win him as her husband, she was doing no more than Jacob himself had done in the darkness of Isaac’s blindness, when Jacob impersonated his brother by deceptively responding to his father’s call for Esau to gain the birthright: “He went to his father and said, ‘Father.’ And he said, ‘Yes, which of my sons are you?’ Jacob said to his father, ‘I am Esau, your firstborn’ ” (Genesis 27:18–19).

Could Leah hope for love under those circumstances? True, Heaven took pity and granted her children when Rachel had none, and this must have stirred Jacob. But love? Not according to the underlying meaning of the names she continues to give her children. Jacob seems to have all but ignored Leah; not in a single instance does Jacob speak directly to her alone. During the years when Leah’s children were being born, and he might have seemed most receptive, Jacob was toiling a second seven-year stretch for Rachel! When he speaks of his wife in later years, when Leah alone is still alive, It is Rachel to whom he always refers. In these circumstances, Leah’s dogged resolution, expressed in the names she continues to give her children, is remarkable. While the sages make much of Leah’s “restraint,” finding in it a piety of sorts, these names are as close to a protest as she comes and point to Leah’s perseverance, which is confirmed by Rachel’s sharp reaction after the birth of Judah, Leah’s fourth son:

“When Rachel saw that she had borne Jacob no children, she became envious of her sister; and Rachel said to Jacob, ‘Give me children or I shall die!’ Jacob was incensed at Rachel, and said ‘Can I take the place of God who has denied you fruit of the womb?’ ” (Genesis 30:1–2).

Rachel’s brusque demand seems out of character, unless we see it as the outburst of a woman who could no longer restrain her pent-up frustration, heightened over years of watching one son after another born to Leah, while she had none. How could she be a wife, even if beloved, without being a mother? Perhaps the implicit rivalry of the sisters foretells the later rivalry between the sons of Leah and Rachel’s, son, Joseph, and between the tribes descended from the two matriarchs in the land of Israel.

Jacob’s sharp reply to Rachel’s demand/complaint—“Can I take the place of God, who has denied you fruit of the womb?” (Genesis 30:2)— seems equally out of character. Why was he not more sympathetic, asks the Midrash? Was she not his beloved wife, and was it not natural for her to want children after such a long and vexing wait? Quoting Isaiah— “I have given them, in My house and within My walls, a monument and a name better than sons and daughters” (Isaiah 56:5)—a later sage defends Jacob, arguing that his vexation was meant affectionately. What Jacob intended by his outburst was that, though he would have wished 027Rachel to be the mother of his sons, his love for Rachel was unconditional; he would love her even without children. “Am I not more devoted to you than ten sons?” (l Samuel 1:8).

In contrast to the names of Leah’s children, which signal her desire to win Jacob’s love, the names of Rachel’s children, the first two of which are born to Bilhah, her maid, point to her unrelenting drive for motherhood

Thus: Dan (Hebrew:

÷d , “to vindicate ”) = “God has vindicated me and given me a son.“Naphtali (Hebrew:

yltpn, “to contest ”) = “I have waged a contest with my sister, and prevailed.”Genesis 30:6–7

In explaining the name Naphtali, Rachel herself reveals the protracted conflict with Leah. The tension between the sisters seems inescapable. For all Rachel’s jubilation at the birth of her maid’s children, her celebration has as hollow a ring as did Sarah’s on the birth of Ishmael to her maid Hagar. Though Rachel claims and names the boys as her 040own, quite as she told Jacob she would when she changed him: “Consort with [Bilhah], she may bear on my knees and that through her I too may have children” (Genesis 30:3), these children were, after all, born not to her but not to a surrogate, leaving her as much an akara (a barren woman) as before.

Rachel’s joy in “prevailing” is, in any event, short-lived, for Leah, not to be outdone by her sister, follows suit only too quickly by using her maid Zilpah as surrogate. So Gad and Asher are born.

Then, unwilling to wait any longer, perhaps in remembrance of her grandmother Sarah who bore Isaac when “Abraham was one hundred years old” (Genesis 21:5), Rachel begs for mandrakes—an ancient love-potion—in return for which she permits Leah to return to Jacob’s bed. Leah then bears Issachar and Zebulun, and with the naming of Zebulun (Hebrew:

Against Leah’s own six sons and a daughter, plus her maid Zilpah’s two sons, Rachel can count only two sons, and those two by virtue of Bilhah, her maidservant! The odds weigh more and more heavily on the side Leah. At this point in the story, when defeat has followed defeat and all hope seems lost, Rachel’s deepest desire is at long last fulfilled with the birth of a child. Her words upon naming him must reflect her deepest feelings: “ ‘God has taken away my disgrace.’” So she named him Joseph [Hebrew:

Motherhood is Rachel’s consuming concern. The disgrace of her barrenness has been removed with the birth of this child. But the name she gives him expresses neither thankfulness for the child nor a reference to her husband. Her mind’s eye sees beyond this son to the next; this one is meant only to be forerunner of the many she prays will follow. Rachel’s reproach of barrenness is indeed gone, but the completion of her task as a mother in her eyes, only beginning.

The divine pendulum swings again between the sisters and comes to rest at last—in the direction of Rachel.

Contrary to the apparent intention of story and Jacob’s expressed preference for Rachel, some writers find Leah the more desirable of the sisters. Leah, who was healthy in body and whole in spirit, needed neither the mandrake love-potion for which Rachel bargained to bear children, nor their father Laban’s idols for her religion. In addition, Leah’s conversion to Jacob’s religion has been seen as evidence of piety superior to that of Rachel. While both sisters took upon themselves the patriarchs’ faith in the one God, Rachel’s conversion was tainted by her need to convert in order to marry the promised Jacob, while Leah’s conversion had no such flaw.3

Another favorable view of Leah is that her “weak” eyes, far from being a sign of physical disability, were evidence of moral strength. For just as the younger children (Rachel and Jacob) were destined to marry each other, so were the older children (Leah and Esau) meant for each other. Leah, well aware what marriage to the pagan Esau would mean, wept uncontrollably, thus damaging her eyes; though the marriage between Leah and Esau had been arranged by divine fiat, such was the fury, the passion and the pity of Leah’s tears that the heavenly decree was annulled.4

Nor was Leah passive in her substitution for Rachel on Jacob’s wedding night. For reasons of piety and not romance—aversion to Esau’s evil and attraction to Jacob’s goodness—she permitted herself a role in the deception. It was only necessary for the lamp of the bridal chamber to have been put and for Jacob, whose wits had, in any case, been dulled through drinking long and late the night of the wedding feast, to have had his calls for “Rachel” answered by Leah. Not until the next day did Jacob awake to the deception: “When morning came, it was Leah!” (Genesis 29:25)5

In search of praise for Leah, one comes upon the tale of the miraculous exchange embryos! A rabbinic extrapolation of the text tells us that Rachel’s first pregnancy was not with Joseph but with Dinah (who was eventually born to Leah); Leah, on the other hand, was originally pregnant with Joseph, not Dinah! But Leah had divined that Jacob would ultimately be the father of 12 (male) heads of tribes. Were Leah to bear a son there would be room for only one more (11 having already been born: seven from her and two from each of the maids). Leah—according to this retelling—felt it would be unjust to Rachel, even if Rachel succeeded in becoming the mother of Jacob’s twelfth son, to be inferior to the maids, each of whom had two sons. If this were to occur, Rachel would never achieve the status of a matriarch. How could Leah help her sister Rachel who had remained “silent” on that night that was to have been Rachel’s long awaited wedding night? Leah prayed to switch the unborn children (Joseph and Dinah), and by this act to repay Rachel for allowing the switching of the sisters on the wedding night. Thus Leah entreated that the fetuses be exchanged, one for the other. “And so it was… afterwards [i.e., after Leah’s prayers], she gave birth to a daughter and called her name Dinah [Hebrew:

Some of the mystics, as well, suggested the superiority of Leah, contending that Rachel represented the alma d’itgalya, the visible stage of the people Israel’s task, the worldly and tangible aspect. Leah represented the alma d’itkasya, the invisible stage, the spiritual, recondite world. Leah’s eyes, though “weak” in natural vision, were thought to have penetrated the mysteries. Taking these two stages as our platforms, the visible and invisible, it is possible to construct two periods in the patriarch Jacob’s life: the first, when he is devoted to earthly, perceivable tasks, such as contending with the intrigues of Laban, gaining a livelihood, building a family and facing Esau, during which time Rachel was his mate; the second, after his physical conquests were completed, when his name was changed to Israel and his labors turned more to the invisible world, during which time Leah was his only wife, Rachel having died in childbirth. These two roles of the matriarchs—the worldly and the spiritual—are further suggested by their places of burial. Rachel was buried by an open road on the way to Ephrath (Genesis 35:19) that she might rise up to comfort the exiles who would one day pass by on their way to Babylon (Jeremiah 31:15), while Leah was laid to rest within the hidden recesses of the Cave of Machpelah, alongside Jacob/Israel and the other patriarchs (Abraham and Isaac) and matriarchs (Sarah and Rebecca) (Genesis 49:30–31).7

Whatever the merit of the arguments favoring Leah over Rachel, they cannot stand against 041contrary opinions provided by the widest range of Jewish and non-Jewish literature. The physical contrast between the two, for example, is a favorite point of Christian writers, Chauncey Depew observes:

“I have often wondered what must have been his emotions when on the morning of the eighth year [Jacob] awoke and found the homely, scrawny, bony Leah instead of the lovely and beautiful presence of his beloved Rachel.”8

Nor should we be surprised that even so knowledgeable a scholar as the poet Robert Browning, who knew the Bible in Hebrew, follows the pattern, most commonly found in pictures of Jesus until Rembrandt, of favoring the Aryan “Rachel of the blue-eye and golden hair” over the Semitic visage of “swarthy skinned” Leah.9 The Jewish sages observed that each sister knew the man for whom she was destined, and, as the time of their betrothals drew near, the more Leah heard about the wickedness of Esau, the more her tears detracted from her appearance, while the more Rachel heard about the virtues of Jacob, the more beautiful she became.10 When Jacob first met Rachel at the well, he was so taken with her that he recited a blessing. For “upon seeing human creatures of unusual beauty, one should say, ’Blessed are You, O Lord, Who has such as these in Your world!’ And there was none so fair as Rachel. It was for this that Jacob wanted to marry her.”11

Other commentators attempt to refute the arguments cited above in Leah’s favor, So, for example, the suspicion cast on Rachel for carrying away Laban’s idols for her own use is rejected in favor of the view that even at the last moment of departure she continued trying to wean her father away from idolatry. By stealing his terafim, Rachel attempted to prevent him from enjoying his idol worship. Further, when Scripture says that Rachel was jealous of Leah, those who elevate Rachel explain that it was Leah’s piety and not her fertility that she envied.

But the central event in Rachel’s life that later writers focus on in a hundred different ways to laud her character is her quite remarkable silence at the time of Leah’s substitution for herself in the marriage chamber—at the very moment when Rachel’s dreams of marriage were to be consummated after seven long years of waiting. This restraint is regarded as one of Rachel’s noblest features. As the Hasidic master, Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev, tells it, “The merit of [Rachel’s] selflessness during the substitution of Leah for herself, lest her sister be put to shame, still succors us.”12

Surely Rachel’s decision to remain silent could not have been Without anguish then or torment later. But in the brief space within which the tale is told—the more momentous the event the terser the biblical description—only the bare bones are given, with no hint as to Rachel’s inner feelings. All the more reason for the masters of the Midrash to dig them out. Thus, the name Rachel gives to one of her maid’s children, Naphtali (“to contest”) and the meaning she gives for the name—“I have waged a contest [niphtalti] with my sister” (Genesis 30:8)—is turned by the Midrash into an inner grappling:

“I wrestled mightily with myself over my sister’s plight, I had already perfumed the marital bed. Rightfully, I should have been the bride, and could have been, for had I sent a message to Jacob that he was being deceived would he not have abandoned her on the spot? But I thought to myself: if I am not worthy to build the world, let it be built by my sister,”13

Another defense of Rachel: When Scripture says that “God remembered Rachel … and opened her womb” (Genesis 30:22), the Midrash takes it to mean that God remembered “that she was silent when Leah was placed in her stead,” But was there not more to be remembered than her silence at the time of marriage? What of all the years after the wedding when she did not cry out? For she did not. And should you object that Scripture states quite the contrary—“Rachel envied her sister” (Genesis 30:1)—understand that it intends but to tell us that she envied the piety and the good deeds of her sister! This is the reason why there is no substance to the claim that Rachel did not deserve to have been rewarded with a child, because she was a sinner who violated the prohibition against a second sister marrying the same husband during her sister’s lifetime. Scripture’s justification in forbidding such a marriage, namely, to prevent sisters from becoming rivals (tzarot) (Leviticus 18:18), was not applicable to Rachel, since she was never jealous of her sister (except for her piety), either at the time of the marriage or later.14

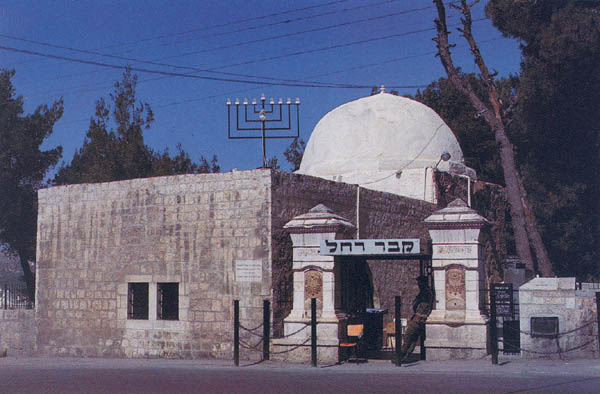

For the mystics, too, despite their esteem for Leah, it is Rachel who is victorious, In good measure because of their Veneration of Rachel’s traditional gravesite, along the road to Bethlehem, that spot became, together with the Western Wall of the Temple and the Cave of Machpelah (the burial site of the patriarchs and matriarchs in Hebron), one of the three holiest points of pilgrimage in the Holy Land, Rachel’s compassion, explains the Zohar,c was such that she “achieved more than any of the patriarchs, for she stationed herself at the crossroads whensoever the world was in need,” If Jeremiah turned the burial place of Rachel along the road to Bethlehem into a sepulcher from which she would arise to comfort the exiles on their way to Babylon a thousand years after her death (Jeremiah 31:15), the mystics transposed her gravesite into a station from which a merciful messenger would emerge from time to time through the centuries to bring solace and hope to the bereft. Indeed, they went so far as to give her name to the Shekhinah, the Indwelling Presence of God, who accompanies the people Israel in their exiled wandering and shares in their suffering.15

Once Rachel dies, Leah bears no other children. Nor is Leah recorded among the consolers of Jacob after Joseph’s disappearance. Nor is Leah mentioned during Jacob’s residence in Egypt. Nor are we told of her death. Indeed, nothing more is said of her, apart from two references in chronologies and a notice that she had been buried in the Cave of Machpelah. Just as the exclusivity of Jacob’s love for Rachel left no room for Leah during Rachel’s lifetime, so after Rachel’s death, Jacob’s inconsolable mourning continues to eclipse Leah and banish her from the scene.d

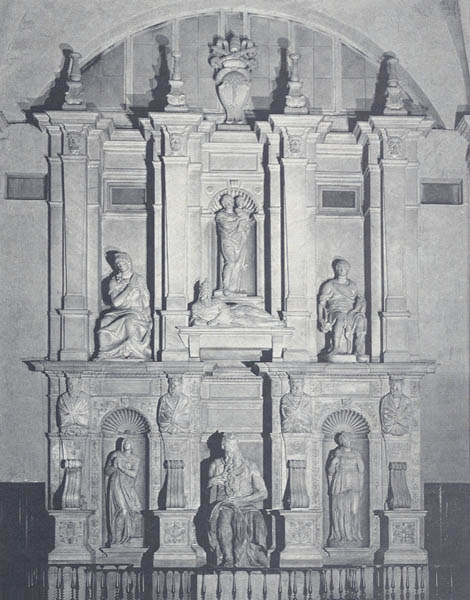

A comparison of the sisters of another sort is found in Michelangelo’s last sculpture, the great tomb of Pope Julius II. Pope Julius is depicted above a central statue of Moses with 042Leah and Rachel on either side of Moses, portraying, respectively, the active and contemplative life. Michelangelo followed the lead of Dante, who characterized the sisters this way.16 To Moses’ right, Michelangelo depicts Rachel dressed as a nun in prayer, symbolizing the contemplative life; to Moses’ left is Leah, symbolizing the active life of good works. Though, according to the church, both ways are principal avenues in the service of God, it is clear which sister is being favored.

“The Rachel [statue] is the more expressive, elongated in prayer and ’with her face and both her hands raised to heaven so that she seems to breath love in every part,’ as [Michelangelo’s biographer, Ascenio] Condivi wrote. Michelangelo clearly thought of her as a representation of faith. He spiritualized her in convent garb to the detriment of the stolid, earthy Leah.”17

A final but unspoken argument for Rachel is delicately woven into the intrigues of the tale—an argument for monogamy. The struggle for a worthy family is central to the handing down of Israel’s covenant with God: The creation of a worthy family is the primary function of the patriarchs and the matriarchs. The principle reason for avoidance of the Canaanites as marital partners related to their sexual practices, as graphically spelled out in Leviticus 18. Monogamy was the marital ideal not only in the utopian society of the Garden of Eden with Adam and Eve, but also when paradise ends and “history” begins: Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob and Rachel.

Even the concubine-maidservants provided to Abraham by Sarah and to Jacob by Rachel when they could not conceive prove to be troublesome. The maidservants cause conflict in the marriages. When Sarah’s maid Hagar became pregnant, “she despised her mistress”; Hagar’s son, Ishmael, “was like a wild ass whose hand was against every man” (Genesis 16:4, 12). Rachel’s maid Bilhah had a liaison with Reuben, the eldest son of Leah, which led to his loss of the birthright. The maidservants prove to be stumbling blocks to monogamy, just as Leah herself is.

Indeed, Leah is the single exception to the monogamous pattern among the patriarchs. Her role is anomalous. She is a bearer of children, as were the maids, but she is also Jacob’s legal wife, as was Rachel. The case of Leah, it could be argued, made a biblical argument for polygamy—except that the burden of the biblical story is the reverse; its purpose is to tell us that such an arrangement simply does not work. Despite her legal standing, Leah knows that she is not recognized in Jacob’s eyes as Rachel’s equal. Despite Laban’s scheme, Rachel’s kindness and Leah’s compliance Jacob would not love Leah. He did not love Leah even after their children were born. His love was for Rachel, from first to last. Passion’s exclusivity left no room for Leah. Leah appears as an outsider from the beginning. She is thrust upon Jacob by deceit, while Rachel is loved and chosen. Leah is fertile, conceiving (according to one sage) at the very first encounter, while Sarah, Rebekah and Rachel, to whom Leah is related by blood (the grandniece of one, the niece of the other and the sister of the third), were all initially barren. Furthermore, Leah’s numerous children, described so harshly by Jacob on his deathbed, are the source of much misery: The brothers’ kidnapping of Joseph; the firstborn Reuben’s affair with Rachel’s maid Bilhah (the mother of two of his stepbrothers), for which crime the birthright was taken from him and given to Joseph; the defilement of Dinah; and Simeon and Levi’s cruel slaughter of the Shechem clan.

The separation between love and child bearing was common in antiquity. Polygamous societies accept a multiplicity of mates, while monogamous societies must contend more with adultery, prostitution and divorce. Leah and Rachel seem at first to serve the separate polygamous roles of maternity and affection. But neither is willing to settle for that; each demands both. Only Rachel, however, achieves it. The story reflects a kind of monogamy related to the bearing of children: the sisters do not bear at the same time; when Leah bears, Rachel is barren, and when Rachel’s maid Bilhah bears, Leah is barren, and so on. It is as if something were wrong with both wives bearing at the same time.18

When the relationship between God and Israel is compared to a married couple, the human model is not that of fertile Leah/Jacob, whose love is mutual and exclusive

We have focused on the rivalry between Leah and Rachel. Let us end, however, by considering an intriguing commentary that reconciles the tension between the sisters and removes all bitterness from Jacob.

The Hasidic rabbi Levi Yitzhak reflects on Genesis 29:30: “He [Jacob] loved Rachel more than [or “rather than”] loved Leah ”e

While translations differ somewhat, they agree that Jacob favored Rachel over Leah. Levi Yitzhak, however, gives us quite a difference reading: “He loved Rachel even more because of Leah.” How does he defend this rendition, which is quite possible given the Hebrew words themselves?

“It is clear that while Jacob’s purpose in working for Laban was to marry Rachel, Jacob, in fact, married Leah. But Rachel [by her silence] was actually responsible for this. Jacob’s love for Rachel was then twofold: he loved her for herself, but he loved her even more because she brought him so pious a wife as Leah.”19

Levi Yitzhak’s vision turns the story on its head—no tension between sisters, no clash between motherhood and love, no anguish of a duped husband. All familial warfare vanishes. The matriarchs, to him, are models demonstrating how to overcome family unhappiness through the power of love and the example of piety. Far from Rachel envying Leah, she was responsible for the marriage; and far from Jacob resenting the deception, his love for Rachel is only enhanced thereby. Human kindness and nobility of character conquer society’s flaws. The tale is no longer, nor was it ever in Levi Yitzhak’s view, one of sibling tragedy; it is the record of the trial and the victory of Leah’s piety, Rachel’s compassion and Jacob’s love for the one and respect for the other.

The editors wish to express their thanks to Dr. Zefira Gitay for her aid in choosing the illustrations that accompany this article and for sharing her insights on them with us.

Familial tension in the Bible is typically sibling rivalry, rather than Oedipal conflict. We are hard put to find examples of a struggle between parents and children in Genesis, although the popularity of the Greek myth would lead us to expect to find this as the prototype for all family stress. Instead, Scripture offers us example after example of the rivalry of brothers—Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau, Joseph and his brothers. And of sisters. Distressing though these episodes of sibling tension are, the most tragic example of sibling antagonism is between Rachel and Leah. (To review the familiar—but […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Biblical quotations and verse citations are from the New Jewish Publication Society (NJPS) translation (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1985). Where the phrasing in this article differs from the NJPS, the translation is the author’s.

The Book of Jubilees, an apocryphal Jewish work, gives us a different picture of Jacob’s relation to Leah. “And Leah his wife died in the fourth year of the second week of the forty-fifth jubilee, and he buried her in the double cave near Rebecca his mother, to the left of Sarah, his father’s mother. And all her sons and his sons came to mourn over Leah his wife with him, and to comfort him regarding her… For he love her exceedingly after Rachel her sister died; for she was perfect and upright in all her ways and honored Jacob, and all the days that she lived with him he did not hear from her mouth a harsh word, for she was gentle and peaceable and upright and honorable. And he remembered all her deeds which she had done during her life, and he lamented her exceedingly; for he loved her with all his heart and with all his soul” (Jubilees 36:21–24),”

Endnotes

Babylonian Talmud, Baba Batra 123a: Genesis Rabbah, ed. H. Freedman (London: Soncino, 1939), vol. 2, p. 653 (71:2)

Torah Shlema, ed. Menachem Kasher (New York: Shulsin ger; 1951) vol. 5, p. 1198. When Dinah was born, the biblical text reads, “Afterwards, she bore a daughter” and not, as for all of Leah’s other births, “she conceived and bore …” The explanation for this change is that Leah did not conceive a daughter but a son. This is the force of “afterwards,” understood to mean: after she conceived a son, she bore a daughter. See Torah Temima, ed. Baruch Epstein (Tel Aviv: Am Olam, 1951), vol. 1, p. 279, to Genesis 30:21

H. Hibbard, Michelangelo (New York: Vendome, 1978), p. 174. While the Zohar sees Leah representing the “hidden world” and Rachel the “public world,” Dante, and Michelangelo following him, portray them as the opposite, Leah symbolizing the “active life” and Rachel the “contemplative life.”