030

031

In 1986, two years into the excavation of the Uluburun shipwreck, the team from the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, led by George F. Bass and Cemal Pulak, made one of its most remarkable discoveries. While sifting through the sediment of a large pithos that contained the remains of pomegranates, bronze implements and some ballast stones, 032they found the world’s oldest book!1

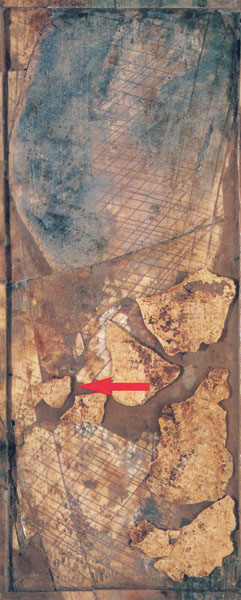

The book—a small, hinged writing board from the late second millennium B.C.—was reassembled from 25 fragments by Robert Payton at the Museum of Underwater Archaeology at Bodrum, Turkey. It is a diptych, consisting of two rectangular wooden leaves, each 2.5 inches wide and 3.5 inches high, joined by three ivory hinges. Both interior sides are recessed to a depth of about a tenth of an inch to hold wax, leaving a raised outer margin about half an inch wide. To achieve better adhesion of the wax coating, the sunken area is covered with crisscross-hatching scored into the wood. The waxed surfaces would have been inscribed with a stylus and folded closed for protection. In order to keep the board tightly shut, there is evidence of a fastening mechanism consisting of a loop on one side and a hook on the other.

Sadly, none of the wax, and thus none of the text, has survived. We therefore do not know what was written on the diptych.2 The important discovery of the “book” proved not to be an isolated find: In the 1994 season, the excavators recovered a wooden leaf of a second diptych. Found resting against the shoulder of a storage vessel, the leaf measures nearly 3 by 5 inches and has provision for three hinges on one side.3

It is widely known that the traditional writing materials in the ancient Near East were clay tablets and later also scrolls, so it may come as a surprise to some readers to learn that waxed writing boards were also used by the scribes.

From cuneiform sources it had been suspected for some time that writing boards were widely used in temple and palace administration in Mesopotamia in the first millennium B.C. This was indeed confirmed archaeologically in 1953 by the sensational discovery at Nimrud (north Iraq) of a large number of ivory and wooden writing boards recovered from the bottom of a well in the Northwest Palace, dated to the late eighth century B.C.4

Equally, the existence of wooden writing material during the Hittite Empire in the second millennium B.C. has long been established from their archives, but no example has ever been found at any of the Hittite sites.

The discovery of the Uluburun diptych, which is contemporary with Hittite activities in the region, was therefore particularly welcome and generated great excitement among scholars. As a result of meticulous excavation methods, we are in possession of the earliest known example of this type of wooden “folding tablet” dated to the late 14th century B.C. The diptych has consequently been referred to as the oldest “book” in the world.

In both cases, at Nimrud as well as Uluburun, we owe the survival to the silt and water-logged conditions in which the writing boards were found. In most other archaeological contexts they are highly unlikely to have survived.

It was George Bass who first made the connection between the Uluburun diptych and the reference to a “folding tablet” made by Homer. In Book VI, line 169 of the Iliad, we learn that Bellerophon carried a “folding tablet” containing “baneful signs” to Lycia. This is the only reference to writing in Homer and, until the Uluburun discovery, scholars regarded this reference to a 033“folding tablet” as an anachronism, added to the text at a late date.

Where did the Uluburun diptych originate? The cargo on the Uluburun ship came from all over the eastern Mediterranean: Canaan, Cyprus, Syria, Mycenaean Greece and Egypt. Although we do not know the nationality of the ship, Bass and Pulak, among others, have suggested that it hailed from a port on the northern Levantine coast, possibly Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra) on the Mediterranean coast of Syria.

Apart from Syria, we have no contemporaneous evidence from any of these regions on the subject of writing on waxed wood.a In Mesopotamia, scattered references to writing boards first occur in Ur III texts (2112–2004 B.C.), but most of the evidence belongs to the Neo-Assyrian and Babylonian periods (c. 1000–500 B.C.), when waxed boards became increasingly popular. In the mid-second millennium B.C., writing boards are occasionally mentioned in Middle Assyrian and Babylonian texts, but the overwhelming evidence, for the period of the Uluburun wreck, comes from the archives of the Hittite capital Hattusa at

034

Hittite texts distinguish between wooden and clay writing materials, as well as between a scribe writing on clay (LÚDUB.SAR) and a scribe writing on wood (LÚ

On seals, the Hittites used a Hittite/Luwian hieroglyphic sign (see drawing of Hittite hieroglyphic seal) to refer to a scribe. Although the sign does not distinguish between scribe-on-wood and scribe-on-clay, it does appear to represent a two-leaved writing board opened out or a two-columned clay tablet.

Writing boards offered clear advantages over clay tablets. Although writing boards were expensive to produce, they were much lighter and less fragile than their clay counterparts. Most important of all, scribes could erase the writing board’s text—by smoothing over the wax—and write something else on it. But this also gave rise for concern: Texts could be altered, falsifying their original contents. Hence we find occasional references on clay tablets to wooden documents being “sealed.”

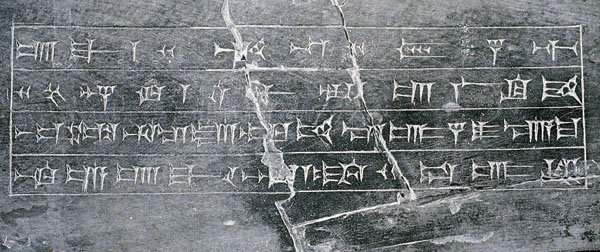

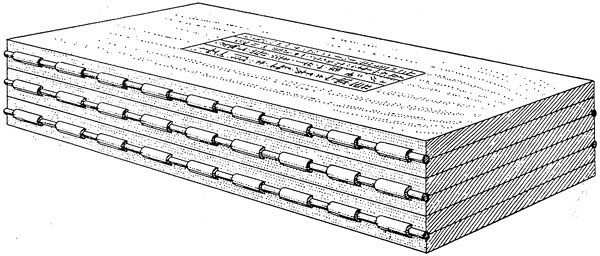

Most of our information about the appearance and manufacture of writing boards comes from Neo-Assyrian and Babylonian sources. A text from Nimrud (ND 2653), for instance, refers to the writing board’s individual “leaves” as daltu (“door”); the text indicates that such books contained as few as two leaves (a diptych) and as many as five leaves (a polyptych). But the number of leaves making up a “book” could be much larger. Among the 035writing boards found at Nimrud were 16 ivory boards 6 inches wide and 13 inches high. Although the leaves were no longer hinged together, there is no doubt that they formed part of a single set. As befits a “book,” the Nimrud polyptych has a “title” page consisting of four lines carved into the outer face of one of the leaves.

These ancient books were made from a variety of materials: wood, such as cypress, tamarisk and cedar, and occasionally ivory and even lapis lazuli. The Uluburun diptych has been identified as boxwood (in Akkadian, taskarinnu), frequently mentioned in Mesopotamian documents as a wood used in making furniture. The wooden boards found at Nimrud were of walnut.

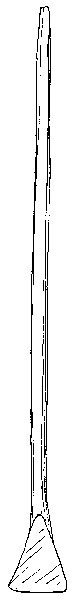

There is little doubt that writing boards in the Late Bronze Age were also coated with wax. A letter found at Ugarit, for example, refers to a “tablet of wax.” Although Hittite texts are silent on this matter, we can assume that they also covered their writing boards with wax—since they were familiar with bee-keeping, and beeswax was the kind of wax used on the boards. However, the most important indicator is the number of styluses of the tabulae ceratae type, specifically used for writing on wax, found at Hattusa. These styluses are usually made of bronze (occasionally of bone) with a pointed tip and a flattened, chisel-shaped end. The flattened end served to smooth the wax when erasing the script for correction or in order to re-use the writing surface.5

The hinges on the Uluburun and Nimrud writing boards allowed the boards to be opened and closed. The Nimrud boards could be folded alternately inwards and outwards, much like a Japanese screen. Before the Nimrud boards were flung into the well, the hinge pins had been forcibly removed, presumably by plunderers. This led the excavators to surmise that the pins were made of gold—though it is also possible that the hinges were leather thongs that have rotted away.

On the Uluburun writing board, three cylindrical ivory hinges were seated in concave grooves carved into the inner edge of the leaves. This allowed the boards to be opened out flat.

According to Mesopotamian sources, the writing board wax was mixed with

How were the writing boards used? Most of the evidence for the Late Bronze Age, to which the Uluburun ship is dated, is provided by Hittite sources from the archives at Hattusa. The examples 036discussed below illustrate the different spheres in which writing boards were used: as library copies, in palace and provincial administration, in the exchange of letters as well as official documentation.

From the religious texts it is apparent that writing boards were used as library copies which were consulted before and during religious ceremonies. Some wooden books were kept in the archives for long periods of time, even generations—as suggested by records stating that a text “was copied from an ancient wooden tablet” or that a ritual was performed according to the instructions “inscribed on an old writing board.” The Hittites placed great emphasis on executing a ritual or festival as laid down in the “instructions” of the (wooden) tablet. As we have seen, however, one disadvantage of the writing board is that the text can be erased and rewritten. King Mursili II (late 14th century B.C.) expressed concern that the ritual for the “Black goddess” had been “turned around,” meaning falsified, by the scribes-on-wood and the temple officials. So Mursili had new “instructions” inscribed on a “(clay) tablet,” which could not be altered.

One text, dealing with an enthronement festival, reads: “While the king pours libation daily, the scribes-on-wood hold a wooden tablet.” A birth ritual text refers to a “Festival of the Womb,” to be performed when a woman gives birth: “How they perform the festival, it is made on a wooden kurta tablet and it is (from) Kizzuwatnab and I do not know the festival orally, by heart.” As the text makes clear, long complicated rituals and festivals stretching over several days could not always be learned “by heart”—so writing boards were used as instruction manuals. On these occasions, they would have been much easier to handle than heavy clay tablets.

The ivory polyptych from Nimrud represents a true royal library copy—and a luxury version at that. According to the four-line inscription carved into the top cover of the book, we learn that the polyptych had been intended for the palace of Sargon II at Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad in Iraq):

Palace of Sargon, king of the world,

king of Assyria. The text series

(beginning) enuma Anu Enlil

he had written on an ivory writing

tablet and

deposited it in his palace at Dur-

Sharrukin.

Enuma Anu Enlil (“when [the gods] Anu and Enlil ”) is a well-known astrological omen series based on celestial observations; the text series is represented by numerous editions, written on clay tablets, in other Mesopotamian royal libraries.

One obvious function of waxed writing boards was for “book-keeping,” since they gave the writer the freedom to add, subtract and finally erase information that was no longer needed.

The use of wooden writing material in palace and provincial administration is widely attested. A series of inventory texts record items received as tribute, as well as imports from Syria, Cyprus, Egypt and Babylonia. From these sources, we know that writing boards were used for compiling lists of commodities and that at times they were attached to the goods they listed. Apparently, the scribe-on-wood was assigned the task of keeping inventories.

One inventory text refers to a basket “on lion feet”—containing linen from Amurru (north Syria) and Alashia (Cyprus)—said to be listed on a writing board. This text then records a tribute from an Anatolian 037town, stating that “the garments are noted on a writing board, thus (says) the queen: ‘When I put (the garments) into the seal-house, they shall make it into a tablet (of clay)’.” In this instance, the items were first listed on wooden boards; then the information was transferred to clay tablets, allowing the waxed boards to be reused.

There are also references in Hittite sources to “scribes-on-wood of the army/camp” and a reference to items listed “on the writing board of booty.” During military operations, the preparation of clay tablets would have been too difficult, so waxed boards were used instead. More than half a millennium later, in Neo-Assyrian times, writing boards were still being used to record the spoils of war. A relief from Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh (c. 640–615 B.C.) shows two scribes recording booty: One writes on a hinged diptych, while the other writes on a scroll.

That writing boards were used as letters—with the addressee simply smoothing over the wax and responding in kind—is suggested by a text from Ugarit. In this text, one scribe implores another to return his “tablet of wax.” If the other scribe wants a tablet, he can acquire one—but writing tablets should be returned to their owners. Very likely, writing boards were valued personal property and were marked as such. Although the markings on the inner margin of one side of the Ulubrun diptych have no epigraphic content, they could be the owner’s marks or they could identify the maker.

The Hittite records of court proceedings are a series of testimonies given by officials who are answering charges of embezzlement. They provide further examples of how writing boards were used. In one such text, the plaintiff is an unnamed queen, who charges a military official with dereliction of duty regarding royal property. The accused official states: “When they sent me to Babylon, the writing boards which I had concerning the horses and mules, I sealed them, but while I went to Babylon and until I returned again I did not seal them (again). The ‘receipt’ was not sealed (either).” The official is not confessing to stealing from the queen but to neglecting to seal the writing boards after the last entry. This is a recurring theme in Hittite texts; documents written on waxed tablets could be easily altered. To secure the boards, one had to seal them shut.

The Uluburun diptych provides valuable evidence about how the book was closed. It appears to have had a metal hook on one side and a loop on the other that would have fitted over the hook. But how was the book then sealed? At ancient Hattusa and at Tarsus, excavators have found large numbers of clay, cone-shaped bullae with seal impressions; these bullae frequently have string holes near the apex. It thus seems likely that wooden boards were tied with string and then sealed with a leather-hard lump of clay. Removing the string would have resulted in breaking the sealing, making an unauthorized interference of the document’s content obvious.

In the mid-13th century B.C., the Hittite queen Puduhepa, wife of Hattusili III, sent a letter to Egypt concerning her daughter’s forthcoming marriage to Pharaoh Ramesses II. In the letter, Puduhepa states that Hittite officials carried wooden documents with an inventory of the princess’s dowry, consisting of deportees and livestock. These items were listed on the writing boards dispatched to the Egyptian court.

The city of Ugarit in Syria was an important center of maritime trade in the Late Bronze Age and is obviously of particular interest regarding the Uluburun ship, since its cargo reflects the wide-ranging trade as documented in the Ras Shamra (Ugarit) texts. Indeed, it may well have been the Uluburun ship’s home port.

Apart from the letter referring to a “tablet of wax” discussed earlier, there is a text from the Ugarit archives mentioning a writing board. It is a letter sent by the king of Carchemish (north Syria) to the king of Ugarit in which the former complains about the lack of gifts sent to Hatti (their overlord) by the latter. It continues: “Now the writing board which they delivered to me, let them read (it) out before you.” What this seems to say is that the writing board sent from Hatti, which contained the itemized list of the requested gifts, was brought for approval to the king of Carchemish before being sent to Ugarit, where it was to be read out to the king of Ugarit. The content of this letter clearly reflects the political situation in the 14th and 13th century B.C., when kings of Carchemish acted as Hittite viceroys and mediators in Syrian affairs, a region largely under Hittite autonomy.

What conclusions can we draw from the writing boards recovered from the Uluburun shipwreck? We have seen that writing boards served as documentation (mainly in the form of lists) for the exchange of royal gifts, as means of exchanging messages and as inventory lists that accompanied goods and their envoys on foreign journeys.

Hittite inventory texts frequently mention the nature of containers in which 058items were stored and possibly also transported. They occasionally note that wooden documentation was missing from a shipment or that certain items were not marked on the writing board. It was probably common practice to attach a wooden writing board to a valuable shipment as a kind of label recording the shipment’s contents. This “label” was then either placed inside the container or attached to it in some way. This is probably how the Uluburun diptychs were used. Both were found associated with large pithoi containing shipments of goods. So the Uluburun waxed writing boards may well have listed the contents of the containers. At the same time, the possibility that the diptychs contained letters, “bills of lading” or the records of individual officials on board ship cannot, of course, be excluded.

Although post-dating the Uluburun writing boards by some 600 years, the following passage from a Neo-Assyrian letter fits the context of the Uluburun find remarkably well: “The goods of mUmbakidini which m

In 1986, two years into the excavation of the Uluburun shipwreck, the team from the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, led by George F. Bass and Cemal Pulak, made one of its most remarkable discoveries. While sifting through the sediment of a large pithos that contained the remains of pomegranates, bronze implements and some ballast stones, 032they found the world’s oldest book!1 The book—a small, hinged writing board from the late second millennium B.C.—was reassembled from 25 fragments by Robert Payton at the Museum of Underwater Archaeology at Bodrum, Turkey. It is a diptych, consisting of two rectangular wooden […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

In Late Bronze Age Egypt, writing boards were covered with stucco and fabric and written on with ink. Only in Greco-Roman times were wax-covered boards introduced into Egypt. The literacy of other regions such as Canaan, the west coast of Anatolia (Arzawa) and Cyprus (Alashia) is evident from the Amarna Letters, the diplomatic correspondence between Near Eastern rulers and the Egyptian court in the 14th century B.C., but their archives have invariably not been located. As for Mycenaean Greece and Crete, Linear B tablets make no mention of wooden writing material. But a number of clay sealings have been found, which may have been used to seal more perishable writing materials.

Endnotes

George F. Bass, “A Bronze Age Shipwreck at Ulu Burun (

For full bibliographic details and text references of this article, see the following articles in Anatolian Studies 41 (1991), Journal of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara: Robert Payton, “The Ulu Burun writing board set”; Peter Warnock and Michael Pendleton, “The wood of the Ulu Burun diptych”; and Dorit Symington, “Late Bronze Age writing boards and their uses: textual evidence from Anatolia and Syria.”

Cemal Pulak, “RES MARITIMAE” in S. Swiny et al, eds., Cyprus and the Eastern Mediterranean from Prehistory to Late Antiquity, CAARI Monograph Series, vol. 1 (1997), p. 252f.

D.J. Wiseman, “Assyrian Writing Boards,” Iraq 17 (1955), published by the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, pp. 3ff.; M.E.L. Mallowan, Nimrud and its Remains, vol. 1 (London, 1966), pp. 149ff.